Abbreviations

BCC Belfast City Council

DAERA Department of Agriculture Environment and Rural Affairs

DfC Department for Communities

DfI Department for Infrastructure

EIA Environmental Impact Assessment

EU European Union

FTE Full-time equivalent

IE Independent Examination

LDP Local Development Plan

LPP Local Policies Plan

NI Northern Ireland

NICS Northern Ireland Civil Service

NIEA Northern Ireland Environment Agency

PAC Planning Appeals Commission

PAD Pre-application discussion

PAN Planning Advice Note

PPS Planning Policy Statement

PS Plan Strategy

RDS Regional Development Strategy

RTPI Royal Town Planning Institute

SES Shared Environmental Service

SPPS Strategic Planning Policy Statement

Executive Summary

The planning system should positively and proactively facilitate development that contributes to a more socially, economically and environmentally sustainable Northern Ireland

1. The planning system has the potential to make an important contribution to much needed development in Northern Ireland. When it works effectively, it can have a key role in encouraging investment and supporting the Northern Ireland economy, creating places that people want to work, live and invest in. The system also has the potential to act as a key enabler for the delivery of a number of draft Programme for Government outcomes.

2. Delivering an effective system provides potential investors with the confidence they need to propose development in Northern Ireland and ensure that it is sustainable and meets the needs of the community.

3. Despite the importance of the planning system to Northern Ireland, our review found that it is not operating effectively, not always providing the certainty that those involved wanted, and in many aspects not delivering for the economy, communities or the environment.

The way in which planning functions are delivered fundamentally changed in 2015

4. The Planning Act (NI) 2011 (the Act) established the two-tier system for the delivery of planning functions in Northern Ireland. Under the Act, responsibility for delivering the main planning functions passed from a central government department to local councils in April 2015.

5. The Department for Infrastructure (the Department) has responsibility for preparing regional planning policy and legislation, monitoring and reporting on the performance of councils’ delivery of planning functions and making planning decisions in respect of a small number of applications.

The planning system has not met many of its main performance targets

6. Since the transfer of functions to local government, on a number of key metrics, the planning system in Northern Ireland has not delivered against many of its main targets. Around 12,500 planning applications have been processed each year in Northern Ireland since 2015. Despite their importance, processing the most important planning applications still takes too long.

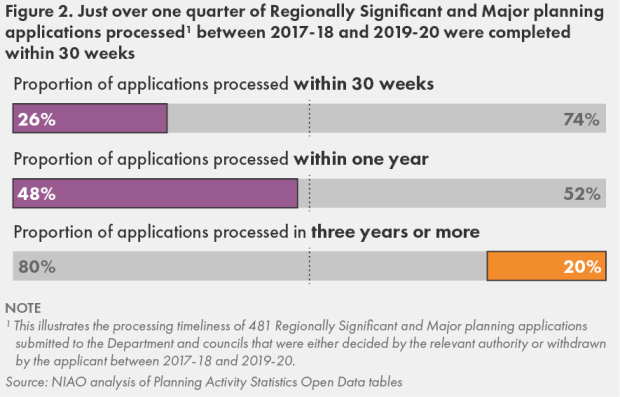

7. Major planning applications can relate to development that has important economic, social or environmental implications. Despite a statutory target for each council to process major development planning applications within an average of 30 weeks, the vast majority of Major planning applications take significantly longer. Around one-fifth of these applications take more than three years to process.

8. The Department told us that the period following the transfer of planning powers to local government in 2015 was dominated by a lack of a local Assembly and ministers for three years to January 2020, the implications of the Buick judgment in 2018 for decision-making, followed by the significant impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and, as a consequence, there was an impact on the performance of the system.

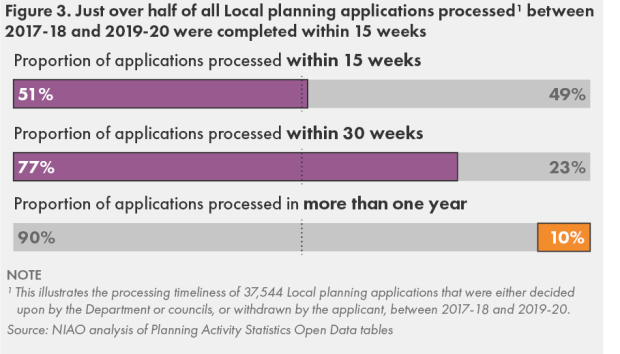

9. Performance on Local applications is better. The target, that Local development planning applications will be processed within an average of 15 weeks, was achieved for Northern Ireland as a whole in both 2018-19 and 2019-20. Performance dipped in 2020-21, but this was likely caused by the impact of Covid-19.

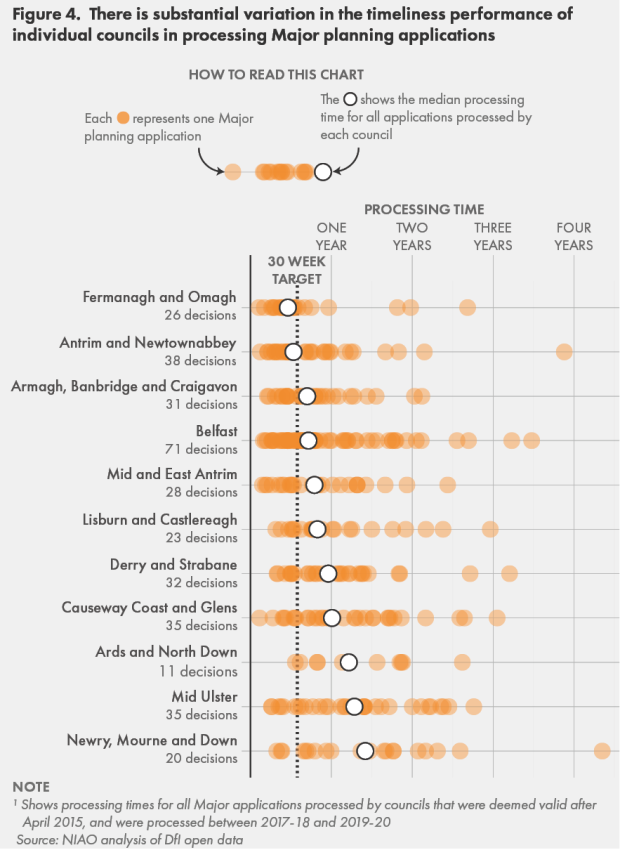

10. Our analysis shows that the time taken to process Major applications varies substantially between councils. For Major planning applications processed between 2017-18 and 2019-20, the median processing time for the slowest council was more than three times that of the fastest council.

Despite the importance of planning, the system is increasingly financially unsustainable

11. When planning responsibilities transferred to councils, it was on the basis that delivery of services should be cost neutral to local ratepayers at the point of transfer. However, the income generated from planning does not cover the full cost of service delivery. The fees councils charge for planning applications are decided by the Minister for Infrastructure and were initially set by the Department in 2015, with individual rates for different types of planning application. In the absence of a Minister from January 2017 to January 2020, the Department was able to raise fees once (by around 2 per cent, in line with inflation in 2019) following the enactment of the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation and Exercise of Functions) Act 2018, which allowed the Department to take certain decisions normally reserved to the Minister.

