List of Abbreviations

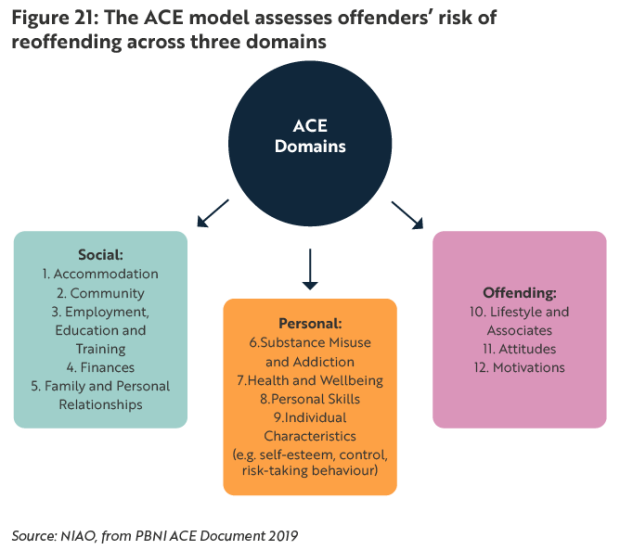

ACE Assessment, Case Management and Evaluation

AD:EPT Alcohol and Drugs: Empowering People through Therapy

APs Approved Premises

BASS Bail Accommodation and Support Service

BITC Business in the Community

BMC Belfast Metropolitan College

CJB Criminal Justice Board

CJI Criminal Justice Inspection (Northern Ireland)

CPO Community Payback Order

DfC Department for Communities

DoH Department of Health

DoJ Department of Justice

ECO Enhanced Combination Order

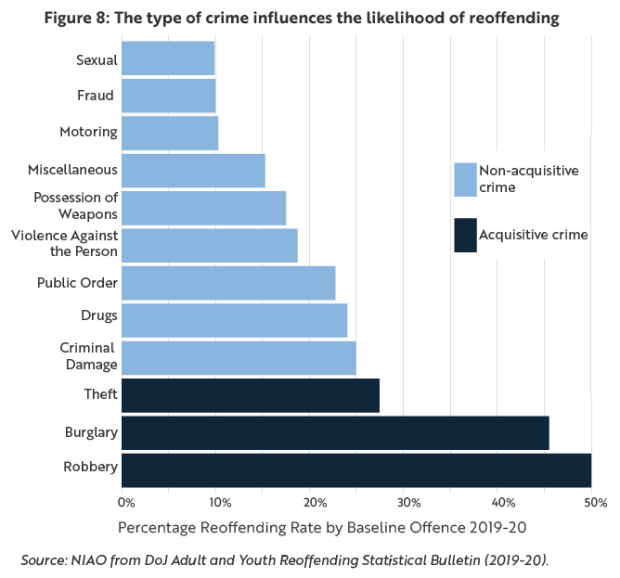

EM Electronic Monitoring

GPS Global Positioning Systems

HMIP His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons

HMPPS His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service

HR Housing Rights

HSC Health and Social Care

IOM Integrated Offender Management

IRC Independent Reporting Commission

MHC Mental Health Court

MoJ Ministry of Justice

NI Northern Ireland

NICS Northern Ireland Civil Service

NICTS NI Courts and Tribunals Service

NIHE Northern Ireland Housing Executive

NILC Law Commission for Northern Ireland

NISRA Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency

NIPS Northern Ireland Prison Service

NPS National Probation Service

NWRC North-West Regional College

OBA Outcomes Based Accountability

ODPs Outcomes Delivery Plans

OECD Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

PASS Presumption Against Short prison Sentences

PBNI Probation Board for Northern Ireland

PDM Prisoner Development Model

PDP Personal Development Plan

PDU Prisoner Development Unit

PfG Programme for Government

PND Penalty Notices for Disorder

POST Positive Outcomes for Short-Term Prisoners

PPANI Public Protection Arrangements for Northern Ireland

PPS Public Prosecution Service

PSJ Problem Solving Justice

PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland

PSR Pre-Sentence Report

ROD Reducing Offending Directorate

RoI Republic of Ireland

ROP Reducing Offending in Partnership

RRSOG Reducing Reoffending Strategic Outcomes Group

SEHSCT South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust

SLA Service Level Agreement

SMC Substance Misuse Court

TEO The Executive Office

UK United Kingdom

VCS Voluntary and Community Sector

YJA Youth Justice Agency

Key Facts

Offending and Reoffending

Approximately 31,000 offenders convicted in court or given an out-of-court disposal each year.

16% of adult offenders reoffended within one year in 2019-20.

10,000 reoffences committed by 3,000 adults in 2019-20 (more than 3 offences per reoffender).

Strategy and Costs

10 years since the Strategic Framework for Reducing Offending was published in 2013.

£16.7 billion annual estimated economic and social costs of adult reoffending in England and Wales. An equivalent estimate for Northern Ireland is unavailable.

£16.1 million direct annual funding for rehabilitation initiatives across both custodial and community settings.

The Prison Population - Short-term prisoners

77% of sentenced prisoners committed in 2021-22 received custodial sentences of 12 months or less.

52% of short-term prisoners reoffended within one year of release in 2019-20.

The Prison Population - Remand prisoners

37% of the prison population were held on remand in 2021-22.

1,300 individuals committed to remand in 2020 did not ultimately receive a custodial sentence.

Key Challenges to Rehabilitation

Accommodation

16% of prisoners were released from custody in 2019-20 with no identified accommodation.

Education and Employment

74% of prisoners in 2022 had left school at age 16 or under, and 32٪ had no qualifications.

Mental Health

45% of offenders assessed by PBNI between 2017-21 had some level of mental health issues which contributed to their offending.

Substance Misuse

66% of prisoners in 2022 reported having used drugs at some stage in their life.

Executive Summary

Background

1. The justice system aims to protect the public, bring offenders to justice, and support their subsequent rehabilitation to reduce overall offending levels. Within this, the Department of Justice (‘DoJ’ or ‘the Department’) formulates policy and oversees the strategic framework for several statutory bodies, principally the Northern Ireland Prison Service (NIPS) and the Probation Board for Northern Ireland (PBNI), who work closely with the voluntary and community sector (VCS) in delivering various rehabilitation programmes and initiatives.

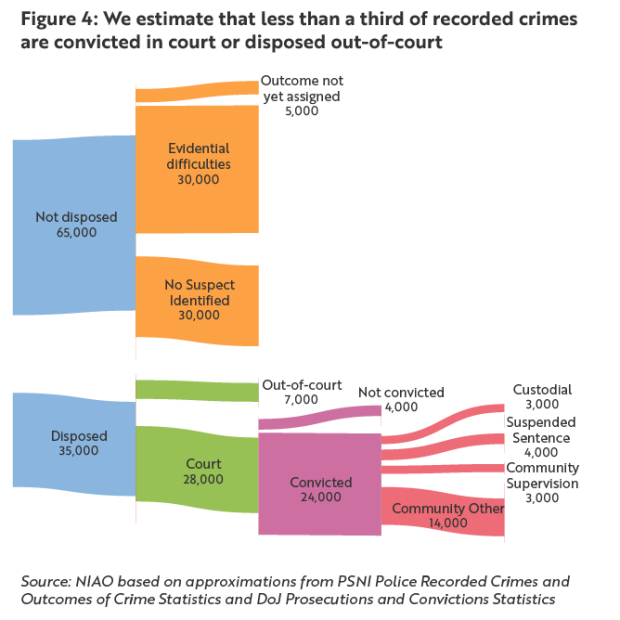

2. Around 100,000 crimes are reported to the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) each year. As a result, 24,000 people are convicted in court of criminal offences, with 3,000 offenders receiving a custodial sentence, served in one of Northern Ireland’s prisons, managed by NIPS. Similarly, around 3,000 offenders receive a supervised community sentence which, for adults, is managed by PBNI, which is also responsible for the post-custody supervision of around 500 adult prisoners upon their release each year.

3. Many individuals are reoffenders, trapped in a cycle of offending without making effective progress towards rehabilitation. DoJ’s most recent statistics show that 16 per cent of adult offenders reoffended within one year, with further analysis revealing that 46 per cent of adults who completed a custodial sentence reoffended within one year of release, whilst 29 per cent of adults subject to community supervision also reoffended.

4. Multiple factors, including age and gender, influence offending behaviour. People who encounter the justice system frequently tend to live disorderly lives and have significant mental health, alcohol and substance abuse issues. Homelessness, poor educational attainment and employment opportunities, and psychological issues also contribute. In addition, the unique context of Northern Ireland and the Troubles undoubtedly has a significant impact. These factors mean that managing and supporting the rehabilitation of these prolific offenders is complex and problematic.

5. Reoffending impacts significantly on society. A conservative estimate of its total annual economic and social cost in England and Wales is £18.1 billion, £16.7 billion of which relates to adult reoffenders. Similar estimates are unavailable in Northern Ireland (NI), but the figure is likely to be significant. These individuals and their families require access to effective support services to aid their rehabilitation and break their cycle of offending.

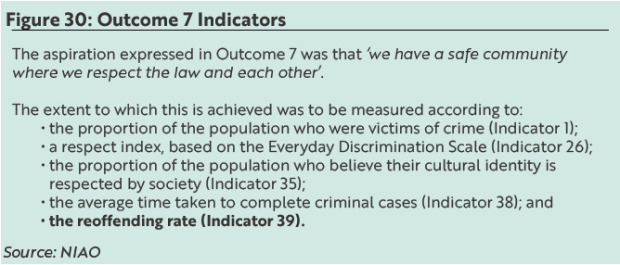

6. Reducing reoffending was first identified as a key Programme for Government (PfG) area within the draft 2016-2021 document (Outcome 7), with the reoffending rate included as one of the draft indicators (Indicator 39) intended to help monitor progress towards achieving this. Following the Executive’s collapse in January 2017, the Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS) assumed responsibility for developing Outcomes Delivery Plans (ODPs) to oversee the delivery of actions that supported the strategic direction set by the former Executive’s draft framework of outcomes. In relation to reoffending, the plans focused particularly on employment and delivering various `Problem Solving Justice’ (PSJ) initiatives.

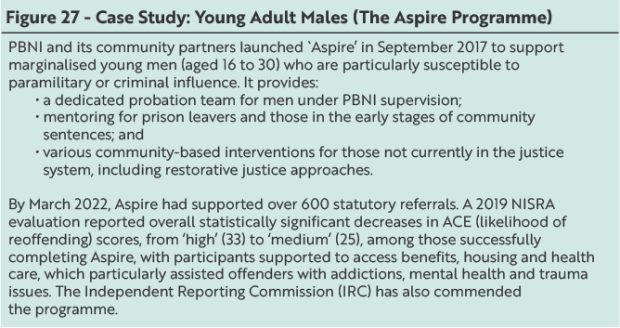

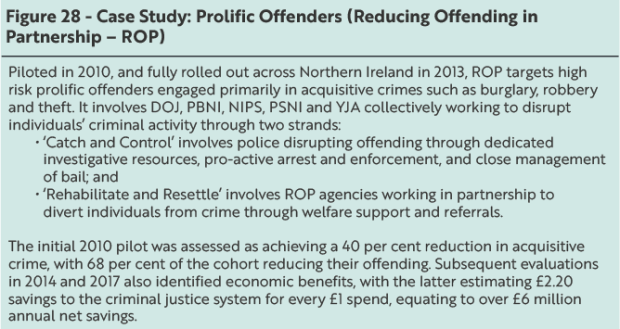

7. Our report identifies that, although there are some positive trends in offender numbers and reoffending levels, there continue to be systemic issues that impact on the ability of the justice system to rehabilitate a core group of prolific offenders. Undoubtedly, there have been other good developments, particularly in relation to some pilot projects which appear to have had positive impacts, but financial constraints and prioritisation of Covid recovery mean that they have not yet been fully evaluated and rolled out.

