Abbreviations

BIF Belfast Investment Fund

DFP Department of Finance and Personnel

DoF Department of Finance

LIF Local Investment Fund

MPMNI Managing Public Money Northern Ireland

OBA Outcomes Based Accountability

OBC Outline Business Case

OFMdFM Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister

SIB Strategic Investment Board

SIF Social Investment Fund

SOA Super Output Area

Key Facts

£80 million SIF had a target to deliver £80 million of funding to projects across Northern Ireland

£93 million In 2016, the Social Investment Fund budget was increased to £93 million

9 zones Northern Ireland was divided into nine investment zones

68 projects The Social Investment Fund has allocated funding to 68 projects

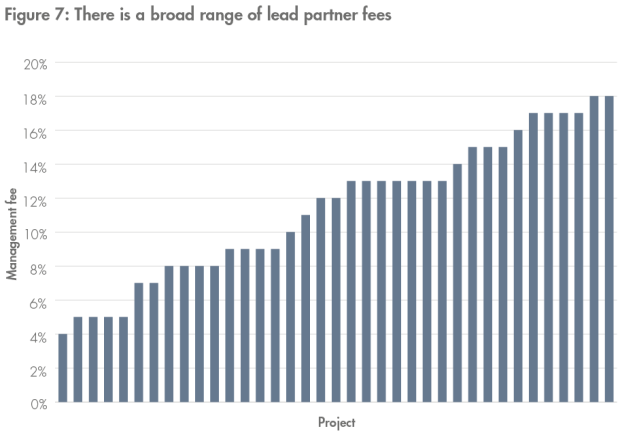

13% The average management fee is 13 per cent of project costs

£6 million In total, more than £6 million will be paid in management fees

18 projects 18 organisations linked to steering groups received capital funding

10% Our review identified increases in costs of over 10 per cent in more than half of capital projects.

31 projects 31 SIF projects are now complete

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. The Social Investment Fund (SIF) concept was agreed by the Executive in March 2011. SIF aimed to make life better for people living in targeted areas by reducing poverty, unemployment and physical deterioration. SIF was a key commitment for the Executive Office (the Department) in the 2011-2015 Programme for Government and had a target to deliver £80 million of funding for projects between 2012 and 2015.

2. The final SIF programme included four strategic objectives:

- building pathways to employment by addressing educational underachievement, lack of skills, access to jobs and making areas more appealing to businesses;

- tackling the systemic issues linked to deprivation such as mental and physical health, substance abuse, becoming a young mother, antisocial behaviour and the ability of communities to work together;

- increasing community services by improving existing facilities and providing new facilities where needed; and

- addressing dereliction to make areas more appealing for investment and for those living there.

3. SIF split Northern Ireland into nine investment zones and was designed to engage the local community in each zone to identify and prioritise needs and propose associated intervention projects. Fundamental to this was the establishment of a steering group in each zone to oversee community engagement and to develop a prioritised plan that would include projects to address local needs.

4. SIF has now awarded funding of over £79 million to 68 projects: 49 capital projects that will make improvements to 115 individual buildings, and 19 revenue projects. Funding for individual capital projects ranges from £50,000 to more than £3.5 million, and for individual revenue projects from £816,000 to £3.3 million.

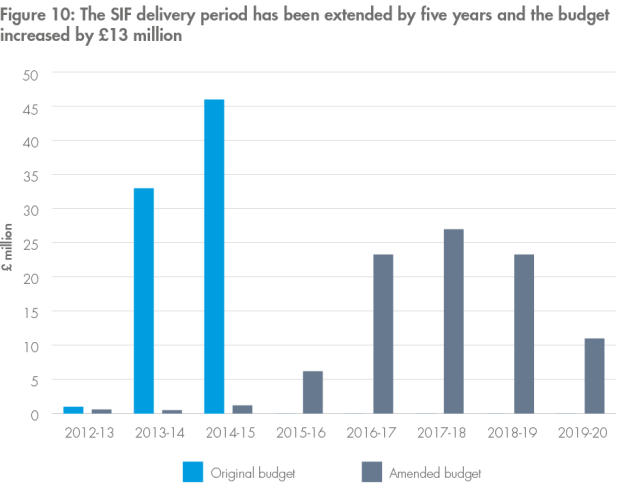

5. All SIF expenditure was expected to be incurred by March 2015. However in June 2016, the SIF delivery period was extended by five years and the programme will now run until 2019-20. To provide for supporting staff costs and potential cost increases in capital projects, the SIF budget was increased to £93 million. By 31 March 2018, SIF had spent £48 million.

6. Our report considers the processes established by SIF to identify local needs, and to develop and prioritise projects to address these needs. We have considered the management and delivery of SIF projects and reviewed some of the outcomes achieved by SIF projects to date.

Key findings

7. Steering groups began to meet in October 2012 and were required to deliver area plans, prioritising ten projects, which would address the needs of their zone, by 28 February 2013. Extensive engagement was the right thing to do as local people were best placed to identify the needs of their communities. However, meaningful community engagement is time consuming and the timetable provided was too short.

8. There was no formal application process for the submission of projects to SIF. This led to steering groups receiving large numbers of project proposals to consider. Some stakeholders highlighted that voluntary and community groups undertook a significant amount of work on proposals, which in the main was wasted effort. Many of those we spoke to during our audit told us that the area planning process raised expectations amongst the voluntary and community sector which caused frustration for all parties in the longer term. The Department advised that in any funding scheme, a balance needs to be struck between generating a wide range of ideas and managing the expectations of those making proposals. In our view, the Department should have provided more guidance to identify what type of projects would be eligible or likely to progress under SIF. In the absence of detailed guidance, steering groups adopted different approaches to project selection and prioritisation which meant that strategic decisions do not appear to have been based on need, but rather a means of reducing projects to a manageable number.

9. The processes used to prioritise projects lacked transparency and were inconsistent. Such variation in assessment processes gives rise to concerns over the robustness and transparency of project selection and prioritisation. Documentation does not exist to show clearly how ranking was carried out in each group. The Department did not require steering groups to submit scoring matrices with area plans, and therefore it does not hold a clear audit trail in relation to the award of public funding.

10. Our review of available documentation indicates that there was no consistent approach to prioritisation and the processes used to select and prioritise projects appear to have varied substantially between steering groups. The Department told us that it was not a requirement that all steering groups should apply exactly the same process as the overall approach to SIF supported flexibility for communities to use local discretion to tailor project priorities to local needs. However a clear scoring framework is important to ensure fairness for applicants and transparency in the award of public funding.

11. Governance arrangements for steering groups were lacking in key areas. Clear, consistent guidance is essential prior to the commencement of any scheme, but especially one in which decisions are being taken at arm’s length. SIF launched in October 2012, however final guidance notes were issued to steering groups on 19 December 2012, when groups were prioritising projects for area plans. In the absence of finalised guidance, steering groups largely decided on their own means of operation, which has led to inconsistencies in decision-making. The Department told us that it held a two day workshop in October 2012 for steering group members and in addition, Departmental representatives attended most of the steering group meetings to provide guidance and support. However, we noted inconsistencies in the quality of documentation, in particular steering group minutes, some of which lacked detail around how funding allocations and prioritisations were agreed. The Department does not hold minutes for some steering group meetings in February 2013 at which groups agreed the projects to be included in the area plan.