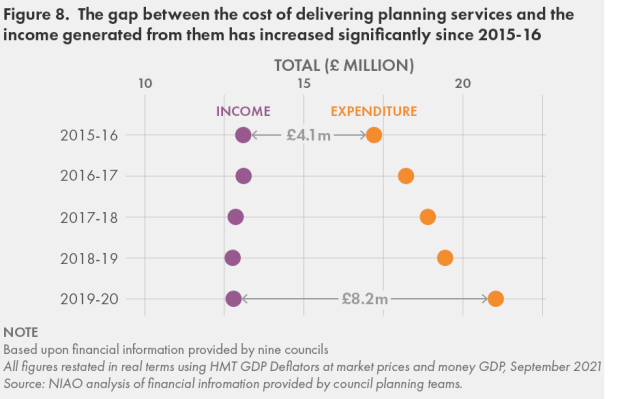

12. As a result, there has been a need to supplement income with other public funding to deliver planning services. Our review of financial information provided by councils showed that the gap between income generated by planning activities and the cost of those activities increased significantly between 2015-16 and 2019-20. This is not sustainable in the longer term.

The system is inefficient and often hampered by poor quality applications

13. There is a low bar for the quality of planning applications that are allowed to enter the system. Stakeholders consistently told us that the criteria set out in the 2011 Planning Act are too narrow, and do not require applicants to provide key supporting documentation. This means the Department and councils are often obligated to attempt to process poor quality and incomplete applications.

14. Whilst some councils have taken steps to improve application quality, such as the creation of application checklists, these have not been rolled out across the system. We highlighted the issue of poor quality applications in our previous report on Planning in 2009. The Department told us that it is proposing to take forward legislative changes to better manage the quality of applications and it has encouraged councils to roll out an administrative checklist in advance of any legislative change.

There is an urgent need for improved joined-up working between organisations delivering the planning system

15. Our review has identified significant silo working within the planning system. We saw a number of instances where individual bodies – councils, the Department or statutory consultees – have prioritised their own role, budgets or resources, rather than the successful delivery of the planning service. Each organisation is accountable for its own performance, and whilst the Department monitors the performance of individual organisations against statutory targets, there is little accountability for the overall performance of the planning system. Whilst individual organisations stressed the challenges they faced, ultimately the frustration from service users was the poor performance of the system, not issues in individual bodies.

16. In our view, the ‘planning system’ in Northern Ireland is not currently operating as a single, joined-up system. Rather, there is a series of organisations that do not interact well, and therefore often aren’t delivering an effective service. This has the potential to create economic damage to Northern Ireland. Ultimately, as it currently operates, the system doesn’t deliver for customers, communities or the environment.

17. In our view, this silo mentality presents both a cultural and a practical challenge. The focus for all of those involved in the system must be the successful delivery of planning functions in Northern Ireland, not the impact on their own organisations. This will require strong, consistent leadership – in our view the Department is well placed to provide this and should continue to build on its work to date. It is crucial that all statutory bodies involved in the planning system play their part and fully commit to a shared and collaborative approach going forward.

Many statutory consultees are struggling to provide information in a timely manner

18. Processing an individual planning application often requires technical or specialist knowledge that doesn’t exist within individual council planning teams. In these cases, statutory consultees provide officials with information they need to inform their decision. Whilst councils ultimately decide on planning applications, the fact that the majority of consultees sit outside local government adds another layer of complexity to an already fragmented system.

19. Statutory consultees are required to make a substantive response to planning authorities within 21 days or any other period as agreed in writing with a council. Performance is consistently poor, particularly in respect of Major planning applications. The poorest performance is by DfI Rivers, part of the Department for Infrastructure, which only responds in time to around forty per cent of all consultations. The Department told us that that there has been a major increase in consultations received by statutory consultees. This, coupled with the increasing complexities of cases received and finite resources, has had significant implications in relation to performance. Nonetheless, there is room for improvement in the timeliness of responses from most statutory consultees.

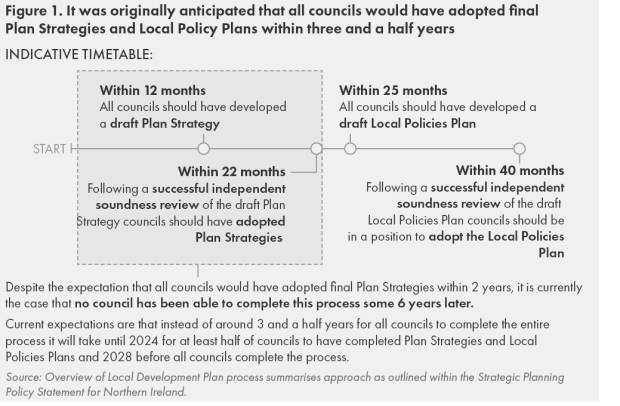

The system isn’t meeting its plan-making objectives

20. Northern Ireland’s planning system is intended to be “plan-led” and each council is preparing a Local Development Plan (LDP). The Department’s expectation was that all councils would have a fully completed LDP within three and a half years of beginning the process. However, six years later, no council has managed to complete an LDP, with many still in the early stages of the process. The Department told us that this was an indicative timetable, which sought to provide an estimate under a new and as yet untested system. The legislation provides for amended timetables to be submitted.

21. Despite the slow progress, estimates provided to us on the total spend to date on development of LDPs ranged from £1.7 million to £2.8 million per council, figures that would be equivalent to the total annual cost of delivering planning functions within most councils.

The planning system faces challenges in effectively managing applications which have the potential to have a significant impact on the environment

22. Preserving and improving the environment is one of the core principles of the planning system. However, a number of stakeholders highlighted the increasing challenges of assessing and managing the environmental impact of proposed development. Environmental assessments required for individual applications are often complex and time-consuming.

23. We heard concerns that the planning system is struggling to progress some complex planning applications which can include environmental impact assessments. In particular, there is a lack of certainty around how the system deals with applications for development that will produce ammonia emissions. The lack of clear environmental guidance in this area creates significant uncertainty for planning authorities, applicants and statutory consultees. The system urgently needs updated policy guidance from the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs.

Value for money statement

In our view, the planning system is not operating efficiently. Crucially, in many aspects, the system doesn’t deliver for the economy, communities or the environment. NIAO regularly receives concerns about planning decisions, implying a lack of confidence in the way the system operates. In addition, costs consistently exceed income, and the system itself is being subsidised by both central and local government. It is simply unsustainable to continue in this way.

Part One: Introduction

1.1 The objective of the planning system is to secure the orderly and consistent development of land whilst furthering sustainable development and improving wellbeing. By directing and controlling the type and volume of development that occurs, the system can support the sustainable creation of successful places in which people want to live, work and invest. As the planning system can be a key enabler for achieving many of the economic and social outcomes targeted within the draft Programme for Government outcome framework, it is vital it operates effectively.

There are a large number of public bodies involved in delivering the planning system in Northern Ireland

1.2 The Planning Act (NI) 2011 (the Act) established a two-tier structure for the delivery of planning functions in Northern Ireland. The Department for Infrastructure (the Department) has a central role in the planning system in Northern Ireland. Alongside this, it has responsibility for preparing planning regional policy and legislation, and monitoring and reporting on the performance of councils’ delivery of planning functions. In addition, the Department makes planning decisions in respect of a small number of Regionally Significant and called-in applications.

1.3 Under the Act, responsibility for delivering the majority of operational planning functions passed from a central government department to local councils in April 2015. This includes:

- development planning – creating a plan that sets out a vision of how the council area should look in the future, by deciding what type and scale of development should be encouraged and where it should be located;

- development management – determining whether planning applications for particular development proposals should be approved or refused; and

- planning enforcement – investigating alleged breaches of planning control and determining what action should be taken.

1.4 The ability of councils to deliver these functions often depends upon expert advice provided by a number of statutory consultee organisations. These are mainly central government organisations that provide specialist expertise to council planning officials on technical matters relating to individual planning applications, or on issues relating to development plans. The main organisations that councils consult with are Department for Infrastructure (DfI) Roads, Department for Agriculture Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA), DfI Rivers, NI Water and the Historic Environment Division within the Department for Communities, but there are a number of others.