Key Findings

DoJ is aware of the key factors that impact on reoffending, and has been developing a greater focus on desistance and rehabilitation

8. The Department is well sighted on the principal factors that influence whether someone reoffends after an initial conviction. These include:

- family life and relationships;

- mental and physical health needs;

- substance and alcohol dependence;

- accommodation; and

- employment opportunities.

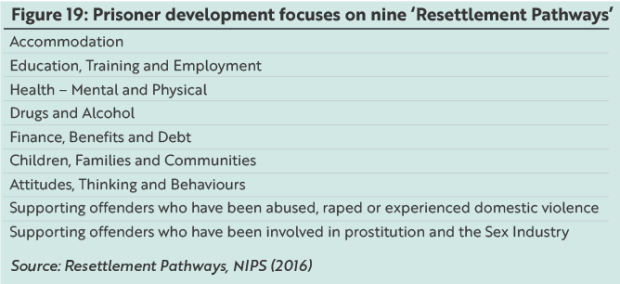

It has developed a range of measures over the last decade which seek to address these factors, and which place a strong focus on desistance (i.e. the premise that offenders can develop and change in the right circumstances) and rehabilitation.

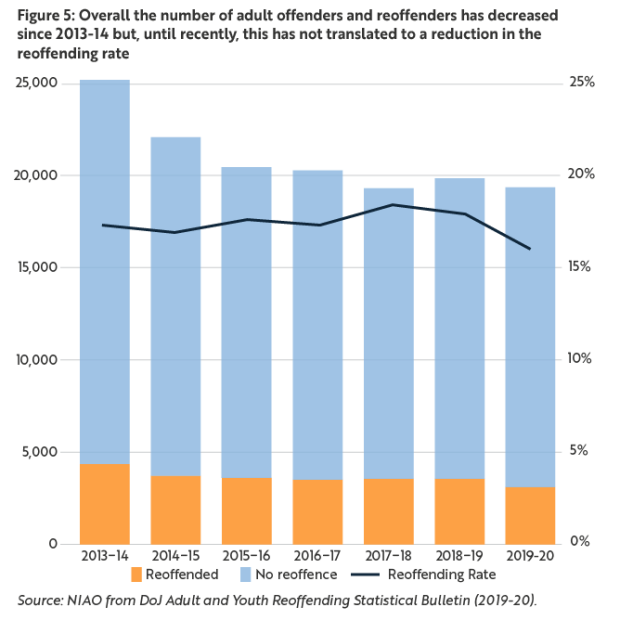

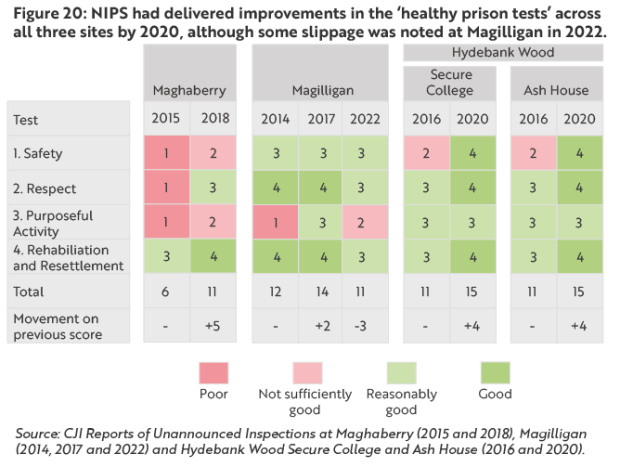

9. Evidence indicates that this approach has enjoyed a degree of success. Prisoner numbers are the lowest per population head in the United Kingdom (UK), and overall the number of offenders and reoffenders has reduced during the period 2013-14 to 2019-20, from 25,164 to 19,344 (23 per cent) and from 4,353 to 3,098 (29 per cent) respectively. Significantly, the most recent data for 2019-20, published in November 2022, revealed the lowest adult reoffending rate in NI (16.0 per cent) in almost a decade. Prior to this, the rate had stagnated at around 17 to 18 per cent. Whilst positive, some caution must be exercised over this recent trend as the COVID-19 pandemic may have influenced these statistics, due to reduced freedoms and the associated impact on court activity.

10. Further analysis would be significantly assisted by comparison of NI performance with other jurisdictions. However, this is not currently feasible, given differing measurement systems and techniques across the UK and the Republic of Ireland (RoI), and limited resources to undertake complex benchmarking work.

To address a remaining cohort of prolific offenders, enhanced strategic direction and accountability is required to advance the justice sector’s rehabilitation work

11. The draft PfG 2016-2021 was the first time that the Executive had established reducing reoffending as a key strategic area for government. In May 2017, DoJ subsequently established the Reducing Reoffending Strategic Outcomes Group (RRSOG) to provide strategic direction, oversight and monitoring of progress towards reducing reoffending rates to meet the PfG objective. Whilst a positive development, the RRSOG membership decided at an early stage that an updated cross-cutting or formal strategy for reducing reoffending was not required. A commitment to develop a short strategic narrative was also deferred in June 2019, in the absence of a functioning Executive at that time.

12. In our view, the decision not to develop an overarching strategy, aligned with the Department’s commitments under the draft PfG framework of outcomes, represented a missed opportunity to better address the issues which influence reoffending. This was heightened by weaknesses in the oversight and reporting arrangements for the group, in particular the absence of a formal link with the Criminal Justice Board (CJB), which includes representation from wider justice partners such as the judiciary, the NI Courts and Tribunals Service (NICTS) and the Public Prosecution Service (PPS).

13. The Department told us that its Strategic Framework for Reducing Offending, published in 2013, remains fit for purpose. However, in our opinion, it does not take account of significant strategic issues facing the justice system in more recent times, such as the high levels of short-term and remand prisoners. Further, monitoring against this Framework and a subsequent 2015 Desistance Strategy ceased in 2016, without formal evaluation of their implementation or effectiveness.

14. We consider that a more definitive strategic direction, identifying and prioritising the main actions, targets and expected outcomes, would likely have assisted further reductions in adult reoffending and left the statutory bodies better placed to target resources at the highest risk groups, which current statistics show to be young, male and prolific offenders of acquisitive crimes (burglary, robbery and theft). Going forward, a strengthened strategic approach to adult reoffending, and to this cohort in particular, is required if further reductions in the reoffending rate are to be achieved.

A stronger focus is also required on what reoffending costs society in NI and the expenditure the justice sector incurs on offender rehabilitation

15. Although the total annual estimated economic and social cost of adult reoffending in England and Wales is £16.7 billion (paragraph 5), DoJ is currently unable to estimate the equivalent costs for NI. In addition, whilst NIPS and PBNI incur approximately £16.1 million each year directly on interventions to support offender rehabilitation, DoJ is unable to disaggregate the wider indirect spend on reducing reoffending across the justice system. It is therefore not possible to produce a wholly reliable estimate of total expenditure on reducing adult reoffending.

16. This key gap in management information means the Department is unable to effectively assess, on an ongoing basis, the financial and strategic landscape it operates in, and whether the investment made by the justice sector in trying to reduce reoffending is a proportionate or sufficient response to the scale of the problem.

NI has high numbers of short-term and remand prisoners, but their access to rehabilitation and support services is limited

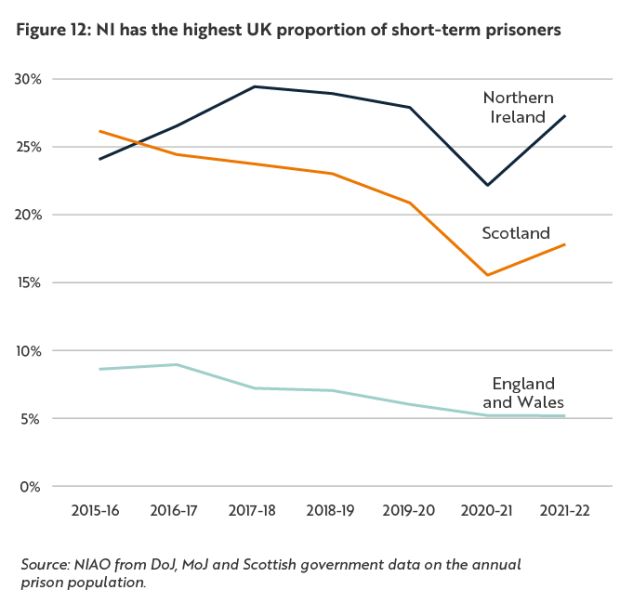

17. Over three quarters of custodial sentences bestowed by the courts are short-term (12 months or less), and around 27 per cent of the sentenced daily prison population in NI in 2021-22 comprised short-term prisoners. This significantly exceeds levels in Scotland and in England and Wales, which recorded approximately 18 per cent and 5 per cent respectively in the same period.

18. Short prison sentences can significantly disrupt offenders’ lives and their families and, crucially, can hinder rehabilitation through prisoners losing employment, housing or family contact. Offenders therefore often leave prison in poorer circumstances than when entering and, as a result, can be impacted far beyond the punishment intended by the court. Such offenders are entitled to access rehabilitation services whilst in custody, but the short period spent in prison often means there is limited scope for doing so. The consequences are clear, with short-term custodial sentences linked to higher reoffending rates. In 2019-20, 52 per cent of local custody releases who spent less than 12 months in prison reoffended. For supervised community orders, during the same time period, the corresponding reoffending rate was 29 per cent.

19.Criminal Justice Inspection Northern Ireland (CJI) has repeatedly commented that rehabilitation services for short-term prisoners have been at best inconsistent, and otherwise insufficient. To try and address gaps in support, NIPS introduced the Positive Outcomes for Short-Term Prisoners (POST) project in June 2016 in conjunction with NIACRO (an organisation which supports offenders). POST aimed to support purposeful activity and offered assistance across housing, literacy, employability and skills, with CJI stating that such a programme was “long-overdue”. However, a 2019 evaluation was unable to conclude whether it was effective in achieving its aim of encouraging desistance but found that the service was lacking in many aspects, indicating that there remains significant scope for improvement in support for this group.

20. Local short-term prisoners are not subject to post-custody supervision upon release and few support services are available to those transitioning to community life after a short-term sentence. Significant resettling difficulties can therefore be encountered, which increases the risk of reoffending, particularly in the three-month period post-release. Our research identified that ‘through the gate’ support is more advanced across the rest of the UK, where various initiatives have been operating since 2015.

