List of Abbreviations

CST Central Services Team

DAERA Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

DEFRA Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

DoE Department of the Environment

DoJ Department of Justice

EU European Union

ECU Environmental Crime Unit

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

FI Financial Investigators

IPRI Industrial Pollution and Radiochemical Inspectorate

IRIS Incident Recording Information System

MRF Materials Recycling Facility

NCA National Crime Agency

NED Natural Environment Division

NI Northern Ireland

NIEA Northern Ireland Environment Agency

NS Natural Science

OEP Office of Environmental Protection

ORP Operational Review Programme

PoCA Proceeds of Crime Act

PCBs Polychlorinated Biphenyls

PCG Parent Company Guarantee

PIMS Pollution Incident Management System

PPC Pollution Prevention and Control

PPS Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland

RoI The Republic of Ireland

RU Regulation Unit

WMU Waste Management Unit

Glossary of Terms

Commercial waste Waste arising from premises that are used wholly or mainly for trade, business, sport, recreation or entertainment, excluding household and industrial waste.

Construction and demolition waste Arising from the construction, repair, maintenance and demolition of buildings and structures. It mostly includes brick, concrete, hardcore, subsoil and topsoil, but it can also include quantities of timber, metal and plastics.

Contaminated land regime This regime supports the ‘polluter pays’ principle and provides a legal framework for dealing with historic contamination. It is fully retrospective in action. It aims to provide a system for the identification and remediation of land where contamination is causing unacceptable risks to human health, the natural environment and/or property. The Local Councils will be the primary regulators for this regime with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (the Department) having defined regulatory roles and responsibilities.

Exempt waste Waste that does not require NIEA registration:

- waste that is baled, compacted, shredded or pulverised at its place of production.

- burial of sanitary waste from the use of a sanitary convenience on the premises.

- the keeping or deposit of waste from peatworking.

- deposit of borehole or excavated waste.

- the burial of a domestic pet in the garden of a domestic property where the pet lived.

- the storage or deposit of waste samples to be tested or analysed.

- storage of waste medicines at a pharmacy or storage of waste of a medical, nursing or veterinary practice.

- temporary storage of waste, pending its collection at the place where it is produced.

- transitional arrangements for the treatment, keeping or disposal at any premises of scrap metal or waste motor vehicles that are to be dismantled pending the issue of a licence.

Groundwater Groundwater is all water found underground in the cracks and spaces in soil, sand and rock.

Hazardous waste Hazardous waste is waste that is harmful to humans and/or the environment due to its properties or the substances it contains. Hazardous waste streams include:

- asbestos waste

- fluorescent tubes

- clinical waste

- chemicals

- used oil filters

- brake fluid

- batteries (lead acid, Ni-Cd and mercury)

- some printer toner cartridges

- waste paint and thinners

- some catalytic converters/diesel particulate filters

- Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)

PCBs are recognised as a threat to the environment due to their toxicity, persistence and tendency to build up in the bodies of animals.

Household waste Waste generated from domestic properties including waste from caravans, residential homes and premises forming part of an educational establishment or part of a hospital or nursing home.

Industrial waste Any waste – whether liquid, solid or gas – that is a byproduct of manufacturing or industrial processes.

Landfill sites An area of land in which waste is deposited. They are carefully designed structures built into the ground so that waste is kept separate from the surrounding environment.

Leachate A contaminated liquid that is generated from water draining or “leaching” through a solid waste disposal site.

Mills Report In June 2013 the then Department of the Environment (DoE) Minister commissioned an independent report from Mr Chris Mills, the former Director of the Welsh Environment Agency, into waste disposal at the Mobuoy site and included the lessons to be learned for future regulation of the waste industry in Northern Ireland.

Polluter pays principle Where the person/organisation who is responsible for producing pollution should be responsible for paying for the damage done to the natural environment. This principle has also been used to put the costs of pollution prevention on the polluter.

Pollution prevention This is an environmental permit for a plant or installation that emits and control permit pollutants to the air.

Recovery Any operation in which the main goal is that the waste serves a useful purpose by replacing other material that would otherwise have been used to fulfil a particular function.

Recycling The process by which waste products are broken down to their basic materials, and remade into new products; this should mean the use of less virgin raw materials.

Surface water Surface water is water that flows or rests on land and is open to the atmosphere, including rivers, lakes, loughs, streams, reservoirs and canals.

Waste management A waste management licence is required to authorise the deposit, treating, licence keeping or disposal of controlled waste on any land or the treatment or disposal of controlled waste by means of mobile plant.

Waste carrier A person who collects or carries waste. If a person transports other people’s waste or their own construction and demolition waste, they are required to be registered with the NIEA.

Waste transfer note A document that details the transfer of waste from one person to another. Every load of waste that is passed from one person/company to another has to be covered by a waste transfer note. The only exception is when household waste is received directly from the householder who produced it, but a waste transfer note is then required when it is passed on to someone else. They ensure that there is a clear audit trail from when the waste is produced until it is disposed of.

Key Facts

At least 300,000 tonnes - Total waste deposited illegally in Northern Ireland each year (according to a 2015 estimate)

£34 million - Estimated annual cost of waste crime in Northern Ireland

2 out of 36 - Number of criminal cases in the last five years resulting in remediation taken by the defendant to restore the environment

£17 million - Total costs evaded from illegally disposed waste in legal proceedings since 2019

£1 million - Total value of court fines imposed in relation to waste crime in these proceedings

Around £3,500 - Costs evaded by illegally dumping a volume of standard waste equating to a bin lorry load

Executive Summary

Background and introduction

1. Waste crime is a broad term that includes all aspects of illegal waste disposal. It ranges from an individual littering on the street to large-scale commercial fly-tipping and the operation of illegal waste disposal sites. It includes the collection, storage, transportation, processing, export, or disposal of waste without a licence.

2. All activities involving the treatment, movement, storage, or disposal of waste are required to be authorised by the Northern Ireland Environment Agency (the NIEA), an agency of the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (the Department).

3. In February 2012, the NIEA uncovered an illegal dump at Mobuoy, County Londonderry. It contains an estimated 635,000 tonnes of illegally deposited waste. It is one of the largest illegal dumps in Europe. Historically, the site was subject to waste depositing, some of which dates back decades. It is estimated that approximately 1.6 million tonnes of waste are currently at the site. Part of the site was an NIEA regulated site, which included a landfill facility and a materials recycling facility (MRF), with a long history of repeated non-compliance for various reasons. However, there was also a wholly illegal waste dump on the site. The clean-up costs for this dump are currently estimated to fall between £17 million and £700 million and it is expected that costs will largely fall to the public sector to fund.

4. In 2013, the then Minister for the Environment commissioned a review of waste disposal at the Mobuoy site, to include lessons to be learned for the future regulation of the waste industry in Northern Ireland (NI). The subsequent report - the Mills Report - included 14 key recommendations for improvement and these are included at Appendix 1. Although it is now 12 years on from the publication of the report, during the course of our review we identified a number of instances where the issues highlighted by Mills are still prevalent. We have referenced these at the appropriate points within our report.

Illegal dumping of waste has a significant cost to the public purse

5. In 2015, the Strategic Investment Board reported that at least 300,000 tonnes of waste are being deposited illegally in NI each year. At that time the NIEA estimated that one-third of illegal waste deposited in NI was from outside our borders while the rest was generated locally. At the present time, more up-to-date figures are not available.

6. In 2021, the National Crime Survey estimated that waste crime in England costs around £1 billion a year, through evaded tax, environmental and social harm and lost legitimate business. No comparative figure is available for NI, but based on relative population size, the costs in NI are likely to be around £34 million a year.