1.5 In most cases, consultations are required to meet a statutory obligation. These consultations are referred to as statutory consultations. In addition, there are a large number of non-statutory consultations, which have increased in recent years.

The planning system has not met many of its main performance targets in recent years

1.6 Two of the main functions of the planning system are to establish plans that should control the volume and type of development that will occur, and then to efficiently process development applications, approving or refusing these. Since 2015, the planning system has not met many of its main performance targets.

1.7 Under the Act, each council was required to develop a Local Development Plan that would direct and control development in their area. The Department estimated that all councils would have such plans in place by 2019. The Department told us that this was an indicative timeframe that sought to provide an estimate for the preparation of a plan under the new, and as yet untested, system.

1.8 However, no council has been able to complete a plan. As a result, planning decisions made by planning authorities often refer to plans and policies that are old and do not reflect the current needs and priorities of the area. The Department told us that in such cases the weight to be afforded to an out-of-date plan is likely to be reduced and greater weight given in decision-making to other material considerations such as the contents of more recent national policies or guidance.

1.9 The planning system has also struggled to achieve efficient and timely processing of the Major development applications it receives. In particular, there has been a consistent failure to process the most important development applications in line with the timeliness targets set for these applications, with little evidence of improvement in performance forthcoming.

1.10 The Department told us that the period following the transfer to local government in 2015 was dominated by a lack of a local Assembly and ministers for three years to January 2020, the implications of the Buick judgement in 2018 for decision-making, followed by the significant impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and, as a consequence, there was an impact on the performance of the system.

1.11 An effective and efficient planning system can facilitate significant investment into Northern Ireland, which can have wider effects on the economy, including the creation of jobs and economic growth. A poorly performing planning system, however, can bring delays, costs and uncertainty which either postpone economic benefits or, in the worst circumstances, undermine proposed investment. The Department told us that timeliness is only one aspect of performance as it is important that the right decisions are made, supported by sufficient evidence and appropriate consultation.

Variances in decision-making processes across different council areas represent a risk to efficiency and effectiveness

1.12 The transfer of responsibilities under the Act granted councils a certain degree of flexibility in how they design their own arrangements for delivering planning functions. This flexibility was intended to give councils the power to design their processes in a way that best suited local needs, and to empower councils to shape how development occurred within their area, in line with the aspirations of the local community.

1.13 Prior to the transfer of planning to councils in 2015, the Department developed a best practice protocol for the operation of planning committees setting out a framework of principles and good practice that planning committees should adhere to. The Department told us that this protocol was not mandatory, but it recognised that there should be a degree of consistency across the eleven councils.

1.14 Our review of available data and engagement with various stakeholders has suggested that there are risks that all councils are not complying with best practice standards in respect of decision-making, and that approaches are characterised by a high level of variance, with no strong evidence that this variance is delivering additional value.

Councils’ ability to perform effectively can be constrained by issues beyond their direct control

1.15 Whilst councils have primary responsibility for the operational delivery of most planning functions, there are a number of external constraints, often beyond the control of councils that have had a negative impact on their ability to deliver effectively. These include:

- that adequate resources were not provided to allow councils to deliver all the functions for which they are responsible;

- that statutory consultees are able to provide timely responses to councils when requested to provide advice on issues relating to a particular application; and

- that there are effective arrangements in place to monitor the overall performance of the planning system and to support the effective management of issues that are affecting the quality of the service delivered.

1.16 We found deficiencies within each of these areas that affect the quality of the service currently being delivered which, if not addressed, pose significant risks to the future delivery of services.

Scope and structure

1.17 In this study we undertook a high level review of how effectively the planning system was operating, and how effectively it was being governed. We undertook a detailed analysis of available data covering the performance of the planning system in a variety of areas, and engaged with a broad range of stakeholders both inside and outside the system.

1.18 The remainder of this report considers:

- a summary of how the planning system has performed since 2015 in respect of its three main functions (Part Two);

- concerns about how decisions are made within councils (Part Three);

- how the Department exercises the functions assigned to it within the Planning Act (Part Four); and

- some of the wider strategic issues that are having a significant impact upon the effectiveness of the planning system (Part Five).

Part Two: Performance of the planning system

2.1 Northern Ireland’s planning system is intended to be a “plan-led” system. Policies and priorities should be clearly set out in a framework of development plans that establish the volume and type of development that will be allowed. These plans will allow developers to assess the type of development proposals that will be accepted or refused, and provide a basis for transparent decision-making by planning authorities. The integrity of this system is protected by an enforcement system that ensures that all development is within the terms of the planning permission granted by planning authorities.

Plan-making

Each council is responsible for the creation of a Local Development Plan

2.2 Under the 2011 Act, each council was made responsible for the preparation of a Local Development Plan (LDP) – a 15 year framework document that would direct and control the scale and type of development that would be undertaken within the council area. The vision and objectives of the LDP should reflect the spatial aspirations of the council’s Community Plan. Each LDP should consist of two main documents:

- A Plan Strategy (PS) is the first stage of an LDP. It provides the strategic framework for key development decisions that will be made in the council area. The legislation provides that any determination made under the 2011 Act must be made in accordance with the plan, unless material considerations indicate otherwise . In preparing the LDP a council must take account of the Regional Development Strategy (RDS) and any policy or advice such as the Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS).

- The PS will be supplemented by a Local Policies Plan (LPP) setting out local policies and site specific proposals for development, designation and land use zonings to deliver the council’s vision, objectives and strategic policies. The LPP is required by the legislation to be consistent with the Plan Strategy.

2.3 The process by which each document is prepared is prescribed by legislation. Under the Local Development Plan process, the Department has an oversight and scrutiny role. As part of this, a council is required to submit its LDP document to the Department to ensure that it is satisfactory. The Department will then cause an Independent Examination (IE) to be carried out by an independent examiner, usually the Planning Appeals Commission (PAC) . Following the IE, the examiner will issue a non-binding report of its findings to the Department which will in turn consider this and issue a binding direction to a council. A council must incorporate any changes outlined in the direction and subsequently adopt the Plan Strategy.

Six years into the process, no council has an approved Plan Strategy

2.4 The expectation was that all councils would have a fully completed LDP within three and a half years of beginning the process. However, six years later no council has managed to complete an LDP, with most still only having a draft Plan Strategy in place. The most recent projections provided by councils suggest that it will be 2028 before there is an LDP in place in each council area (see Figure 1). Some councils currently project that they will complete the LDP process over the next two to three years. However, a number of them are still in the early stages of the process, so these projections may be overly ambitious.

2.5 The Department told us that the indicative timeframe of three and a half years sought to provide an estimate for the preparation of a plan under a new, and as yet untested, system. The legislation, however, provides for amended timetables to be submitted and agreed by the Department and this reflects and acknowledges the reality that timetables could be subject to further change.

2.6 Our discussions with councils highlighted a number of issues with the LDP process:

- The Department’s indicative timetable set for completion was too ambitious, given the scale and complexity of the work required by councils.

- A number of council planning teams did not have staff members with experience of plan development or expertise in the specialist areas required to develop their plan.

- Resource pressures in many councils mean that staff are often removed temporarily from LDP development work to manage short term pressures in application processing.

These issues are all discussed in more detail in Part Three of the report.

The lack of LDPs means planning decisions are not guided by up-to-date plans

2.7 Planning decisions must be made in accordance with the LDP unless material considerations indicate otherwise. In the absence of newly developed LDPs, councils must make planning decisions with reference to the existing local policies that are in place and all other material planning considerations. In some cases, the plans covering particular parts of a council area are over 30 years old, and do not reflect the current needs and priorities of the area.

