Foreword

In November 2014, the four public audit agencies of the UK, including the Northern Ireland Audit Office, published a good practice guide for public sector workers and employers on whistleblowing, or raising concerns. In the six years since then, a number of developments have highlighted the need for an updated guide. These include legislative change and the publication of significant reports on how to instil an organisational culture which encourages the raising of concerns, in particular the Francis report relating to the NHS.

Our 2014 Guide has been used to inform reviews of arrangements for raising concerns in both the health and social care and the central government sectors in Northern Ireland. The outcomes from these reviews are also reflected in this updated Guide.

In his report on the NHS, Sir Robert Francis said: “There is a need for a culture in which concerns raised by staff are taken seriously, investigated and addressed by appropriate corrective measures. Above all, behaviour by anyone which is designed to bully staff into silence, or to subject them to retribution for speaking up, must not be tolerated.”

I concur with this view and believe it should be applied across all organisations in the Northern Ireland public sector. Staff are a key resource and are often referred to as the “eyes and ears” of an organisation. As such, they should be properly valued and listened to if they come forward, in the wider public interest, to raise issues of concern. Raising concerns and being listened to should be part of the normal business of any healthy organisation.

In addition, the public inquiry into the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) in Northern Ireland explored the role of a person who was not a public sector employee but who raised concerns which, had they been properly considered, would have led to a more effective response to the weaknesses of the RHI scheme. I have therefore emphasised in this updated guide the importance of public sector organisations having effective arrangements for receiving concerns from the wider public and ensuring that they are properly considered and appropriately acted upon. I have advocated a raising concerns champion in each organisation who can be a source of advice and support for staff but, in addition, a key resource for connecting the organisation to service users and the wider public.

I have also provided separate guidance for members of the public (see Appendix 1) to signpost more clearly how they can make themselves heard if they wish to raise a concern in the public interest.

I believe the Senior Leadership Team in every public body in Northern Ireland should review formally the effectiveness of their arrangements for raising and responding to concerns from all sources against the good practice principles set out in this guide. It is important that such reviews are more than tick-box exercises. They must tackle head-on the real and perceived cultural barriers to raising concerns, should be overseen by the Board and include a clear action plan to address any deficiencies. Strong and visible leadership is key to promoting the necessary culture change.

Appendix 5 of this Guide provides a checklist for organisations, designed to support them in assessing and enhancing their current culture and practices around raising concerns.

Kieran Donnelly CB

Comptroller and Auditor General

25 June 2020

Key Messages

ORGANISATIONAL CULTURE “Organisations must: take steps to instil a culture in which workers have the confidence to raise concerns openly; listen to all concerns raised; and protect those who speak up.”

RAISING CONCERNS AS PART OF NORMAL BUSINESS

“Organisations should strive to establish a culture in which raising concerns is regarded as natural and routine.”

RAISING CONCERNS CHAMPION

“A raising concerns champion can be a source of advice and support for staff but, in addition, a key resource for connecting the organisation to service users and the wider public.”

STRONG, VISIBLE LEADERSHIP

“If senior managers and board members have a presence across an organisation and speak with staff informally on a regular basis, they are better placed to influence the culture, encourage openness and get a better understanding of the issues which are important to staff.”

Section 1: Introduction

Origins and Purpose

The origins

Best practice guidance and the legislation to protect workers raising concerns was developed following a number of disasters and public scandals in the late 1980s and early 1990s such as:

- the capsizing of the passenger ferry the Herald of Free Enterprise outside the port of Zeebrugge, 1987;

- the explosion on the Piper Alpha oil platform, 1988;

- the train collision at Clapham, London, 1988; and

- the Bristol Royal Infirmary scandal, late 1980s to early 1990s.

In each of these cases, workers had known of the dangers but did not know what to do or who to approach, were too frightened to speak out for fear of losing their jobs or being victimised, or spoke out but were not listened to.

A workplace culture which encouraged the raising of concerns and where workers felt confident that they could safely raise concerns without reprisal or discrimination could have prevented these disasters and scandals or greatly reduced their impact.

Purpose of this Guide

This updated Guide (see Foreword) is aimed at helping employees and public sector organisations to understand the value of an open and honest reporting culture, where concerns can be raised and dealt with effectively as part of normal business, leading to strengthened governance.

While aimed primarily at public sector organisations and their employees, the Guide also explains how the general public can raise concerns (see page 15) and how these should be treated by organisations (see page 29).

Although not covered by public interest disclosure legislation, concerns raised by the general public can play a vital role in identifying wrongdoing, risk or malpractice within the Northern Ireland public sector. This was highlighted in the recent inquiry into the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme.

A separate information leaflet for members of the public has been produced and is included in this Guide at Appendix 1.

Raising a concern or whistleblowing?

Raising a concern in the public interest is the action of telling someone in authority, either internally and/or externally (e.g. regulators or media), about wrongdoing, risk or malpractice.

There can be confusion around the terms ‘raising a concern’ and ‘whistleblowing’. Some wrongly believe that they are separate steps involving an ‘escalation’, i.e. someone ‘raises a concern’ then, if they feel they have not been heard, they ‘blow the whistle’ within their organisation or to an outside body. This is a misunderstanding. Whistleblowing and raising a concern are the same thing.

The term ‘whistleblowing’

The term ‘whistleblowing’ does not exist in law. It is a word that has become commonly associated with the action of raising a concern, usually by an employee or worker, about what they believe is wrongdoing within their organisation.

Sir Robert Francis QC completed a review of the reporting culture in the NHS following the Mid Staffordshire Hospital Trust case (see page 18). He believed the term ‘whistleblowing’ contributed to some of the barriers that prevent concerns being raised:

“..there is confusion about what qualifies as whistleblowing. Some people consider whistleblowing to be about something concerned with criminal wrongdoing such as fraud, rather than a patient safety concern. Some consider it applies when escalating a concern outside the normal management chain, or about a more senior colleague. Some believe it only applies when raising a concern outside the organisation, or even that it is limited to disclosure to the media or otherwise into the public domain;

“..the term has negative connotations, or can imply something separate from, and more serious than, raising a concern as a normal activity.”

Sir Robert went on to say:

“I gave serious consideration to recommending that the term ‘whistleblower’ should be dropped, and some other term used instead. Although I still have reservations about the term, I have been persuaded that it is now so widely used, and in so many different contexts, that this would probably not succeed. Instead we should focus on giving it a more positive image.”

Sir Robert’s vision was that raising concerns should be “part of the normal routine business of any well-run NHS organisation”.

This same vision can be applied across the wider public sector. The ideal is that whistleblowing, or raising concerns, is not viewed with fear and negativity but as a normal, positive part of everyday business (see page 35).

Concerns raised provide public bodies with an important source of information that may highlight serious risks, potential fraud or corruption. Workers are often best placed to identify deficiencies and problems before any damage is done, so the importance of their role as the ‘eyes and ears’ of organisations cannot be overstated.

Concern, grievance or complaint?