The NIEA’s inspection work is not always targeted at areas of highest environmental risk

7. Those involved in the waste management industry are required to operate under a form of authorisation issued by the NIEA – this encompasses licences and permits. In 2023, there were 5,815 authorisations in place for a range of activities in NI.

8. The NIEA is required to operate a full cost recovery model for its waste regulatory activity and much of this is focused on waste management sites where the bulk of waste-related fees are generated. The NIEA told us that the resources are not available to enable this activity to always adequately target the areas of greatest environmental risk.

9. The level and number of inspections carried out should be dependent on the level of risk identified. However, the NIEA has confirmed that there have been no inspections conducted in the last two years where either site inputs are matched to outputs or where waste materials are verified on site. The NIEA has advised that these inspections have been paused since 2023 as they are not a statutory requirement and resource constraints have required the Agency to prioritise delivery of its statutory obligations. Detailed inspections involving the checking of Waste Transfer Notes are especially important for facilities that are not the final destination of the waste. They enable waste to be tracked to ensure that it does not end up in an illegal dump. Furthermore, the number of planned inspection visits has significantly reduced in recent years for each risk level.

Some waste management activities do not require a permit or licence

10. Waste management activities such as small-scale waste storage and waste recovery operations are considered to pose a low risk of harm to the environment and to human health, and thus they are allocated waste exemptions and do not require a permit or license, but in most cases these still need to be registered with the NIEA.

11. Waste activities covered under exemptions are deemed to be lower risk and consequently they have lesser regulatory controls. The fit and proper person test does not legislatively apply to exemptions, and while the NIEA conducts criminal conviction checks on exemption applicants, we consider that the lack of a fit and proper person test could lead to the system being abused. Exempt sites are not charged an annual fee and there is no programme of site inspections. Compliance monitoring by the NIEA of waste exemptions is crucial to obtain the necessary assurances that such waste is not being dumped illegally, and the sites are not a pollution risk.

The NIEA does not have a detailed knowledge of the nature, source and volume of output of each waste stream it is responsible for regulating

12. Having comprehensive accurate and timely waste data is a key component in making any assessment of local waste infrastructure needs. In both our 2005 report on NI’s Waste Management Strategy and our 2024 Review of Waste Management in NI report, we identified that there are no accurate figures for the extent or classification of approximately 87 per cent of waste generated in NI. This makes the management of waste difficult and may provide increased opportunity for criminal activity in the sector.

13. The UK government is currently in the process of introducing a UK-wide digital waste tracking system and the Department is working with the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) towards a launch date of April 2026 for waste tracking in NI.

Legislation to modernise the NIEA’s regulation and enforcement capabilities has not been introduced

14. The Environmental Better Regulation Act, which came into effect in April 2016, was intended to act as the starting point for the modernisation of waste regulation. This could lead to a more joined up regulatory system and allow the Department to review, repeal, rewrite and add safeguards to powers of entry. It also requires the creation of a code of practice for powers of entry. These additional powers would assist with the prevention and detection of waste crime. However, over nine years later, the regulations that would give effect to that legislation and facilitate the streamlining of waste licensing, as well as the move to more effective regulation and enforcement, have not yet been introduced.

Northern Ireland is the only region in the United Kingdom without a contaminated land regime

15. NI does not have a contaminated land regime to address environmental damage, even where significant pollution is discovered. While Part 3 of the Waste and Contaminated Land (NI) Order 1997 contains the main legal provision to allow one to be put in place, the regulation is not in force. Where contamination is causing unacceptable risks to human health, the natural environment and/or property, such a regime would provide a mechanism to:

- identify and deal with potentially serious problems arising from pollution/contamination of land; and

- establish who should pay for remediation.

16. NI is the only region of the UK where this type of regime is not in place. The 1997 Order supports the ‘Polluter Pays’ principle and provides a legal framework for dealing with historic contamination such as illegal waste sites. Despite previous recommendations from both the Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG) and the Public Accounts Committee, this important legislation has still not been enacted. The Department has stated that it has legislation that it can use to proceed with remediation but, at the present time, this has not yet been used. The Department has advised us that using any of these legislative tools creates significant financial risk and requires infrastructure not already available and additional project management resources.

Opportunities for tracking waste are being missed by the NIEA

17. There is a system in place to facilitate the tracking and control of waste, but it is not utilised to its full potential by the NIEA. Individual waste transfers are recorded by creating a Waste Transfer Note and/or a Consignment Note (for hazardous waste). International waste imports and exports also require either Annex IB (notifiable waste) movement forms or Annex VII (green list waste) forms to accompany each waste movement. These are documents that detail the transfer of waste from one person to another. Every load of waste that is received or passed on to others is required to be covered by one of these notes.

18. Waste Transfer Notes are not submitted to the NIEA but are retained by the issuer and may be subject to inspection. Despite inspections having the potential to identify waste crime, the NIEA informed us that while they do sample Waste Transfer Notes to ensure that they have been fully completed, they do not hold records of how often this has happened in the last five years.

19. Consignment Notes (of which there are approximately 28,000 each year), must be submitted to the NIEA. The notes must be signed by both parties i.e. the person that is passing on the waste and the person receiving it, and must contain certain prescribed information, including a written description of the waste and any information required for subsequent holders to avoid mismanaging the waste. The NIEA informed us that these documents are reviewed to ensure they are completed in compliance with legislation, although the onus is on the carrier (technically known as the consignor) to inform the NIEA of any hazardous waste movements in NI three days prior to the movement taking place. The prior notice provides the NIEA with an opportunity to contact the carrier to prevent potentially non-compliant waste movements. The recipient of the waste also has a duty to inform the NIEA of receipt of this waste, enabling the NIEA to assess whether the waste has been deposited in a suitable location. The NIEA has informed us that there is a significant backlog in this work, thereby undermining the effectiveness of this important control. The information from Consignment Notes is recorded on a central database.

Routine inspections are not carried out on registered carriers

20. To transport any type of waste, a person or business must be registered with the NIEA. Once registered, the person or business can carry any type of waste, including commercial, industrial, household and even hazardous waste. The NIEA told us that the legislation places no restriction on the number, size or type of vehicles covered by the registration. Furthermore, the registration charge for carriers is a single fixed amount, rather than being varied to reflect the level or type of waste transported. The current carrier registration fee provides opportunities for those seeking to exploit the system.

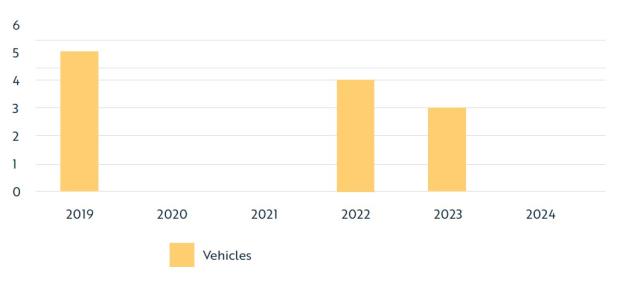

21. Presently, there is no routine inspection regime for registered carriers, but the NIEA told us that offence checks are conducted at initial registration and renewal. The NIEA also carries out periodic stop and search operations in combination with the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) and His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC), but the extent of these is limited, with only one such operation being conducted in 2024. Where unregistered operators are identified, enforcement action can be taken.

Profits from illegal dumping far outweigh the sanctions

22. To prevent waste crime, a range of compliance and enforcement measures must be in place. One such measure should be that perpetrators of illegal activity face a punishment that dissuades them from committing the crime in the first place or from re-offending. The Mills Report identified that penalties for waste crime were lower in NI than in the rest of the UK and was critical of the fact that that sentencing was too lenient to provide an effective deterrent.