2.8 The Department told us that in such cases the weight to be afforded to an out-of-date plan is likely to be reduced and greater weight given in decision-making to other material considerations such as the contents of more recent national policies or guidance. The weight to attach to material considerations in such circumstances is however a matter for the decision taker. Some stakeholders told us that older plans were potentially more open to interpretation than newer plans, increasing the risk that decision making is not consistent within or between councils, or that the rationale for the decisions is not clear to the public.

2.9 Where the existing plans do not provide adequate guidance, decision-makers must refer to other material planning considerations such as national policy set out in the Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS) or Planning Policy Statements (PPSs). These PPSs were retained as a temporary measure as part of transitional arrangements to ensure continuity of policy for taking decisions until the adoption by councils of a Plan Strategy for their area. PPSs were initially developed by the former Department of the Environment and set out regional Northern Ireland-wide policy on particular aspects of land use and development. However, we have been told they are complex, disparate and, because they were never intended to be specific to local areas, it can be challenging to make specific local decisions based upon them, although all of this was also the case under the unitary system.

2.10 One of the objectives of developing LDPs was to translate this framework of regional policy into a more operational local policy framework tailored to local circumstances and based on local evidence. The Department told us that it prepared the SPPS which consolidates and retains relevant strategic policy within PPSs. In preparing LDPs councils must take account of the SPPS, the Regional Development Strategy and any other guidance issued by the Department. Councils told us that it was only after the introduction of the SPPS in September 2015 that councils became aware of the need to review and incorporate 23 regional policy documents at the draft plan strategy stage. Councils told us this required significant additional time and resources.

Despite the lack of progress, councils report having invested significant time and resources on developing plans

2.11 During our engagement with council planning teams, there was a unanimous view that the amount of work required to prepare LDPs had been significantly underestimated by the Department’s indicative timeframe of 40 months. The Department told us that this provided an estimate for the preparation of a plan under the new and as yet untested system. Developing a full plan requires each council to follow four key stages set out by the Department:

- initial Plan preparation, including producing a preferred options paper;

- preparation and adoption of plan strategy;

- preparation and adoption of local policies plan; and

- monitoring and review.

During this process councils are required to consult a variety of stakeholders and provide commentary on plans developed by neighbouring councils.

2.12 Estimates of the total spend to date incurred on the development of LDPs ranged from £1.7 million to £2.8 million per council – figures that would be equivalent to the total annual cost of delivering planning functions within most councils. Given the scale of the investment required to develop LDPs, it is critical that they are accepted by all stakeholders as providing value.

2.13 In our view, there is an opportunity for the Department to review the LDP process, learning from the challenges experienced to date, and consider whether the process is proportionate and will provide value for all stakeholders. Councils told us that the current LDP process is too slow to respond to rapidly evolving issues such as climate change, energy and public health and needs to be more agile to respond to these challenges.

Recommendation

We recommend that the Department and councils work in partnership to review the current LDP timetables to ensure they are realistic and achievable, and identify what support councils need to meet them.

The Department may wish to consider whether the remaining steps of the LDP process could be further streamlined to ensure plans are in place as soon as possible.

Decision-making

Almost one-fifth of the most important planning applications aren’t processed within three years

2.14 Around 12,500 planning applications have been decided or withdrawn each year in Northern Ireland since 2015. These applications are classified according to the scale of the development proposed, and its impact on society. The most important applications, in terms of their ability to enhance the overall wellbeing in Northern Ireland, are ‘Regionally Significant’ and ‘Major’ planning applications. Regionally Significant applications are those applications which are considered to have a critical contribution to make to the economic and social success of Northern Ireland as a whole, or a substantial part of the region. These applications are submitted to, and processed by, the Department.

2.15 Major developments are those developments which have the potential to be of significance and interest to communities. They are likely to be developments that have important economic, social and environmental implications for a council area. Major developments which are considered Regionally Significant have the potential to make a significant contribution to the economic, societal and environmental success of Northern Ireland. They may also include developments which potentially have significant effects beyond Northern Ireland or involve a substantial departure from a LDP. In certain circumstances the Department may call-in a particular Major planning application, meaning that it assumes responsibility for making a decision on the application. There is a statutory target for councils to process Major development decisions within an average of 30 weeks of a valid application being received. Despite this, the vast majority of Regionally Significant and Major planning applications take significantly longer than 30 weeks to process, and there is a substantial subset of applications that take excessively long to process (see Figure 2). We found a similar trend in respect of the ages of outstanding Regionally Significant and Major applications at 31 March 2021. Over half (56 per cent) had been being processed for more than one year, with 19 per cent more than three years old. Factors impacting on the performance of the system are considered further in Part Five .

2.16 The Department told us that the absence of an Executive and a functioning Assembly has had an impact on its ability to make key changes and decisions. The ٢٠١٨ Court ruling in Buick prevented planning decisions being made by the Department until legislation was enacted which allowed senior civil servants to take certain decisions. With the return of the Executive, the Department told us that the ruling has continued to have impacts on planning. In addition, whilst performance could be improved, poor quality planning applications entering the system and increased requirements under environmental regulations have also impacted the timeliness for processing Major and Regionally Significant applications.

2.17 Applications that are not classified as Regionally Significant or Major are classified as Local. These are the vast majority of applications decided in a given year – typically 99 per cent. They are submitted to and determined by councils, with a statutory target to be processed within an average of 15 weeks from the date of a valid application.

2.18 Whilst councils hadn’t achieved this standard in the first two years after powers were transferred, performance has been much stronger over the last three years and the target was achieved for Northern Ireland as a whole in both 2018-19 and 2019-20. Over the three year period 2017-18 to 2019-20, 52 per cent of local applications were processed within the 15 week target (see Figure 3). Performance dipped in 2020-21, but this may have been due to Covid-19 disruption.

Whilst comparison of planning performance across the UK is challenging, it appears that the planning system in Northern Ireland is slower than in other jurisdictions

2.19 A direct comparison of performance data between planning systems in different countries is challenging because of the differences in the way different countries measure and report performance. However, the comparisons we were able to make highlighted that the planning system appears to be slower in dealing with Local applications in Northern Ireland than in other jurisdictions. For example:

- In England, over 60 per cent of non-major planning applications were processed within 8 weeks in 2018-19 and 2019-20, compared to less than 30 per cent of local applications in Northern Ireland over the same period.

- In Scotland, the average processing time for local planning applications was 10 weeks during 2018-19 and 2019-20, compared to 18 weeks in Northern Ireland over the same period.

- In Wales, 89 per cent of local planning applications were processed within 8 weeks, compared to 18 per cent in Northern Ireland in the same year.

2.20 The Department told us that there are significant differences in how each planning system works, how performance is measured and the political and administrative contexts in which they operate. It is, therefore, difficult to assess the functionality and performance of the planning system in Northern Ireland against that of other jurisdictions. All jurisdictions have definitions of types of development that are permitted without the need for a planning application; an appeal system to review decisions on applications; and a system in place to enforce breaches of planning consent. Although the basic structures of the planning system in each jurisdiction are similar there are differences in the detail and in how each system works. For example; in terms of performance ; KPIs are measured differently in jurisdictions. In some jurisdictions time extensions can be given to planning applications which in effect ‘stops the clock’. This does not occur here. In England in the event minimum standards are not met, a local authority may be designated as underperforming with special measures applied that allow applicants for major development to apply for permission direct from the Planning Inspectorate, bypassing local decision-making. This does not occur here.