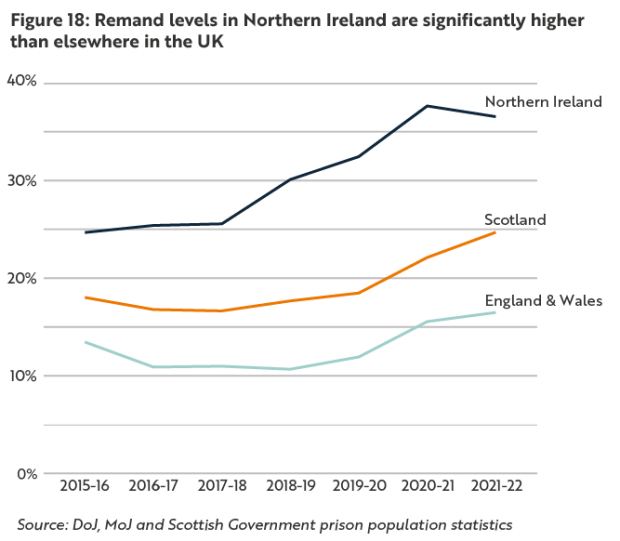

21. NI also has a far greater proportion of remand prisoners than other UK jurisdictions. The proportion of such prisoners has risen sharply locally, from under 25 per cent in 2015-16 to 37 per cent in 2021-22. This compares with 25 per cent in Scotland and 17 per cent in England and Wales. Issues with the legislative and policy framework in NI are likely contributing to these high numbers. Bail laws, for example, are not enshrined in a specific piece of legislation as in other UK jurisdictions, despite this being recommended by the Law Commission for Northern Ireland (NILC) in 2012, whilst repeated CJI recommendations for legally binding time limits to court cases, to help reduce avoidable delay and lower remand levels, also remain unimplemented.

22. The judiciary told us that inadequate bail support services, which would provide assurance that reoffending risks could be appropriately managed in the community, mean remand often becomes the preferred option when considering bail applications, as this assurance cannot be provided to the court at the time of the first appearance when bail is being considered. To further complicate matters, NI has no formal bail information scheme to provide judges with timely access to the information required to grant bail, including an individual’s circumstances and offending history. Again, both were recommended by the NILC in 2012. As a result, NI is currently significantly behind established bail practices in other UK jurisdictions.

23. NIPS, which is key to supporting rehabilitation, has limited scope to work with remand prisoners as, in many cases, they have not actually been convicted of any offence. A significant proportion, particularly those who are later convicted and released due to ‘time served’, therefore do not avail of rehabilitation support whilst in custody and this, combined with the effects of prison detention on accommodation, employment and family relationships, increases reoffending risks. The uncertainty surrounding remand release dates also conflicts with housing system processes and contributes to difficulties securing accommodation for discharge. This hinders access to other resettlement services requiring an address, including GP registration, opening new bank accounts or applying for benefits.

The Department has taken a number of initial steps to develop viable alternatives to short-term sentences and better address the needs of specific groups of reoffenders, but progress has stalled and meaningful work to address remand issues is at very early stages

24. Although formal assessment of the overall costs of short-term sentences and remand, compared to their alternatives (community orders and bail), has not been completed, both custodial options are accepted as being more expensive. Reducing overall numbers therefore has the potential to deliver significant cost savings, alongside improved reoffending outcomes.

25. In part recognition of this, the Department has introduced a range of ‘Problem Solving Justice’ (PSJ) pilots in recent years which aim to address the root causes of offending behaviour and provide meaningful and viable community-based alternatives for the judiciary when sentencing. The most significant of these is the Enhanced Combination Order (ECO), which was first introduced in October 2015 in the Ards, and Armagh and South Down court areas, and later extended to the North-West in October 2018.

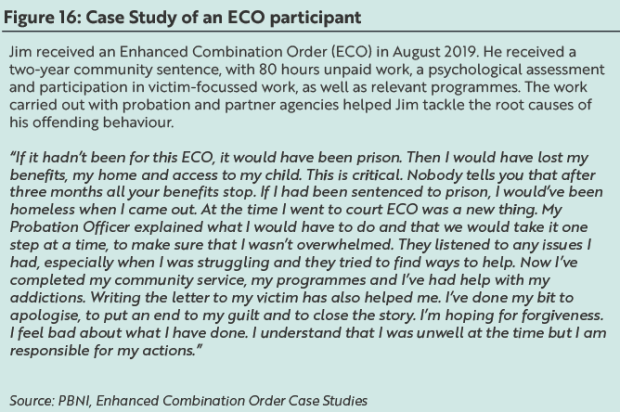

26. The ECO focuses on restorative practice, desistance and victims, with offenders also completing unpaid community work, and being referred for mental health, behavioural or family support, as appropriate. Non-compliance results in offenders being returned to court and potentially sentenced to custody. Three evaluations have reported positive findings on the pilot, including potentially significant annual economic benefits (£5.7 to £8.3 million) arising from full roll-out, but no further expansion has followed since 2018, primarily due to funding constraints. The Department now needs to assess the merit of full introduction across the remaining local court areas.

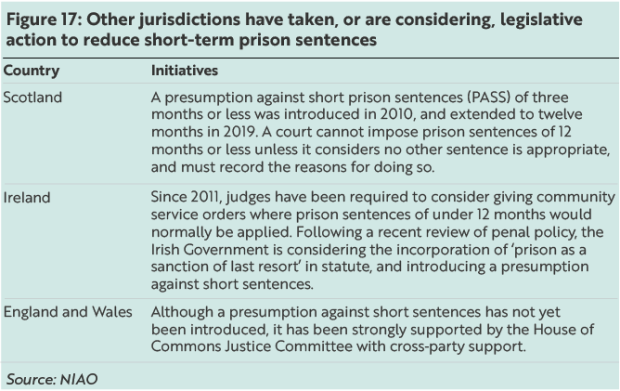

27. The Department announced a Sentencing Policy Review in mid-2016 which had the potential to help address issues around short-term sentencing. Following a process of planning and public consultation, in April 2021 it published a series of recommendations, highlighting strong support for the increased use of community disposals as an alternative to short-term prison sentences, and committing to consider in more detail a potential suite of new options. However, such change requires legislative action and, whilst preparatory work has commenced, it is a significant piece of work. Once this is completed and the legislation drafted, subsequent progress may be further impacted if there is not a functioning Assembly.

28. DoJ has not yet progressed several other PSJ initiatives to full implementation. The Substance Misuse Court (SMC) pilot was introduced in Belfast Magistrates’ Court at Laganside in April 2018. It places offenders on intensive treatment programmes, under court supervision, to specifically target drug and alcohol linked offending behaviour, with final sentencing reflecting their participation. Evaluations have indicated that those successfully completing the programme exhibited lower longer-term reoffending rates than those who did not, resulting in the SMC programme being embedded into the normal rostered business at Laganside from April 2021. Despite this apparent success, the development of a plan for wider roll-out, to be implemented in 2022-23, was not achieved due to budgetary constraints. In our view, however, relatively low participation and completion rates indicate that further consideration of the initiative is required to inform roll-out, including an assessment of its cost-effectiveness.

29. A Mental Health Court (MHC) pilot, which in theory would see offenders with mental health issues receive treatment while being subject to proceedings, was expected to deliver similar benefits but did not commence, with DoJ, in conjunction with the Department of Health (DoH), now currently trying to identify alternative approaches.

30. The Department told us that budgetary constraints and prioritisation of Covid recovery have prevented further progress in piloting, assessing, or rolling out these PSJ initiatives, and our review also noted similar problems with several other offender rehabilitation projects. DoJ now finds itself at an impasse, unable to confirm what the future of PSJ looks like, and whether these initiatives will be rolled out further.

31. In November 2022, the Department established a justice-wide remand working group to consider the options available to address the excessively high remand levels in NI. The increased focus on this area is a welcome development, albeit long overdue. Going forward, it will be incumbent on the Department to establish effective monitoring arrangements for the work of this group to ensure that the current momentum is maintained.

Improved cross-government working is needed to secure improvements across key desistance pathways including accommodation and mental health

32. Reducing reoffending is complex and involves many different parts of government. Preventive measures, such as stable family environments and accommodation, educational attainment, financial security and employment, and physical and mental health, all sit outside the scope of the justice system. The wide number of variables at play, many of which fall outside DoJ’s remit, and a continuously reducing justice budget, means the Department is operating in an extremely challenging environment.

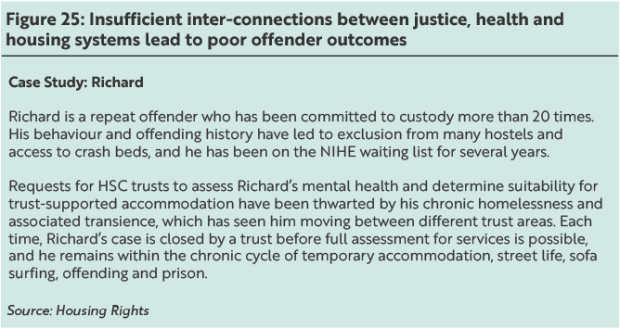

33. Although DoJ has led, or contributed to, some good collaborative initiatives aimed at improving offender outcomes across desistance pathways, particularly employment (paragraph 6), greater partnership working across government is required if real and sustainable change is to be delivered. Such arrangements had been envisaged by the draft 2016-2021 PfG but have fallen short because of alternative or competing priorities amongst partners within a severely pressured financial environment. Our stakeholder engagement highlighted that improvements are required, predominantly in areas such as accommodation and mental health, where poor or complex interfaces between these systems and justice act as significant barriers to resettlement.

34. Securing the required ‘buy in’ from other NICS departments to support collaborative working will prove difficult, given their own tight financial constraints. This is particularly the case given that improved cross-departmental processes, governance structures and reporting lines will also inevitably require significant upfront investment from the public purse. A new PfG, when introduced, may offer an opportunity to address some of these issues.

Work is required to develop an outcome measurement framework that underpins the PfG and the key justice-led indicators

35. Evaluation evidence indicates individual reoffending programmes and interventions can impact positively on outcomes, and this has perhaps contributed to the recent reduced reoffending rates (paragraph 9). However, in the absence of a well-defined strategic focus (paragraphs 11 to 14) which assesses the respective performance of these collectively, there is insufficient clarity on which measures are achieving greatest impact and need to be further supported, or which perhaps should be discontinued. This is important in maximising benefits in times of such finite resources.

36. Within DoJ, enhanced performance measurement and targets to monitor success in reducing the reoffending rate are clearly required. This view is shared by CJI, which has repeatedly highlighted the need for improved performance measures that indicate achievement of longer-term outcomes, to allow management to assess effectiveness of service provision and plan future delivery and resourcing.

37. Improved information will also enable the Department to understand more fully the impacts being generated from this aspect of its work. Currently, local systems do not capture all the data needed to measure wider outcomes, and progress is constrained by inadequate integration of systems and restrictions on data sharing. As paragraphs 15 and 16 noted, DoJ also does not know the cost of reoffending or what it spends trying to reduce it. These are key information gaps which mean that, overall, DoJ is unsighted on whether its investment in reducing reoffending is cost effective in delivering improved outcomes.