23. Between 2019 and 2024, there were 52 criminal convictions in relation to waste crime in NI. These have resulted in fines of almost £100,000 and Confiscation Orders of almost £900,000. However, these amounts are significantly less than the £17.2 million estimated costs that operators should have paid for legally disposing of the waste involved in these proceedings.

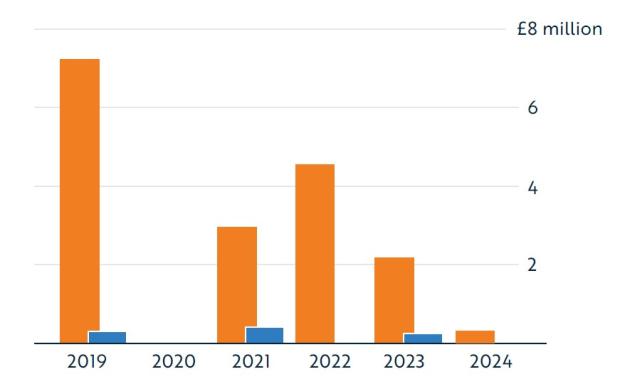

Figure 1: The costs of waste disposal significantly exceed the value of fines and confiscation orders awarded in relation to environmental crime

Between 2019 and 2024 the estimated cost of illegal waste disposal was £17.2 million, with just under £1 million of fines and confiscation orders awarded over the same period.

Source: NIEA

Only two of the 36 legal cases have involved the reinstatement of the environment

24. There are a range of actions that the Environmental Crime Unit (the ECU) can take to address non-compliance, depending on the severity, complexity and nature of the case. The NIEA has advised that the ECU seeks to take enforcement action that is proportionate to the significance of the offence, influenced by the level and type of offending, the harm caused (including the impact on communities), the level of financial benefit arising, or where non-compliance with remedial notices has taken place. For minor offences, the ECU will seek remediation, give advice and guidance, issue warning letters, or issue fixed penalty notices. For more serious offences, the ECU may submit a report to the Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland (PPS) for consideration of prosecution. In the past five years, the ECU has taken forward 36 criminal prosecutions, however, in only two of these has the reinstatement of the environment by the defendant been an outcome. We were advised by the NIEA that, following conclusion of the relevant court case, illegal sites are no longer monitored on an ongoing basis to assess the continuing environmental impact of the site. The Mills Report also referenced this issue.

Waste management licences are rarely revoked in Northern Ireland

25. A waste management licence can be revoked or suspended where there is a risk of pollution, harm to human health, or a detriment to the amenities of the area in which the facility is sited. It can also be revoked or suspended where the NIEA considers that the licensee has ceased to be a fit and proper person as a result of being convicted of a prescribed offence. The NIEA has advised that 14 licences have been revoked in NI in the past ten years.

There have been lengthy delays in repatriating waste originating in the Republic of Ireland

26. Under a framework agreed in June 2009, the full cost of disposing of illegal waste that originated in the Republic of Ireland (the RoI) is met by the Irish Government, together with 80 per cent of the costs of removing the waste from NI. However, repatriation of such waste is not happening on a timely basis due to the lack of landfill capacity in the RoI, together with a lack of funding available to cover the cost of excavation and transporting waste back across the border. In one such case, which came to light in 2004, approximately 270,000 tonnes of waste from the RoI had been dumped in 17 illegal sites in NI. Some 20 years later, almost half of the waste has still not been removed. The Department advised that the UK Government, via DEFRA, has some responsibility for the resolution of this issue and noted that there are international relations considerations. The Department told us that periods when the NI Assembly was not in place also presented a barrier to earlier resolution as North/South ministerial negotiations could not take place. However, the Department highlights that progress is now being made and its officials are actively engaged with the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications (DECC) in RoI on agreeing a way forward.

The ‘fit and proper person’ test is not effective in regulating waste and stopping waste crime

27. The NIEA complements its system of compliance inspections with a ‘fit and proper person’ test, which aims to ensure that a person responsible for operating waste sites is a fit and proper person to hold a waste management licence. The test has three elements; prescribed offences, technical competence and financial assurance. Since 2011, no applications have been refused, nor have any licences been revoked for failure to meet the technical competence element of this test.

28. The financial assurance component requires the licence holder to provide evidence that they have adequate funding available to address the potential environmental and human health implications of the waste activity they are undertaking.

29. An internal audit review of the financial assurance provisions in January 2024 noted that there were significant gaps in the information provided by waste operators. This is a concern since it increases the risk that the public sector might have to incur significant clean-up costs in the event that one is required. The NIEA has stated that it is currently unable to meet the target set out in its policy, which requires the financial assurances provided by all waste operators to be reviewed on an annual basis.

30. There are also potential risks around taking assurance from Parent Company Guarantees (PCGs). These involve highly complex legal contracts, and the internal audit team stated that the NIEA has neither the trained staff nor sufficiently developed procedures to ensure that the financial obligations could be legally enforced.

Poor data collection and management information is undermining the NIEA’s ability to regulate the waste management industry

31. The NIEA, as regulator, needs reliable information to identify significant risks to compliance; determine strategies to address those risks; assess the effectiveness of its activities; and demonstrate how well it is performing. Poor data collection and management information is undermining the NIEA’s ability to regulate the waste management industry as effectively as it could. The NIEA told us that much of the information it holds is recorded on individual files but not held centrally. As a result, much of the information collected is neither readily accessible to the NIEA nor in a format that can be easily analysed.

32. Currently the NIEA uses three different computer systems for incident reporting, depending on the nature of the incident. The systems do not interface with one another, which can result in the double handling of the information by separate teams within the organisation. This is inefficient and could lead to problems where information is not communicated between teams.

33. Two of the systems are at the end of their useful lives and were due to be replaced over five years ago. However, plans for their replacement do not involve a fully integrated system for incident reporting across the various sections of the NIEA. This would bring the following benefits:

- a reduction in administration;

- a single point of entry for all information;

- the effective sharing of intelligence across sites; and

- an evidence base, to help target resources in the timely review and monitoring of potentially illegal/polluting sites.

The NIEA lacks some of the skills to effectively regulate the waste sector

34. At the time of writing this report, the NIEA told us that it struggles to recruit and retain specialist skills in a number of key areas and that these skill shortages can impact on the quality of NIEA enforcement activity, including the number of confiscation order applications being brought before the courts.

35. Potential options such as recruiting specialist staff jointly with other regional environment agencies have not been explored by the NIEA. The importance of having specialist skills to facilitate waste regulation was previously drawn out in the Mills Report.

Conclusion

36. The current approach to regulating waste in NI requires improvement. The inspection regime doesn’t adequately identify instances of crime or sufficiently discourage criminality. Legal enforcement activities, even when successful, rarely result in the polluter remediating the damage caused and financial recoveries are only a fraction of the costs of dealing with the waste legally. As a result, damage is being caused to the environment and the liability for remediation costs often falls to the public purse.

37. We conclude that the NIEA’s expenditure on regulating waste cannot be considered to be achieving best value for money. The deficiencies in the current arrangements also put at risk delivery of the NIEA’s obligations to protect the environment.

38. The recommendations in our report outline a series of measures that the NIEA in conjunction with the Department could take to assist in their efforts to fight waste crime and thereby afford further protection to NI’s environment.

Recommendations

Recommendation

The NIEA should carry out a review of its inspection regime, to incorporate:

- the adequacy and frequency of compliance inspections, including:

- the review of transfer and consignment notes to identify waste that is not being disposed of legally;

- risk-based inspections for exempt sites; and

- joint waste and water inspections;

- the financial contribution of fees and charges towards the cost of the inspection regime; and

- the availability of robust and timely data and intelligence to enable resources to be effectively targeted at areas of most significant environmental risk.