There is substantial variation in timeliness performance within Northern Ireland

2.21 There is substantial variation in the performance of individual councils in processing applications. As service users must submit planning applications to the council responsible for the area in which the proposed development is located, there may be a risk that this leads to different qualities of service being offered.

2.22 However, a number of councils we spoke to highlighted their concerns that straightforward comparisons of processing times were unfair, and did not provide useful insight about relative performance levels. They stressed that differences in the mix of applications that each council receives has a material impact on processing times but is outside the control of councils. Major agricultural and residential development applications were typically highlighted as being particularly complex and requiring significant time to effectively assess. A further issue related to the impact of pre-2015 applications inherited by councils on transfer of functions. The Department told us that legacy cases had reduced significantly after the first two years post-transfer.

2.23 However, service users we spoke to stated that whilst they accepted there were factors beyond the control of councils, it was still the case that differences in processing time performance did to some degree reflect differences in process and approach between councils.

2.24 As part of our analysis, we applied a number of adjustments to the underlying data in an attempt to make timeliness comparisons between councils fairer. Whilst we agree that there is evidence that major residential and agricultural proposals typically take longer than other types of planning application, we did not find that these were concentrated within certain council areas to the extent they would have a significant impact on median processing times.

2.25 Even after the adjustments we applied to the data, we found that there was substantial variation in respect of the time taken to process major applications between councils. For Major planning applications processed between 2017-18 and 2019-20, the median processing time for the slowest council is more than three times the median processing time for the fastest council (see Figure 4).

2.26 Whilst the Department regularly reports on the performance of each council, we did not find evidence that this information is used in any meaningful way to improve performance or hold bodies accountable for poor performance. The lack of general buy-in to the current performance monitoring process amongst councils is also concerning and undermines the accountability that such information should provide. This is part of a wider issue in terms of performance measurement and reporting that is discussed in more detail at paragraphs 4.23 to 4.35 .

2.27 The Department told us that it has worked with councils through various groups over the years, such as the Strategic Planning Group, Continuous Improvement Working Group and Planning Forum in order to improve performance.

Recommendation

We recommend that the Department and councils continue to put an enhanced focus on improving the performance of the most important planning applications. This should include a fundamental analysis of the factors contributing to delays.

There is significant variation in how enforcement cases are resolved

2.28 Enforcement is the means by which planning authorities ensure that the development that occurs is in line with policies and within the terms of the planning application approved in respect of the project. Effective enforcement is critical for both ensuring that the planning system is able to control development, and that the credibility and integrity of the system are not undermined by unauthorised development.

2.29 Responsibility for undertaking enforcement activity rests primarily with councils. Each council is responsible for undertaking enforcement activity in its area, and there is a statutory target that 70 per cent of enforcement cases are taken to target conclusion within 39 weeks of the initial receipt of a complaint.

2.30 Despite a substantial increase in the volume of enforcement cases being opened, performance against the statutory target by councils has been good. The volume of cases increased by almost 50 per cent between 2015-16 and 2019-20 – from 2,900 to 4,300. Over this period, most councils have been able to meet the target in each year, with only a small number failing in a single year and one council consistently unable to meet the target.

2.31 However, during our engagement with council planning teams, a number told us that staffing resources were often diverted from enforcement to meet short-term pressures in processing planning applications or progressing LDPs. We also note that the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) has referred to concerns about the severe underfunding of planning enforcement departments, and the potential for this to contribute to an inability to investigate all the cases that should be investigated or a lack of rigour in those investigations that do occur.

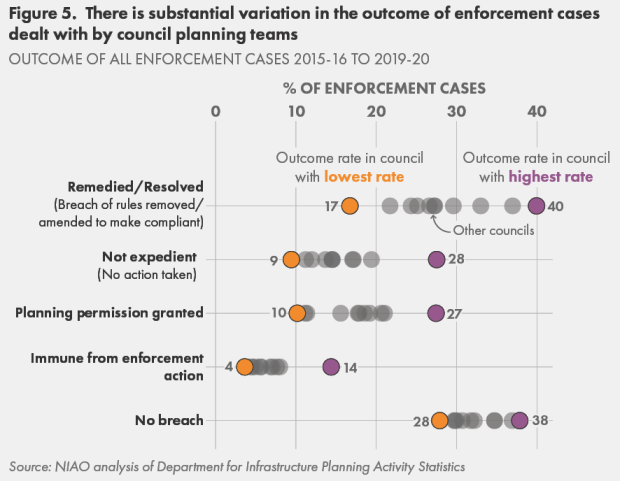

2.32 As part of our analysis, we reviewed trends in enforcement case outcomes, and found substantial variation in respect of outcome types across councils. In some cases, a particular outcome type could be around three times more common in one council than another (see Figure 5). For example, in one council, around one in four enforcement cases (28 per cent) were deemed not expedient to pursue, compared to a rate of 9 per cent in another council.

2.33 Given this context, there is a risk that significant variations in outcome types may indicate that certain outcomes are prioritised for their operational efficiency rather than being the most appropriate outcome. This risk seems relevant to the significant differences in the proportion of enforcement cases where councils have deemed it not expedient to take further action, have granted planning permission or where it is determined the issue has been remedied or resolved, (i.e. the breach of planning rules has been removed or amended to make compliant with rules). This may result in uneven enforcement of planning rules, meaning unauthorised development may be allowed to occur.

2.34 Councils told us that the enforcement system in Northern Ireland is a discretionary power of the planning authority, and what may be considered as not expedient in one council, possibly due to the volume of work or lack of resource, may be pursued by another council. Actions taken are also often based on case law, PAC decisions and likelihood of success.

2.35 We did not find evidence of any substantive review of these trends to determine whether the significant variations that were evident were reasonable or natural. In our view, there is a risk of inconsistency in enforcement which may have a negative impact on how fairly the system is operating.

Recommendation

To ensure credibility within the system, we recommend that the Department and councils investigate differences in enforcement case outcomes, to ensure cases are being processed consistently across Northern Ireland.

Part Three: Variance in decision-making processes

3.1 Councils are responsible for processing the vast majority of planning applications submitted in Northern Ireland. While decision-making responsibilities within each council are split between the planning committee – a body made up of between 12 and 16 elected representatives - and professional planning officials employed by the council, it is ultimately the council who is responsible for the planning function.

Delegation arrangements are an essential part of an effective development management process

3.2 Given that councillors are not typically professional planners, the sharing of decision-making roles and responsibilities between planning committee members and officials can make a critical contribution to the efficiency and effectiveness of decision-making processes within an individual council.

3.3 There are a small number of application types that must be decided by the planning committee in all councils:

- all Major planning applications;

- applications made by the council or an elected member; and

- applications that relate to land in which the council has an estate.

3.4 For all other Local application types, each council must operate a Scheme of Delegation. A Scheme delegates planning decision making authority from a planning committee to planning officials in a council for chosen classes of local development applications and any application for consent, agreement or approval required by a condition imposed on a grant of planning permission for a local development. These aspects of a Scheme are subject to the approval of the Department. However, there are many other types of applications that are not local developments that can form part of a Scheme which are not subject to the Department’s approval such as listed building consent, conservation area consent applications and tree preservation orders.

3.5 Whilst councils have been granted some flexibility in tailoring their specific arrangements to best meet local needs, Schemes of Delegation should ensure that decisions are taken at an appropriate level – only the most significant or controversial applications should be considered by committee. Furthermore, councils should ensure that their delegation processes are clear, transparent and efficient. The Department also intended that, despite local variation, there is at least some degree of consistency, to ensure that applicants across Northern Ireland are not confronted by a variety of different processes across different council areas.

