List of Abbreviations

ACE: Assessment, Case Management and Evaluation System

BHSCT: Belfast Health and Social Care Trust

CJB: Criminal Justice Board

CJINI: Criminal Justice Inspection Northern Ireland

ECO: Enhanced Combination Order

HMICFRS: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services

HSCB: Health and Social Care Board

NIAS: Northern Ireland Ambulance Service

NICTS: Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service

NIPS: Northern Ireland Prison Service

OLCJ: Office of the Lord Chief Justice

PBNI: Probation Board for Northern Ireland

PFG: Programme for Government

PHA: Public Health Agency

PPS: Public Prosecution Service

PSNI: Police Service of Northern Ireland

SEHSCT: South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust

SPAR: Supporting Prisoners at Risk

TEO: The Executive Office

Key Facts

POLICING

98,000 - The numbers of crimes reported to PSNI in 2017-18

22,000 - The number of suspects arrested by PSNI during the course of their investigations in 2017-18

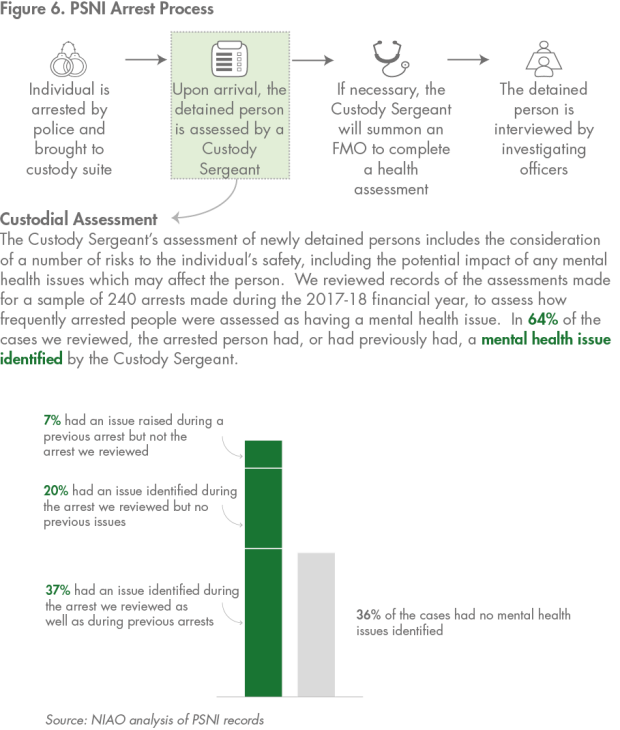

64% - The proportion of arrested suspects currently or previously identified as having mental health issues in a sample of arrests made in 2017-18

PROSECUTION AND CONVICTION

25,000 - The number of defendants successfully prosecuted in court in 2017

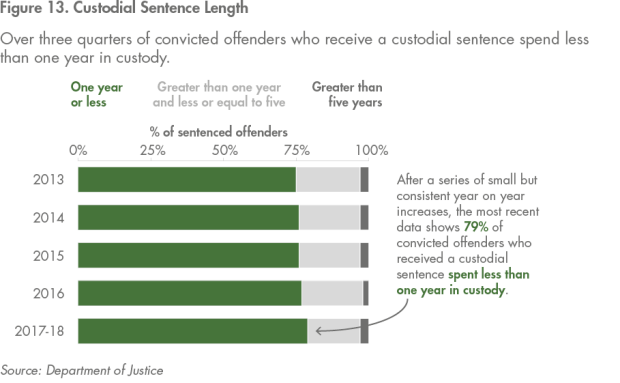

2,900 - The number of convicted defendants who received a custodial sentence in 2017

2,800 - The number of convicted defendants who received a community supervision sentence in 2017

CUSTODIAL SENTENCES

79% - The proportion of prisoners who served a period of less than one year in custody as part of their sentence in 2017-18

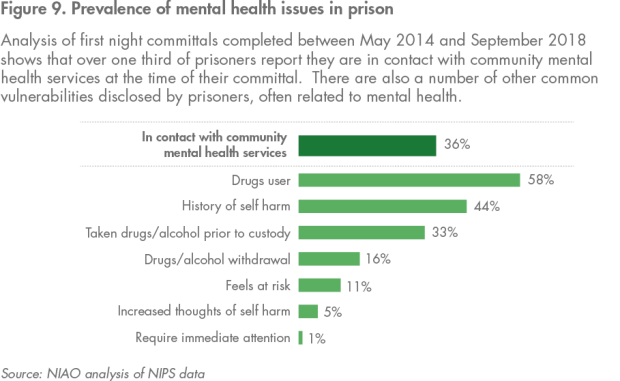

36% - The proportion of prisoners who reported they were currently in contact with community mental health services at the time of their committal to prison between May 2014 and September 2018