Recommendation

The NIEA should review the requirements in place for operators to be registered to trade legally in the waste sector. In particular, the NIEA should consider the requirements and standards for those wishing to transport hazardous waste or waste in significant volumes, as well as the adequacy of the current system for obtaining financial assurances on waste operators. This work should include ensuring that the required financial assurances are obtained for all waste operators on an annual basis as specified in the organisational policy.

Recommendation

The NIEA should reassess its remediation arrangements. We recommend the introduction of updated processes to regularly review identified waste crime sites following conclusion of court cases, with prompt remedial action as appropriate to ensure that the waste is not having an ongoing detrimental effect on the environment. A priority issue for the Department should be reaching agreement with the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications in RoI regarding the illegal waste that originated in RoI in 2004. It should ensure that effective action is taken to address the longstanding issues presented by this illegal waste and thus ensure that the remaining waste can be remediated within a defined timeframe.

Recommendation

The Department should propose a timeline for introducing the arrangements to give effect to the Environmental Better Regulation Act (NI) 2016 and the Waste and Contaminated Land (NI) Order 1997. The former legislation provides additional powers to assist the NIEA in combating waste crime, whilst the latter could provide a means of dealing with legacy sites impacted by contamination, particularly in instances where no-one can be made amenable.

Recommendation

The NIEA should review the methods and accessibility for members of the public to report their concerns about potential waste crime, including promotion of these in conjunction with the arrangements for reporting water pollution incidents. This would help ensure that waste crime and water pollution are given equal prominence in the minds of the public as important issues in the fight to protect the environment.

Recommendation

The NIEA should set a timeline for replacing its incident reporting IT systems across its divisions – waste, water and marine. When doing so, the NIEA should explore the merits of a fully integrated system to address the shortcomings in the current systems.

Recommendation

The NIEA should explore potential solutions to the current recruitment and retention challenges and establish a workforce strategy and corresponding recruitment plan to address those challenges. This should incorporate the potential for accessing specialist skills in conjunction with other regional environment agencies.

Part One: Background and introduction

What is waste crime?

1.1 Northern Ireland produces approximately 7.7 million tonnes of waste each year. Waste comes in a range of forms, including: household, commercial and industrial waste; construction, demolition and excavation waste; hazardous waste; agricultural waste; and wastewater. Most of the waste produced in Northern Ireland (NI) is disposed of legally. Waste crime is a broad term that includes all aspects of illegal waste disposal. It ranges from an individual littering on the street to large-scale commercial fly-tipping and the operation of illegal waste disposal sites. It includes the collection, storage, transportation, processing, export, or disposal of waste without a licence.

1.2 Waste crime generally falls into one of six categories:

- illegal waste sites (which may operate for a short or a prolonged period);

- illegal burning of waste;

- fly-tipping;

- misclassification and fraud;

- intentional breaches of permits, licences and exemption conditions; and

- illegal exports of waste.

1.3 Waste that is not managed legitimately can pollute the land, the waters and the air that we breathe, potentially harming both human health and the environment. For example, rainwater can mix with the waste to form a toxic leachate (run off from a waste site), which can enter water courses, causing damage to habitats and contaminating sources of drinking water. Unlicensed activity results in a direct loss to the public purse through lost licence fee income and landfill tax. It comes largely at the expense of the taxpayer as responsibility for subsequent clean-up costs often falls to the relevant public bodies. It also leads to reduced revenue and profits for legitimate waste operators who cannot compete with the substantially lower costs incurred by those operating outside of the law.

1.4 In 2013, the then Minister for the Environment commissioned a review of waste disposal at the Mobuoy site, to include lessons to be learned for the future regulation of the waste industry in NI. The subsequent report – the Mills Report – included 14 key recommendations for improvement that are included at Appendix 1. The Northern Ireland Environment Agency (the NIEA) stated that they have implemented 13 of these recommendations – one was outside their remit. Although it is now 12 years on from the publication of the report, our review has identified a number of instances where the issues highlighted by Mills are still prevalent. We have referenced these at the appropriate points within our report.

1.5 In 2021, the National Crime Survey estimated that waste crime in England costs around £1 billion a year, through evaded tax, environmental and social harm and lost legitimate business. No comparative figure is available for NI, but based on relative population, then the costs are likely to be around £34 million a year.

1.6 Our 2024 Waste Management in NI report noted that NI’s last Waste Strategy was published in 2013 and, whilst it set a framework for managing waste until 2020, it did not include a structure for addressing waste crime. The closure report on the 2013 strategy was published in 2022, and while the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (the Department) advised us that a new Waste Strategy would be published before the end of 2024, this has not yet taken place, and it is not clear at the present time whether it will include a framework for tackling waste crime.

Waste responsibilities in Northern Ireland

1.7 All activities involving the treatment, movement, storage, or disposal of waste are required to be authorised by the NIEA, an agency of the Department. In addition, the NIEA is responsible for waste clean-up costs where it involves hazardous waste on public lands and/or where the volume of waste exceeds the equivalent of one bin lorry load or 20 cubic metres, (anything under the equivalent of one bin lorry load is the responsibility of the relevant Council). Where there is an identifiable landowner/controller, the responsibility for remediation sits with them. This can lead to landowners having to pay (sometimes repeatedly) for clearing waste that has been illegally dumped on their land. The NIEA will only remediate in these circumstances if there is a real and immediate threat to environmental and/or human health. This can result in landowners having to pay to clean up other people’s illegally dumped waste.

1.8 The NIEA’s Regulation Unit grants exemptions, licences and permits, sets conditions on licensing activities, monitors sites and undertakes monitoring to ensure compliance with licence conditions. The NIEA is also responsible via its Environmental Crime Unit (the ECU) for investigating and prosecuting serious and persistent environmental crime.

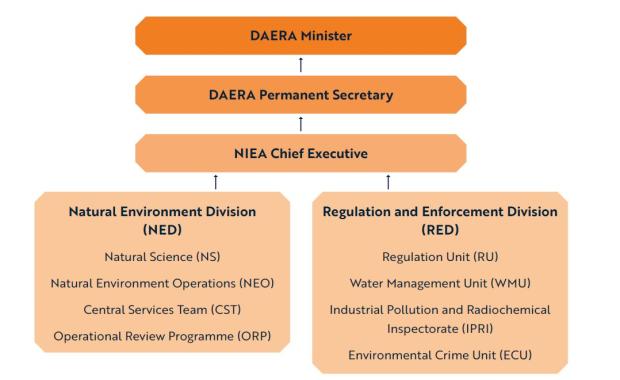

1.9 Within central government, the Department has overall responsibility and accountability for the regulation of waste. The lines of responsibility and organisational arrangements are shown at Figure 2.

Figure 2: Central government waste organisation structure

Source: NIEA

Illegal dumping of waste has a significant cost to the public purse

1.10 The drive to reduce the amount of waste sent to landfill and the rapid rise in the rate of landfill tax has increased the financial incentives for those who are willing to dispose of waste illegally. In 2015, the Strategic Investment Board reported that at least 300,000 tonnes of waste were being deposited illegally each year in NI. At that time, the NIEA estimated that one-third of illegal waste deposited in NI was from outside our borders while the rest was generated locally. At the present time, more up-to-date figures are not available.

1.11 The costs evaded by those illegally disposing of a volume of waste equivalent to a bin lorry load are approximately £3,555.60 – see Figure 3. The majority of this money is tax foregone to the UK government and, as a knock-on effect of the illegal disposal, there are often clean-up costs to be met from the public purse. Profits made by the perpetrators of waste crime are therefore largely at the expense of the public sector.