12. Conflicts of interest were not adequately handled. The design of SIF meant conflicts of interest were inevitable. This should have been a key consideration in the design of the scheme. In our view, the guidance that the Department produced for steering group members on dealing with conflicts of interest was inadequate. Members were advised that declaring a conflict and withdrawing from discussions was sufficient if there was no material benefit to the body they represented. However SIF involved the award of substantial funding to voluntary and community groups linked to steering groups, but the guidance failed to tell steering group members what to do in this instance. Organisations linked to steering groups have been awarded over £12 million of capital funding.

13. We identified three instances in which steering group members did not declare conflicts of interest. We also identified one case in which there was a potential conflict involving a Departmental representative. The Department told us that Departmental representatives were not formal members of a steering group and had no role in decision making. It was incumbent on the Department to ensure that guidance was fit for purpose, issued on a timely basis, and the procedures and processes that should have been in place were operating, and were seen to be operating, effectively.

14. Evidence from our audit work across the public sector suggests there is a role for additional expertise to support good governance and maintain high standards so that the wider public sector benefits from additional advice on matters of propriety and conflicts of interest.

15. Lead partners are responsible for the development, management and administration for 45 of the 68 SIF projects. The Department will pay more than £6 million in fees to lead partners for this work. The Department told us that lead partner fees are paid only on verified, eligible expenditure incurred by lead partner organisations. Costs vary significantly between projects from 4 per cent of project cost to 18 per cent. Projects vary significantly in scale and complexity with some having only one delivery strand and some having multiple strands with multiple delivery partners. Steering groups appointed lead partners during the area planning phase, without an open tender process, so it is not possible to confirm that value for money has been achieved with respect to the lead partner fees. Lead partners included 18 voluntary and community groups that each had a representative sitting on the steering group which appointed them. These eighteen organisations will receive over £4 million in lead partner fees.

16. All SIF expenditure was initially intended to be incurred in the three years to March 2015. The Department recognised this was an extremely ambitious target. The SIF delivery period has been extended by five years and will now run until 2019-20. In addition, the SIF budget has increased by over £13 million in order to meet up to £5 million of support staff and extended monitoring costs and £8 million of increased costs of capital projects, should it be required.

17. One factor which caused delay was the extensive reworking required for some projects because the original proposals were not of sufficient quality. In our view, the short time frame for area planning increased the likelihood that there would be issues around the quality of economic appraisals. Had a realistic timeframe and a standardised process been applied at the area planning stage, some of this additional work could have been avoided. We identified that project costs have increased by more than 10 per cent in over half of SIF capital projects.

18. Despite the extensive review and revision of economic appraisals, we have concerns around some projects and the extent to which they represent value for money.

19. Our review considered individual projects which are complete and identified outcomes to date which are promising. SIF has provided local communities with a number of benefits. Each project has developed relationships which should ensure that community organisations will continue to work together in future. Voluntary and community groups recognised that SIF gave prominence to issues such as unemployment and educational achievement in their communities. Many felt that for those individuals who had been able to participate successfully in employment, educational or early intervention schemes, there were potentially life-changing benefits.

Conclusions

20. We identified significant failings in the governance framework underpinning SIF. In the initial stages of the scheme there were a number of conflicts of interest which were not always appropriately dealt with. Documentation around project selection and prioritisation was poor and the scheme did not operate transparently. However, once projects began to become established, governance improved. It is critical that lessons are learnt and improvements are made when similar public spending schemes are being developed.

21. Many SIF projects have only recently commenced and 31 are now complete. It is therefore too early to conclude whether the programme is achieving value for money. We looked at some individual projects which are now completed and identified where outcomes to date are promising and value for money is likely to be achieved. However, we have also highlighted projects which we believe do not represent value for money. It is now important that robust arrangements are put in place for the Department to assess value for money at a programme level.

Recommendations

- Where significant community engagement is required, it is essential to ensure that adequate time is allowed to carry out consultation, develop and refine proposals and to ensure that the resulting plans are realistic, detailed and of sufficient quality.

- The Department is ultimately accountable for the decisions taken in awarding public funding to projects. Decisions concerning project selection should be clearly documented and the Department should ensure that it holds an audit trail of the process. A clear audit trail allows the Department to justify why decisions were made and demonstrate that assessment processes have been applied fairly, consistently and transparently.

- In the design of any new funding scheme comprehensive guidance to deal with conflicts of interest, real or perceived, and the associated procedures should be made clear to all those involved.

- We recommend, based on our audit work across the public sector, that arrangements are established to promote the highest standards in government on propriety, integrity and ethical issues, including conflicts of interest.

- Timely communication with those involved in projects, including those who are unsuccessful is key to ensuring transparency. The Department should have proper procedures for ensuring unsuccessful projects are notified and should provide feedback, setting out clear reasons for rejection.

- Given the importance of establishing the feasibility of major proposals prior to commencement, we recommend that the Department of Finance consider whether Managing Public Money Northern Ireland (MPMNI) should be updated to include this rationale, and if so update MPMNI as soon as possible.

- We recommend that the Department should put mechanisms in place to ensure good practice and learning points emerging from individual SIF projects are identified and shared with relevant public bodies.

Part One: Introduction and Background

The Social Investment Fund is one strand of The Executive Office’s Delivering Social Change framework

1.1 The Northern Ireland Executive established the Delivering Social Change framework in 2012 to tackle poverty and social exclusion. The Executive Office (the Department) (formerly the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister (OFMdFM)) is the lead co-ordination department for delivering the cross-departmental commitments contained within the framework.

1.2 A number of key issues that contribute to the continuation of poverty and deprivation were identified in the Delivering Social Change framework, including:

- low literacy and numeracy attainment;

- the need for parenting support and early intervention for children; and

- the lack of employment opportunities, coupled with local community dereliction.

1.3 A Delivering Social Change Fund established to enable the Executive to respond quickly and in a more flexible way to urgent social needs has supported:

- a Social Investment Fund (SIF) with £80 million for allocation to projects addressing deprivation;

- the development and implementation of nine Delivering Social Change Signature Programmes which fund projects at a cost of £88 million; three of these are jointly funded by Atlantic Philanthropies and are focused on Early Intervention and Transformation, Shared Education and Dementia; and

- a £12 million Childcare Fund.

SIF was established by the Executive

1.4 The First Minister and deputy First Minister brought forward a strategic paper on the Social Investment Fund concept, which was agreed by the Executive in March 2011. The agreed paper set out the broad parameters of the proposed Social Investment Fund including delivery in partnership with communities across a number of zones; an area based approach with local steering groups developing and agreeing area plans and the provision of technical support to assist steering groups in this process. SIF aimed to make life better for people living in targeted areas by reducing poverty, unemployment and physical deterioration. It was a key commitment for the Department in the 2011 -2015 Programme for Government under the priority “Creating Opportunities, Tackling Disadvantage and Improving Health and Wellbeing” and had a target to deliver £80 million of funding for SIF projects between 2012 and 2015.

1.5 The Department told us that SIF sought to be innovative in not following the conventional route to community investment through a centralised application based government grants fund but rather adopting a community co-design approach. A key feature of co-design is that communities have a significant role in decisions on local investment.

1.6 Following Executive agreement, a formal public consultation exercise on the operation of SIF commenced in September 2011. The consultation contained the proposed policy framework, including the establishment of steering groups, development of area plans, the strategic objectives, the mechanisms for administering funding and provision of technical support to the groups. The preferred options emerging from this consultation were incorporated in the final operation of SIF, which was agreed by the Executive in May 2012.