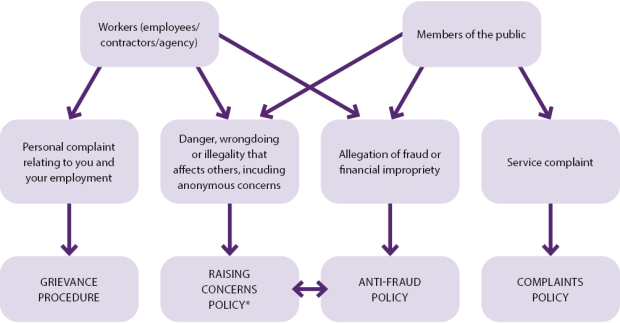

The nature of the issue being raised will determine whether it is a concern (whistleblowing), a grievance or a complaint, and therefore the appropriate policy under which it should be addressed.

Concern:

Whistleblowing may be called speaking up or raising a concern. It is all about ensuring that if someone sees something wrong in the workplace, they are able to raise this within the organisation, or to a regulator, or more widely. Whistleblowing ultimately protects customers, staff, beneficiaries and the organisation itself by identifying harm before it’s too late.

Protect (formerly Public Concern at Work)

When someone blows the whistle they are raising a concern about danger, illegality or wrongdoing that affects others. The person raising the concern is usually not directly or personally affected, they are simply trying to alert others who can address the issue. For this reason, they should not be expected to prove the malpractice. Such concerns should be handled in line with an organisation’s raising concerns/whistleblowing policy.

A concern may be raised by someone internal to the organisation, generally a member of staff, or by someone external to the organisation (see Figure 1 on page 14). For more information on the types of concerns which you can raise, see page 21.

Grievance:

Grievances are concerns, problems or complaints raised by a staff member with management. Anybody may at some time have problems with their working conditions or relationships with colleagues that they may wish to raise.

Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (Acas)

When a worker in an organisation raises a grievance, they are saying that they personally have been treated poorly. This may involve, for example, a breach of their individual employment rights or bullying, and the person is seeking redress or justice for themselves. They therefore have a vested interest in the outcome and, for this reason, are expected to prove their case. Such issues should be handled in line with an organisation’s grievance policy.

Complaint:

A complaint is when a customer brings a problem to the attention of the organisation and expects some redress, probably over and above simply supplying the original product or service that was the cause of the complaint.

The Institute of Customer Service

A customer or service user may complain about a product supplied or a service provided to them. They will have been personally affected by a faulty product or poor service and will be seeking some form of compensation or redress. Such issues should be handled in line with an organisation’s complaints policy.

Figure 1 summarises the types of issues that may be raised and the relevant policies which should apply:

*Organisations should have a raising concerns policy which can deal with issues raised both by workers and members of the public. Alternatively, they may choose to have a separate policy for dealing with concerns raised by the wider public. (See pages 15 and 29 and Appendix 1 of this Guide which discuss concerns from members of the public.)

What if it’s not clear cut?

There can be instances where a person raises an issue which has elements both of a wider concern affecting others and of personal interest. The challenge for organisations is to disentangle the issues and deal with each in accordance with the relevant policy.

Can a member of the public raise a concern?

A member of the public can raise concerns directly with any public sector organisation. As Figure 1 shows, the nature of the issue raised will determine the policy under which the organisation should consider the matter.

Many organisations regard “whistleblowing” as an internal matter, involving only staff of the organisation. But, for example, a visitor to a hospital may witness a potential danger, or a member of the public may know about potentially fraudulent behaviour by a public official. These people are not directly affected by the matter but wish to raise a concern in the public interest. Such concerns must be treated seriously and should be dealt with in the same way as concerns raised by staff members. It is the issue being raised which is important, not the person raising it.

Instead of an internal line of reporting (as provided to staff wishing to raise a concern), organisations should provide a single point of contact for members of the public wishing to raise a concern in the public interest, who will receive their concerns and ensure that they are dealt with appropriately (see page 29).

“I’m looking back over some of the real heavy reports we took to the Public Accounts Committee over the past five years — a lot of the high-graded intelligence actually came from whistleblowers in the wider community”

Source: Comptroller and Auditor General, RHI Inquiry, 19th October 2018

What types of concerns can a member of the public raise?

A member of the public can raise the same types of concerns as an employee or worker (see page 21).

Legal remedy

Workers have a retrospective remedy in employment law, in that they can take a case against their employer at an employment tribunal if they are victimised or suffer detriment as a result of raising a concern (see Appendix 2). This legal remedy is not available to a member of the public raising a concern, as there is no employment relationship with the public sector organisation.

Alternative points of contact

“I don’t think anybody in the public really knows what the correct procedures are for bringing grievances to the Department and, if they’re not being heard, what to do then….. I didn’t know what the protocol was then, and I still effectively don’t now, about how to move that forward if I felt I wasn’t being heard.”

Source: RHI whistleblower, RHI Inquiry, 9th February 2018

A member of the public has the option of raising their concern with an independent body, such as the Northern Ireland Audit Office. An information leaflet for the public has been published in association with this Guide (and is reproduced at Appendix 1), providing further information. Public sector organisations should ensure that this leaflet is available on their websites, and more widely as appropriate.

Additional assurances for workers

Whilst organisations should apply the same process when considering concerns raised by both internal and external sources, an organisation will have additional responsibilities in relation to a worker, because of the employment relationship. In particular, these will include ensuring that the worker has appropriate advice and support and does not suffer detriment as a result of raising a concern. More detail is provided at page 25.

Section 2: Workers

Why should I raise a concern?

“The leadership of an organisation cannot act if it is not told about things that are going wrong, inappropriate behaviour or even honest fears that something does not feel right.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

The decision to raise a concern can be a difficult one. However, workers (see Appendix 3) are the eyes and ears of an organisation and responsible employers should want to address concerns such as health and safety risks, potential environmental problems, fraud, corruption, the misuse of public funds, deficiencies in the care of vulnerable people, cover-ups and other such issues. Addressing problems before damage is done should be the ultimate goal for both workers and employers.

Raising concerns is essential to:

- safeguard the integrity of an organisation;

- safeguard employees;

- safeguard the wider public; and

- prevent damage.

“Raising concerns can save lives, jobs, money and the reputation of professionals and organisations. It is an early alert system.”

Source: Draw the line: A managers’guide to raising concerns, NHS Employers, March 2017

Case example – Mid Staffordshire Hospital Trust

Helene Donnelly, a nurse in Stafford Hospital Accident and Emergency Department, raised concerns after she "saw people dying in very, very undignified situations which could have been avoided". Nurses were not trained properly to use vital equipment, while inexperienced doctors were put in charge of critically ill patients. The public inquiry into the failings revealed one of the biggest scandals in the history of the National Health Service (NHS). The inquiry report made 290 recommendations for improvements in care across the NHS.

In 2014, Helene Donnelly received an OBE for services to the NHS. She became an ambassador for cultural change at the Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Partnership NHS Trust, taking staff concerns directly to the Chief Executive. She said “I hope this [honour] is recognition for lots of other people trying to raise concerns and this is also for the positive change we’re trying to encourage now.”

How should I raise a concern?