Not all Schemes of Delegation ensure that decisions are taken at an appropriate level

3.6 Departmental guidance, published in 2015, recommended that over time councils should aim to have between 90 and 95 per cent of applications dealt with under a scheme of delegation, however this is not a statutory target. At the time we carried out our fieldwork, data was available showing delegation rates for each council for the 2018-19 and 2019-20 years. During these two years, the overall delegation rate across all councils was 91 per cent. In eight councils, delegation rates fell within the 90 to 95 per cent range in both years, but in three councils, rates fell below the range in both years.

3.7 The Scheme of Delegation in all three councils which fell below the target range required all applications refused by officials to be referred to the planning committee, regardless of nature or scale. This inevitably resulted in a higher proportion of applications being considered at committee level.

3.8 It is not clear that limiting delegation in this way contributes to better quality decision-making. Departmental guidance is clear that regardless of local arrangements, and allowing for individual applications to be referred to committee upon the request of planning committee members, councils should ensure that applications are not unnecessarily referred to the planning committee, as this will contribute to inefficiency and delay. Councils told us that whilst they acknowledge that this may impact timeliness, it is the prerogative of committee members to use this mechanism.

3.9 The current processes in the councils referred to in paragraph 3.7 appear contrary to Departmental guidance and the policy objectives that committees should invest their time and energy only in the most significant or controversial applications. Such processes are likely to contribute to additional costs within these council areas. A benchmarking exercise carried out in England in 2012 highlighted that there are significantly higher administrative demands and costs associated with applications heard by committee as opposed to those decided by officials.

Recommendation

We recommend that in instances where delegation rates fall below 90 per cent, councils should review their processes to ensure that they represent the best use of council resources.

The type of applications being considered by committees are not always appropriate

3.10 Our analysis of available data and information from stakeholders suggests that there are widespread concerns that the specific applications coming to committee, either under the normal Scheme of Delegation arrangements or by referral, are not always the most significant and complex applications. In particular, some council planning committees appear to be excessively involved in decisions around the development of new single homes in the countryside.

3.11 We analysed planning applications processed in 2018-19 and 2019-20. During this period, across Northern Ireland, planning applications for single rural dwellings accounted for around 16 per cent of all applications processed. Despite often being relatively straightforward applications, they accounted for 18 per cent of all planning committee decisions in the same period. Within these overall figures, there are wide divergences at council level (see Figure 6).

| COUNCIL | NEW SINGLE RURAL DWELLINGS AS % OF... | DIFFERENCE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALL DECISIONS | COMMITTTEE DECISIONS | ||

| Fermanagh and Omagh | 16 | 29 | +13 |

| Lisburn and Castlereagh | 17 | 27 | +10 |

| Newry, Mourne and Down | 20 | 27 | +7 |

| Antrim and Newtownabbey | 16 | 19 | +3 |

| Causeway Coast and Glens | 15 | 18 | +3 |

| Mid Ulster | 31 | 31 | - |

| Belfast | 1 | 0 | -1 |

| Derry and Strabane | 13 | 10 | -3 |

| Ards and North Down | 9 | 5 | -4 |

| Armagh, Banbridge and Craigavon | 21 | 11 | -10 |

| Mid and East Antrim | 15 | 1 | -14 |

Source: NIAO analysis of Planning Activity Statistics Open Data tables and Department for Infrastructure management information

3.12 Given that planning applications for single rural dwellings are rarely the most complex, we would expect them to account for a lower proportion of committee decisions than of overall decisions. This is not always the case, highlighting a disproportionate use of committee time and focus on these applications.

3.13 In August 2021, the Department issued a ‘Planning Advice Note’ (PAN) on development in the countryside to local councils. The Department told us that the purpose of this PAN was to re-emphasise fundamental aspects of existing strategic planning policy on development in the countryside, as contained in the SPPS; and, clarify certain extant provisions of it. The Department told us that it is clear that the PAN did not add to or change existing planning policy. Councils told us that they were confident the PAN did introduce new policy.

3.14 Following concerns from councils and other stakeholders, the Department advised that “rather than bringing certainty and clarity, as was its intention, the PAN…seems to have created confusion and uncertainty” and this guidance was withdrawn. The Department has advised that it will now take stock of the concerns raised and undertake further engagement and analysis on strategic planning policy on development in the countryside which will include consideration of current and emerging issues, such as climate change legislation and our green recovery from this pandemic.

One in eight decisions made by planning committees in Northern Ireland goes against the recommendation of planning officials

3.15 Departmental guidance for planning committees makes it clear that committees are not always expected to agree with decisions recommended by planning officials. Divergences of opinion between committees and officials are to be expected where planning issues are finely balanced, and a committee may place a different interpretation on, or give a different weight to, particular arguments or planning considerations. However, decisions against officer recommendations must always be supported by clear planning reasons.

3.16 Our review of data covering 2018-19 and 2019-20 shows that just under one in eight applications decided by committee was made contrary to official advice. Whilst the rate varies between councils, in the council with the highest rate, almost one in three decisions taken by the planning committee overturned the recommendation of professional planners (see Figure 7).

| COUNCIL | TOTAL DECISIONS | AGAINST OFFICIALS ADVICE | OVERTURN RATE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermanagh and Omagh | 147 | 45 | 31 |

| Newry, Mourne and Down | 260 | 65 | 25 |

| Causeway Coast and Glens | 183 | 42 | 23 |

| Derry and Strabane | 222 | 37 | 17 |

| Lisburn and Castlereagh | 143 | 15 | 10 |

| Antrim and Newtownabbey | 188 | 17 | 9 |

| Armagh, Banbridge and Craigavon | 101 | 7 | 7 |

| Mid and East Antrim | 78 | 5 | 6 |

| Ards and North Down | 120 | 5 | 4 |

| Belfast | 257 | 6 | 2 |

| Mid Ulster | 445 | 8 | 2 |

Source: NIAO anlaysis of Department for Infrastructure management information

3.17 In the two year period, planning committees overturned 252 decisions recommended by officials. Of these 228, (90 per cent) were cases where the committee granted planning permission against official advice, thus favouring the applicant and unlikely to be challenged.

3.18 Almost 40 per cent of the decisions made against officer advice related to single houses in the countryside. In all of these instances, the officer recommendation to refuse planning permission was overturned and approved by planning committee, contrary to advice.

3.19 In Northern Ireland, if a planning committee refuses a planning application, then the applicant has a right of appeal. In cases where the planning committee grants an application contrary to official advice, there is no third party right of appeal. The variance in overturn rate across councils, the scale of the overturn rate and the fact that 90 per cent of these overturns were approvals which are unlikely to be challenged, raises considerable risks for the system. These include regional planning policy not being adhered to, a risk of irregularity and possible fraudulent activity. We have concerns that this is an area which has limited transparency.

3.20 In making planning decisions it is recognised that planning committees can come to a different decision than its planning officers, however, in doing so they are required to maintain adequate, coherent and intelligible reasons for decisions made. The Department told us that it has previously written through its Chief Planner’s letters to highlight this to councils.

Recommendation

We consider that some of the overturn rates are so high, that they require immediate action both from councils and the Department to ensure that the system is operating fairly and appropriately.

Decision-making processes are not always transparent

3.21 Given the flexibilities that are allowed under current arrangements, and the potential inconsistencies that can arise, it is critical that the process is as transparent as possible. A recent survey by Queen’s University found that the public has low levels of trust in the planning system, and there is a perception that it is not transparent. This survey, for example, noted that only three per cent of citizens felt their views on planning are always or generally considered.

3.22 We found similar concerns in two main areas: in respect of the process by which applications are referred to the committee by elected members, and in respect of those occasions where planning committees make decisions that are contrary to the advice provided by officials.