Figure 3: Costs evaded by the illegal dumping of the equivalent of one bin lorry load of waste in Northern Ireland

Source: NIEA

1.12 The Mills Report (Appendix 1 – Key recommendation 1) recommended that the lead department on waste – at the time this was the Department of the Environment but is now DAERA - should include combatting waste crime as a corporate priority, due to the seriousness and cost to the public purse of these illegal activities. While this was included as a corporate priority following the completion of the report, this is no longer the case.

Scope of this report

1.13 This report examines the NIEA’s current approach to regulation of the waste industry and considers how it tackles waste crime. Part Two reviews the arrangements for licensing and compliance monitoring; Part Three examines enforcement activities and outcomes; Part Four considers the NIEA’s use of management information to help tackle waste crime, and Appendix 1 sets out for reference purposes the Mills Report recommendations. Throughout this report, we have highlighted areas where the evidence suggests that elements of the Mills Report recommendations are still prevalent.

Audit methodology

1.14 We used a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to gather evidence for this report, including;

- Discussions with key staff at the NIEA and the Department;

- Review of documentation; and

- Use of case studies where appropriate.

Part Two: Licensing and compliance monitoring

The NIEA is responsible for authorising all waste management activity in Northern Ireland

2.1 Those involved in the waste management industry are required to operate under a form of authorisation issued by the NIEA – this encompasses all licences and permits. A waste management licence (WML) is required to authorise the deposit, treating, keeping or disposal of controlled waste on any land or the treatment or disposal of controlled waste by means of mobile plant. A pollution prevention and control (PPC) permit is an environmental permit required where a plant or installation emits pollutants into the air. In 2023, there were 5,815 authorisations in place for a range of activities in NI – see Figure 4. WMLs and PPC permits are issued without an end date and are generally not reviewed unless, for example, the operator applies to vary the licence or permit. Waste exemptions are issued for either one year or three years depending on the type of exemption, after which they expire unless a renewed application is received and granted.

2.2 The NIEA’s waste regulating activities operate under a full cost recovery model that requires it to fully recover the costs of its work, including inspections, from licence and permit application fees and annual charges. In 2024-25, the NIEA generated £4.67 million in income in relation to waste regulation.

Figure 4: Authorised activity

| Activity | Number of authorisations |

|---|---|

| Register of Carrier Licence | 4,977 |

| Waste Exemption | 389 |

| Waste Management Licence | 361 |

| Pollution Prevention and Control Permit | 88 |

| Total | 5,815 |

Source: NIEA

Waste management licences or pollution prevention and control permits can only be revoked in specified circumstances

2.3 A WML or PPC permit can be revoked or suspended where there is a risk of pollution, harm to human health or a detriment to the amenities of the area in which the facility is sited. It can also be revoked or suspended where the NIEA considers that the licensee has ceased to be a fit and proper person as a result of being convicted of a prescribed offence. In the last ten years there have been 14 WMLs or PPC permits revoked by the NIEA.

2.4 Operators who appeal a revocation or suspension can continue to operate until the appeal is determined. A review of the Planning Appeals Commission website indicates that there have been 11 appeals in the last ten years. All of these appeals were successful and the revocation or suspension overturned.

The Better Regulation Act is not enacted eight years after coming into effect

2.5 The Executive’s 2012 Economic Strategy Action Plan committed the then Department of the Environment to produce primary legislation to improve environmental regulations, cut red tape and reduce the regulatory burden on business by 2015. The Environmental Better Regulation Act (NI) 2016, which came into effect in April 2016 was intended to act as the starting point for the modernisation of waste regulation, by integrating five separate regimes into one Environmental Permitting system. This could lead to a more joined up regulatory system and provide enhanced powers, including the power of entry to assist with the prevention and detection of waste crime. However, nine years later, the regulations that would give effect to that legislation and facilitate the streamlining of waste licensing, as well as the move to more effective regulation and enforcement, have not been introduced.

Northern Ireland is the only region in the United Kingdom without a contaminated land regime

2.6 In our 2011 report on The Transfer of Former Military and Security Sites to the Northern Ireland Executive, we identified that NI does not have a contaminated land regime to assist the NIEA in addressing environmental damage. While Part 3 of the Waste and Contaminated Land (NI) Order 1997 contains the main legal provision to allow one to be put in place, the regulation is not in force. It would provide a way of:

- identifying and dealing with potentially serious problems arising from pollution/contamination of land; and

- establishing who should pay for remediation.

where contamination is causing unacceptable risks to human health, the natural environment and/or property.

2.7 NI is the only region of the UK where this type of regime is not in place. England has had a contaminated land regime since 1990, while Scotland and Wales have had one since 2000 and 2001 respectively. The 1997 Order supports the ‘Polluter Pays’ principle and provides a legal framework for dealing with historic contamination such as in illegal waste sites. It is fully retrospective in action and includes a provision for verification of the remediation to ensure that any pollution risks have been effectively managed. This would provide a degree of confidence to stakeholders that the site is not having an ongoing detrimental impact on the surrounding area. Despite recommendations from both the Comptroller and Auditor General (the C&AG) and the Public Accounts Committee, this important legislation has not been commenced.

Recommendation

The Department should propose a timeline for introducing the arrangements to give effect to the Environmental Better Regulation Act (NI) 2016 and the Waste and Contaminated Land (NI) Order 1997. The former legislation provides additional powers to assist the NIEA in combating waste crime, whilst the latter could provide a means of dealing with legacy sites impacted by contamination, particularly in instances where no-one can be made amenable.

2.8 The Department has stated that it has legislation that it can use to proceed with remediation. At the present time, these have not yet been used, however, the Department has advised us that to use any of these legislative tools creates significant financial risk and requires infrastructure not already available and additional project management resources.

2.9 This issue was also highlighted by Mills, who noted that the gap in legislation meant that very few previously discovered illegal (legacy) sites had been remediated or had the waste removed. He estimated that 466 sites, some now dating back over 20 years, could cost the public sector £250 million (at 2015 prices) to remediate. The NIEA told us that a limited assessment of environmental risk has been conducted using available data which indicates that most sites present a low risk to the environment. The NIEA continues to assess this issue.

Compliance monitoring activities are an essential part of regulating the management of waste

2.10 Compliance monitoring provides assurance that licensees are adhering to the regulations, while also providing a framework to address and deter non-compliance. Effective compliance monitoring should allow the NIEA to identify, analyse and prioritise regulatory risks, and undertake appropriate compliance activities to help mitigate those risks. It should enable consistent and transparent enforcement decisions to be taken (see Part 3) where non-compliance is detected. As noted previously, the NIEA operates on the basis of full cost recovery for its regulatory waste activity and its regulatory effort is focused on waste management sites where the bulk of waste-related fees are generated, rather than always being targeted on the areas of greatest environmental risk.

2.11 The NIEA uses a simple risk-assessment model to determine the number of compliance visits based on:

- Type of site – covers waste types and activities;

- Size of site – relative size of site/waste handled for that type of facility;

- Location – proximity of sensitive receptors – any natural or constructed feature that may be adversely affected e.g. homes or schools – and the level of complaints in last 12 months;

- Compliance score – from compliance assessment scheme; and

- Enforcement – warning letters, notices, and prosecution cases in last 24 months.