“Suggesting that workers consider raising a concern with their manager, and at the same time offering alternatives to line management, are both essential for any policy to be effective.”

Source: Review of the Operation of Health and Social Care Whistleblowing Arrangements,Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RQIA), September 2016

Follow your organisation’s policy

Your employer should have a policy in place for raising concerns (see Appendix 4). This is accepted good practice, although not required by legislation. The policy should set out how you can raise concerns either internally or externally. You should be aware that:

- you do not need firm evidence before raising a concern, only a reasonable suspicion that something may be wrong;

- you are a witness to potential wrongdoing and are merely relaying that information to your employer; and

- it is the responsibility of your employer to use the information you provide to investigate the issue raised.

Raising a concern internally

Step 1

If you have a concern, raise it first with your line manager or team leader, either verbally or in writing.

Step 2

If you feel unable to raise the matter with your manager, for whatever reason, raise the matter with a designated officer (alternative contact names should be provided in your organisation’s policy for raising concerns).

If you want to raise the matter in confidence, you should say so at the outset so that appropriate arrangements can be made.

Step 3

If after Step 1 or Step 2 you feel your concern has not been addressed satisfactorily, or if you feel that the matter is so serious that you cannot discuss it with any of the above, you should contact the head of your organisation and/or a Board Member (e.g. Non-Executive Director, Chair, Audit Committee).

Raising a concern externally

If you feel unable to raise a concern internally, or have done so but feel the matter has not been adequately addressed, your organisation’s policy should provide information on appropriate external points of contact.

In Northern Ireland there is a range of possible external contacts, depending on the nature of the concern you wish to raise. For example:

- If your concern is about health and safety at work, the appropriate contact will be the Health and Safety Executive for Northern Ireland.

- If your concern is about possible fraud or corruption in central government or health service organisations, the appropriate contact will be the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland.

Your organisation’s policy may provide details of the most appropriate external contacts for your area of work. A full list of external bodies with whom you can raise concerns (known as “prescribed persons”), and their remits, is set out in legislation (see footnote 8).

“Staff should never be made to feel hesitant about raising an issue with a relevant authority outside the organisation.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

What if my employer doesn’t have a policy in place?

All Northern Ireland public sector organisations should have a policy in place for raising concerns. However, if your employer does not have a policy, you should still report your concerns to your line manager or an appropriate senior manager within your organisation. You also have the option of raising your concern with the relevant external contact (see footnote 8).

Am I protected if I raise a concern?

The key protection you should expect and have is the good practice of your employer (see page 26).

Public Interest Disclosure legislation allows an employee to take their employer to an employment tribunal if they suffer detriment in any way as a result of raising a concern (referred to in the legislation as making a disclosure in the public interest – see Appendix 2).

What types of concern can I raise?

You can raise concerns about any issue relating to suspected malpractice, risk, abuse or wrongdoing that is in the public interest. You will not need to have evidence or proof of wrongdoing. As long as you have an honest belief, it does not matter if you are mistaken. It is best to raise the concern as early as possible, even if it is only a suspicion, to allow the matter to be looked into promptly.

The types of issues about which you can raise concerns include:

- any unlawful act (e.g. theft or fraud);

- health and safety risks to employees, service users or the public;

- the abuse of children or vulnerable adults in care;

- damage to the environment (e.g. pollution);

- failing to safeguard personal and/or sensitive information (data protection);

- abuse of position; or

- any deliberate concealment of information tending to show any of the above.

The type of concern you wish to raise will determine which external body you should contact, should you wish to go outside your own organisation (see footnote 8).

Further information on the types of concerns that can be raised is available at:

https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/blowing-whistle-workplace-wrongdoing

Case examples:

A care assistant in an old people’s home was worried that one of the managers might be stealing cash from residents by recording pocket money paid out to residents but keeping it for himself. The care assistant raised his concerns with the owners of the home. An investigation quickly found that the care assistant was right and the manager was dismissed.

Source: Protect (formerly PCaW)

A newly qualified allied health professional (AHP) raised concerns with his supervisor about a senior colleague’s behaviour. He was asked to put the concerns in writing. The Trust believed there to be merit in the claims and referred the senior professional to their professional regulator.

The AHP gave evidence at the resulting Fitness to Practise hearing and felt supported throughout. The senior clinician left the trust and it transpired that many other staff had also had concerns about that clinician.

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

An NHS training co-ordinator was concerned that his boss was hiring a friend to deliver training on suspicious terms which were costing the Trust over £20,000 a year. More courses were booked than were needed and the friend was still paid when a course was cancelled. The co-ordinator saw the friend enter the boss’ office and leave an envelope. His suspicions aroused, he looked inside and saw that it contained a number of £20 notes.

The co-ordinator raised his concerns with a director at the Trust who called in NHS Counter Fraud. The suspicions were right: his boss and the trainer pleaded guilty to stealing £9,000 from the NHS and each received 12 month jail terms, suspended for two years.

Source: Protect (formerly PCaW)

Must I raise a concern openly?

“Managers and team leaders should encourage and support a culture where staff can raise concerns openly and without fear of reprisal.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

You can raise a concern:

- openly – you have no concerns about revealing your identity;

- confidentially – you provide your personal details to your point of contact but do not wish them to be shared widely beyond that; or

- anonymously – you do not reveal your identity when raising your concern.

Openly

Raising a concern openly means you are happy to be identified as the person who raised the concern. Openness makes it easier for your employer to investigate and obtain more information about your concerns. Openness can also encourage others to come forward, as they will know that a concern has been raised. The culture of your workplace (see page 36) may influence whether or not you are comfortable raising a concern openly.

Confidentially

Raising a concern in confidence means you are content to provide your name and contact details but want your identity protected as far as possible. Your employer’s arrangements should provide assurance that this will be the case. However, it may not always be possible to maintain confidentiality if this impedes the investigation. In such circumstances, it is vital that you are consulted and, if possible, your informed consent obtained.

Your organisation’s policy for raising concerns should include:

- procedures for maintaining your confidentiality to the maximum extent possible;

- procedures for consulting with you and, where possible, gaining your consent prior to any action that could identify you; and

- strategies for supporting you and ensuring you suffer no detriment or harassment when confidentiality is not possible or cannot be maintained.

Even if your organisation’s policy for raising concerns does not include assurances about protecting your identity, your employer’s duty of care towards you should ensure that they respect your confidentiality if you request it.

If your confidentiality is not protected, and you suffer detriment as a result, you may be able to seek recourse through an employment tribunal, as the following case example demonstrates:

Case example – Lingard v HM Prison Service

Lingard, a female prison officer, raised concerns with senior managers that a fellow officer had arranged for a bogus assault charge to be filed against a prisoner and had asked other colleagues to plant pornography in the cell of a convicted paedophile.

Without telling her, Lingard’s managers identified her as the source of the concerns. As a result, she was ostracised. She received no support from the Prison Service even though she was clearly suffering stress. A senior manager argued that Lingard’s whistleblowing showed she was disloyal and she was eventually forced out.