9% - The proportion of prisoners who reported that they were not registered with a GP in the community at the time of their committal in a 2017 prisoner survey

COMMUNITY SENTENCES

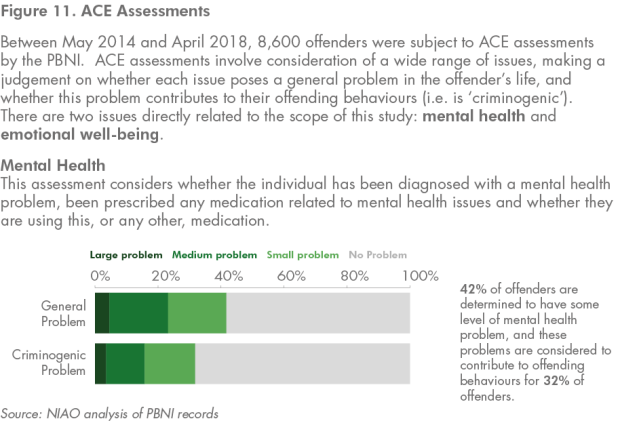

42% - The proportion of offenders assessed by PBNI (using ACE tool) determined to have a mental health issue between May 2014 and April 2018.

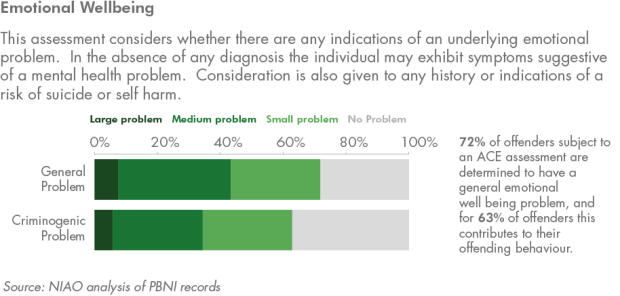

72% - The proportion of offenders assessed by PBNI (using ACE tool) determined to have an emotional well-being issuebetween May 2014 and April 2018

Executive Summary

1. The justice system aims to protect the public, bring offenders to justice, support victims and support the rehabilitation of offenders to reduce the overall level of offending. Around 100,000 crimes are reported to the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) each year. Approximately 24,000 people are convicted in court of committing a criminal offence each year. Typically, around 3,000 offenders receive a custodial sentence, served in one of Northern Ireland’s prisons, run by the Northern Ireland Prison Service (NIPS). The Probation Board of Northern Ireland supervises approximately 3,500 individuals in the community, and works with 1,000 of those held in prison each year.

2. Many of these individuals are repeat offenders, trapped in a cycle of reoffending without making effective progress towards rehabilitation. The most recent analysis published by the Department shows that 41 per cent of offenders who complete a custodial sentence reoffend within one year of release; 35 per cent of those sentenced to community supervision also reoffend.

3. A common characteristic of those who are convicted is the high prevalence of a number of social and health issues. People who repeatedly encounter the justice system frequently live chaotic lives. Whilst there is a lack of up-to-date comprehensive and authoritative evidence, most research concludes there are higher rates of a range of social and health issues amongst those who encounter the justice system than in the general population. Examples of such issues include mental health, alcohol and substance abuse, homelessness, a lack of educational attainment and employment opportunities, and psychological damage caused by previous traumatic experiences.

4. Achieving the objectives of the justice system is complicated by the more general challenge of providing mental health services to the public. Many of the people with complex health and social needs who come into the justice system have not been in contact with key services in the community. There are a number of structural issues affecting the provision of mental health services across Northern Ireland. Expenditure has not kept pace with demand and individuals can struggle to access the care they need. Where such individuals offend, the justice system can become the service of last resort.