Four strategic objectives were identified

1.7 The final SIF programme included four strategic objectives:

- building pathways to employment by addressing educational underachievement, lack of skills, access to jobs and making areas more appealing to businesses;

- tackling the systemic issues linked to deprivation such as mental and physical health, substance abuse, becoming a young mother, antisocial behaviour and the ability of communities to work together;

- increasing community services by improving existing facilities and providing new facilities where needed; and

- addressing dereliction to make areas more appealing for investment and for those living there.

Nine investment zones were established across Northern Ireland

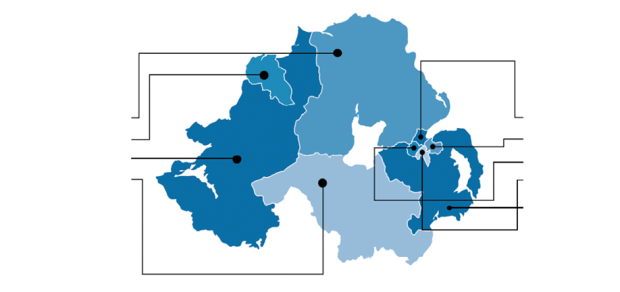

1.8 For the purposes of SIF, Northern Ireland was split into nine investment zones (see Figure 1):

- four zones in Belfast broadly following Assembly constituencies;

- one zone in Derry/Londonderry aligned to the then Council boundary; and

- a further four zones largely matching health and social care trust areas.

Figure 1: Northern Ireland was split into nine SIF investment zones

Source: The Community Foundation for Northern Ireland

1.9 Whilst the investment zones covered all of Northern Ireland, interventions are targeted at specific areas of deprivation. Eligibility was based on:

- areas within the top 10 per cent of Super Output Areas (SOAs) based on the multiple deprivation measure;

- areas within the top 20 per cent of SOAs based on the key domains of income, employment, education and health; and

- areas which can provide independently verified and robust evidence linked to the four strategic objectives of SIF.

SIF was designed as an additional fund to address specific social and economic issues within communities

1.10 A number of schemes aimed at addressing poverty, deprivation and social change already existed in other departments, ran concurrently with SIF and included:

- the Neighbourhood Renewal Programme (under the then Department for Social Development) which aims to bring together the work of all Government departments in partnership with local communities to tackle disadvantage and deprivation;

- the Extended Schools Programme (under the Department of Education) which aims to improve educational outcomes, reduce barriers to learning and provide additional support to children and young people from deprived areas; and

- Pathways to Success (led by the then Department for Employment and Learning) which is the strategy for those young people not in education, employment or training. Initiatives include a Community Family Support Programme focusing on the needs of the most disadvantaged families to enable young people to re-engage with education, training or employment and extended coverage of the Sure Start Programme targeted at the 25 per cent most disadvantaged ward areas over time.

1.11 Belfast City Council manages two funding streams which focused on similar projects. The funding streams ran concurrently with SIF.

- Belfast Investment Fund (BIF) was designed to support partnership projects across the city to have a substantial regenerative impact and bring major benefit to the city. £28.2 million has been ringfenced under BIF. Two of the schemes which have received funding in principle under BIF also received SIF funding; and

- Local Investment Fund (LIF), which was established to support neighbourhood projects to help regenerate local areas. The first two phases of LIF awarded £5 million and £4 million respectively to local projects. Despite being aimed at smaller projects, 13 projects which received LIF funding also received funding supporting from SIF. For a number of these projects the LIF and SIF funding was for different elements of the projects. Four projects were directly supported by both LIF and SIF for the same project proposal.

1.12 Projects proposed for funding under SIF were classified as either capital or revenue. Capital projects sought to develop derelict spaces or to make improvements to buildings which would allow the delivery of additional community services. Revenue projects focused primarily on training and employment programmes, early intervention services and providing educational support. Other revenue projects incorporated mental health services, community capacity building and social economy support.

SIF has awarded funding to 68 projects

1.13 SIF has now awarded funding of £79.1 million to a total of 68 projects across all nine zones (see Figure 2): 49 capital projects that will make improvements to 115 individual buildings and 19 revenue projects. Funding for individual capital projects ranges from around £50,000 to more than £3.5 million and for individual revenue projects from £816,000 to £3.3 million.

Figure 2: Almost £80 million has been allocated to 68 projects under SIF

|

SIF zone |

Total number of projects |

Funding awarded to projects (£ million) |

|---|---|---|

|

Belfast North |

8 |

9.3 |

|

Belfast South |

9 |

7.7 |

|

Belfast East |

11 |

7.5 |

|

Belfast West |

7 |

11.8 |

|

South Eastern |

8 |

7.6 |

|

Northern |

6 |

8.9 |

|

Southern |

7 |

8.7 |

|

Western |

9 |

8.1 |

|

Derry/Londonderry |

3 |

9.5 |

|

Total |

68 |

79.1 |

Source: The Executive Office

1.14 To provide for supporting staff costs and potential cost increases in capital projects (see Part Three), the overall SIF budget was increased to £93 million in December 2016. By 31 March 2018, SIF had spent £48 million.

Methodology

1.15 The study used a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods for gathering evidence. We met with a significant number of stakeholders directly involved in the programme including 8 of the 9 steering groups, 10 lead partners and 13 delivery organisations. We also met with a number of other interested parties. An overview of our study methodology is attached as an appendix.

1.16 Part Two of this report considers the processes established by SIF to identify local needs, and to develop and prioritise projects to address these needs. Part Three considers the management and delivery of these projects, while Part Four details some of the outcomes achieved by SIF to date.

Conclusions

1.17 Our review has identified significant failings in the governance framework underpinning SIF. In the initial stages of the scheme, there were a number of conflicts of interest which were not always appropriately dealt with. Documentation around project selection and prioritisation was poor and the scheme did not operate transparently. However, once projects began to become established, governance improved. It is critical that lessons are learnt and improvements are made when similar public spending schemes are being developed.

1.18 Many SIF projects have only recently commenced and 31 are now complete. It is therefore too early to conclude whether the programme is achieving value for money. Our review has looked at individual projects which are now completed and identified where outcomes to date are promising and value for money is likely to be achieved. However, we have also highlighted projects which we believe do not represent value for money. It is now important that robust arrangements are put in place for the Department to assess value for money at a programme level.

Part Two: Programme Governance: Steering Groups, Area Planning and Project Selection

2.1 The agreed Executive paper set out that SIF would engage the community in a local area to identify and prioritise local needs and propose associated interventions. It also specified the four strategic objectives of the Fund and the eligibility criteria. Fundamental to this was the establishment of a steering group in each of the nine SIF zones. The role of the steering group was to oversee and manage the area planning process, including community engagement and ultimately develop a prioritised area plan which would include projects to address identified needs. The economic appraisals for the projects within each area plan were considered by the Department and evaluated prior to any award of funding.

Steering groups were comprised of volunteers from a number of sectors

2.2 Departmental guidance stated that each steering group was to consist of not more than fourteen members with membership drawn from four sectors:

- four members from the voluntary and community sector;

- four members from the political sector;

- up to four members from the statutory sector; and

- up to two members from the business sector.

Members were not paid for their participation on steering groups.