Lingard took her case to an Employment Tribunal, citing detriment caused by her identity being revealed. Lingard won her case and received a substantial financial award. The Director General of the Prison Service said the case was indefensible and that lessons needed to be learned.

Source: PCaW, Where’s Whistleblowing Now? 10 years of legal protection for whistleblowers

Anonymously

Raising a concern anonymously means you choose not to reveal any of your personal details, such as name and contact number. Your employer should still accept anonymous concerns and commit to giving them due consideration, however, there are disadvantages to raising concerns anonymously:

- Detailed investigations may be more difficult, or even impossible, to progress if you choose to remain anonymous and cannot be contacted for further information.

- The information and documentation you provide may not easily be understood and may need clarification or further explanation.

- There is a chance that the documents you provide might reveal your identity.

- It may not be possible to remain anonymous throughout an in-depth investigation.

- It may be difficult to demonstrate to a tribunal that any detriment you suffer is as a result of raising a concern.

“Policies ……should explicitly permit concerns to be raised anonymously.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

What should I expect from my employer if I raise a concern?

“Employers should show that they value staff who raise concerns, and celebrate.…the improvements made in response to issues identified.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

You can raise a concern informally with your line manager (see page 19) and may feel more comfortable doing so. However, some concerns, by their nature and scale, will require a more formal process of review and investigation than others. When you raise a concern, you should expect that your employer will:

- formally acknowledge receipt of your concern;

- offer you the opportunity of a meeting to fully discuss the issue, so long as you have not submitted your concern in writing anonymously;

- if an investigation is appropriate, formally notify you who will be investigating your concern;

- respect your confidentiality where this has been requested. Confidentiality should not be breached unless required by law;

- take steps to ensure that you have appropriate support and advice;

- agree a timetable for feedback. If this cannot be adhered to, your employer should let you know;

- provide you with appropriate feedback; and

- take appropriate and timely action against anyone who victimises you as a result of raising a concern.

Overcoming possible barriers to raising concerns

There may be reasons why you would be reluctant to raise concerns, in particular:

- you don’t trust internal arrangements;

- you feel uncomfortable with a formal process;

- you don’t believe anything will be done; or

- you believe you will suffer as a result of raising a concern.

Good practice by your employer should remove any barriers to raising concerns. Good practice is key to ensuring that concerns are properly dealt with and that detriment doesn’t occur.

You should expect your employer to have the following essential elements of good practice in place:

- an open and honest culture;

- a clear policy and procedures;

- concerns taken seriously and given due consideration;

- assurance on confidentiality; and

- a zero tolerance of any reprisals or detriment.

Reasonable expectations

While you should expect your employer to treat your concerns seriously and give them due consideration, not all cases will require a full investigation. For example, there may be other circumstances, of which you are not aware, which put a different perspective on your concerns. Your employer should explain the possible courses of action that may be taken and, ideally, should notify you about the proposed course of action.

When you raise a concern, you may not always get the outcome you want or expect. However, you should always expect that you will be taken seriously and that the matter will be handled fairly and properly, in accordance with documented procedures.

Section 3: Public Sector Organisations

Why is it important to know about concerns?

As a responsible public sector organisation, you should want to know about malpractice, risk, abuse or wrongdoing in your organisation. Workers who are prepared to speak up about such issues should be recognised as one of the most important sources of information for any organisation seeking to enhance its reputation by identifying and addressing problems that disadvantage or endanger other people.

You should have in place a policy which demonstrates commitment from the top of the organisation that concerns are welcomed and will be treated seriously (see Appendix 4), and your organisation should take steps to develop and maintain a culture in which workers are encouraged to raise concerns (see page 36). Your organisation should also be alive to the value of concerns raised by members of the public (see page 29).

The benefits to your organisation of encouraging the raising of concerns include:

- identifying wrongdoing as early as possible;

- exposing weak or flawed processes and procedures which make the organisation vulnerable to loss, criticism or legal action;

- ensuring critical information gets to the right people who can deal with the concerns;

- avoiding financial loss and inefficiency;

- maintaining a positive corporate reputation;

- reducing risks to the environment or the health or safety of employees or the wider community;

- improving accountability; and

- deterring workers from engaging in improper conduct.

The potential risks in discouraging the raising of concerns include:

- missing an opportunity to deal with a problem before it escalates;

- compromising your organisation’s ability to deal with the allegation appropriately;

- serious legal implications if a concern is not managed appropriately;

- significant financial or other loss;

- the reputation and standing of your organisation suffering;

- a decline in public confidence in your organisation and the wider public sector; and

- referral by a worker to an external regulator or prescribed person (see page 20), potentially bringing adverse publicity to your organisation.

How should we treat concerns from members of the public?

Figure 1 on page 14 shows that concerns about danger, wrongdoing or illegality affecting others may be received both from workers within an organisation and from members of the public.

Public sector organisations should have a raising concerns policy and procedures which can deal with issues raised from both sources, or they may choose to have a separate raising concerns policy for issues raised by the wider public. Either way, the process for considering the concerns raised, and dealing with them appropriately, should be largely the same.

While workers will have an internal line of reporting, with their line manager as the first point of contact, public sector organisations should provide an obvious and well sign-posted route for members of the public wishing to raise a concern in the public interest. This may take the form of, for example, a speak-up guardian or raising concerns champion who can be a source of advice and support for staff but, in addition, a key resource for connecting the organisation to service users and the wider public.

The role of a raising concerns champion may be part-time or full-time, depending on the size of an organisation and the nature of its business.

It is essential that the raising concerns champion has good communication skills and an understanding of the importance to the organisation of receiving concerns from all sources, including external sources, and ensuring they are dealt with effectively. In addition, the raising concerns champion should:

- understand the types of public interest concerns their organisation can consider and, if necessary, re-direct the member of the public to a more suitable organisation;

- log the concern;

- ensure the concern is directed to the most appropriate person in the organisation for proper consideration and appropriate action;

- liaise periodically with those in the organisation handling concerns, to ensure progress is made and appropriate feedback is provided to the member of the public; and

- have the authority, where necessary, to escalate concerns to the top of the organisation.

“What do people do whenever they go to a department — any department — with a concern and they feel that they’re not being listened to? Where do they go next? I don’t know where that is and I still don’t know.”

Source: RHI whistleblower, RHI Inquiry, 9th February 2018

“I think this probably is one of the themes that… the panel will be considering in pursuance of their terms of reference, because they are asked to look generally at how whistleblowers, or concerned citizens, are and should be treated by the various arms of government with whom they may interact.”

Source: Mr Scoffield QC, RHI Inquiry, 9th February 2018

The Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) Inquiry discussed the role of citizens who bring concerns to a public sector organisation and how they are, or should be, treated. The Inquiry report, published in March 2020, commented on arrangements in the relevant government department:

“No guidance existed on handling concerns raised by a concerned member of the public until June 2016….. there does not appear to have been any recognised system for managing and collating correspondence of the type received from Ms O’Hagan in 2014 and 2015. The Inquiry has no doubt that this sorry sequence of events fell well below what a citizen of this jurisdiction, concerned about potential waste of public funds, was entitled to expect.”