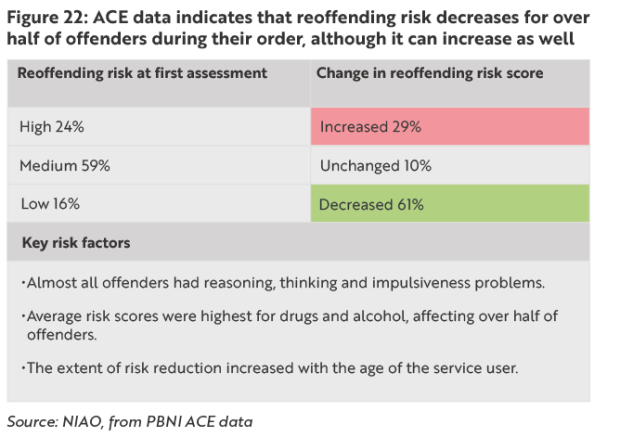

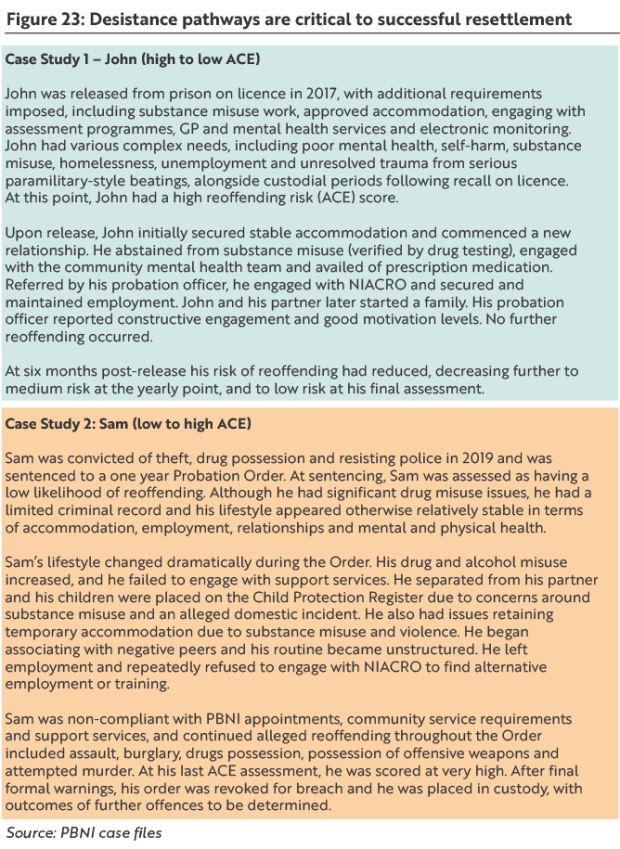

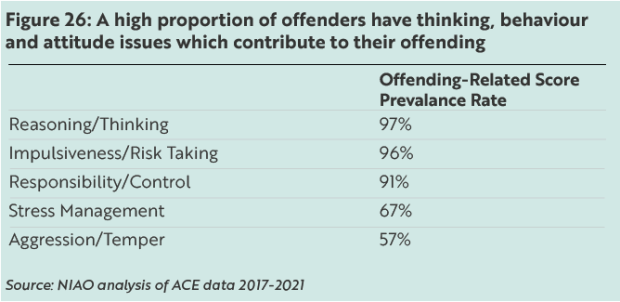

38. Existing information could also be strategically analysed better to inform policy and further decision-making. An important example of this is the Assessment, Case Management and Evaluation (ACE) methodology that PBNI uses to assess individuals’ reoffending risk. Whilst it is used to inform sentencing and case management at individual offender level, it is not routinely analysed cumulatively to assess the impact of specific interventions or better inform future strategy and resourcing. PBNI told us that it is currently exploring other, more sophisticated, risk assessment tools with potentially increased validity for this purpose.

Conclusions

39. Whilst the recent reduction in the reoffending rate may have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, wider longitudinal trends, such as falling offender and reoffender numbers, indicate that some of the current interventions may be having a positive impact. It should also be acknowledged that staff within the statutory organisations, and VCS partners, have continued delivering critical frontline services during the pandemic and against extremely challenging financial constraints.

40. However, meaningful comparison of reoffending rates with other UK and RoI jurisdictions is not feasible due to the various jurisdictions measuring and reporting outcomes differently, and more work is needed to identify the impact of specific programmes and understand which deliver the best outcomes in NI. Currently, DoJ could be better informed as to which of its initiatives are most successful in reducing reoffending and, in turn, which need to be prioritised, given the tight financial constraints it is working under. Implementation of key programmes and best practice has also been patchy, and NI is clearly some way behind the other UK jurisdictions in certain areas. To deal with a remaining cohort of prolific offenders and further improve performance, stronger strategic direction and focus is required.

41. Against this background, we conclude that scope exists for securing better value for money through the prioritisation of cost-effective measures which can more strategically target the key core reoffending groups.

Recommendation 1

The Department should carry out a review of its 2013 and 2015 strategic initiatives to ascertain how successful they have been in achieving outcomes. This learning should then be used by the Department to better define its strategic plan for reducing reoffending across key desistance pathways such as accommodation, employability and health, taking account of how cross-governmental collaboration can be strengthened to support justice aims in the short-term. It should also strengthen oversight and reporting arrangements to ensure successful delivery of these aims, including establishing formal links with the Criminal Justice Board (CJB). Finally, in the medium-term, and to align with any new Programme for Government agenda when published, the Department should take the lead in developing a cross-governmental strategy and action plan for reducing offending and reoffending.

Recommendation 2

The Department should devise an approach for estimating the economic and social cost of reoffending in Northern Ireland, drawing upon approaches used in other jurisdictions. It should then use this information to assess the adequacy of expenditure directed towards trying to reduce reoffending, and to help inform policy, strategy and potential invest-to-save initiatives going forward.

Recommendation 3

The Department should develop greater and more timely accessibility to rehabilitation initiatives to address the identified gaps in support for short-term prisoners. It should also review the adequacy of ‘through the gate’ support and, along with all relevant stakeholders, devise a solution(s) to better assist short-term prisoners’ transition to the community and resettlement in the early period post-release.

Recommendation 4

The Department, in conjunction with stakeholders, should complete its review of sentencing with the aim of providing the judiciary with viable community-based alternatives to short-term prison sentences. This work should consider how to fully roll-out the positively evaluated Enhanced Combination Order (ECO) pilot across Northern Ireland, and include plans to legislate for any new community disposals in the next NI Assembly mandate. The Department should also give policy consideration to the legislative options available for strengthening the principle of prison as a sanction of last resort for cases which may result in a short-term prison sentence.

Recommendation 5

The Department should assess the merit of introducing a bail information scheme and bail support services to help prompt a reduction in custodial remands. It should also evaluate the benefits of the numerous bail legislation and policy options available, whilst progressing work to consider alternatives, such as the expansion of the use of electronic monitoring.

Recommendation 6

The Department should consider approaches adopted elsewhere in the UK and RoI to address the range of problems posed by the high levels of short-term and remand prisoners, to assess if they could be used to provide solutions in Northern Ireland.

Recommendation 7

The Department should explore an increased use of the management information available to it. Working with the PBNI, this should include data from offenders’ risk of reoffending assessments, to monitor trends in client profiles and assess the impact of specific interventions on reoffending risk and subsequent outcomes. In support of this, PBNI should evaluate and conclude on the continued effectiveness of the Assessment, Case Management and Evaluation (ACE) methodology, in comparison to other risk assessment tools available.

Recommendation 8

The Department should appraise the overall participation and completion rates, and associated cost-effectiveness, of the Substance Misuse Court (SMC), to inform further roll-out. As plans to pilot a Mental Health Court (MHC) have not progressed, the Department should expedite identification of alternative problem-solving approaches to mental health issues for those in contact with the justice system. An invest-to-save approach should be adopted where initiatives such as these are assessed to deliver net economic benefits.

Recommendation 9

The Department, with support from the wider Executive, should identify meaningful, robust and realistic outcome-based performance measures to underpin future PfG indicators. This will require appropriate baselines and procedures for monitoring and reporting of performance. In support of this, the Department should further progress wider data collection and analysis to measure its impact in key areas, such as offenders’ accommodation, employability outcomes, or desistance from drugs and alcohol.

“We conclude that scope exists for securing better value for money through the prioritisation of cost-effective measures which can more strategically target the key core reoffending groups.” – Northern Ireland Audit Office

Part One: Introduction and Background

Introduction and Background

Reducing reoffending is a key objective of the criminal justice system

1.1 The justice system’s overarching purpose is to try and protect the public through effectively managing crime and offenders. Offenders encounter the system as it manages the consequences of their crime, and some will unfortunately repeatedly offend. Reducing crime levels and persistent offending to protect society and reduce the significant costs of criminality is a key government objective. A previous 2010 report estimated that society pays £2.9 billion each year to cover the cost of crime in Northern Ireland (NI).

1.2 Locally, around 17 per cent of adult offenders reoffend within one year, and repeat offenders commit almost three quarters of all proven offences. Domestic difficulties, financial issues or alcohol, drugs or mental health issues can foster repeat offender behaviour patterns, which impacts negatively across society. However, breaking this cycle is both challenging and complex.

1.3 Outcome 7 of the (draft) Programme for Government (PfG) 2016-21 included a priority to create a safer society. The PfG committed the Executive to collaboratively work with justice agencies, the voluntary and community sector (VCS) and educators to try and prevent offending and reoffending. Progress was mainly to be measured via reductions in crime prevalence and reoffending.

A number of justice organisations have significant roles

1.4 The Department of Justice (‘the Department’ or DoJ) has led on Outcome 7. Its mission is ‘working in partnership to create a fair, just and safe community where we respect the law and each other’. To support this, DoJ has established four main strategic themes, including challenging offending behaviour and rehabilitating offenders so that they do not reoffend.

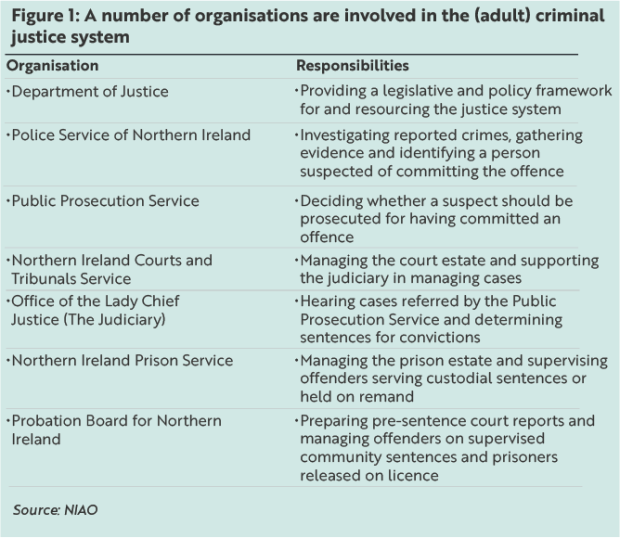

1.5The Department’s Reducing Offending Directorate (ROD) oversees policy and strategy development on reducing offending, principally through measures which support diversion, intervention, rehabilitation and joined-up custodial services. However, adult offenders encounter other criminal justice organisations across the system (Figure 1).

The criminal justice process can deliver a range of outcomes

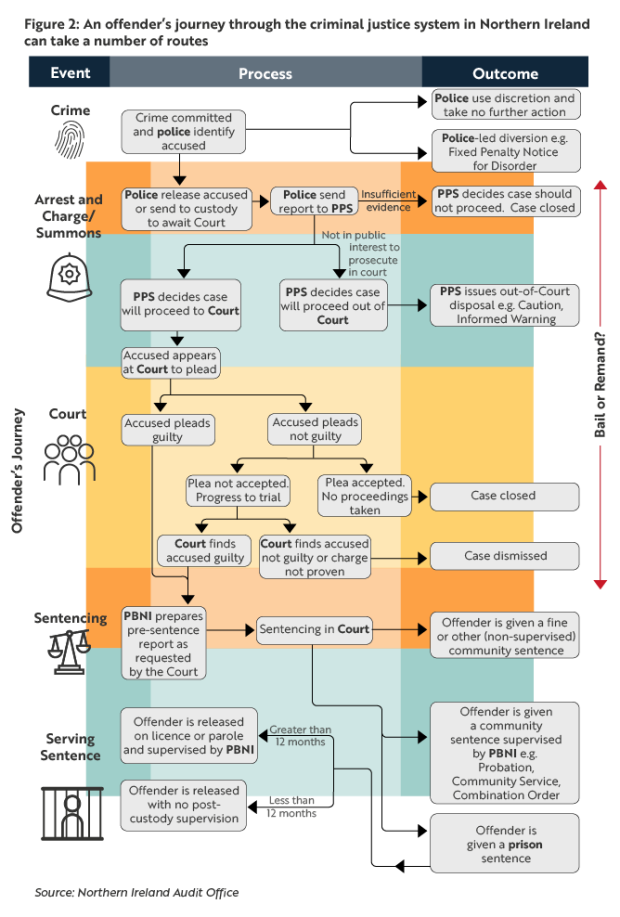

1.6 The PSNI investigates around 100,000 recorded crimes each year. Two thirds of these will not result in a charge due to evidential problems, or a suspect not being identified. Figure 2 shows how the criminal justice process in Northern Ireland operates.