3.23 A variety of mechanisms is in place to document referrals to planning committees, such as assessment panels or dedicated email addresses. However, not all councils have such mechanisms, they are not available to the public and they do not effectively support greater transparency.

3.24 As part of our fieldwork we reviewed a sample of planning committee minutes. These did not provide a rationale for particular applications being referred to the committee. Some minutes did not distinguish between applications that were being considered under regular Scheme of Delegation operation, and those being considered as a result of a referral.

3.25 The lack of transparency around the overruling of officials’ advice by committees was a key issue identified within the research carried out by Queen’s University. Our review of planning committee minutes showed that reasons for deciding contrary to the recommendation made by officials were not consistently recorded, and minutes often did not contain explicit reference to the applicable planning policy. It was therefore difficult to understand the policy issues underlying the disagreement and committee’s decision. We found no evidence that there was any system in place to monitor such decisions, and ensure that the decisions being made were compliant with overall planning policy.

Recommendation

There is a need for full transparency around decision-making. We recommend that planning committees should ensure that minutes of meetings include details of the applications that are brought to committee as a result of a referral, who brought it to committee and outline the planning reasons why the application has been referred.

We recommend that where a planning committee makes a decision contrary to planning officials’ advice, the official minutes of the meeting should contain details of the planning considerations that have driven the decision.

Planning committees do not regularly assess the outcomes of their previous decisions

3.26 The Department’s guidance for planning committees indicates that they should undertake an annual monitoring exercise to review the impact of planning decisions they have made in the past. It suggests that a committee could inspect a sample of previously determined applications to allow them to reflect on the real-world outcomes. This would enable committees to highlight good and bad decision-making and inform future decisions. We did not find any evidence of a formal review of decisions at any council we spoke to. In our view, this is an important aspect of the quality assurance process which is being overlooked.

Recommendation

Planning committees should ensure that they regularly review a sample of their previously determined applications, to allow them to understand the real-world outcomes, impacts and quality of the completed project. Councils should ensure that they review a range of applications, to ensure that it is not only focused on those applications that tell a good news story about how the system is working. Lessons learned from this process should be shared across all councils.

Training for planning committee members is inconsistent

3.27 Councillors who sit on planning committees have a demanding role. Planning can be a complex policy area, and planning committee members are elected officials who have decision-making powers over planning matters, rather than experts in planning policy and legislation. Consistent and ongoing training on planning matters is therefore an essential feature of a well-functioning planning committee. Whilst the exact level of training necessary can vary, a report by the Royal Town Planners Institute (RTPI) in Wales suggested a minimum level of continuing professional development for all committee members of 10 hours per year.

3.28 From September 2014 to January 2015, the then Department of the Environment held capacity building and training events for elected representatives in preparation for the transfer of planning functions to the councils. This included a full day session on propriety, ethics and outcomes. Whilst there was a focus on providing core training when planning functions transferred in 2015, subsequent training requirements for planning committee members have varied from council to council, and appear to have been completed on a more ad hoc basis. Whilst most councils have mandatory induction training and training for committee Chairs, ongoing training is not always compulsory for elected members. The Department has liaised with the Northern Ireland Local Government Association since 2015 to assist in their development of training programmes for elected members.

3.29 In our view, there is the potential to centralise training for committee members, which would also reduce the administrative burden on planning services which are already under resourced and struggling with workload. This would also ensure that those making decisions have all had the same training, making the process fairer for people submitting planning applications.

Recommendation

Councils should consider the introduction of compulsory training for members of planning committees, including procedures where training requirements have not been met.

The Department should ensure that training provided to planning committee members is consistent across all councils and sufficient to allow elected members to fulfil their duties.

Part Four: Departmental oversight

4.1 The Department has a number of responsibilities in relation to planning. These include:

- oversight of the planning system in Northern Ireland;

- preparing planning policy and legislation;

- monitoring and reporting on the performance of councils’ delivery of planning functions; and

- making planning decisions in respect of a small number of Regionally Significant and called-in applications.

Regionally Significant applications are the most complex applications and often take years to decide on

4.2 Regionally Significant development applications are those considered to have the potential to make a critical contribution to the economic and social success of Northern Ireland as a whole, or a substantial part of the region. They may have significant effects beyond Northern Ireland, or involve a substantial departure from a Local Development Plan.

4.3 These applications are submitted to, and processed by, the Department. There are typically very few of these applications decided in a given year, with only seven processed between 2016-17 and 2020-21. Whilst there is no statutory processing time target, there is a Departmental target to process regionally significant planning applications from date valid to a Ministerial recommendation or withdrawal within an average of 30 weeks. Only one of the seven applications processed between 2016-17 and 2020-21 was decided within 30 weeks, with four taking more than three years to process. Of the three Regionally Significant applications pending at 31 March 2021, two had been in the system for more than three years. Given the economic significance of these projects, any delay is likely to have a negative impact on potential investment.

4.4 The Department told us that the absence of the Assembly from January 2017 to January 2020 impacted on the its ability to take planning decisions and in particular, the 2018 Court ruling in Buick prevented planning decisions being made by the Department until legislation was enacted which allowed senior civil servants to take certain decisions. With the return of the Executive, the ruling has continued to have impacts on planning. I n addition, whilst performance can be improved, poor quality planning applications entering the system and increased requirements under environmental regulations have also impacted the timeliness for processing major and regionally significant applications.

4.5 The Department is also responsible for determining a number of Major and Local applications each year. These also typically take a long time to process. Of the 28 Major applications processed by the Department between 2016-17 and 2020-21 only three were processed within 30 weeks, and 19 took more than three years. Of the twenty live Major applications being determined at 31 March 2021, 18 were more than one year old with nine of those being more than three years old.

4.6 Of the 29 Local applications processed by the Department between 2016-17 and 2020-21, 17 took longer than 30 weeks – twice the 15 week target – and 14 of those took more than one year to process. All of the ten Local applications being processed by the Department at 31 March 2021 were more than one year old.

The Department is currently undertaking a review of the implementation of the Planning Act

4.7 The Planning Act contains a provision that requires the Department to review and report on the implementation of the Act. The review will:

- consider the objectives intended to be achieved by the Planning Act;

- assess the extent to which those objectives have been achieved; and

- assess whether it is appropriate to retain, amend or repeal any of the provisions of the Planning Act or subordinate legislation made under the 2011 Act, in order to achieve those objectives.

4.8 The review will also provide an opportunity to consider any improvements or ‘fixes’ which may be required to the way in which the Planning Act was commenced and implemented in subordinate legislation.

4.9 The Department has stated that the review is not envisaged as a fundamental root and branch review of the overall two-tier planning system or the principles behind the provisions as, in its view, it is still relatively early days in the delivery of the new system. In our view, this is an important opportunity to make improvements across the whole system.

The Department should provide leadership for the planning system

4.10 Our review has identified significant silo working in the planning system. We have seen a number of instances where individual bodies – either councils, the Department or consultees – have prioritised their own role, budgets or resources rather than the successful delivery of the planning service. The Department told us that these and other diseconomies of scale caused by decentralising the planning system were recognised at the time of transfer but were considered to be offset by the advantages of bringing local planning functions closer to local politicians and communities.

4.11 Each organisation is accountable for its own performance, and whilst the Department monitors the performance of individual organisations against statutory targets, there is little accountability for the overall performance of the planning system. Whilst individual organisations within the system stressed the challenges they faced; ultimately the frustration from service users was the poor performance of the system, not issues in individual bodies.