In relation to concerns from members of the public, the Inquiry recommended:

“Better systems are needed for spotting early warnings and concerns from the public and businesses that something unexpected could be happening or going wrong….. Simply updating existing complaints and whistleblowing policies, although helpful, will not be sufficient, since relevant intelligence often does not come through these routes. The default response amongst officials should be one of curiosity rather than assuming the concern is misplaced. We recommend that all Northern Ireland departments review their processes for obtaining, handling and responding to information from multiple routes, to ensure that they have robust systems to pick up early warnings and repeated signals, as well as evidence that a policy is working as intended.”

The raising concerns champion recommended on page 29 of this Guide is one way of ensuring that all correspondence is processed properly and effectively.

What a member of the public should expect when they raise a concern

Page 25 of this Guide sets out what a worker should expect from their employer when they raise a concern. Similarly, a member of the public who raises a concern with a public sector organisation should expect the following:

- a formal acknowledgement of receipt of their concern;

- an opportunity to meet with the organisation to fully discuss the issue and provide evidence, if desired;

- an indication of how the matter might be progressed;

- respect for their confidentiality where requested;

- an indication of when they might expect feedback, if they wish to receive feedback; and

- provision of appropriate feedback.

Public sector organisations should ensure that members of the public who raise concerns are made aware of alternative points of contact. The separate public information leaflet published along with this guide (and included at Appendix 1) should be made available on organisations’ websites. Hard copies should also be made available where appropriate, for example in the reception area of organisations’ premises.

How do we know concerns are being raised for genuine reasons?

“Suggestions of ulterior purposes have for too long been used as an excuse for avoiding a rigorous examination of safety and other public interest concerns raised by….staff.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

Organisations can often focus on who is raising the issue and what their motivation might be, rather than focusing on the information being provided. The issue or concern being raised should always be the key piece of information.

Sir Robert Francis QC (see footnote 7) recognised this problem:

“Too often, people resort to formal process and make assumptions that the person who identifies a problem is the problem. Hard pressed managers are often given insufficient resources to ensure that the facts are established objectively and swiftly each time a concern is raised, and instead hunt for someone to blame……..a culture of blame leads to entrenched positions, breakdown of professional relationships and considerable suffering, utterly disproportionate to the nature of the problem from which this process originated.

“We need to get away from the culture of blame, and the fear that it generates, to one which celebrates openness and commitment to safety and improvement.”

The majority of people raising concerns will have no ulterior motives; they simply want to highlight an issue that needs to be addressed for the good of their organisation and the wider public interest. But even if a person does have an ulterior motive, such as deflecting from weaknesses in their own performance, there may still be validity in the issues they raise. Any staff performance or grievance issues should be dealt with separately under relevant HR procedures, but the concerns raised should not be ignored.

Good faith v Public interest

The law which offers a retrospective remedy to workers raising concerns, should they suffer as a result of doing so, has recognised that acting in good faith is not a pre-requisite for raising a concern. Since 1st October 2017 in Northern Ireland, the pre-existing good faith test has been replaced with a public interest test. So if a worker raises a concern in the public interest, regardless of their motivation, they will have the protection of the legislation should it be required. The issue of good faith will only be taken into account by a tribunal when considering the level of remedy awarded.

False allegations

Deliberately raising a false allegation is always unacceptable and sets back the cause of an open and honest culture by introducing mistrust. Organisations should take disciplinary action against any member of staff making a false allegation.

Sir Robert Francis highlighted the issue of false allegations:

“The best way to meet the possibility of false allegations, dishonestly made, is to investigate and establish that they are false, and by separating this from any existing process in relation to the individual.”

How do we make raising concerns a part of normal business?

“We need to get to the point where it is not considered exceptional, inappropriate, a matter of criticism or a matter for blame to raise concerns.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

Staff may feel content to mention a concern to their line manager but they fear “whistleblowing”, seeing it as something more formal and serious, with potential repercussions. Page 11 of this Guide highlights the confusion around the terms “raising concerns” and “whistleblowing”. In reality they are the same thing.

Some concerns, by their nature and scale, will require a more formal process of review and investigation than others, but the fundamental purpose in every case is the same - to bring into the open an issue of concern so that it can be properly addressed by those in authority, thereby avoiding or minimising harm, risk, wrongdoing or malpractice, and protecting the reputation of the organisation. Remember, it is the issue being raised which is the key thing, not the person raising it.

Organisations should strive to establish a culture in which raising concerns is regarded as natural and routine. An open, honest culture, which seeks to learn and not apportion blame, is essential (see page 36).

“Having open and honest conversations about issues that concern staff as part of your team meetings, staff briefings and one to ones will help normalise the process. It will also help to reinforce that raising concerns is everyone’s responsibility.”

Source: Draw the line: A managers’ guide to raising concerns, NHS Employers, March 2017

Making raising concerns a normal activity

As an organisation, there are practical steps you can take to make raising concerns a part of normal business, for example:

- Have regular manager-led team meetings and encourage informal discussion by asking some simple open questions, for example:

- What has gone well this month for the team?

- What could have gone better?

- Are there any concerns we need to address as a team, to promote improvement?

- Are there any learning points we can share?

- Publicise examples of concerns that have been raised and dealt with effectively. This can be done via staff newsletters or the organisation’s intranet. This will help staff see the positive value of raising concerns.

- Focus on the issue being raised and not on the person raising the issue. If staff see evidence of concerns being listened to and responded to effectively, they will be happier to raise concerns in the course of normal business.

- Have a policy and procedures (see Appendix 4) that encourage all concerns to be raised, no matter how small, giving examples. If staff can become more comfortable raising minor everyday issues, this will help them feel comfortable raising more serious concerns. And always treat low level concerns seriously – the person may be “testing the system” before raising a major issue.

How can we create a culture that encourages raising concerns?

“Positive experiences of whistleblowing were …generally attributed to working in an organisation with a culture of openness … feeling supported during the process, and maintaining good working relationships with colleagues.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

If your organisation is serious about addressing misconduct, risk, abuse and wrongdoing, it must: take steps to instil a culture in which workers have the confidence to raise concerns openly; listen to all concerns raised; and protect those who speak up.

Culture

Your organisation’s policy for raising concerns and your code of conduct should include a clear commitment from senior management to develop and maintain an open and ethical culture. The head of your organisation should strongly endorse the policy. There should be a clear message that no issue or concern is too small.

The following factors will encourage workers to raise concerns:

- supportive organisational culture where raising concerns is welcomed;

- clear and explicit management commitment, from the top of the organisation, to an open and honest culture;

- a strong policy and code of conduct reinforcing the expectation of ethical behaviour from staff at all levels;

- clear roles and responsibilities in relation to dealing with concerns;

- clear procedures and lines of reporting for workers wishing to raise concerns;

- consistent handling of concerns raised, which should all be treated seriously;

- a specialist resource with detailed knowledge of raising concerns, who can provide advice to management and staff and be an alternative to line management for workers wishing to raise a concern;

- effective awareness training for all staff so they know what concerns they can raise and how to raise them;

- effective training for line managers in dealing with concerns raised;

- a clear understanding of the benefits of raising concerns;

- continuing communication of your organisation’s commitment to an open and ethical culture, through circulars, posters, emails and your intranet; and

- regular attitude surveys to determine the level of confidence staff have in arrangements for raising concerns.