2.3 There was a formal application process for representatives from the voluntary and community sector which required evidence of broad support from the local community. The First Minister and deputy First Minister made the final appointments in September 2012. Political representatives were selected by political parties in a proportion determined by the d’Hondt system, based on the 2011 Assembly election results.

2.4 Following the finalisation of each area plan in February 2013, steering groups were required to identify business sector and statutory representatives based on the needs emerging as part of the area planning process. A local council representative supported the steering group during the area planning process.

2.5 Representation from the business sector, in particular, varied across steering groups. Three steering groups had no business sector representation. Those that did appoint business representatives told us that there was a significant delay between the steering group nominating individuals and ministers approving the nominations. In one instance, a steering group nominated potential business representatives in December 2012. However, these representatives only attended their first meeting in May 2014, almost 18 months later. Steering groups indicated to us that the delayed appointments represented a missed opportunity to avail of the knowledge and expertise of the local business sector. The Department told us that ministers decided that business representatives would be non-voting members and therefore they did not have a role in determining local project priorities.

2.6 Each steering group was supported by a consultant and an observer from the Department. The role of the consultant was to:

- develop an engagement strategy and consult with the local community;

- use feedback from the consultation process to establish need within the zone; and

- assist in developing an area plan to be endorsed by the steering group.

The Department spent a total of £478,000 on consultants for the nine SIF zones.

2.7 Departmental representatives were allocated to support each steering group through provision of policy support, ensuring steering groups knew their obligations and escalating any emerging issues.

The Area Planning timeframe was too short

2.8 Steering groups were established in October 2012 with the first meetings held in October and November. Guidance Notes for the Area Planning Stage were issued to all steering groups on 19 December 2012. The notes provided guidance on the conduct of the steering groups, roles and responsibilities, conflicts of interest, area plan requirements and qualification and appraisal criteria for projects.

2.9 The Department required area plans to be produced by steering groups to identify the needs of the SIF zone and prioritise ten projects which would address these needs. In each zone the area plan was to be developed in consultation with the local community. Each SIF steering group developed its own approach to community engagement which generally involved public information sessions which provided an opportunity for community groups to highlight specific needs in their area.

2.10 Whilst there was no formal application process, community groups could submit potential projects to be considered by the steering group. This led to groups receiving large numbers of projects to consider. We noted one steering group that received 144 expressions of interest in respect of potential capital projects.

2.11 Some stakeholders that we talked to highlighted that the process demanded a significant amount of work from voluntary and community groups which in the main was wasted effort. Many told us that the area planning process raised expectations amongst the voluntary and community sector which caused frustration for all parties in the longer term.

2.12 The Department advised that in any funding scheme, a balance needs to be struck between generating a wide range of ideas and managing the expectations of those making proposals. In addition, it was made clear at the outset that £80 million was available across 9 zones and each zone should seek to include a maximum of 10 projects in the area plan.

2.13 In our view, the Department should have provided more guidance to identify what type of projects would be eligible or likely to progress under SIF. In the absence of detailed guidance, steering groups adopted differing approaches to selection and prioritisation. In one zone, for example, projects that were primarily sport, church or council based were excluded from consideration. These do not appear to have been strategic decisions based on need but rather a means of reducing projects that had to be considered by the group to a manageable number. In other zones, sport was a recurrent theme with SIF funding the construction of 11 3G pitches.

2.14 The Department told us that the strategic objectives and eligibility criteria were those set by the Executive and that it was for local groups, working within this strategic framework, to determine local priorities and projects in light of particular circumstances. This was consistent with the community led approach inherent in the SIF policy.

2.15 The area planning process was undertaken between October 2012 and February 2013 (see Figure 3). All steering groups told us that the timeframe was much too short, given the need to consult with the local community, identify, develop and prioritise projects, and produce economic appraisals for the ten prioritised projects identified in the area plan. This was complicated by the need to re-engage with the local community as a result of the decision, announced in December 2012, to extend the overall programme timeframe by an additional year to 31 March 2016.

Figure 3: The area planning process was undertaken between October 2012 and February 2013

- October 2012 Steering groups established

- 31 December 2012 Completion of community engagement

- 31 January 2013 Draft area plan with the Department

- 28 February 2013 Final deadline for submission of area plan and ten economic appraisals to the Department

Source: NIAO based on information from The Executive Office

2.16 Steering groups told us that the extensive engagement that they undertook was ultimately the right thing to do as local people were best placed to identify the needs of their communities. However, meaningful community engagement is time consuming and the timetable provided was much too short.

2.17 Steering groups told us that the shortcomings in the area planning process led to delays later. Many of the expressions of interest contained information that was speculative, lacked detail and required extensive work to complete a full economic appraisal. Steering groups told us that they and the projects would have benefitted from additional time to gather reliable costs and details. These delays are considered later in Part Three.

Recommendation 1

Where significant community engagement is required, it is essential to ensure that adequate time is allowed to carry out consultation, develop and refine proposals and to ensure that the resulting plans are realistic, detailed and of sufficient quality.

Funding allocations were announced nine months after the completion of area plans

2.18 The First Minister and deputy First Minister determined funding allocations to steering groups. The Department advised steering groups of their funding allocations in November 2013, some nine months after area plans had been submitted (see Figure 4). The total funding requested by steering groups exceeded the allocations by £52 million and as a result it was not possible to fund all projects which had been prioritised. Steering groups indicated that they would have preferred to have had knowledge of their respective funding allocations in advance of preparing their area plans. This, at the least, could have avoided nugatory work in the assessment of projects and disappointment among those groups whose projects were not funded under the programme.

2.19 The Department advised that it was widely communicated that the fund was limited to £80 million across nine zones and in programmes of this nature funding bids commonly exceed the amount of money available.

Figure 4: Funding requested by steering groups exceeded allocations by £52 million

|

SIF steering group |

Area plan request (£ million) |

Allocation (£ million) |

|---|---|---|

|

Belfast North |

15.0 |

9.0 |

|

Belfast South |

14.0 |

8.0 |

|

Belfast East |

12.0 |

8.0 |

|

Belfast West |

19.0 |

12.0 |

|

South Eastern |

9.0 |

8.0 |

|

Northern |

14.0 |

9.0 |

|

Southern |

14.0 |

8.5 |

|

Western |

14.0 |

8.0 |

|

Derry/Londonderry |

21.0 |

9.5 |

|

Total |

132.0 |

80.0 |

Source: NIAO based on information from The Executive Office

The processes used by steering groups to select and prioritise projects lacked transparency and were inconsistent

2.20 Steering groups were required to produce area plans containing a prioritised list of ten strategic projects. As funding was unlikely to be obtained for all ten projects, the prioritisation process played an important part in deciding which projects would ultimately be funded.

2.21 Some steering groups told us that once project ideas were submitted, they used a scoring matrix to prioritise projects. The Department does not hold these matrices as they were not required to be submitted alongside the area plan. As a result, we were only able to review one finalised and one draft scoring matrix out of the eight groups we spoke to, and were unable to fully review the selection and prioritisation process of all eight groups. In some cases, the lack of documentation has made the rationale for awarding funding to projects unclear (see Case example 1).