5. In such cases, the responsibility of the justice system is to work collaboratively with healthcare providers to ensure that there are effective arrangements for assessing these individuals, and for facilitating the provision of health services whilst the person is in contact with the justice system. The justice system recognises that it has not been able to meet this responsibility consistently in a way that supports its wider rehabilitative objectives. The system has found it difficult to evolve in line with the increasing prevalence of mental health issues amongst those it is required to prosecute and rehabilitate. Positive outcomes of contact with the justice system include cases where the system has been able to support the individual’s connection or re-connection to health services.

6. Operational challenges are evident at all of the key stages of the justice process. It has been challenging for PSNI to engage effective health assessment and facilitate access to wider healthcare provision for individuals who are arrested. The PSNI has also been confronted by a drastic increase in the number of non-criminal incident reports it receives. These calls typically result in officers attending incidents where no crime has been committed, but an individual is experiencing a mental health or emotional crisis.

7. For those prosecuted and convicted, the current sentencing framework is generally considered to be ineffective in supporting rehabilitation. In particular, the high proportion of short custodial sentences is widely recognised as being ineffective and inefficient. The Northern Ireland Prison Service and its key partner, the South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust (SEHSCT), have found it challenging to ensure that the prison system in Northern Ireland is a safe and healthy environment for those detained.

8. Finally, there are barriers that can hinder those departing the justice system at the completion of their sentence from accessing the health and social services that they need to support their continued rehabilitation and resettlement into the community. The disparate nature of services, for example the different working practices of the different health trusts in Northern Ireland, is a key structural factor that complicates the work of justice organisations.

9. Historically, these issues have been compounded by the disconnected nature of the wider public service network. The needs of at risk offenders can cross a number of different organisational and departmental boundaries, and an effective response depends on different public service organisations working together coherently. The justice organisations we spoke to emphasised that current relationships with health organisations are positive and contributing to progress, but structural barriers to more effective working practices remain.

10. The justice system has recognised these issues and is implementing an ambitious programme of reforms, in collaboration with partners from the health system. The reforms being developed touch on all areas of the justice system, from the reporting of incidents to the completion of a sentence. The development of these initiatives has placed a heavy emphasis on collaboration and improving the quality of organisational relationships. Reassuringly, health and justice organisations have in recent years demonstrated an improvement in their ability to work together effectively.

11. Despite the progress made so far, there remain a number of key structural challenges. There is currently no high level leadership group directing and overseeing implementation of the reform programme as a whole. The Criminal Justice Board has significant potential to help overcome both general and specific barriers to the development of a system-wide response in respect of solely justice issues. In our view, there is a need for a similar group to take the lead in delivering a programme of reforms to improve the justice process for offenders with mental health issues.

12. There is a lack of precision and clarity around what success for the reform programme looks like, at the level of the justice system as a whole and in relation to outcomes for offenders which cross public sector departmental boundaries. At a strategic level, a framework of shared definitions of key terms and transparent mapping of outcomes for offenders, can support the better management of reform and better communication of the progress being made.

13. Good quality data is an essential ingredient for success. The justice system and its partners do not collect enough good quality data about mental health and other key vulnerabilities amongst offenders. Information currently recorded is too often in a format that does not support effective analysis and management decision-making. The establishment of consistent definitions will support better quality measurement of the issues across individual organisational boundaries, and the progress individuals make once they have exited the system.

Part One: Introduction

Mental health is a significant public health issue in Northern Ireland

1.1 Northern Ireland has a relatively high level of mental health issues amongst the population. In 2011, the Department of Health identified mental health as one of the four most significant causes of ill health and disability in Northern Ireland. The Chief Medical Officer has consistently reported that one in five people in Northern Ireland will have a mental health problem during their life. The general prevalence of mental health problems is considered to be around 25 per cent higher than in England and Wales, due to a range of economic and social factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Issues which contribute to high levels of mental health issues in Northern Ireland

- Socio-economic deprivation in Northern Ireland is significantly higher than in Great Britain.

- The rurality of our population distribution is contributing to higher costs for mental health services.

- The health of our population is generally poorer compared to Great Britain.

- The link between deprivation and health and social care needs is particularly strong in mental ill-health.

- The aftermath of the Troubles is still being experienced, for example, in terms of mental health problems and needs, and this is likely to continue for many years.

- Investment levels in mental health services have not kept pace with other areas of the UK and there are significant gaps in service provision.

- As a result of a general failure to replace or redevelop the ageing estate and to address a growing backlog across Northern Ireland, a significant capital investment in mental health services is required.