4.12 In our view, the ‘planning system’ in Northern Ireland is not currently operating as a single, joined-up system. Rather, there is a series of organisations that do not interact well, and therefore often aren’t delivering an effective service. This has the potential to create economic damage to Northern Ireland. Ultimately, as it currently operates, the system isn’t delivering for customers, communities or the environment.

4.13 In our view, this silo mentality presents both a cultural and a practical challenge. The focus for all of those involved in the system must be the successful delivery of planning functions in Northern Ireland, not the impact on their own organisations. This will require significant leadership of the system – in our view the Department is well placed to provide this leadership. However, it is crucial that all statutory bodies involved in the planning system play their part in this and fully commit to a shared and collaborative approach going forward.

4.14 The Department has made initial steps, but more will have to be done. Leadership of the system must encompass a number of areas:

- the long term sustainability of the system;

- ensuring those involved have access to the necessary skills and experience;

- enhancing transparency and ethical standards;

- encouraging positive performance across the system; and

- the promotion of the value and importance of planning across government as a whole.

4.15 The Department told us that it has committed significant energy and resources to leading and fostering a collaborative and shared approach to improving the planning system here. Since March 2015 the Department has led and interacted with councils and other stakeholders across a wide range of meetings, such as the Strategic Planning Group, the Planning Forum, the Environmental Working Group, the Continuous Planning Improvement working group, and the Development Management Working group. However, the Department told us that it is committed to ensuring transparency and ethical standards, but that lead responsibility for these lies with both the councils and the Department for Communities, through the Code of Conduct for Councillors.

The planning system is increasingly financially unsustainable

4.16 When planning responsibilities transferred to councils, it was on the basis that the delivery of services should be cost neutral to local ratepayers at the point of transfer. However, as was the case in the years preceding transfer, the income generated from planning does not cover the full cost of service delivery. This has meant that historically there has been a need to supplement income with other public funding to deliver planning services. Our review of financial information provided by councils has shown that the overall gap between the income generated from planning activities by councils and the cost of those activities increased significantly between 2015-16 and 2019-20 (see Figure 8).

4.17 It was intended that the gap between income and expenditure at individual council level would be met by a grant paid by central government to councils. This grant was intended to provide funding for a number of service areas, of which planning is one. Whilst there have been requests from councils for the Department for Communities to review the level of funding, no review has been undertaken.

4.18 In our view, the Department appears to have given little consideration to the long-term sustainability of the planning system, despite the increasing gap between income and expenditure. The Department told us that it is responsible for setting planning fees (once agreed by the Minister), but not for the long-term funding of councils.

Planning fees have not contributed to the financial sustainability of the system

4.19 Planning decisions increasingly are more complex and require more interaction with those who have specialist knowledge or skills. This requires more work for many applications. In contrast to these increasing demands, planning fees, the main source of income for the planning system, have not been adjusted year on year to keep pace with inflation and the increasing complexity being asked of decision-makers. The result is that less income is being generated in real terms year on year, despite increasing amounts of work being undertaken by planning teams.

4.20 The fees that councils charge for planning applications were initially set in 2015, with individual rates set for different types of development application. Since then, these have been increased on one occasion. Changes to planning fees require legislation to be brought through the Assembly. The absence of a functioning Assembly and Minister placed constraints on the Department’s ability to bring forward fee increases. However the Department told us that it was able to raise fees once (by around 2 per cent, in line with inflation in 2019) following the enactment of the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation and Exercise of Functions) Act 2018, which allowed the Department to take certain decisions normally reserved to the Minister. The Department told us that further increases have been placed on hold due to the pandemic. Fees are currently around 12 per cent lower than they would be had the prices set in 2015-16 been increased in line with inflation each year. This is unsustainable in the longer term.

4.21 During our discussions with stakeholders, we were told on a number of occasions that small increases in fees were unlikely to have a significant impact on the number of development proposals being made. Typically, the planning fee cost is a very small element of the total cost of a development, and a small increase is not likely to be material to the overall financial appraisal underlying a proposal. However, developers we spoke to asserted that if fees were to increase, they would expect service levels to improve.

4.22 A number of councils also told us that due to the increasing complexity of cases, many fees no longer reflect the costs incurred. Whilst determining the true costs of providing planning services will be challenging, fees that more accurately reflect the true cost will ultimately ensure a more sustainable system. The Department recognises that this is ultimately a policy decision for the Minister.

Recommendation

We recommend that the Department and councils work in partnership to ensure that the planning system is financially sustainable in the longer term.

The way performance is monitored and measured does not provide a comprehensive overview of performance

4.23 The Department has taken a number of steps in oversight of the performance of the system. Its ability to perform this function is dependent upon adequate performance measurement and reporting arrangements. Ensuring that these are in place is a key tool in maintaining accountability for performance within the system – between the various organisations spanning local and central government involved in delivering the system – and wider accountability to the Assembly and public for overall performance of the system as whole.

4.24 There have been efforts to improve the quality of performance information that is available about the planning system. Since 2018-19, the Department has supplemented its reporting on performance against the three time-based targets with a set of measures reporting various trends in council decision-making processes – the Planning Monitoring Framework. This represented an effort by the Department and councils to develop a more comprehensive approach to reporting on planning system performance than that provided by measuring performance against the statutory time-based targets. However, not all proposed indicators were agreed by councils at the time.

4.25 The Department has also been gathering, reporting and more recently publishing in more detail the performance of statutory consultees. This is a welcome development, given the critical role that statutory consultees play within the process and the performance issues within this part of the planning system.

4.26 However, in our view more work is required to establish an effective system of performance measurement and reporting which goes beyond volume of activities, proportions and timeliness. Oversight requires measures that are accepted by all stakeholders as providing meaningful information about performance and identifying issues that need to be addressed. Being able to compare performance between councils and consultees, over time, and against established standards or targets, is what makes information meaningful and can drive accountability and action.

4.27 One of the key deficiencies is the lack of information about the input cost of the various activities being undertaken and reported on. Such information is critical for understanding the full cost of the planning system, measuring the efficiency of the system, identifying areas where there may be inefficiency, and for developing an appreciation of the financial pressures that planning authorities face and the impact these have on performance.

Performance management information has not been used to drive improvement

4.28 The Department told us that since 2019 it has been working with statutory consultees and local government through the Planning Forum to improve performance of the planning system. This work is particularly focused on improving the performance of major planning applications. Prior to that the Department established and led the Continuous Improvement Working Group. We have not seen any evidence of self-review within councils or learning from experience, for example, reviewing the results of past decisions made in terms of built development, job creation or contribution to the local economy.

4.29 In the short term, it is important that the Department and other organisations put appropriate measurement and reporting systems in place. Over the medium and longer term, they must consider how performance measurement can provide the basis for improving performance and delivering quality outcomes.

Performance monitoring is currently more concerned with the speed and number of applications processed, than the quality of development delivered

4.30 Since 2016, the Executive has been committed to delivering an outcomes-based Programme for Government across the public sector, placing wellbeing at the core of public policy and decision-making. Organisations are required to ask themselves three key questions: “How much did we do?”, “How well did we do it?”, and “Is anyone better off?”

4.31 Despite the Executive’s commitment to outcomes-based accountability, performance measurement within the planning system is predominantly concerned with the speed and quantity of decisions, rather than quality of outcomes. Whilst the Department sought to introduce more qualitative indicators through the Planning Monitoring Framework, there is no publically available information demonstrating how planning decisions have translated into built development, improved or enhanced the built or natural environment, benefitted communities or contributed to the economy.

4.32 The lack of outcomes-based accountability measures within the planning system has a number of potential consequences:

- Broader, long-term impacts are not routinely captured and demonstrated, and so the value of the planning system is underestimated.

- The cumulative effect of planning on communities, towns and regions is not being measured.