Case example 1: In some instances, records justifying decisions to award funding were incomplete

After expressions of interest had been collated, the Western zone steering group prioritised capital projects on the basis of a scoring matrix developed by the consultant and approved by the group. Of the 51 projects that were scored, the top five capital projects were prioritised in the area plan. “Halls Together Now”, a project to refurbish and extend St Macartin’s Cathedral Hall in Enniskillen, was not included in this top five ranking in the area plan. In a scoring matrix obtained by NIAO, it was the 27th highest scoring project. The Department told us that there was another stage in the assessment process as evidenced by the Area Plan. The Department told us that it was not able to provide details of the application of this second stage.

The Department also told us that in their opinion the undated matrix may not be the final matrix. We asked the Department for a copy of the final matrix but they told us they did not hold it.

The Department advised that following receipt of the area plan in February 2013, part of the agreed process was a review by Departmental officials of the ten proposals in the plan against both the SIF criteria and the agreed SIF appraisal criteria. This sift identified that all five capital project proposals did not appear to specifically meet the criteria or best fit the SIF objectives.

In April 2013 the Strategy Board noted their concern in respect of the high number of projects in the Western zone identified as not best fit for SIF. To address this, the Board asked officials to liaise with steering groups to highlight concerns with projects and look at refinement or alternatives.

At the June 2013 meeting, two prioritised capital projects were “deemed not to have met the SIF criteria” and as a result were “not proceeding in the process”. Steering group minutes then record that the Departmental official with the steering group Chair and some other steering group members had explored replacement projects which had been discussed with consultants outside of formal steering group meetings. The Department told us that replacement projects were from the zone’s informal “reserve list”. Steering group minutes stated that “Halls Together Now” was ranked between 11th and 15th place (the minutes suggest this project was 12th). However there is no documentation to justify why the ranking had changed.

Following the announcement of funding allocations to steering groups in November 2013, groups reconsidered projects in line with affordability constraints. The minutes indicate that the Departmental official informed the steering group that the two capital projects previously removed from the plan could, if the steering group wished, be reconsidered. This was due to a number of projects across other zones that the Department had previously sifted out, being reinstated. The steering group decided not to reinstate the original projects in the Western zone.

The steering group prioritised five projects with further selections to be made upon clarification of a number of issues.

In April 2014, as a result of another project securing alternative funding, which created budget availability in the zone, the steering group decided that “Halls Together Now” would receive funding of £542,000 as the group’s seventh project. The remaining monies would be held in reserve as a contingency. The final funding received by “Halls Together Now” was £870,000 due to unforeseen issues arising during the capital build.

The steering group told us that the decisions of prioritising were difficult to make, made even more difficult with the number and range of projects submitted and the amount of money awarded to the Western zone. Changes and amendments came about following ongoing deliberations and as new

information came to light but the procedures laid down were followed and the group considered it was diligent and fair.

Recommendation 2

The Department is ultimately accountable for the decisions taken in awarding public funding to projects. Decisions concerning project selection should be clearly documented and the Department should ensure that it holds an audit trail of the process. A clear audit trail allows the Department to justify why decisions were made and demonstrate that assessment processes have been applied fairly, consistently and transparently.

2.22 Our review of available documentation indicates that there was no consistent approach to prioritisation across different steering groups. Guidance provided by the Department to steering groups did include criteria which were included in the one draft matrix we reviewed. In practice, however, the processes used to select and prioritise projects appear to have varied substantially between steering groups.

2.23 In some zones, the steering group reviewed all projects that were submitted to it during public consultation events. In other zones, groups identified specific themes and attempted to prioritise projects that addressed these themes. One group identified specific types of projects that it felt should not be funded and excluded them from the assessment process. Some groups simply considered stand-alone projects which had no specific thematic link.

2.24 Some steering groups told us that ranking was carried out through group discussion and consensus. In one group, individual members submitted their rankings of each project to the consultants. However, documentation does not exist to show clearly what happened in each group. Such variation in assessment processes gives rise to concerns over the robustness and transparency of project selection and prioritisation.

2.25 The Department circulated final guidance to steering groups on 19 December 2012, when groups were prioritising projects for their area plans. The Department told us that at that time, it reiterated the requirement to apply consistently an agreed process for prioritising projects. It was not a requirement that all steering groups should apply exactly the same process as the overall approach to SIF supported flexibility for communities to use local discretion to tailor project priorities to local needs in line with the strategic objectives and eligibility criteria within the SIF policy. In addition, a Departmental representative was allocated to support each steering group alongside the appointed consultant and oversaw the prioritisation process. Minutes also provided confirmation of decisions reached but not the rationale or justification for those decisions. These decisions were then reinforced through the endorsement of the area plan by the steering group.

2.26 A clear scoring framework is important to ensure fairness for applicants and transparency in the award of public funding. Once projects are scored in this manner, it is important that these rankings are adhered to, taking account of the need to exercise reasonable flexibility in the light of changing circumstances and budgetary constraints. Case example 1 details an example where project ranking changed significantly following submission of the area plan to the Department.

Governance arrangements for steering groups were lacking in key areas

2.27 The Executive chose to develop a new scheme to allocate grant funding rather than use any pre-existing schemes administered by departments. Whilst a bespoke scheme can be tailored to achieve policy objectives, the creation of SIF greatly increased the risk that important controls could be omitted or overlooked. Our review noted a number of important areas where governance arrangements could have been improved.

Guidance was clarified too late in the process

2.28 SIF was launched prior to the finalisation and agreement of guidance for steering groups by the Department. Some steering groups told us that the lack of finalised guidance caused difficulties during the consultation process as they could not outline an agreed, clear and transparent process for the award of funding to those who had proposed projects. Clear, consistent guidance is essential prior to the commencement of any programme but especially one in which funding decisions are being taken at arm’s length.

2.29 Agreed guidance would have clarified the respective responsibilities and accountabilities of all of those involved in the process. It would also have encouraged greater consistency in decision making. Without finalised guidance, steering groups told us that they largely decided their own means of operation during the area planning process in particular. This has led to inconsistencies in how steering groups have approached decision making and in the decisions that have been taken.

2.30 The Department told us it held a two day workshop in October 2012 for all steering group members and appointed consultants, prior to the first meetings of the steering groups. This workshop provided overviews of the area planning process and area plan/project requirements, roles and responsibilities, presentations on each of the strategic objectives, statistical overview to support identification of need, economist requirements to inform development of economic appraisals, conflicts of interest, key dates and next steps. In addition, Departmental representatives attended most of steering group meetings to provide guidance and support from the beginning and throughout the process.

2.31 To ensure consistency of approach and transparency in decision making finalised guidelines should have been issued at the outset. Final guidance notes were issued to all steering groups on 19 December 2012, when groups were prioritising projects for area plans.

The operation of some steering groups could have been improved

2.32 We requested copies of all steering group minutes from the Department, but were told that in a small number of cases it does not hold all minutes. Amongst those missing were the records of three steering group meetings in February 2013 at which the groups agreed the prioritisation of projects and approved the area plans.

2.33 Our review of the available minutes of meetings highlights differences in the structure of meetings between steering groups. The Department produced guidance which provided a template agenda for meetings, although it does not always appear to have been used. We also note inconsistencies in the quality of documentation, in particular the minutes of meetings held by steering groups. Minutes are the sole record of actions taken and decisions made by the steering groups. Whilst minutes do record some key decisions made, some of the minutes we reviewed lacked detail around how funding allocations and prioritisation were agreed.