1.2 Whilst mental health is a high profile issue, there can often be a lack of precision in public discourse. Commonly used language, including the term mental health itself, can mean different things to different people. Justice and health organisations told us that they consider many common public assertions about mental health to be inaccurate and not supported by evidence.

1.3 The challenge of accurately defining mental health in a way that is aligned to operational reality is evident in the legislative environment in Northern Ireland. Currently, the assessment, treatment and rights of individuals with mental health issues are covered by the Mental Health (Northern Ireland) Order 1986. The definition of mental disorder within the Order excludes people whose disorder is a result of Personality Disorder only. This is significant for the justice system, as it is widely acknowledged the prevalence of Personality Disorder is relatively high amongst those in contact with the justice system compared to the general population, and is a challenging issue for justice organisations to manage.

1.4 Our understanding of the issue has been based upon the World Health Organisation definition of mental health as “a state of wellbeing in which every individual reaches his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community”. Under this broad interpretation, suffering from mental health issues is not restricted to cases where a person has a diagnosed clinical condition. Someone who has a diagnosed disease or disorder may still enjoy a high level of wellbeing and therefore not be in a constant state of poor mental health. Similarly, a person may have mental health issues despite not having a diagnosed disease or disorder. Within the operational context of the justice system, this broadness makes defining the issue challenging.

Achieving the objectives of the justice system is complicated by the more general challenge of providing mental health services to the public

1.5 The objectives of the justice system are to protect the public, to bring offenders to justice, to support victims, and to support the rehabilitation of offenders to help reduce the overall level of re-offending. Meeting these objectives has become increasingly challenging in recent years in the general context of significant reductions in the resources available to justice organisations (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Criminal justice expenditure

|

Organisation |

Outturn 2011-12 (£m) |

Outturn 2017-18 (£m) |

Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Department of Justice |

55 |

32 |

-42% |

|

PSNI |

890 |

691 |

-22% |

|

NIPS |

152 |

95 |

-38% |

|

PBNI |

21 |

18 |

-14% |

|

TOTAL |

1,118 |

836 |

-25% |

Source: Department of Justice

1.6 The nature of justice organisations’ engagement with the population they serve has also been complicated. On one hand the overall volume of cases proceeding through the system has decreased over recent years, which suggests a decrease in the overall volume of demand on these organisations (Figure 3). However, justice organisations argue that decreasing volumes mask an increasing complexity of needs among those they deal with.

Figure 3. Criminal justice organisations’ case volume trends

|

Stage |

2012-13 |

2017-18 |

Change |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Recorded Crimes |

99,000 |

98,000 |

-1% |

|

Police arrests |

25,000 |

22,000 |

-12% |

|

Court prosecutions* |

38,000 |

28,000 |

-26% |

|

Court convictions* |

32,000 |

25,000 |

-22% |

|

Custodial sentences* |

3,700 |

2,900 |

-22% |

|

Average Prison Population |

1,800 |

1,400 |

-22% |

|

Community sentences* |

3,400 |

2,800 |

-18% |

|

PBNI Caseload |

4,500 |

4,100 |

-9% |

* These figures relate to the 2012 and 2017 calendar years. Figures for numbers of custodial and community sentences imposed relate to principal offence at disposal.

Source: Department of Justice, PSNI, PBNI, and NIPS

1.7 Many offenders live chaotic lives. A range of often co-existing social, economic and health problems can impair the ability of people to lead a healthy productive life and can contribute to offending behaviours. Common problems include mental health issues, alcohol and substance abuse, homelessness, a lack of educational attainment and employment opportunities, and psychological damage caused by previous traumatic experiences. Trauma can often stem from childhood experiences, which can affect a child’s long-term physical and mental development.

1.8 The health and social care system in Northern Ireland has struggled to respond to the high levels of mental health issues. The Bamford Review, undertaken during the early 2000s, was intended to facilitate the development of a long-term plan for improved provision of mental health services in Northern Ireland. However, implementing its recommendations has been problematic, with financing both existing mental health services and the suggested reforms a significant challenge.

1.9 In 2016, the Commission on Adult Acute Psychiatric Care highlighted a number of key strategic issues that continue to impact on the provision of mental healthcare in Northern Ireland more than a decade after the Bamford Review (Figure 4). Expenditure on mental health services had not increased in line with expenditure on other health areas, and financial pressures across the health system meant that resources originally allocated to mental healthcare budgets were often used to cover shortfalls in physical healthcare budgets.