Visible leadership

The right kind of leadership, at different levels within an organisation, is essential to creating a culture where people feel comfortable raising concerns. In his report on the culture within the NHS (see footnote 7), Sir Robert Francis highlighted the importance of visible leadership and the difference it can make.

If senior managers and board members have a presence across an organisation and speak with staff informally on a regular basis, they are better placed to influence the culture, encourage openness and get a better understanding of the issues which are important to staff.

A 2016 review of whistleblowing arrangements in the health and social care sector in Northern Ireland highlighted an awareness of the need to create an open and honest culture. Examples of measures already in place in some organisations to promote visible leadership include:

- senior management and board member walkabouts;

- staff open forums where senior staff are available to listen to staff concerns; and

- a learning and development steering group in one organisation, chaired by a non-executive board member, to discuss concerns, using scenarios to promote learning.

“Culture and behaviour in an organisation is influenced by the signals the leadership sends about what it values. Public recognition of the benefits and value of raising concerns sends a clear message that it is safe to speak up and that action will be taken.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

The Freedom to Speak Up report went on to say:

“Visible leadership is essential to the creation of the right culture. Leaders at all levels, but particularly at board level, need to be accessible and to demonstrate, through actions as well as words, the importance and value they attach to hearing from people at all levels.”

Case example

A junior member of staff emailed a CEO about a concern. The CEO immediately responded in a personal email, and went to talk to the staff member. The staff member was initially taken aback, and slightly inhibited, but then opened up and commented that the CEO was ‘really normal’ and easy to talk to. This helped to promote the CEO’s reputation as someone who was approachable and willing to listen.

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

Listening

An open and ethical culture is essential to encouraging employees to raise concerns or speak up. A key part of that culture is ensuring that those in a position to respond to a concern listen.

Protection

An open and honest culture and good practice by employers is the key protection for those wishing to raise concerns in their place of work. While public interest disclosure legislation may provide a legal remedy, it may only be accessed after things have gone wrong internally (see Appendix 2).

“Encouraging employees to speak up counts for little if those who speak up are ignored, suppressed, punished, or see their ideas going precisely nowhere.”

Source: Speak Up: Say What Needs to be Said and Hear What Needs to be Heard, Megan Reitz and John Higgins

As a line manager, what are my responsibilities?

“Managers need to be provided with the competence and confidence to enable them to respond to and address concerns raised with them.”

Source: Review of the Operation of Health and Social Care Whistleblowing Arrangements, RQIA, September 2016

Your organisation’s policy should recommend that concerns are raised internally in the first instance, usually through a line manager. To ensure that this reporting route is effective, your organisation should ensure that all line managers who may receive concerns from staff have been given appropriate training on the content and operation of your organisation’s policy.

As a line manager, it is essential that you fulfil your responsibilities in a way that supports the person raising a concern. This will give the person assurance that they have done the right thing by bringing their concern to you.

Managers who receive concerns from workers should:

- have a positive and supportive attitude towards workers raising a concern;

- record as much detail as possible about the concern being raised and agree this record with the worker;

- be aware of the process following the raising of a concern and explain this to the worker;

- make sure the worker knows what to expect, for example in relation to feedback on their concern;

- assure the worker that their confidentiality will be protected as far as possible, if they request this (see page 40);

- make no promises and manage the expectations of the worker;

- make clear that your organisation will not tolerate harassment of anyone raising a genuine concern and ask the worker to let you know if this happens;

- refer the worker to available sources of support, for example Protect or their union; and

- pass the information as quickly as possible to those within your organisation responsible for dealing with concerns (usually someone within senior management), so that the appropriate procedures for consideration and investigation of the concern can be initiated.

“All managers should receive bespoke training in the operation of their policy for raising concerns.”

Source: Review of the Operation of Health and Social Care Whistleblowing Arrangements, RQIA, September 2016

As an employer, how do we address confidentiality?

“Our research highlighted a wide variation amongst policies….Problems included…mistaken or incomplete descriptions about confidentiality and anonymity.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

The best organisational culture is one in which workers feel comfortable raising concerns openly without fear of reprisal, and where the raising of concerns is welcomed (see page 36). This makes it easier for the organisation to assess and investigate any issues, gather more information and reduce any misunderstandings. Pages 23 and 24 set out the differences between raising a concern openly, confidentially or anonymously.

Confidentiality

While openness is the ideal, in practice some staff will have good reason to feel anxious about identifying themselves at the outset and so your policy for raising concerns should ensure they can also approach someone confidentially. This means that their identity will only be known by the person with whom they raise their concern, and will not be revealed further without their consent, unless this is required by law.

While confidentiality should be assured if requested, you should point out potential risks to the worker:

- Colleagues may try to guess the worker’s identity if they become aware that a concern has been raised.

- As any investigation progresses, there may be a legal requirement to disclose the identity of the person raising the concern, for example, under court disclosure rules.

There are practical steps that your organisation can take to protect the confidentiality of workers raising concerns. These include:

- ensuring that paper files are properly classified as confidential and held securely, and that electronic files are password protected;

- ensuring that the minimum number of people have access to case files;

- being discreet about when and where any meetings are held with the worker; and

- ensuring that confidential case papers are not left on printers or photocopiers.

As an employer you must ensure that, where the identity of the person raising a concern becomes known, they are protected and supported. Appropriate and timely action must be taken against anyone who victimises them.

The case example on page 24 of this guide (Lingard v HM Prison Service) demonstrates the potential consequences for an employer of not protecting the confidentiality of a worker.

Anonymity

A concern raised anonymously means that the person raising the concern does not reveal their identity to anyone. Your policy for raising concerns should not actively encourage anonymity because this makes it difficult to:

- investigate the concern;

- liaise with the worker;

- seek clarification or further information; and

- assure the worker and give them feedback.

Your organisation may still receive anonymous concerns and these should not be ignored. You still need to assess the information provided and take appropriate action in line with your organisation’s policy. Your policy should emphasise, however, that by making their identity known, workers are more likely to secure a positive outcome.

If your organisation receives a significant proportion of concerns anonymously, this may be an indication that your organisational culture is not open and ethical, and that cultural change is required.

Sir Robert Francis commented on this in his Freedom to Speak Up report:

“Anonymous concerns are not ideal but can add value. It is better to have information anonymously about a genuine issue than not have it at all…..

"However,…a high volume of anonymous reporting could be an indicator for a lack of trust in the organisation.”

How should my organisation deal with concerns?

“Many concerns are raised every day, and resolved quickly and informally. This should be encouraged wherever possible, provided it is done openly and positively.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

As an employer, you must take all concerns raised seriously. Some concerns, by their nature and scale, will require a more formal process of review and investigation than others. Your policy for raising concerns should set out the range of possible actions. The action you take will depend on the nature of each case, for example:

- Explaining the context of an issue to the person raising a concern may be enough to alleviate their worries.