2.34 The Department advised that under the SIF arrangements the administration role, including minute taking, was assigned to the consultants appointed to each steering group and different styles were adopted by those responsible. Steering groups noted that there was a lack of administrative support available to them, particularly after the consultants’ involvement in the programme ended.

2.35 In addition we noted that, while steering groups made interim arrangements around chairing meetings, including rotation of the role of Chair, in most cases formal election of office bearers was not made until around or after the completion of the area planning process.

Conflicts of interest were not adequately handled

2.36 Any award of public sector funds should be as a result of a transparent and unbiased decision making process. Consequently, public bodies should ensure that conflicts of interest are identified and managed in such a way that safeguards the integrity of those making the decisions and maximises public confidence. Potential conflicts of interest should be disclosed where they arise and be clearly recorded, for example in minutes of meetings, along with the actions taken to avoid or mitigate the associated risks. This process is especially important in a scheme like SIF, where the design of the scheme made it likely that conflicts would inevitably arise. This should have been a key consideration in the design of SIF.

Organisations linked to steering groups have been awarded over £12 million of SIF funding

2.37 Of the 49 SIF capital projects, we have identified 18 voluntary and community groups which received capital funding from a steering group and which also had a director, trustee or employee who was a member of that group. In total, these bodies received more than £12 million of SIF funding (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Eighteen projects linked to steering groups received capital funding

|

SIF zone |

Capital projects linked to steering group |

Funding awarded to linked groups (£ million) |

|---|---|---|

|

Belfast North |

2 |

1.57 |

|

Belfast South |

5 |

3.10 |

|

Belfast East |

4 |

1.38 |

|

Belfast West |

2 |

3.94 |

|

South Eastern |

4 |

1.99 |

|

Northern |

1 |

0.46 |

|

Southern |

- |

- |

|

Western |

- |

- |

|

Derry/Londonderry |

- |

- |

|

Total |

18 |

12.44 |

Source: NIAO

2.38 The Department advised that it was aware of the potential for such conflicts to arise and therefore the guidance notes issued to steering groups in December 2012 explained: what a conflict of interest was; that even the appearance of a conflict can damage the group’s reputation; the need to establish a register of interests; and how a member should behave in the case where an item to be discussed or a decision to be made raised a potential conflict of interest. In addition, the Department advised that it had representatives at meetings who witnessed the application of the conflict of interest process.

2.39 In our view, the guidance the Department produced for steering group members on dealing with conflicts of interest was inadequate. Members were advised that declaring a conflict and withdrawing from discussions was sufficient if there was no material benefit to the body the member represented. Yet SIF involved the award of substantial grant funds to voluntary and community groups linked to steering groups (see paragraph 2.37). The guidance failed to tell steering group members what to do in this instance.

2.40 The Department told us that it is correct that the guidance did not specifically state the course of action that was required where the body a member represents could be receiving a material benefit. This was an oversight. However the guidance did state “In recording all their other interests openly, any actual or potential conflicts of interest can be identified more easily”.

Recommendation 3

In the design of any new funding scheme comprehensive guidance to deal with conflicts of interest, real or perceived, and the associated procedures should be made clear to all those involved.

2.41 Guidance also required conflict of interest forms to be completed by all steering group members but did not specify when. In most cases, returns were not made until around the end of, or after the completion of area plans by which stage project selection and prioritisation had already been done. Returns were not, therefore, routinely used as registers of interest to manage conflicts at steering group meetings, nor actively reviewed by the Department.

2.42 On the basis of our analysis at Figure 5, we reviewed conflict of interest declarations completed by steering group members. In three instances out of eighteen, we identified conflicts of interest that were not declared.

2.43 The Department told us that it had representatives at meetings who witnessed the application of the conflict of interest process. However, whilst all steering group members were required to complete a Conflict of Interest declaration, the Department did not require its own staff who attended steering group meetings or who worked on SIF to declare any potential conflicts. In our view this was an important omission. We identified one case in which there was a potential conflict of interest involving a departmental representative. The Department told us that Departmental representatives were not formal members of a steering group and had no role in decision making, including the development and prioritisation of projects.

2.44 We found inconsistencies in how each steering group dealt with conflicts of interest. Many groups told us that they completed conflict of interest declarations, potential conflicts were declared at the beginning of each meeting and individuals concerned left the room when relevant projects were discussed. However, only one steering group’s minutes record individuals leaving the room during discussions. One steering group told us that whilst they filled in the conflict of interest forms, they were not referred to again and they had no recollection of anyone ever declaring an interest in a project or excusing themselves from discussions.

2.45 Steering group members were themselves best placed to identify whether they had a conflict of interest. While ultimate responsibility for declaring any conflict rests on those individuals, it was incumbent on the Department to ensure that guidance was fit for purpose issued on a timely basis, and the procedures and processes that should have been in place were operating, and were seen to be operating, effectively.

The wider public sector could benefit from additional advice on matters of propriety and conflicts of interest

2.46 Evidence from our audit work across the public sector suggests there is a role for additional expertise to support good governance and maintain high standards. Whilst audit plays a valuable role in identifying lessons to be learnt following completion of schemes, issues of propriety and conflicts of interest should be considered during the design of all new schemes. In our view, arrangements should be established to provide advice on corporate governance, standards and ethical issues to promote the highest standards of propriety, integrity and governance within the public sector.

Recommendation 4

We recommend, based on our audit work across the public sector, that arrangements are established to promote the highest standards in government on propriety, integrity and ethical issues, including conflicts of interest.

There were inconsistencies in the level of engagement and degree of transparency steering groups had with their local communities

2.47 Transparency in the allocation of public funding is necessary to enable accountability and to promote confidence in public sector funding schemes. Steering groups were responsible for engaging with local communities and ensuring they were kept updated on the progress of SIF. Departmental guidance required that “details of meetings including action points, minutes and other group activities should be circulated to the wider community”.

2.48 However, a number of organisations that applied for SIF funding indicated they had limited engagement with the steering group throughout the process, particularly following completion of the area plan. There were inconsistencies in the level of engagement and degree of transparency steering groups had with their local communities. One steering group told us they wanted to be as transparent as possible throughout the area planning and delivery stages. Consequently, they circulated the minutes of their meetings and the final area plan to stakeholders via their own existing network databases. In contrast, we spoke to an unsuccessful applicant from a different zone who felt they were unable to get any meaningful feedback from either the steering group or the Department during the prioritisation and funding allocation process (see Case example 2).

Case example 2: After initial engagement, there was a lack of timely communication with the community

Following the submission of area plans, the Department carried out an initial review of projects. The Department told us this was based on the high level information available and conducted prior to any detailed review of economic appraisals. This review identified eight projects across all zones which did not appear to specifically meet the SIF criteria. In some, but not all instances, additional information was sought from the promoters of these projects.

Our review identified a project in Fermanagh which was not given an opportunity to submit further information. In June 2013 the steering group decided that this prioritised project on the Western zone area plan would not be proceeding in the SIF process. This decision was documented in the minutes of the steering group meeting.

In August 2013 the Department told the project promoter that all area plans and projects were currently under consideration and it could not give any indication of outcome or timescale. By September, in response to another request for information, the Department told the promoter that “Your project was listed as priority eight by the Steering Group. The process of assessment has taken longer than originally anticipated and therefore is as yet ongoing.”

In November, steering group minutes indicate that the Departmental official informed the group that this project previously removed from the plan could, if the steering group wished, be reconsidered. The steering group decided not to reinstate this project.