Figure 4: System-wide problems in provision of adult mental health services

- Inadequate availability of acute inpatient care, specialist inpatient care and community-based alternatives to acute and/or specialist inpatient admissions when needed.

- Many patients remain in inpatient beds for longer than is necessary, in significant part because of inadequate residential provisions out of hospital.

- Variable quality of care in inpatient units, reflecting the environment, the interventions available and the number and skills of health and care workers.

- Variation in terms of access to evidence-based therapies across the entire acute care pathway.

- Poor provision of psychological and other specialist services.

- A lack of clarity as to the quality outcomes expected and how these should be reported in a transparent way.

- Variable involvement of patients and their carers in both care received and in the organisation of services.

- A fragmented and relatively weak approach to the commissioning of services.

Source: Building on Progress: Achieving parity for mental health in Northern Ireland, Commission on Acute Adult Psychiatric Care, June 2016

1.10 These health and social issues may present a risk to the safety of an individual whilst they are in contact with the justice system, for example whilst being held in prison or police custody. They can also frequently present a barrier to effective rehabilitation, intended to support the offender resettling into the community at the end of their contact with the justice system and not reoffending.

1.11 The key responsibility of the justice system in respect of such offenders is to work collaboratively with healthcare providers to ensure that there are effective arrangements in place for the provision of health services whilst the person is within the ambit of the justice system. Justice organisations must work with public health organisations to establish a means of identifying health-related issues and vulnerabilities, systems for monitoring the condition of people identified as having an underlying issue, and strategies for helping these people access treatment that can help them.

1.12 Collaborative arrangements have existed in various parts of the system for some time. The PSNI has a list of contracted GPs used on a call-off basis to provide medical assessments of individuals held in police custody. At the time of writing the PSNI, in partnership with the Public Health Agency, has developed and is piloting a move towards the introduction of nursing staff to provide care for individuals held in police custody. Medical services for those held in prison is primarily provided by the South Eastern Health & Social Care Trust (SEHSCT).

1.13 However, the framework of collaborative working established for the last decade has not kept pace with the evolving profile and needs of the people who encounter the justice system. While this partly relates to issues affecting the general provision of mental health services in the community, the justice system has failed to ensure that the way it and its collaborative relationships operate evolved to meet the changing demands it faces.

The justice system has prioritised developing a better response to mental health issues

1.14 In June 2018, the Executive Office (TEO) launched an Outcomes Delivery Plan setting out the actions that departments intend to take to meet the stated objective of the previous Executive’s draft Programme for Government: “Improving wellbeing for all – by tackling disadvantage and driving economic growth”. The key outcome relevant to mental health in the criminal justice system is Outcome 7: ‘we have a safe community where we respect the law, and each other’. This includes commitments to:

- driving forward reforms and initiatives to prevent offending and reoffending – focusing especially on early intervention, and providing greater opportunities for young people; and

- creating the social conditions that reduce the risk of criminal behaviour, intervening early, engaging with young people and getting the right help at important times in their lives.

1.15 The Delivery Plan notes the particular prevalence of mental health issues amongst offenders as being a key issue related to the achievement of Outcome 7. The system accepts that the way it currently operates is not effective in providing a service to people with mental health issues. Current practices often mean that interaction with the justice system exacerbates the problems some people face and can contribute to an individual’s reoffending.

1.16 This is both ineffective in terms of outcomes for offenders and an inefficient use of public funds. To have a substantial number of people who pass repeatedly through the same expensive process (police investigation, detention, prosecution and custodial sentence) imposes an ongoing pressure on the public purse. It is widely accepted that successful intervention and rehabilitation, which breaks the cycle of offending and punishment, is a far more financially efficient and effective response to criminal offending overall.

1.17 To remedy this, justice organisations intend to develop an approach for offenders with mental health issues within a broader framework of initiatives targeting offenders with complex and difficult needs. The objectives of the reform programme are two-fold. On one level there is a desire to improve how the justice organisations interact with people with mental health issues. The primary purpose of this interaction is to meet the statutory objectives of justice organisations, but it also provides an opportunity to help wider public service networks engage with people who could benefit from those services. For example, contact with the justice system presents an opportunity to:

- allow professional health practitioners to diagnose previously undiagnosed mental illnesses and conditions;

- provide a regulated and orderly environment within custody, removing individuals from detrimental influences in the community;

- provide the individual with access to health, alcohol and drugs services; and

- incentivise people to engage with key services.