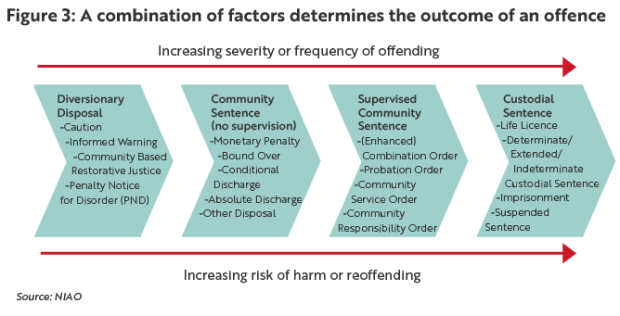

1.7 For cases that do progress following PSNI investigations, various factors determine how these crimes are disposed (Figure 3) including:

- nature and severity of the offence;

- perceived risk to the public;

- impact on the victim; and

- the offender’s personal circumstances, including criminal history and assessed reoffending risk.

1.8 Where an accused has been identified for a minor offence, both the PSNI and Public Prosecution Service (PPS) can issue a ‘diversionary disposal’. More serious offences, for which the PPS determines there is sufficient evidence and prosecution is in the public interest, are tried in court. The local criminal justice system handles around 35,000 disposals of varying types annually, around 80 per cent of which are disposed at court.

1.9 The impact of COVID-19 saw court activity reduce during 2020 as sittings were suspended and the justice system’s capacity was seriously disrupted. Conversely, out-of-court disposals rose significantly due to new COVID-19 offences being dealt with through Penalty Notices for Disorder (PNDs). In 2021, court activity returned to pre-pandemic levels.

1.10 Following a court conviction, offenders may serve a custodial sentence in a NIPS prison, a community-based sentence supervised by PBNI, or a combination of both. These organisations deliver services and support to offenders to try and prevent reoffending. On average, approximately 3,000 custodial sentences (not including those suspended) are imposed annually (around 13 per cent of total court convictions), with a similar number of supervised community sentences imposed. However, roughly 14,000 convicted offenders each year (around 60 per cent) receive a community-based disposal without supervision, primarily a fine. Figure 4 provides a typical breakdown of the outcomes of recorded crimes.

The number of offenders and reoffenders has reduced notably but the reoffending rate has not shown comparable improvement

1.11 PfG Outcome 7 is underpinned by a specific Key Indicator 39 which aspires to a reduction in the reoffending rate, although a target for the level of reduction in the reoffending rate has not been set. We discuss this issue further in Part Five. Effectiveness in delivering Outcome 7 is mainly measured through the ‘one-year proven reoffending’ methodology, which tracks offending behaviour for twelve months after someone has been through the criminal justice system.

1.12 Between 2013-14 and 2019-20, the total number of adults who received a non-custodial court disposal, a diversionary disposal or who were released from custody each year fell by 23 per cent from 25,164 to 19,344 and those who reoffended fell by 29 per cent from 4,353 to 3,098 (Figure 5), resulting in a reduction in the reoffending rate from 17.3 per cent to 16.0 per cent over this period. Despite this positive outcome, the latest statistics for 2019-20 reflect the impact of the pandemic on individuals’ freedoms and behaviour, alongside disruption to the courts system (paragraph 1.9) and, consequently, the number of reconvictions recorded. Prior to this, the reoffending rate had shown a slight increase since 2013-14 (to 17.9 per cent in 2018-19).

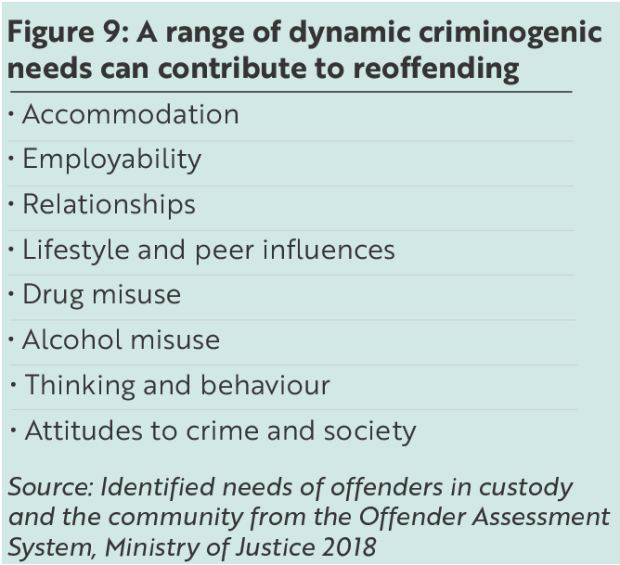

Multiple ‘criminogenic needs’ influence reoffending behaviour

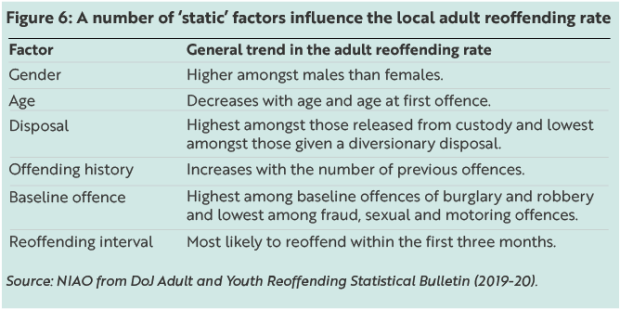

1.13 Various individual or social risk factors, or ‘criminogenic needs’, are associated with reoffending risk, and can be categorised as either `static’ or `dynamic’. Static factors include criminal history, age and gender and can be routinely analysed for trends (Figure 6). However dynamic factors, such as accommodation, employment, relationships and drug misuse, are amenable to change, and measuring their impact is difficult due to their complex interrelationships. Reoffending is typically influenced by a combination of these factors. Policy makers must therefore understand such influences to target interventions at the highest risk groups.

Offending and reoffending rates are highest amongst young males

1.14 Locally, males account for over 80 per cent of court prosecutions and 96 per cent of the average daily prison population. Likewise, males dominate the overall offending cohort (80 per cent) and exhibit higher reoffending rates; approximately 19 per cent of adult males reoffend annually compared to around 12 per cent of females.

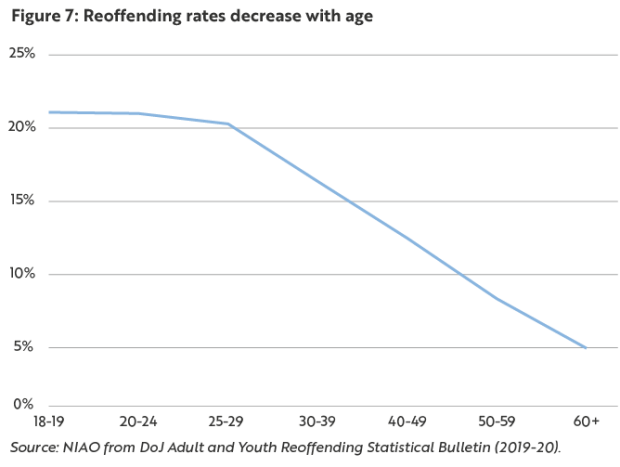

1.15 Younger adults are also a high-risk group. While adults aged under 40 comprise around a quarter of the local population, they represent over two thirds of both court prosecutions and the prison population. Reoffending is highest for those aged 18-19 (around 21 per cent in 2019-20) but progressively reduces to around 5 per cent for those aged 60 and above (Figure 7). Similarly, reoffending is highest amongst those who initially offend at a young age.

Criminal history and the nature of the baseline offence strongly influence reoffending patterns

1.16 Persistent or ‘prolific’ offending is a key problem in NI. The latest reoffending statistics (2019-20) show that two thirds of the adult cohort had a criminal history, with more than a quarter having committed over ten previous offences. Of those who then went on to reoffend within the twelve-month observation period (3,098 adults), two thirds committed multiple reoffences, ranging from two to 32 crimes. In total, over 10,000 proven reoffences were recorded i.e. more than three per reoffender. The Department told us that this ‘hard-to-reach’ group of prolific offenders is inhibiting further or faster reductions in the overall reoffending rate (paragraph 1.12).

1.17 Those who commit acquisitive crimes such as burglary, robbery or theft are also most likely to reoffend, whilst individuals committing fraud, motoring or sexual offences exhibit low reoffending rates (Figure 8).

Reoffending is highest among those released from custody, and is most likely to occur within the first three months after discharge

1.18 Evidence also shows that those serving custodial sentences have the highest reoffending rates. For 2019-20, the respective one-year adult reoffending rates were:

- released from custody - 46 per cent;

- non-custodial disposal with community supervision - 29 per cent;

- non-custodial disposal without supervision - 15 per cent; and

- diversionary disposal - 12 per cent.

1.19 Almost half of reoffenders do so within the first three months of being discharged from custody, receipt of non-custodial disposal or diversionary disposal. Approximately one fifth will do so within the first month.

Offenders have a higher prevalence of dynamic risk factors associated with reoffending

1.20 Dynamic criminogenic needs (Figure 9) also contribute towards people initially committing crimes and contact with the criminal justice system can exacerbate these, bringing repeated offending. Ministry of Justice (MoJ) studies indicate that those with a higher prevalence of need have the greatest reoffending risk, and that levels of need amongst offenders vary with static factors such as gender, age and sentence type. In addition, some factors are particularly associated with certain types of crime, for example, drug misuse is closely linked with acquisitive crimes such as shoplifting, and alcohol misuse with violence. Learning disability, mental health issues and low psychosocial maturity can also affect how offenders respond to support for their criminogenic needs.

1.21 Dynamic risk factors are reflected within the profile of the local custodial population, as indicated by an analysis of Prisoner Needs Profiles created in 2022:

- 74 per cent left school at age 16 or under and 32 per cent had no qualifications;

- 67 per cent were receiving social security benefits;

- 66 per cent reported having used drugs at some stage in their life;

- 53 per cent had children;

- 33 per cent had some form of contact with mental health services prior to custody;

- 30 per cent had experienced low mood or depression;

- 21 per cent considered themselves to have learning difficulties or disabilities; and

- 12 per cent were homeless or were living in a hostel prior to custody.

1.22 Paragraphs 1.14 to 1.21 outline how reoffending is very high amongst specific groups, together with key factors which influence reoffending behaviour. If local reoffending levels are to be further reduced, the key statutory stakeholders must take full consideration of the wealth of information available, and target strategies and interventions towards these groups.