2.12 Sites are scored for each of the attributes above and, based on the score, graded as high, medium, or low risk. There is a pre-set number of scheduled visits for each level of risk, dictated by the NIEA Risk Assessment Model. Currently, for WMLs it is six visits for high-risk sites, four for medium risk and two for low-risk sites. For PPC sites, it is eight for high-risk sites, four for high/medium risk sites, two for medium-risk sites and one for low-risk sites. The number of visits has significantly reduced over recent years. For example, in 2017-18 there were 12 visits for each high-risk site and now there are either six or eight. Details of the total number of monitoring inspections are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Number of monitoring inspections

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | |

| Waste PPCs | 310 | 263 | 159 | 146 | 243 | 234 |

| Waste Management Licence | 970 | 983 | 724 | 779 | 884 | 842 |

Source: NIEA

2.13 The reduced level of inspection means that the system is more reliant on self-regulation, which can increase the risk of divergence from the regulations. It is important that the NIEA keeps its approach to inspection under review to ensure that monitoring activities are robust, targeted and effective.

The NIEA’s inspection work is not always targeted at areas of highest environmental risk

2.14 There are two types of monitoring inspections;

- Scheduled; and

- Unscheduled.

Unscheduled inspections are inspections that deal with complaints, planning permission, advice, and pre-application discussions, while scheduled inspections relate to all other inspections. The NIEA informed us that the majority of both types of inspections are unannounced, although they were unable to provide a breakdown of the total figures between announced and unannounced inspections.

2.15 The number and level of inspections is determined by the completion of a risk assessment and can comprise:

- a desk inspection;

- a basic visual inspection;

- a review of site paperwork to ensure compliance with waste licences and permits;

- checks to verify waste materials delivered and deposited on site are consistent with waste transfer notes; or

- the matching of waste inputs and outputs.

The NIEA does not hold statistics for the number of the different levels of inspections conducted.

2.16 The NIEA have stated that there have been no inspections conducted in the last two years where either site inputs are matched to outputs, or where waste materials are verified on-site. The NIEA advised that these inspections have been paused since 2023 as they are not a statutory requirement and resource constraints have required the Agency to prioritise delivery of its statutory obligations. Inspections involving the checking of Waste Transfer Notes are especially important for facilities that are not the final destination of the waste. They enable waste to be tracked to ensure that it does not end up in an illegal dump. Case Study 1 highlights an example of where waste had been processed and baled prior to its arrival at the final site. More frequent inspection of waste transfers between sites would help reduce the likelihood of such instances occurring. The verification of waste deposits ensures that the materials deposited do not detrimentally impact on the environment, or create a potential hazard for future generations to address such as in the case of Mobuoy.

Case Study 1

In May 2016, the NIEA reported that an illegal waste site was linked to a number of sites that had previously been discovered in other areas of the same county. The NIEA believed that the waste dumped at those sites originated in the RoI and estimated that the collective total volume was over 30,000 tonnes. It equated this to 12 olympic-sized swimming pools filled with rubbish. In a media release at the time, the NIEA commented that it would take considerable effort to transport and dump rubbish on such a large scale.

Source: NIEA

2.17 Most cases of illegal dumping will have involved a waste carrier at some point. Checking of waste carrier documentation could potentially prevent such crimes from being committed or identify them on a more timely basis. If the waste in Case Study 1 originated in the RoI as the NIEA believes, then it is the responsibility of the Irish Government to fund the cost of cleaning up the waste.

2.18 In our 2024 Review of Waste Management in NI report, we identified that there are no accurate figures for the extent or classification of approximately 87 per cent of the waste generated in NI. The approach to managing waste is therefore poorly informed and this may provide increased opportunity for criminal activity in the sector. The need to strengthen the systems for monitoring and analysing waste was also included as a recommendation in the Mills Report (Appendix 1 – Key recommendation 7). This issue is not specific to NI and the UK government is currently in the process of introducing a mandatory UK-wide digital tracking system.

Joint waste and water inspections are the exception

2.19 There are strict controls on waste management facilities in relation to the discharge of substances and materials into the land, surface water (rivers, lakes, loughs, streams reservoirs and canals) or groundwater (all water located underground in the cracks and spaces in soil, sand and rock). These functions are the responsibility of either the NIEA’s Water Regulation Unit or its Water Management Unit.

2.20 The NIEA told us that some inspections include a check of the surrounding area – this takes the form of a visual check from vantage points within the site. If any unauthorised activity is observed, the inspector notifies the Intelligence Branch for further investigation. We were informed by the NIEA that there were 11 joint inspections undertaken since 2014 involving the waste licensing and water management teams.

Some waste management activities do not require a permit or licence

2.21 Waste management activities that are considered to pose a low risk of harm to the environment and to human health do not require a permit or licence but still need to be registered with the NIEA. These activities are usually small-scale waste storage and waste recovery operations that are subject to specific limitations, for example, the tonnage they can handle. Depending on the nature of the activity, waste exemptions are valid for either one or three years.

2.22 Significant issues, such as minimal regulatory control allowing less scrupulous operators to take advantage of the waste exemption system, were identified by Mills. The review also identified that waste operations benefiting from exemptions were not always small scale or low risk, and the lack of a fit and proper person test meant that the system could be abused by those with relevant convictions.

2.23 Whilst there is an application fee charged for exempt sites, there is no programme of site inspections. The NIEA has told us that the funding obtained from these fees does not support an inspection programme. Risk-based compliance monitoring by the NIEA of this waste stream is crucial to obtain the necessary assurances that such waste is not being dumped illegally, and the site is not a pollution risk.

Recommendation

The NIEA should carry out a review of its inspection regime, to incorporate:

- the adequacy and frequency of compliance inspections, including:

- the review of transfer and consignment notes to identify waste that is not being disposed of legally;

- risk-based inspections for exempt sites; and

- joint waste and water inspections;

- the financial contribution of fees and charges towards the cost of the inspection regime; and

- the availability of robust and timely data and intelligence to enable resources to be effectively targeted at areas of most significant environmental risk.

Routine checks are not carried out on registered carriers

2.24 To transport any type of waste (excluding a householder who is removing their own waste to a household recycling centre), a person or business must be registered as a carrier with the NIEA. Once registered, the person or business can carry any type of waste, including commercial, industrial, household and even hazardous waste. The NIEA told us that the legislation places no restriction on the number, size, or type of vehicles covered by the registration. Registrations are for an initial period of three years, after which they can be renewed for additional three-year periods. The registration charge for carriers does not change to reflect the nature of the waste, nor the volume carried.

Recommendation

The NIEA should review the requirements in place for operators to be registered to trade legally in the waste sector. In particular, the NIEA should consider the requirements and standards for those wishing to transport hazardous waste or waste in significant volumes.

2.25 For most individuals and businesses, their first interaction with the waste management industry is via their waste carrier. Waste producers therefore place reliance on carriers to provide reliable advice and ensure that their waste is being managed legally. Presently, there is no routine inspection regime for registered carriers, but the NIEA told us that offence checks are conducted at initial registration and renewal. The NIEA informed us that it also carries out periodic stop and search operations in combination with the PSNI and HMRC, although only one such operation took place during 2023-24. Where unregistered operators are identified, enforcement action is taken. A review of the single carrier registration fee may provide an opportunity for the NIEA to introduce an inspection regime for registered carriers. The current carrier registration fee provides opportunities for those seeking to exploit the system.

Waste management licence holders and pollution prevention and control permit holders must pass a ‘fit and proper person’ test

2.26 The NIEA complements its system of compliance inspections with a ‘fit and proper person’ test. The test considers a range of factors including the nature and gravity of any previous specified offences committed, and whether the applicant or licence holder has had a previous application refused or failed to comply with the conditions or limitations of a licence or permit. The test has three elements; prescribed offences; technical competence and financial assurance, and these are explored in more detail below. The Mills review criticised the fit and proper person test, stating that its weaknesses made it relatively easy for criminals to operate in the waste management sector. Despite this, there have been limited legislative changes to the requirements.