- Minor concerns might be dealt with straight away by line management.

- A review by internal audit as part of planned audit work might be sufficient to address the issue e.g. through a change to the control environment.

- There may be a role for external audit in addressing the concerns raised and either providing assurance or recommending changes to working practices.

- There may be a clear need for a formal investigation.

Having considered the options, it is important that you clearly document the rationale for the way forward on the case file. Your policy for raising concerns should make clear whose responsibility it is to decide on the appropriate action to be taken.

If necessary you can also seek advice and guidance from the relevant prescribed person (see footnote 8).

Manage expectations

Page 26 of this Guide highlights to workers that, while they should expect their concerns to be taken seriously and given due consideration, not all cases will require a full investigation. Your policy should explain the possible courses of action that may be taken and, ideally, you should notify the person raising the concern as to what the proposed course of action will be.

Your policy should make clear to staff that when they raise a concern, they may not always get the outcome they want or expect. However, they should always expect to be taken seriously, and have confidence that the matter will be handled fairly and properly, in accordance with documented procedures.

“Any system needs to be as simple and free from bureaucracy as possible. However, it needs to provide clarity to the person who has raised a concern about what will happen next and how they will be kept informed of progress.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

How should we conduct a formal investigation if required?

“When a concern is raised, irrespective of motive, the priority must be to establish the facts fairly, efficiently and authoritatively….. How this is done will depend on how serious the issue is.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

It is important that investigations are undertaken by people with the necessary expertise and experience. If your organisation does not have such staff, you will need to consider engaging external resources.

Your internal auditors may be able to advise on this but may not be the best people to undertake the work if they do not have investigative qualifications. Where your internal auditors carry out investigations under your arrangements for raising concerns, and may also be involved in providing assurance on the effectiveness of those arrangements, any potential or perceived conflict of interest needs to be managed.

You should have documented procedures in place to be followed when conducting an investigation. These may be adapted from your fraud response plan or set out in a standard operating procedure.

Key considerations for any investigative process should include:

- employing investigators with the necessary skills;

- ensuring no conflict of interest between the investigator and the issue being investigated;

- having clear terms of reference;

- setting a clear scope for the investigation and drawing up a detailed investigation plan;

- clarifying what evidence needs to be gathered and how it will be gathered (document search, interviews etc.);

- deciding how best to engage with the person raising concerns and manage their expectations; and

- ensuring that all investigative work is clearly documented.

What does a good investigation look like?

In his review of the reporting culture in the NHS, Sir Robert Francis identified a number of factors essential to a good investigation process:

- The investigation should be done as quickly as possible to an agreed timetable. This should be set at the start and any changes should be notified to the person raising the concern.

- There must be a degree of independence, proportionate to the gravity and complexity of the issue being investigated. The investigator may be someone from a different part of the organisation who is independent of the issue being investigated. However, there may be circumstances where external independence would be desirable.

- The investigation must be conducted by appropriately qualified and trained investigators, who are given the requisite time to conduct and write up their investigation.

- The investigation must seek to establish the facts by obtaining accounts from all involved and examining relevant records.

- The investigation should result in feedback to the person who raised the concern.

- The investigation must be separate from any disciplinary process involving anyone associated with the concern, where possible.

- The outcome of the investigation should be considered at a level of seniority appropriate to the gravity of the issues raised, along with a programme of proposed action where relevant.

- Learning from the investigation should be shared across the organisation and beyond, where appropriate.

- Someone should keep in touch with the person who raised the concern at all times, to keep them abreast of progress and monitor their wellbeing.

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

Keeping contact and providing feedback

As part of the investigation plan, a reasonable level and frequency of contact should be agreed with the person who raised the concern. This will give them assurance that appropriate action is being taken in relation to the issue they raised. However, a person may want minimal contact once they have raised a concern and this should be respected.

In all cases, appropriate feedback should be provided to the person who raised the concern. This does not have to be comprehensive but should be sufficient to demonstrate that the concern has been properly considered and appropriately addressed. In his Freedom to Speak Up report, Sir Robert Francis said:

“Feedback to the person who raised the concern is critical. The sense that nothing happens is a major deterrent to speaking up…. there is almost always some feedback that can be given, and the presumption should be that this is provided unless there are overwhelming reasons for not doing so.”

How should we record, monitor and report caseload?

“Once a concern is raised formally, it is essential that organisations provide a straightforward system for logging them. This will…facilitate monitoring of trends and themes for organisational learning.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

Concerns raised by workers are an important source of information for your organisation. It is important that you capture key aspects of the concerns and the process for handling them, so that the value of your arrangements can be determined and lessons learned where appropriate. Government departments should have procedures in place for receiving information about concerns raised in all arm’s length bodies for which they are responsible. This can help identify concerns of a systemic nature.

Record

In addition to individual case files, your organisation should maintain a central record of all concerns raised, in a readily accessible format such as a database. Any system for recording concerns should be proportionate, secure, and accessible by the minimum number of people necessary.

The types of information recorded may include:

- the date the concern was raised;

- the nature of the concern and/or the risk highlighted;

- with whom the concern was initially raised;

- whether confidentiality was requested;

- the approach adopted (see page 42);

- who is investigating the concern;

- key milestone dates from the agreed investigation timetable;

- the outcome, in terms of whether the concern was founded or unfounded;

- whether feedback was given to the person raising the concern;

- whether the person was satisfied with the outcome and if not, why not; and

- the date the case was closed.

“Proper recording of formal concerns… aligns with the values of openness and honesty, by demonstrating a transparent approach to how they are handled.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

Monitor

Monitoring concerns raised has two important aspects: firstly, to ensure the handling of the concern is progressed in line with the agreed timetable and secondly, to facilitate data capture for management information purposes.

The central record of concerns should be periodically reviewed by a responsible officer and used to request updates on cases or generate reminders for action, as appropriate.

Analysis of the information captured will allow your organisation to identify trends or business risks which may need to be addressed, and will also provide useful management information on the operation of your procedures for raising concerns, such as:

- the number and types of concerns raised;

- how concerns were dealt with;

- the length of time taken to resolve concerns; and

- workers’ satisfaction with the procedures.

“There needs to be a clear process to ensure the concern is tracked and regularly reviewed; that it is dealt with quickly; and that there is no risk that it falls into a ‘black hole’.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

Report

In his review of arrangements in the NHS, Sir Robert Francis highlighted that in a number of high profile cases, senior management and the Board had not been aware of the scale and types of problems that existed in their organisation.

It is therefore essential that an analysis of concerns raised in your organisation, and the action taken in response to those concerns, is reported regularly to senior management, the Audit Committee and the Board. This will help inform those charged with governance that arrangements in place for workers to raise concerns are operating satisfactorily, or will highlight improvements that may be required. It will also provide them with assurance that appropriate steps have been taken, and lessons learned have been disseminated.

Your organisation’s annual report and accounts should include a section on concerns raised and improvements made in your organisation as a result. This will help demonstrate to staff that your organisation is open and transparent and that raising concerns yields results.