Scope and Structure

1.23 Our report considers how effectively DoJ has worked with the key justice organisations to reduce adult reoffending. Younger offenders have been excluded from the scope of the review as they were covered separately in our 2017 report.

1.24 We examined both custodial and community settings to determine how different parts of the justice system work individually and collectively to develop, implement and assess initiatives aimed at diverting offenders from crime.

1.25 Many societal problems that trigger offending (paragraph 1.20) are not within the remit of the justice system. These include accessibility of health services, poverty levels, social deprivation and unemployment, a lack of affordable and suitable housing and low educational attainment. As such, primary prevention of offending best sits outside the justice system, delivered through good quality universal services, with targeted additional support for high-risk individuals and groups, supported by commitment from the health and education sectors and other partners. Our report only considers, however, how the justice system seeks to address these wider factors in managing offenders within their remit.

1.26 The report examines:

- the Department’s approach to reducing reoffending (Part 2);

- the key strategic challenges faced (Part 3);

- the services provided to help the rehabilitation of offenders (Part 4); and

- assessing performance and measuring outcomes (Part 5).

1.27 Our review used a range of investigative and research methods (Appendix 1).

Part Two: The Department’s approach to reducing reoffending

The Department’s approach to reducing reoffending

Reducing reoffending has been a longstanding objective of the justice system, with an evolving approach focused on desistance and rehabilitation, but a more clearly defined strategic direction could have produced better results

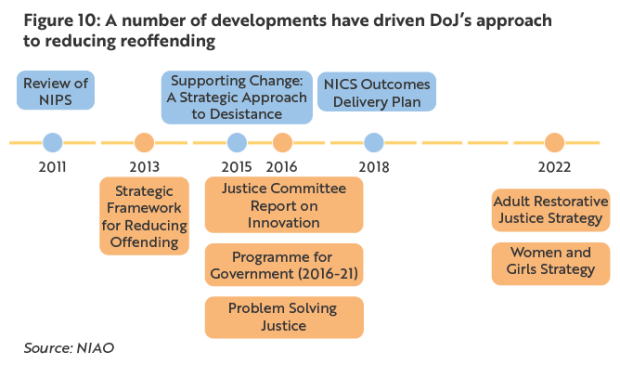

2.1 A key objective of the justice system is to rehabilitate offenders so that they do not reoffend having completed their sentence. Stakeholders widely acknowledge that achieving lasting reductions in reoffending requires significant investment and joint working across the justice system, alongside other government and voluntary sector bodies. However, achieving this objective is challenging, requiring the justice sector to clearly identify the change it can effect, and where it requires broader input. The extent to which DoJ has clearly defined, monitored, and economically quantified this is unclear, with its approach having evolved in response to various related developments across the justice system and wider government since 2011 (Figure 10).

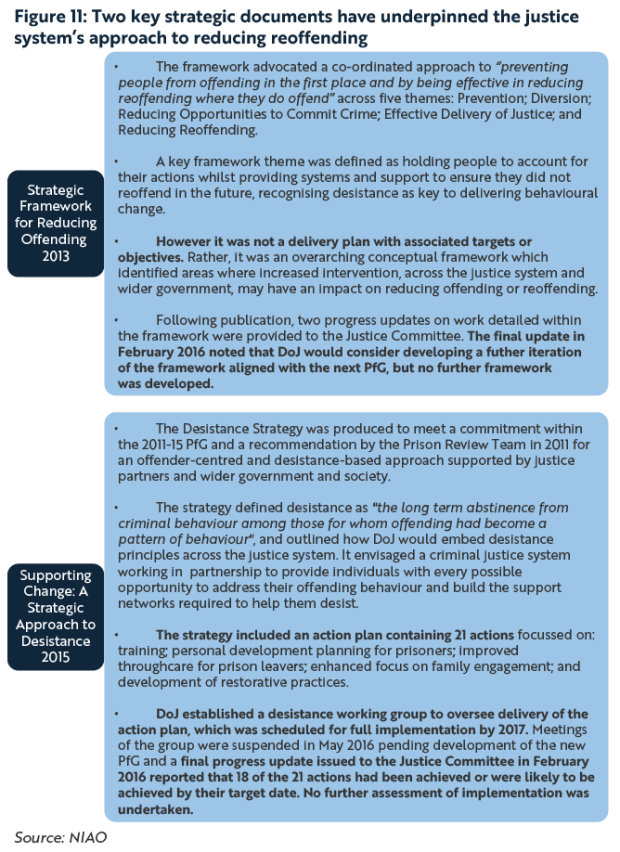

A Strategic Framework and Desistance Strategy have predominantly guided the Department’s work in this area, but their overall effectiveness has not been determined

2.2 Two key documents have guided DoJ’s strategic direction for reducing reoffending over the past decade: a 2013 Strategic Framework for Reducing Offending and a 2015 Desistance Strategy (Figure 11). In line with considerable evidence supporting the approach, both promoted the concept that punitive measures alone would not sustainably reduce reoffending, and that a focus on enabling offenders to reform and desist from crime was also needed.

2.3 Although both documents cited reduced reoffending as an objective, in our view, neither represented an overarching strategy or measurable strategic plan for delivering this. Whilst the Strategic Framework was a significant piece of work, which envisaged outcomes such as a reduction in reoffending and fewer first-time offenders, it did not include a delivery plan with associated targets or objectives to achieve these. Rather, it represented a conceptual narrative aimed at promoting joined-up working and highlighting wider governmental action that should contribute to tackling the underlying causes of offending behaviour. Positively, the Desistance Strategy, which was solely justice-focussed setting out how DoJ would deliver change through applying desistance principles across the system, did contain a detailed action plan, however it did not include arrangements for evaluating its impact.

2.4 Progress reporting indicated that implementation of the desistance action plan had some success, with the final update (February 2016) reporting that 18 of the 21 actions had been achieved or were likely to be achieved by their target date. Part Four examines the outworking of some of these actions, including introducing personal development planning for prisoners. However, evidence underpinning the progress reported for some other key actions is limited. For example, developing an engagement plan for work with other departments was reported as ‘likely to be achieved by target date’ of March 2016 but we saw no evidence that such a plan was produced. Likewise, work to improve data relating to the effectiveness of reducing offending interventions was assessed as ‘complete’, based on an initial analysis of one VCS employability programme. This work did not develop any overall means of data capture or analysis, nor identify suitable measures or indicators to support DoJ in measuring progress, as per the initial intention. The wider issues of outcomes and performance measurement are further examined at Part Five.

2.5 Monitoring of both the Framework and Desistance Strategy ceased in 2016. Their final implementation was not formally appraised and, consequently, it is unclear whether their objectives were fully achieved, prior to DoJ embarking on new work under the subsequent PfG.

Although the 2016-21 draft Programme for Government increased the focus on reducing reoffending, DoJ did not establish a strategy to support it

2.6 The 2016-21 (draft) PfG framework, and subsequent NICS Outcomes Delivery Plans (ODP), established reducing reoffending as a key focus area across government within Outcome 7 (paragraph 1.3), led by DoJ, with progress to be measured mainly via a reduction in the reoffending rate (Indicator 39). To provide strategic direction, oversight and monitoring of progress towards this objective, DoJ established a Reducing Reoffending Strategic Outcomes Group (RRSOG) in May 2017, with membership comprising senior DoJ, NIPS, PBNI, YJA, and PSNI officials.

2.7 Although facilitating partnership working across several key justice sector partners, the membership decided in April 2018 that a formal strategy for reducing reoffending was not required. A commitment to develop a short strategic narrative was also later deferred in June 2019 in the absence of a functioning Executive. Instead, DoJ has relied upon the NICS ODPs, and strategic priorities noted within Corporate and Business Plans, to drive work in this area. These, however, do not specifically set out how the justice system has prioritised areas for focus and investment in reducing reoffending, or what the various statutory stakeholders or initiatives are expected to contribute to achieve this objective.

2.8 The Department has confirmed that the overarching approach within the 2013 Strategic Framework (paragraphs 2.2 to 2.3) remains fit for purpose. However, in our view, it is unclear how a framework setting out the criminal justice landscape a decade ago, and its interplay with wider governmental and societal initiatives at that time, remains current today. For example, it does not take account of more recent significant developments discussed later in this report, such as rising levels of short-term and remand prisoners, and an increasing prevalence of mental health issues.

2.9 As a result, we consider that there has been insufficiently robust strategic direction for developing, monitoring and prioritising collaborative work to reduce reoffending, particularly in recent years. Consequently, there remains inadequate evidence of what works well locally, and the justice system is poorly sighted on outcomes or value for money achieved from its investment in this area. Such information is required to inform the development of a formal reoffending strategy or plan, which clearly outlines the work required to deliver measurable outcomes and benefits.

2.10 In England and Wales, by comparison, Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) published Regional Reducing Reoffending Plans in 2021, setting out the most important activities each region is prioritising to reduce reoffending between 2022-25. These plans are supported by specific targets and objectives, across four areas:

- training skills and work;

- drugs and alcohol addiction;

- family, accommodation and readjustment to society; and

- public security through engagement and compliance.

More recently, DoJ has focussed on several discrete strategic areas, which may help reduce reoffending, but funding constraints threaten their implementation

2.11 In recent years, DoJ has focussed on a number of discrete strategic areas, which it expects will further advance rehabilitation efforts and consequently reduce reoffending, however, in the absence of an overall reoffending strategy (paragraphs 2.7 to 2.9), their anticipated contribution to the objective is unclear.

2.12 Firstly, within the June 2018 and December 2019 ODPs (paragraph 2.8), DoJ committed to introduce `Problem Solving Justice’ (PSJ) initiatives, reflecting recommendations from a 2016 Committee for Justice report, which called for more innovative ways of addressing the root causes of offending. Between 2019-20 and 2022-23, DoJ has prioritised around £8.2 million of budget to allocate to partners across justice and wider government, to develop, pilot and evaluate a portfolio of PSJ projects within a five-year plan. Whilst some projects, such as Multi-Agency Support Hubs, aim to support vulnerable people through early intervention and prevention, others place offenders in tailored programmes under court supervision, including:

- Enhanced Combination Orders (ECOs), which provide judges with a more intensive community sentence option, instead of a short-term prison sentence;

- Substance Misuse Courts (SMCs), which place offenders on intensive treatment programmes, with final sentencing taking account of participation; and

- Mental Health Courts (MHCs), which aim to ensure that offenders with mental health issues can access treatment while being subject to proceedings.

2.13 Progress in implementing these specific projects is assessed in greater detail in Parts Three and Four. The five-year plan set out an implementation schedule and multi-year evaluation programme for each initiative, including a review of the wider PSJ Programme in 2022-23 and an overall Economic Impact Assessment in 2024-25.

2.14 Delivery of individual PSJ initiatives is subject to affordability and business case approval. However, given the considerable financial pressures and reducing budgets that the Department currently faces, further advancement of the PSJ programme has been significantly impacted, with its component initiatives at various stages of development and evaluation. DoJ estimates that further expansion of PSJ will cost an additional £6.3 million by 2024-25, meaning it is unclear whether any further progress will be achieved. An overall review of the programme is now required to inform the future strategic direction and priority of this work.

2.15 In addition, two further DoJ strategies, launched in March 2022, aim to supplement current approaches to rehabilitation:

- A Restorative Justice Strategy aims to increase the use of restorative practice within the adult justice system and across all types of disposals. This followed recent developments within youth justice and recommendations within various reports which advocated its use. The strategy envisages that adding restorative practice to current rehabilitation work will help contribute to reduced reoffending, whilst also addressing victims’ needs.