In March 2014, the Department wrote to the applicant informing them the project was ranked number eight of the ten which made up the area plan and that “your proposal remains under consideration”.

The project promoter received a letter in June 2014 from the steering group telling them they had been unsuccessful, seven months after the final consideration of the project in the process.

The Department told us that it was the responsibility of the steering groups to inform project promoters where capital projects were not progressing. The Department also told us that it requested that steering groups formally notify those engaged on the outcome of proposals. The Department stated that the Western zone was reluctant to relay the information, only finally agreeing to issue letters in June 2014 following ongoing requests by the Department.

The steering group told us that as the award and letter of offer to successful projects would come from the Department it considered that it was the Department’s duty to inform unsuccessful projects.

In our view, it is unacceptable that the Department and a steering group couldn’t agree on whose responsibility it was to inform applicants about the outcome of funding decisions. As a result, a community group was left waiting for an answer for over a year.

Recommendation 5

Timely communication with those involved in projects, including those who are unsuccessful is key to ensuring transparency. The Department should have proper procedures for ensuring unsuccessful projects are notified and should provide feedback, setting out clear reasons for rejection.

2.49 The Department told us that it does not accept this recommendation as it considers it had no relationship with those engaged by the steering group.

2.50 The Department told us that it was the responsibility of steering groups to maintain communication with those engaged and in their view it would not have been appropriate for the Department to provide feedback to those engaged by a third party. The Department told us that it provided confirmation to steering groups that communications should issue and continued to request this from the steering groups.

The ongoing role of steering groups is unclear

2.51 Initially steering groups were told by the Department that they would be responsible for overseeing, monitoring and reporting on the implementation of the area plan. However, more than a year after the completion of area plans in February 2013, the Department decided that this oversight role would fall to lead partners appointed to some projects and accordingly it issued revised guidance to steering groups (see Part Three). Many steering group members told us there is now a lack of clarity around the ongoing role and purpose of the steering group.

2.52 As a result, in a number of zones steering group meetings have become infrequent. When we met with steering groups in summer 2017, the majority had not met in over a year. In contrast, one group continues to meet on a quarterly basis, in line with the original guidance provided by the Department. Steering groups told us that, given the commitment and effort invested in compiling the area plan, they are disappointed that they have no role in assessing the impact of the projects in their local communities. Many are no longer aware of the status of projects or the overall progress against the area plan. Some steering group members told us that their group had lapsed by default. The Department advised that it has considered the future role of steering groups and has prepared advice on this issue. This will be the subject of future Ministerial consideration and decision in due course.

2.53 The Department advised us that the current state of progress of all SIF projects has been published on its website since November 2016. In addition, the Outcomes Based Accountability (OBA) methodology is used to monitor the impact of all SIF projects to ensure a focus on outcomes and the ability to determine how many people are better off as a result of the investment. All SIF projects have an agreed OBA scorecard prior to commencing and dashboards are produced quarterly and issued to the lead partner/project promoter and shared with the project board.

Part Three: Programme Delivery and Role of Lead Partners

Lead partners were appointed to manage the majority of projects

3.1 A key element in the design of SIF was the appointment of organisations to act as a ‘lead partner’ for individual projects. Lead partners are responsible for the development, management and administration of projects and have overall financial responsibility for each project. Lead partners also provide regular updates on project progress and performance to the Department. A lead partner has been appointed for 45 of the 68 projects being delivered by SIF (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: One third of projects do not have a lead partner

|

Capital |

Revenue |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Projects with a lead partner |

26 |

19 |

45 |

|

Projects without a lead partner |

23 |

0 |

23 |

Source: NIAO based on information from The Executive Office

3.2 The Department told us that where project promoters had the capacity to take forward capital projects and where steering groups were content, no lead partner was appointed. However, some steering group members told us that they resisted the appointment of a lead partner to their capital project in order to avoid losing some of the grant to lead partner fees. When they needed support they were able to refer back to the Department.

3.3 Lead partners were nominated by the steering group in each zone as part of the area planning process. Guidance from the Department stated that “where possible” the lead partner organisation should come from within the steering group. The Department told us that this was because steering groups had developed the projects and understood in detail the community needs driving the very specific focus of the projects. Of the 45 projects that have a lead partner appointed, 18 are voluntary and community groups linked to steering group members. The majority are statutory bodies (6) or local councils (21).

3.4 Many steering groups told us that the lack of clear guidance on the roles and responsibilities of lead partners from the Department proved to be an issue when it came to making appointments. A number of steering group members from the voluntary and community sector told us that they were unaware that their organisation might have to take on a project management role until guidance was issued in February 2013, prior to the formal appointment of lead partners. We also noted a number of instances where there appeared to have been a reluctance to accept the lead partner role.

The Department carried out a range of checks on organisations appointed as lead partners

3.5 The Department carried out a number of due diligence checks prior to the appointment of lead partners. This included a vouching and verification visit for each organisation, to confirm that adequate processes and controls were in place to manage SIF funding. These visits involved the review of a number of documents including audited accounts; a list of directors; the organisation’s strategic plan; financial processes and procedures; proof of other funding where applicable; and in the case of capital projects, proof of land ownership. These checks were performed to confirm that organisations had the procedures in place to manage public money. All organisations proposed as lead partners met the requirements of the due diligence checks.

3.6 The Department told us that part of the purpose of SIF was to assist community groups to build capacity. Therefore, where feasible and appropriate, the groups were assisted to put additional processes in place to strengthen their organisational capacity through recommendations made as part of the due diligence checks. However, we noted that the recommendations from the vouching and verification checks, which was part of the due diligence process, were not routinely followed up by the Department.

3.7 The Department advised that, following an Internal Audit review, recommendations covering issues of significant risk which require implementation prior to the release of funding are now followed up within an agreed period. More minor recommendations on issues which do not present a significant risk are not routinely followed up outside of the normal verification procedures. Therefore Departmental processes around follow up of recommendations are now being applied.

The Department will pay more than £6 million in fees to lead partners

3.8 Lead partners are reimbursed for the work they carry out in monitoring and managing projects, limited to a maximum of 20 per cent of the project cost, but based on actual costs incurred. The Department advised that the adoption of a management fee up to a maximum of 20 per cent was based on previous evidence that this model provides better value for money than the Department’s traditional approach to funding which included salary and overhead costs in the overall programme expenditure.

3.9 Costs vary significantly between projects, from 4 per cent of project cost to 18 per cent (see Figure 7). The average lead partner fee for a revenue project is 13 per cent of the total project cost and the average for a capital project is 9 per cent. In total, lead partners will receive more than £6 million in fees.

3.10 As lead partners were nominated by the steering groups during the area planning phase and not appointed via an open process, it is not possible to confirm that value for money has been achieved with respect to the fees that they receive. Fees of this nature and magnitude should have been subject to competition.

3.11 The Department told us that the proposal to have a lead partner and the associated costs were clearly set out in the outline business case for SIF and that lead partner fees are paid only on verified, eligible expenditure incurred by lead partner organisations. Eligible costs were agreed in advance with the Department and include staff wages, training, evaluation expenses and various administration costs. These costs are approved by the Department based on evidence of expenditure incurred.

Source: NIAO based on information from The Executive Office

3.12 The largest single fee for a revenue project is almost £590,000 for an employment project. The largest lead partner fee for a capital project is more than £250,000 for a community sport project managed by Newry, Mourne and Down District Council.