“Regular review by the CEO or his/her nominated board director will ensure that the senior leadership has full sight of issues within their organisation.”

Source: Freedom to Speak Up, February 2015

Is a small caseload a good thing?

Your organisation should not assume that a small number of concerns raised is a good thing; it could have a positive or negative interpretation. It could mean that your organisation is working well and that there are no matters of concern, or it could mean that workers are afraid to speak up or don’t know how to raise concerns. It is essential that your organisation has a clear policy of openness and that workers are made aware, and regularly reminded, of arrangements for raising concerns.

The Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RQIA), in its 2016 Review of the Operation of Health and Social Care Whistleblowing Arrangements in Northern Ireland, said:

“It is not acceptable for organisations to assume a low level of raising concerns is positive; they must ‘test the silence’ to gain assurance that the process of raising concerns is working well in their organisation.”

How do we know if our arrangements are effective?

“For a policy to be more than a tick-box exercise, it is vital that those at the top of the organisation take the lead on the arrangements and conduct a periodic review.”

Source: Protect (formerly Public Concern at Work (PCaW))

Arrangements for raising concerns must be effective, and must be seen to be effective, otherwise workers will be reluctant to speak up and your organisation will not have the opportunity to address issues before they have potentially serious consequences. It is not enough for your organisation to have a policy and procedures in place. You need positive assurance that your arrangements for raising concerns are working effectively.

The Committee on Standards in Public Life has recommended that well run organisations should review their arrangements for raising concerns, both to ensure their effectiveness and to confirm that workers have confidence in the arrangements.

Your Audit Committee has a key role in ensuring effective arrangements for raising concerns are in place. The Committee is part of the control environment of your organisation and should provide a challenge function when it receives management information about concerns raised (see page 47).

The Audit and Risk Assurance Committee Handbook provides some key questions which your Audit and Risk Committee should ask:

- How do we know that there are appropriate and effective practices in place for raising concerns?

- How do we know that these provide suitable channels for staff and others to raise their concerns?

- How do we know that the policies appropriately cover the issues of confidentiality and anonymity?

- How do we know that those raising concerns are offered appropriate support and provided with suitable and timely feedback?

- How do we know that concerns raised are dealt with properly and reported to senior management?

“A key determinant of the effectiveness of whistleblowing arrangements...is the willingness of the Board… to review arrangements, the extent to which they are trusted, awareness levels throughout the organisation… and how people who used the procedures were treated.”

Source: Committee on Standards in Public Life, January 2005

Supplementary questions to help answer the key questions may include:

- Is there evidence that the board regularly considers procedures for raising concerns as part of its review of the system of internal controls?

- Is there a comprehensive record of the number and types of concerns raised, follow-up action taken and the outcomes of investigations?

- Are there issues or incidents which have otherwise come to the board’s attention which they would have expected to have been raised earlier under the organisation’s procedures for raising concerns?

- Are there adequate procedures for retaining evidence in relation to each concern?

- Have confidentiality issues been handled effectively? Have there been any failures to maintain confidentiality?

- Is there evidence of timely and constructive feedback to the person raising the concern?

- Is there evidence of satisfactory feedback from individuals who have used the arrangements?

- Have any events come to the committee’s or the board’s attention that might indicate that a worker has been victimised or unfairly treated as a result of raising their concerns?

- Has there been a review of staff awareness, trust and confidence in the arrangements?

- Where appropriate, has internal audit performed any work that provides additional assurance on the effectiveness of the procedures for raising concerns?

Sources: Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales Guidance for Audit Committees – Whistleblowing arrangements, March 2004

PCaW - Whistleblowing Commission Report, November 2013

Benchmarking arrangements

Benchmarking your organisation’s arrangements for raising concerns against wider good practice and against similar organisations can highlight further improvements to be made.

The charity Protect, which provides advice and guidance to employers and workers about raising concerns, has developed a benchmarking tool to help organisations assess the effectiveness of their current arrangements. It has produced a set of standards under three key headings:

- Governance:

- Accountability

- Written policy and procedures

- Review and reporting

- Engagement:

- Communications

- Training

- Operations:

- Support and protection

- Recording and investigations

- Resolution and feedback.

Information on acquiring access to the benchmarking tool can be obtained by contacting Protect at business@protect-advice.org.uk or on 020 3455 2252.

Appendix 1 – Public Information Leaflet

Proper conduct of public business

Value for money

Fraud and corruption

RAISE CONCERNS

STOP WRONGDOING

Help ensure that public money, YOUR money, is spent properly, lawfully and safely.

Do you have a concern about the misuse of public money or wrongdoing by a public body?

If so, then raising a concern can be an important step towards ensuring that potential issues are identified and addressed.

Who should you contact?

As a member of the public, your first point of contact should be the government department or public body to which your concern relates. Contact details should be available on each organisation’s website.

However, if your concern is about:

- the proper conduct of public business

- value for money

- fraud and corruption

… in relation to central government, local government or health bodies, then an alternative point of contact is the Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO).

The NIAO is the office of both the Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland (C&AG) and the Local Government Auditor (LGA) and is independent of government.

Raising Concerns with the NIAO

How will the NIAO evaluate your concern?

If the issue you raise is within our remit, the NIAO will decide on the next steps based on:

- professional judgement;

- audit experience;

- whether there is a “public interest” element to the issue; and

- whether the concern indicates serious impropriety, irregularity or value for money issues.

The options for action can range from taking no further action, up to a full public report in the most serious cases. Other options include additional audit testing or referral to the relevant public body for investigation.

What can’t the NIAO do?

- The C&AG and the LGA do not have the power to discipline public service officials nor are they able to bring criminal prosecutions against such individuals.

- Disciplinary action can only be taken by management and/or any relevant professional bodies.

- Allegations of criminality are usually investigated by the police and can ultimately only be decided by the courts.

Will you have legal protection?

Legislation is in place to provide a remedy to workers who raise concerns about wrongdoing at work. It allows them to take their employer to an employment tribunal if they are victimised in any way as a result of raising a concern. As a member of the public, you have no employment relationship with the organisation about which you are raising a concern and so will not have, and will not need, this legal protection.

Will your identity be revealed?

When you raise a concern with the NIAO, it is preferable that you provide your name and contact details so that, if further action is proposed, we can contact you for further information, if required.

The NIAO treats all concerns raised with the utmost confidentiality. It will not reveal your identity to another organisation without consulting you first.

The NIAO will accept anonymous concerns and will evaluate them as outlined above. However, it may be more difficult to pursue the concern if we are unable to contact you for further information, if required.

How do you contact the NIAO?

Email: raisingconcerns@niauditoffice.gov.uk

Telephone: 028 9025 1000

Address: NI Audit Office

106 University Street

Belfast BT7 1EU

If your concern is outside the remit of the NIAO, we will aim to provide you with an alternative contact.

Appendix 2 – Legislative Protection

“It is important to reiterate that the Act is a statutory ‘backstop’…. Where an individual case reaches the point of invoking the Act then this represents a failure of the internal systems.”

Source: Committee on Standards in Public Life, 10th Report, January 2005