- Although females account for around a fifth of offenders (paragraph 1.14), their contact with the justice system can have a profound and lasting impact on them and their families. A Strategy for Women and Girls was therefore developed, aimed at introducing gender-responsive prevention and early intervention approaches to tackle underlying issues and provide tailored support in, and beyond, custody.

2.16 Stakeholders view both initiatives as having potential to deliver real change, albeit somewhat overdue. However, significant financial constraints mean resourcing to implement the associated action plans has not yet been identified. Delivery is again subject to individual affordability or identification of innovative funding sources, and considerable uncertainty therefore also exists over whether these strategies will proceed as envisaged.

Alongside better strategic planning for reducing reoffending, accountability structures for monitoring performance require improvement

2.17 Although RRSOG initially reported progress against Outcome 7 of the ODP to The Executive Office (TEO), formal progress monitoring by TEO ceased following the revised ODP published in December 2019, as work had commenced to develop a new PfG which would, in theory, supersede it. Although consulted upon in 2021, a new PfG was not established prior to the subsequent collapse of the Executive in February 2022. No alternative mechanism was established for reporting on reducing reoffending by RRSOG.

2.18 The RRSOG has had no role in overseeing the more recent PSJ range of initiatives (paragraphs 2.12 to 2.14), which might potentially deliver tangible reoffending benefits. Furthermore, its membership has not included wider justice partners such as the judiciary, NICTS or PPS, whose involvement might have offered broader insight and perspective on issues impacting on reoffending, for example sentencing policy and practice. The Criminal Justice Board (CJB), comprising such representatives, has oversight of criminal justice in NI and could potentially provide valuable input to the RRSOG’s work, but no formal relationship between the two groups has been established.

2.19 DoJ told us that it is currently evaluating RRSOG’s terms of reference to help identify its future oversight priorities. It is important that this review also considers how the strategic direction (paragraphs 2.7 to 2.9) and accountability arrangements for reducing reoffending can be enhanced, including defining:

- DoJ’s priority work areas and their expected contribution to an overall reduction in the reoffending rate, including how this will be measured;

- the anticipated costs and benefits of achieving improvement;

- areas where improved cross-governmental collaboration is required to deliver better rehabilitation and reoffending outcomes; and

- a clear reporting structure for the group, such as potentially establishing formal links to the CJB and PSJ delivery teams, and for regular progress and performance reporting to DoJ.

Recommendation 1

The Department should carry out a review of its 2013 and 2015 strategic initiatives to ascertain how successful they have been in achieving outcomes. This learning should then be used by the Department to better define its strategic plan for reducing reoffending across key desistance pathways such as accommodation, employability and health, taking account of how cross-governmental collaboration can be strengthened to support justice aims in the short-term. It should also strengthen oversight and reporting arrangements to ensure successful delivery of these aims, including establishing formal links with the Criminal Justice Board (CJB). Finally, in the medium-term, and to align with any new Programme for Government agenda when published, the Department should take the lead in developing a cross-governmental strategy and action plan for reducing offending and reoffending.

Insufficient clarity on the economic and social costs of reoffending in NI, alongside public expenditure allocated to address it, further limits DoJ’s ability to plan and evaluate its work

2.20 A conservative estimate of the total annual economic and social cost of reoffending in England and Wales is £18.1 billion, £16.7 billion of which relates to adult reoffenders. This spans three broad categories of costs identified by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ):

- Costs in anticipation of crime (£2.6 billion): costs incurred by individuals and businesses to protect them from crime e.g. crime detection and prevention, defensive equipment, insurance;

- Costs as a consequence of a crime (£10 billion): direct costs to individuals and services arising from crime, including: human and emotional costs (such as physical or psychological injury); value of property stolen; lost output at work; and NHS and victim services costs; and

- Costs in response to crime (£4.1 billion): costs associated with police investigations, court processes, and prison detention.

2.21 By comparison, very little information is available on reoffending costs in NI, either incurred directly by the justice system or in terms of how wider society is impacted. However, based on the MoJ estimates, these costs are likely to be substantial, highlighting why government needs to support effective reducing reoffending initiatives.

2.22 Limited information is also available on expenditure targeted at reducing reoffending. For example, DoJ cannot identify how much, overall, criminal justice organisations spend in delivering the PfG / ODP commitments, or its total resource costs incurred on policy and strategy development and implementation. It told us that there is no defined budget for this work, with resources derived through separate policy areas and as part of specific programme budgets. The various strategies and initiatives which contribute to, but are not always necessarily directly aimed at, improved reoffending outcomes make it difficult to accurately attribute expenditure to this area.

2.23 DoJ further explained that disaggregating indirect expenditure would present significant challenges not only for it, but for the NICS generally and, if possible, the potential to analyse its specific impact would be inhibited by causality, given that many of the factors affecting reoffending such as accommodation, employment and healthcare are outside the Department’s control. DoJ believes that doing so is therefore not practical nor possible and, as a result, we could not identify a wholly reliable estimate of how much the local justice system spends on trying to reduce reoffending and support offender rehabilitation.

2.24 NIPS and PBNI, however, provided financial information which identified their direct budget allocation, i.e. funding directed specifically to activities that support rehabilitating and resettling offenders in their care, at around £16.1 million in 2022-23 (Appendix 2). Whilst incomplete information on the economic and social impact of reoffending for NI society (paragraph 2.21) makes it difficult to assess the adequacy of funding directed towards addressing the issue, £16.1 million may represent relatively modest support. Assessing costs and benefits facilitates evidence-based decisions that enable limited resources to be targeted cost-effectively. However, to properly evaluate this in overall terms, and at individual programme level, the key statutory bodies require better information on total costs arising from local reoffending.

Recommendation 2

The Department should devise an approach for estimating the economic and social cost of reoffending in Northern Ireland, drawing upon approaches used in other jurisdictions. It should then use this information to assess the adequacy of expenditure directed towards trying to reduce reoffending, and to help inform policy, strategy and potential invest-to-save initiatives going forward.

“Very little information is available on reoffending costs in NI, either incurred directly by the justice system or in terms of how wider society is impacted. However, based on the MoJ estimates, these costs are likely to be substantial, highlighting why government needs to support effective reducing reoffending initiatives.” – Northern Ireland Audit Office

Part Three: The key strategic challenges

The key strategic challenges

A significant proportion of prisoners have limited access to rehabilitation services

3.1 A range of rehabilitation services are provided within custodial and community settings for those who have offended. We outline and evaluate these in Part Four. However, a significant proportion of the prison population have limited access to such rehabilitation initiatives, namely short-term prisoners and those being held on remand, and evidence suggests that this has a significant impact on the potential for reoffending.

Northern Ireland has the lowest UK prison population but a comparatively high proportion of short-term prisoners who receive little rehabilitation

3.2 Determining an appropriate sentence for a convicted offender is the responsibility of the independent judiciary. In NI, legislation sets maximum, and sometimes minimum, penalties for offences, but judges still have considerable discretion over sentencing, meaning they have to carefully consider the circumstances of each case to determine a suitable response.

3.3 For serious offences, prison is often necessary to provide punishment and protect the public, but evidence suggests that prison itself can be criminogenic, given that its environment, culture and regime can increase the likelihood of an offender’s further involvement in criminal behaviour. Alongside potentially damaging effects of imprisonment on personal lives, such as weakening social ties, creating stigma, and losing employment or housing, there are clearly potential questions over its general effectiveness. However, in overall terms, NI has the lowest prison population in the UK, with 96 prisoners per 100,000 population in 2020-21, comparing favourably with 173 in England and Wales and 162 in Scotland.

3.4 Despite this, a much greater proportion of local adult prisoners are serving short-term sentences (less than one year). These significantly disrupt the lives of offenders and their families but offer little rehabilitative support because of the limited time available to do so. Such offenders therefore often leave prison in poorer circumstances than when entering, and are impacted far beyond the punishment intended by the court for the severity of the crime committed. Over three quarters of sentenced offenders committed into custody in NI during 2021-22 (513 individuals) received a short custodial sentence, and those prisoners constituted just over one quarter of the daily average sentenced prison population over the year. Available information suggests the rest of the UK has a much lower ratio of short sentence prisoners (Figure 12).

Short-term prisoners are a significant challenge for NIPS and are more likely to reoffend than offenders given less costly community disposals

3.5 Short-term prisoners present significant challenges to NIPS, particularly given the administrative and financial impact of a high turnover of individuals within its prisons. Many have numerous previous convictions and higher criminogenic needs but, in NI, those serving sentences of under one year spend an average of four months in prison, indicating the scarce time NIPS has to prepare prisoner plans and commence any form of meaningful rehabilitative work. CJI highlighted clear challenges around this issue in 2018.

3.6 Prioritisation of resources towards longer sentence prisoners, who must demonstrate reduced reoffending risk before release, means short-term prisoners are also often low down rehabilitation waiting lists. More recently, increased backlogs and waiting lists arising from Covid mean short-term prisoners are increasingly unlikely to receive support. However, NIPS cannot quantify the extent of this problem.

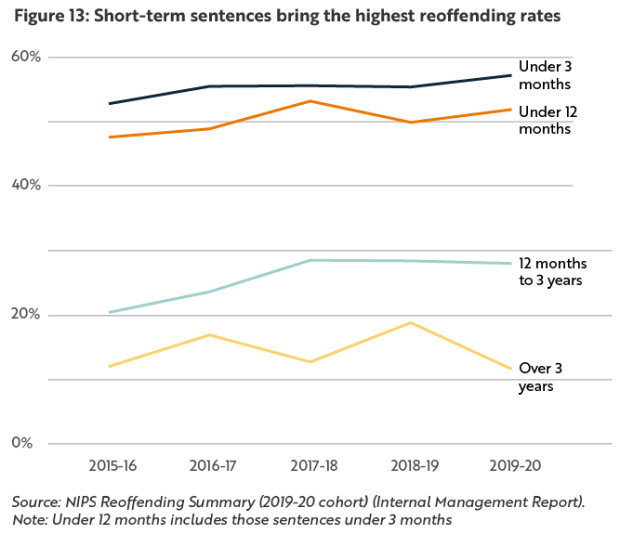

3.7 As a result, short-term prison sentences are linked to high rates of reoffending. MoJ reports in 2015 and 2019 found that prison sentences of under twelve months correlated with higher proven reoffending rates (by 4 percentage points) than community orders and suspended sentences, and local reoffending data highlights similar trends. In 2019-20, 46 per cent of adult custody releases in NI reoffended, compared with 29 per cent for supervised community orders (paragraph 1.18). More significantly, longstanding patterns show highest reoffending rates amongst prisoners serving the shortest sentences. Each year, around half of those released following a sentence of under 12 months reoffend, increasing to 57 per cent (2019-20) for those serving under 3 months. In contrast, around 12 per cent of those serving over three years reoffend (Figure 13).

3.8 Although the risk profile of an offender may be linked with their likelihood of reoffending, the weight of evidence suggests that non-custodial disposals are generally more effective in rehabilitating offenders and reducing reoffending than prison sentences, particularly when compared with short-term sentences. Community orders can, in appropriate circumstances, penalise offenders without extensively disrupting lives. For example, they can restrict offenders’ liberty whilst serving their sentence under supervision, offer greater access to rehabilitation services, and often ensure engagement in reparative activities. Community orders are also significantly less expensive, as indicated by NIPS’ estimated cost per prisoner place of £44,868, compared with PBNI’s estimated annual cost per supervised community order of between £1,700 and £13,900.