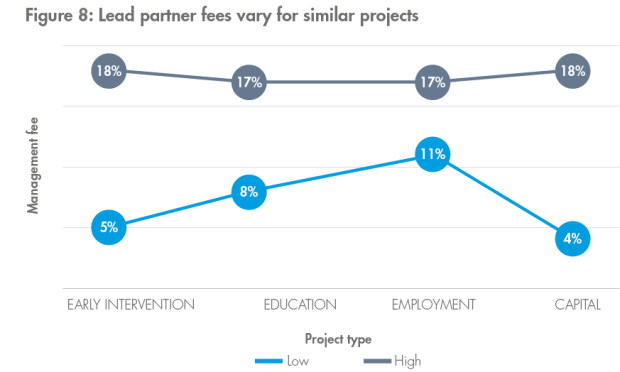

3.13 We have reviewed the list of lead partner fees and note that there is a range of fees for projects which have a similar theme. For example, there are four education themed projects for which fees range from 8 per cent to 17 per cent of total project costs (see Figure 8).

Source: NIAO based on information from The Executive Office

3.14 The Department advised that projects vary significantly in scale and complexity, with some having only one delivery strand and some having multiple strands with multiple delivery partners. Similarly some capital projects involve work to only one premises with only one Integrated Design Team and contractor appointed. Others involve works to multiple premises with multiple Design Teams and contractors. It is therefore not possible to compare the projects and associated lead partner costs on the assumption that all involve the same level of work.

3.15 The Department told us that where project promoters had the capacity to take forward their own capital projects, lead partner fees were not included in costs. However we noted four projects, managed by councils and involving council owned assets, where lead partner fees totalling more than £395,000 have been agreed. The Department told us that these projects were prioritised in direct response to community needs but that the councils did not have the capacity to take them forward themselves. Therefore, a small lead partner fee was required to make these projects viable.

The design of SIF meant conflicts of interest were inevitable

3.16 Given the design of the scheme and the participation of voluntary and community representatives on steering groups, conflicts of interest were inevitable. All eighteen of the voluntary and community groups that were appointed as lead partner organisations by a steering group had a representative sitting on that steering group. The Department’s guidance stated that “where possible” the lead partner organisation should come from within the steering group. As a result, conflicts of interest became inevitable in SIF (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Eighteen of the forty-five lead partners were voluntary and community organisations linked to the steering groups

|

SIF zone |

Number of projects with lead partners linked to steering groups |

Lead partner fees for organisations linked to steering groups (£ million) |

Total project costs (£ million) |

Lead partner fees as percentage of project costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Belfast North |

3 |

0.52 |

5.73 |

9% |

|

Belfast South |

1 |

0.29 |

2.19 |

13% |

|

Belfast East |

4 |

0.46 |

3.58 |

13% |

|

Belfast West |

3 |

0.84 |

5.58 |

15% |

|

South Eastern |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Northern |

4 |

1.08 |

7.69 |

14% |

|

Southern |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Western |

2 |

0.59 |

3.56 |

17% |

|

Derry/Londonderry |

1 |

0.38 |

3.33 |

11% |

|

Total |

18 |

4.16 |

31.67 |

13% |

Source: NIAO

Note: These figures do not include projects where councils acted as lead partner and received a fee.

3.17 Some steering group members themselves highlighted concerns in respect of potential conflicts of interest. One steering group recorded these concerns in their minutes, noting that they had submitted projects for consideration which their affiliated organisation would then be managing.

3.18 The design of the SIF scheme, the preference for lead partners to come from steering groups, and a lack of open tendering for lead partners has meant that individuals on steering groups are potentially unable to allay concerns that could be raised, such as impropriety. The Department clarified that it was not a requirement but a preference for lead partner organisations to come from steering groups because steering groups had developed the projects and understood in detail the community needs driving the very specific focus of the projects. In effect they were the project owners. The preference was initially to contract with the steering group but, given that they were not legal entities, this option was not possible. Whilst the role of lead partner was not subject to open competition, both the delivery organisations for revenue projects and contractors for capital projects were all subject to open procurement processes.

Delivery has been significantly delayed

3.19 All SIF expenditure was originally intended to be incurred in the three years up to March 2015. However, the Department told us that it has been recognised from the outset that this was an extremely ambitious target. The Department of Finance and Personnel, in their review of the outline business case in 2012, described this timetable as “hugely challenging”. It has not been feasible to maintain this timetable.

3.20 In June 2016, the Department of Finance approved a five year extension to the SIF delivery period and the programme will now run until 2019-20. In addition, the budget has increased from £80 million to £93.1 million (see Figure 10). The increase in budget will be made available to meet up to £5 million of support staff and extended monitoring costs and £8 million of increased costs of capital projects, should it be required.

Source: NIAO based on information from The Executive Office

3.21 In 2013 HM Treasury updated Managing Public Money, the guide for public expenditure in England, to enable Accounting Officers to require a ministerial direction in instances where the feasibility of a ministerial proposal is in doubt or where “there is significant doubt about whether the proposal can be implemented accurately, sustainably or to the intended timetable.” Managing Public Money Northern Ireland (MPMNI) does not contain this rationale.

Recommendation 6

Given the importance of establishing the feasibility of major proposals prior to commencement, we recommend that the Department of Finance consider whether Managing Public Money Northern Ireland (MPMNI) should be updated to include this rationale, and if so update MPMNI as soon as possible.

The protracted nature of the appraisal process has delayed delivery

3.22 Following the submission of area plans to the Department, individual economic appraisals were subject to a lengthy review process. This review aimed to quality assure the project proposals and to ensure that value for money was robustly tested. At Departmental level, projects under £1 million were reviewed by in-house economists and the finance team, while projects requiring more than £1 million of funding were also reviewed by the Department’s Finance Sub-Committee. A small sample of capital projects was reviewed by the then Department of Finance and Personnel (DFP). Finally, Ministerial approval from the First and Deputy First Minister was required before SIF funding was confirmed.

3.23 It was originally intended that the assessment process would take 16 weeks to complete. Initial guidance issued to steering groups by the Department indicated that Ministerial approval for successful projects would issue by 31 July 2013, with contracts in place by 31 August 2013. The first projects were approved in February 2014 almost a year after the area plans had been submitted.

3.24 The Department had limited experience in delivering a programme of this nature and scale. Staff therefore did not have a sufficient understanding of the complexities involved. Consequently, the Department underestimated the length of time and extent of work required to develop projects into robust proposals that were ready for approval.

Some economic appraisals required extensive reworking

3.25 Economic appraisals were prepared by external consultants for all 89 proposed projects across nine SIF zones as part of the area planning process. The Department paid these consultants more than £478,000 for their work on supporting the steering groups to engage the wider community, develop the area plans and projects within them and produce supporting economic appraisals.

3.26 A Gateway Review was completed in May 2013 following the completion of the area planning process. The purpose of this review was to check progress against plans and to confirm that the overall SIF programme objectives were being met. The Gateway Review report noted that “projects were (in the main) not of sufficient quality or completeness for the Programme to move forward, across the board, to the implementation stage.” The review concluded that “successful delivery of the programme or project is in doubt with major risks or issues apparent in a number of key areas; urgent action is needed to ensure these are addressed, and whether resolution is feasible.”