Technical competence

2.27 Since 2022, the NIEA can grant a licence if the applicant has registered with the Chartered Institute of Waste Management or the European Union (EU) Skills. The applicant then has two years to gain an Operator Competence Certificate to meet the technical competence criteria.

2.28 One of the ongoing conditions of the licence is that the technically competent person must be in a position to control the day-to-day activities at the licensed site, and personal attendance at the facility forms a key element of site management. Since 2011, no applications have been refused, nor have any licences been revoked for failure to meet this requirement. The NIEA advised that their staff check site diaries completed by the operator to confirm the technically competent person is in regular attendance at the site.

Financial Assurance

2.29 The objective of this component of the fit and proper person test is for the licence holder to provide evidence that they have adequate funding available to address the potential environmental and human health implications of the waste activity they are undertaking.

2.30 An internal audit review of the financial assurance provisions in January 2024 noted that there were significant gaps in the information provided by waste operators, with no financial assurance having been provided for approximately £7.6 million of the required provision assurances. Additionally, the review noted that it was not clear whether a further £10 million of financial assurance provisions were up to date. The potential for companies to default is a concern, since this increases the risk that the public sector may be liable for any clean-up cost in the event that a clean-up is needed. The NIEA stated that it is currently unable to meet the target set out in its policy, which requires the financial assurances provided by all waste operators to be reviewed on an annual basis.

2.31 In particular, especially for landfill sites, there are potential risks around taking assurance from Parent Company Guarantees (PCGs) – where a parent company guarantees the subsidiary company’s financial health. These involve highly complex legal contracts, and an internal audit report highlighted that the NIEA has neither the trained staff nor sufficiently developed procedures to ensure that the financial obligations could be legally enforced.

Recommendation

The NIEA should review the adequacy of the current system for obtaining financial assurance on waste operators. This work should include ensuring that the required financial assurances are obtained for all waste operators on an annual basis as specified in the organisational policy.

Part 3: Enforcement

Incident reporting by the public is important in identifying waste crime

3.1 The NIEA’s Environmental Crime Unit (ECU) was established in 2008 in response to the Criminal Justice Inspection’s 2007 report – Enforcement in the Department of the Environment. The ECU reviews incidents and, where necessary, investigates and criminally prosecutes serious and persistent breaches of the law.

3.2 Breaches of compliance with waste management regulations can be identified in a number of ways. These include site inspections, reports from Councils and members of the public, engagement with the PSNI, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in RoI, Dublin City Council’s National Transfrontier Shipment of Waste Office and the UK Environment Agencies. Incidents range in scale from fly-tipping to the dumping of waste from fuel laundering facilities.

3.3 The NIEA has a dedicated phone line and a link on the NIDirect website for members of the public to report their concerns. Both are staffed during working hours, while an answer machine is in place at all other times. The NIEA’s water pollution helpline, however, is monitored continuously, and, because of this, a 2017 internal review recommended that a joint automated helpline for pollution and waste crime incident reporting should be established.

3.4 All relevant incidents are recorded, and an assessment is carried out to identify the level of risk to the environment. The number of waste incidents reported has been reducing over the last few years from 845 in 2016 to around 576 in 2023. In the 12-month period to October 2024, there were 541 reported incidents. These were assessed and allocated to teams within and outside the NIEA as most appropriate to be addressed. The breakdown of responsibilities for these incidents is shown in Figure 6.

Recommendation

The NIEA should review the methods and accessibility for the public to report their concerns about potential waste crime, including promotion of these in conjunction with the arrangements for reporting water pollution incidents. This would help ensure that waste crime and water pollution are given equal prominence in the minds of the public as important issues in the fight to protect the environment.

Figure 6: Responsibility for reported waste incidents (October 2023 – October 2024)

| Body | Reported waste incidents |

|---|---|

| Environmental Crime Unit | 371 |

| Councils | 98 |

| Other DAERA and NIEA | 49 |

| Contractor | 16 |

| Planning Enforcement Teams | 7 |

| Total | 541 |

Source: NIEA

The ECU investigates serious environmental offending

3.5 The most serious kinds of environmental offending, ranging from unauthorised landfilling and dumping of fuel-laundering waste through to unauthorised vehicle breaker yards, are investigated by the ECU. It has a dedicated financial investigation section, with staff formally accredited by the National Crime Agency (NCA) in the conduct of investigations, including confiscation and restraint.

3.6 Despite the importance of their role, and the fact that Mills reported that organised crime was involved with the waste industry in NI, the NIEA does not utilise key investigative powers such as surveillance under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000. They are unable to use these powers as there is no training, no processes, nor infrastructure in place to enable staff to operate in accordance with the legislation. It is therefore more difficult for the ECU to operate to its full potential and effectively counteract criminal activity without being able to utilise the full range of powers that are available to other environmental agencies across the UK.

3.7 Furthermore, the ECU does not have access to communications data under the Investigatory Powers Act 2016, as the NIEA informed us that the Department did not take the opportunity to ‘opt-in’ to the legislation, when it was updated from the previous Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000. The ECU told us that certain material and lines of enquiry are not available to it, for example, data from automatic number plate recognition, from social media applications and from mail providers to help in the identification, tracing and location of subjects of interest.

3.8 The NIEA highlighted that it has experienced considerable problems around the recruitment and retention of key staff. At the time of compiling this report, the NIEA stated that there were 22 staff vacancies within the ECU, which includes a number of specialist posts. These specialised roles include Financial Investigators, Crime Analysts and Intelligence Officers.

3.9 The Mills Report (Key Recommendation 5) suggested that the NIEA should explore the potential for recruiting specialist staff jointly with other regional environment agencies. This would enable these scarce resources to be shared across bodies and potentially help in the identification of crimes that have a cross regional/border aspect to them. NIEA has not at the present time explored this option.

Recommendation

The NIEA should explore all potential solutions to the current recruitment and retention challenges and establish a workforce strategy and corresponding recruitment plan to address those challenges. This should incorporate the potential for accessing specialist skills in conjunction with other regional environment agencies.

Criminal proceedings are a last resort

3.10 Criminal proceedings are usually only commenced by the NIEA after the perpetrator has been given time to address any non-compliance. The NIEA told us that in line with the Department Enforcement Policy, it will take a graduated and proportionate approach to enforcement in consideration of level and significance of non- compliance. In the case of the regulated sector this may, as a first step, entail working with the operator to bring them back into compliance. They also informed us that, until conclusion of any court proceedings, sites where illegal activity has been identified are monitored on an ongoing basis by a case officer and supervisor, with follow-up inspections being carried out based on the circumstances of the case and any ongoing environmental risks. This can sometimes result in the illegal activity continuing long after it has been identified, as in Case Study 2 where the perpetrator had almost two years to rectify the situation, before pleading guilty to their crimes in court.

Case Study 2

The site in County Down was visited on various occasions from November 2017 to February 2019 by NIEA staff. During each of the visits, inspectors identified waste that had been deposited on the site. The site did not have a licence to either keep or treat waste. Approximately 1,000 tonnes of waste was discovered on the site, including soil, metals, plastics and concrete. After the first visit, the NIEA issued a notice of non-compliance with the law and an action plan for the defendant to remediate the site. The defendant did not follow the action plan to address the issues identified, and the site remained in breach of NI’s waste management legislation.

The defendant pleaded guilty in September 2019 to eight charges under the Waste and Contaminated Land (Northern Ireland) Order 1997 and received a fine of £4,000. This site has not been remediated, however, if this waste had been disposed of properly it would have cost the defendant approximately £177,780.