Effective long-term solutions for rehabilitating and resettling short-term prisoners have not yet been implemented

3.9 CJI reports since 2011 have indicated that personal development or resettlement and release planning for local short-term prisoners has been inconsistent or too reactive in nature. Recognising the need for additional support, in June 2016, NIPS introduced the Positive Outcomes for Short-Term Prisoners (POST) project in conjunction with NIACRO (an organisation which supports offenders). POST aimed to encourage participation in purposeful activity and offered support across housing, literacy, employability and skills, alongside sign-posting to key services, with CJI commenting that such a programme was “long-overdue”. Prior to POST, the Prisoner Development Model for rehabilitating custodial offenders did not extend to short-term prisoners.

3.10 However, a 2019 independent evaluation of POST found that service provision was lacking in many aspects: the service was not being offered to all short-term prisoners; required assessments and reviews were not all being held; the lead time to complete baseline assessments was too long; and there was overlap with usual NIPS processes. In addition, limitations in the data available meant that the evaluation could not conclude on whether POST was effective in achieving its aims but noted that it did not appear that it was encouraging desistance. NIACRO told us it has some concerns around the evaluation’s Terms of Reference and methodology and, for this reason, it did not fully concur with the findings.

3.11 CJI recommended in 2018 that NIPS reviews its approach and appropriately targets resources towards short-term, high risk individuals to try and reduce reoffending, also highlighting a need for tailored interventions, streamlined referral and assessment processes and prioritisation of prolific offenders. The Prisons 2020 strategy, published in June 2018, also included an objective to ‘Enhance rehabilitation and resettlement opportunities for people in our prison community through improved Through the Gate provision and developing new approaches to dealing with short-term, high risk prisoners.’

3.12 Although CJI stated that NIPS should deliver actions within one year of its report, work is still ongoing to address service provision gaps, and no definitive action plan was developed to address the specific weaknesses identified by the POST evaluation. NIPS is currently working with PBNI to review their joint service provision for the 2023-24 year, however, whilst intentions were that this review would seek to enhance support for short-term prisoners, this now represents an even greater challenge given the increasing prisoner population, and associated PBNI caseloads, alongside continued COVID-19 recovery.

3.13 To deal with short-term prisoners effectively, stakeholders highlighted the need to make connections between the person and support in the community. This is acutely important considering DoJ statistics which highlight that this group are most likely to reoffend (paragraph 3.7), with approximately half doing so within three months of release (paragraph 1.19), making this the critical period for desistance. Release planning and post-custody support are therefore critical, but are not always adequate, for short-term prisoners.

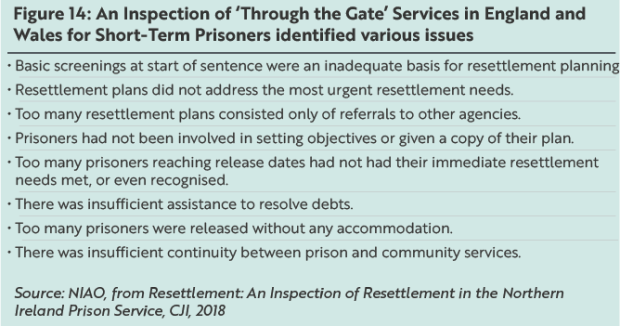

3.14 A 2016 inspection of resettlement services in England and Wales for short-term prisoners found that their needs were not properly identified and planned for (Figure 14). CJI’s 2018 report confirmed that many of these areas were equally relevant to NI. ‘Exit passports’, which include identification information, GP registration and sustainable accommodation on release, were introduced in 2021-22 following significant delay, having been included in the 2015 Desistance Strategy (paragraphs 2.2 to 2.5). This is a positive development, which has the potential to improve resettlement outcomes for this group in particular, but its impact is not yet clear. The Department told us that the effectiveness of this process has been impacted by the pandemic and subsequent resource pressures.

3.15 Longer-term prisoners, by comparison, receive more comprehensive preparation for release, including a detailed release plan and liaison with their prison-based co-ordinator and community-based probation officer to discuss transition. Some must also undertake offending behaviour programmes or pre-release testing where required by Parole Commissioners. Most significantly, longer-term prisoners are subject to periods of statutory supervision on licence by probation officers upon release. However, PBNI has no similar remit for short-term prisoners, despite evidence that they pose the highest reoffending risk. PBNI told us that, currently, probation supervision is tailored specifically to the needs of individuals who pose the highest risk of harm, and that any policy decision to extend its remit would require legislation and significant resources.

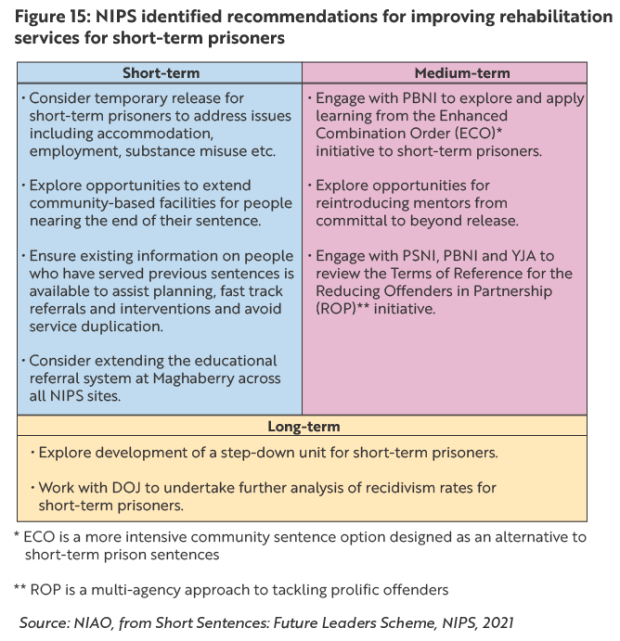

3.16 A 2021 NIPS review identified further recommendations to improve rehabilitation outcomes for short-term prisoners (Figure 15), including improving support for community transition. NIPS has appointed two prison governors to take these forward however, at present, systemic and unresolved gaps remain in respect of responsibilities across government to ensure effective transitional and post-custody support.

3.17 Continuing support to released offenders through to the community setting (‘through the gate’ support) significantly assists resettlement and reduces reoffending risks. Without any structured community-based support mechanism for short-term prisoners, these individuals, whom research shows often encounter significant problems resettling, have no designated contact point to help them access appropriate services post-release. While the VCS can provide some floating support services, inadequate offender awareness of these, or inability to access them without a statutory referral, limits their impact.

Other jurisdictions have sought to strengthen ‘through the gate’ and post-custody support

3.18 Other jurisdictions are further advanced in developing ‘through the gate’ and post-custody support for short-term prisoners. In 2015, England and Wales extended post-custody licence supervision and rehabilitation support to try and reduce reoffending levels, meaning all released prisoners now receive at least 12 months statutory community supervision. A new resettlement model was then introduced in 2021, which included plans for better continuity of support beyond prison and new specialised short-sentence teams to directly address resettlement needs from point of sentencing to community reintegration. The National Audit Office reported on resettlement services for adult prison leavers in England and Wales in May 2023, concluding that, despite these initiatives, challenges remain in relation to release planning and rehabilitation services for prisoners when they leave custody.

3.19 Scotland also implemented the ‘Throughcare’ scheme across most prisons in 2015, offering a mentoring approach for short-term prisoners, instead of formal post-custody supervision, to enable smooth community transition. This involves support officers working with offenders in prison and following release, to change behaviours and provide practical help with issues including housing, medical provision and benefits. A 2017 independent evaluation found that whilst it was too early to definitively conclude on reoffending rates, Throughcare was impacting positively on service users and the wider prison environment.

3.20 Currently, NI clearly lags behind the rest of the UK in seeking to support community resettlement amongst short-term prisoners. In our view, the major gaps in local support can only be contributing to the inadequate progress in addressing these frequent reoffenders. The criminal justice ‘revolving door’ has clear cost-effectiveness implications. Any investment in these individuals whilst in custody is lost when unresolved or re-emerging issues trigger reoffending, and they return to prison to restart the whole cycle.

Recommendation 3

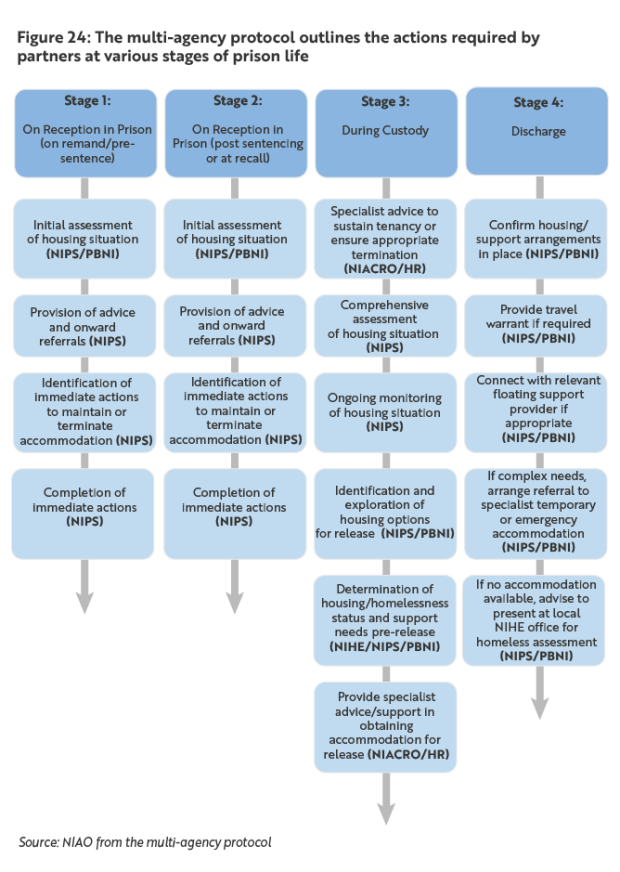

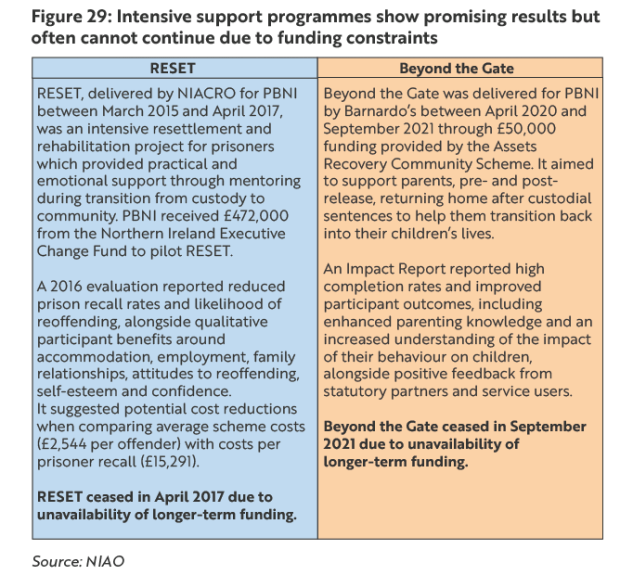

The Department should develop greater and more timely accessibility to rehabilitation initiatives to address the identified gaps in support for short-term prisoners. It should also review the adequacy of ‘through the gate’ support and, along with all relevant stakeholders, devise a solution(s) to better assist short-term prisoners’ transition to the community and resettlement in the early period post-release.