Source: NIEA

The clean-up costs of illegal waste can result in a significant financial burden for the public sector

3.11 In February 2012, the NIEA uncovered an illegal dump at Mobuoy, County Londonderry. At an estimated 635,000 tonnes of illegally deposited waste, it is one of the largest illegal dumps ever discovered in Europe. Part of the site was an NIEA regulated site, with a long history of repeated non-compliance for various reasons. However, there was also a wholly illegal waste dump on the site. The NIEA estimates that there is a total of approximately 1.6 million tonnes of waste on the site. The clean-up costs are currently estimated to fall somewhere between £17 million and £700 million, with the most reliable estimate suggesting a cost of £107 million. It is expected that these costs will largely fall to the public sector to fund.

Profits from illegal dumping outweigh the sanctions

3.12 In the years 2019 to 2024, the NIEA secured 52 convictions for waste crime offences. 17 of those cases resulted in suspended sentences for the perpetrators and none resulted in a custodial sentence. However, recent confiscation orders using the Proceeds of Crime legislation have resulted in considerable financial penalties. The use of this legislation has its limitations however, as the NIEA is required to identify how much the defendant has profited from their crime, with the level of the Confiscation Order based on this figure and the defendant’s ability to pay, rather than the cost of remediation of the damage that has been caused to the environment.

3.13 However, as noted in a recent Office of Environmental Protection (OEP) report, criminals are skilled at protecting their assets and fines are relatively insignificant when compared with the profits that can be realised and the low risk of detection – see Figure 1. OEP highlighted that, as a result, criminals, often in organised networks, can become involved in waste crime on a wide scale. In 2022, the Head of the Environment Agency in England, in a speech to a Let’s Recycle and Environmental Services Association event, suggested that waste crime is attractive as the rewards are high, the chances of being caught are relatively low, and the penalties, if caught, are light.

3.14 It is therefore important to have a system to track where our waste is generated and where it ends up. There is no requirement for a waste producer to track the ultimate destination of their waste. Case Study 3 outlines an example where waste had been processed and baled, before being burned and otherwise illegally disposed of.

Case Study 3

On a rural site in County Tyrone, the NIEA identified over 5,300 tonnes of controlled waste that had been deposited and buried. Much of this waste was buried in agricultural land used for grazing, while other deposits were close to homes. Some of this waste had also been burned.

The waste identified included domestic, commercial and industrial waste, and comprised food packaging waste, crushed glass waste, mixed household waste, metals, tyres, shredded and flaked plastics and green waste. The waste was processed and baled prior to arrival at the site.

The case went to court in September 2018 and the defendant pleaded guilty to five charges under the Waste and Contaminated Land Act. The defendant received 240 hours of Community Service and a Confiscation Order for a nominal amount of £1, as the defendant was bankrupt.

Source: NIEA

Punishment for waste offences does not always fit the crime

3.15 To prevent waste crime, a range of compliance and enforcement measures must be in place. One such measure should be that perpetrators of illegal activity must face a punishment that dissuades them from committing the crime in the first place, or from re-offending. As noted above, the penalties for waste crime are low in comparison to the costs of disposing of the waste legally. Evidence to the Mills Review identified that the penalties were lower in NI than the rest of the UK. The report criticised the sentencing for those convicted of waste crime as too lenient to provide an effective deterrent and called for sentences comparable to the rest of the UK. Figure 7 shows a breakdown of the financial outcomes of criminal investigations since 2019.

Figure 7: Financial outcomes from criminal investigations 2019 to 2024

| Year | No of Convictions | Value of Fines £ | No of Confiscation Orders | Value of Confiscation Orders £ | Amount of Waste Detected (tonnes) | Approximate cost of Legal Waste Disposal £ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 16 | 61,050 | 6 | 230,213 | 31,968 | 7,190,694 |

| 2020 | 3 | 5,750 | – | – | – | – |

| 2021 | 4 | 4,000 | 2 | 412,583 | 15,065 | 2,914,380 |

| 2022 | 9 | 16,300 | – | – | 65,999 | 4,546,770 |

| 2023 | 9 | 7,400 | 2 | 256,544 | 22,734 | 2,169,894 |

| 2024 | 11 | 3,050 | – | – | 16,808 | 307,683 |

| Total | 52 | 97,550 | 10 | 899,340 | 152,574 | 17,156,511 |

Source: NIEA

3.16 The Mills Report suggested more extensive use of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 to provide a more effective deterrent. A significant measure that the NIEA has at its disposal is the Confiscation Order – potentially enabling it to secure financial recovery following criminal activity.

3.17 A Confiscation Order, however, can only be raised where the perpetrator has financially benefitted from their crime, and if they have the financial resources to pay any penalty. The latter criterion can sometimes result in little financial return being derived from the process, as was illustrated in Case Study 3 where a nominal amount of only £1 was recovered. However, the NIEA can re-visit the Confiscation Order and increase the amount of the penalty if the person’s financial circumstances change.

3.18 Obtaining a Confiscation Order can take a considerable amount of time after the perpetrator has been found guilty of their crime by the courts. In Case Study 4 the confiscation order hearing only took place three and a half years after the criminal hearing.

Case Study 4

In May 2015, officers of the NIEA commenced a criminal investigation into the unauthorised deposit, keeping and treating of controlled waste. Towards the end of the year, the NIEA conducted intrusive surveys at the site and discovered the presence of 13,867 tonnes of construction and demolition waste and household waste.

In May 2019, the defendant pleaded guilty in the Crown Court to three offences contrary to Article 4 (1) (b) & (c) of the Waste and Contaminated Land (Northern Ireland) Order 1997 and received a three-year suspended sentence.

Following conviction, confiscation proceedings were commenced. However, proceedings were delayed, concluding in March 2023, when a Confiscation Order was made by the Crown Court totalling £236,544.

Source: NIEA

3.19 Under the Asset Recovery Incentivisation Scheme, the NIEA receives 22.5 per cent of the money obtained under a Confiscation Order, with the remainder divided across the Department of Justice (DoJ), the Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland and the NI Courts and Tribunal Service. However, there are restrictions on the use of any money received. The money must be used in the financial year in which it is received and it must be used to ‘fight crime’. It therefore cannot be used to remediate the polluted land and where it is received late in the financial year, it is difficult to use the money within the permitted timeframe. If the money is not used in line with the scheme rules, it is surrendered to HM Treasury and lost to the NI Block. In the last five years, the NIEA has surrendered approximately £80,000 of incentivisation funding to HM Treasury as it was not possible for it to be used in line with the scheme rules.

3.20 The level of funds received by the NIEA via Confiscation Orders in the last five years has fluctuated significantly. For example, £0 was received in 2020 and £412,000 was received in 2021. The variation in the amounts of money received brings challenges, as it makes it difficult to project receipts and use them in the most effective manner.

3.21 Due to the limitations involved with the use of Confiscation Orders, the ECU is currently exploring the use of Compensation Orders. Since the proceeds of Compensation Orders do not have to be divided between other law enforcement partners, the whole amount granted by the courts will be received by the NIEA. They can only be used in limited circumstances where there is a proven debt or a reliable estimate for work that the NIEA has either already undertaken or committed to undertake. They can therefore be used to contribute to the cost of remediating damaged land, thereby directly reducing the requirement to use public monies.

Criminal proceedings are only considered in the most serious cases

3.22 The NIEA has advised that the ECU seeks to take enforcement action that is proportionate to the significance of the offence, influenced by the level and type of offending, the harm caused including impact on communities, the level of financial benefit arising or where non-compliance with remedial notices has taken place. For minor offences, the ECU will seek remediation, give advice and guidance, issue warning letters, or issue fixed penalty notices. For more serious offences, the ECU may submit a report to the Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland for consideration of prosecution. The NIEA has stated that in most cases, providing advice and guidance to operators and landowners is sufficient to bring offenders into compliance with the licensing regime, see Case Study 5.

Case Study 5