1.18 More fundamentally, and more significantly in the long-term, there is an expectation that, by improving how interfaces between health and social services and the justice system work, interventions can take place earlier in an individual’s life, before they have become significantly involved with the justice system. Such early interventions are at the forefront of the current Programme for Government (PfG) and included in our forward work programme, which includes planned reviews on social deprivation and its links to educational achievement; and the provision of addiction services in Northern Ireland.

Scope and structure

1.19 This report provides a high-level overview of how the criminal justice system encounters mental health issues and the key problems that can arise. It considers the main issues that challenge the effectiveness of the system’s engagement with people with mental health issues at key stages: the reporting of incidents to the PSNI; the arrest and detention of subjects in police custody; the use of remand for individuals prosecuted at court; the sentencing of convicted offenders; and the services available to support convicted offenders.

1.20 There are certain areas outside this scope that are very relevant to the outcomes the system can achieve. In particular, the Youth Justice Agency has an important role in meeting the mental health needs of offenders who may later move into the adult justice system. We reported on this aspect of the system in 2017.

1.21 A number of reform initiatives designed to address these issues has already begun, with more in development. We have considered the governance framework around these, and have made key strategic recommendations that will enhance the system’s ability to achieve the positive outcomes to which it aspires.

1.22 The report is structured as follows:

- Part Two maps out the pathway through which offenders progress when they encounter the justice system. It also provides an indication of the extent of mental health issues amongst offenders at key stages.

- Part Three highlights the key issues which affect the quality of outcomes achieved for people with mental health issues.

- Part Four considers the ongoing reforms programme, and the governance framework that is required to ensure this achieves its full potential.

Part Two: The criminal justice pathway and the prevalence of mental helath issues

2.1 This part of the report provides an overview of how the justice process works, using information from key justice organisations to provide an indication of the general prevalence of mental health issues amongst those who progress through the system.

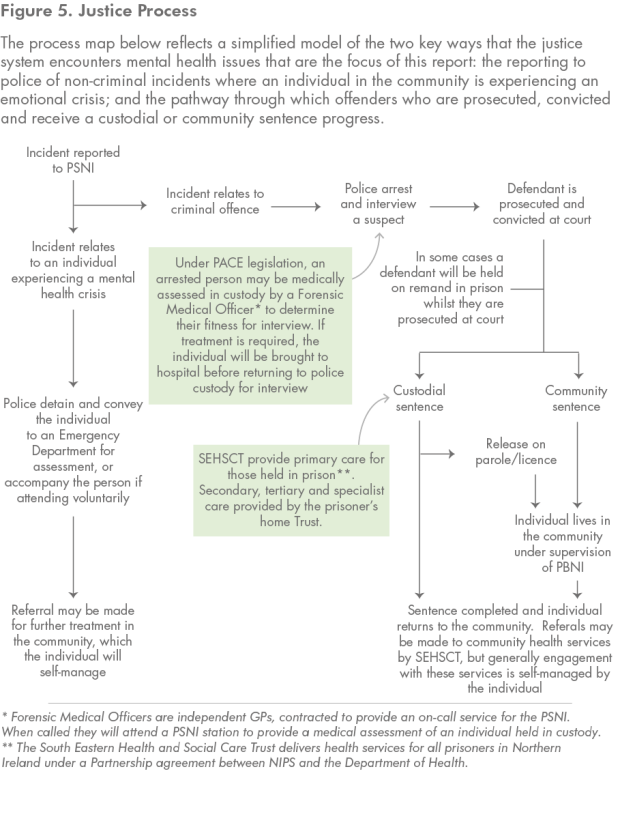

2.2 The entire justice system is a complex network of different organisations and processes. There are a multitude of possible pathways and outcomes for those who encounter it. We have provided a simplified overview of how the process works (Figure 5). The map also highlights the arrangements that have been in place in recent years to provide medical care at key junctures of the process for those who require assessment, referral or treatment.

The police regularly encounter individuals with mental health issues

2.3 The PSNI is, by some margin, the largest justice organisation and the main interface between the justice system and the community. In this ‘front-end’ role officers interact regularly with people with mental health issues and with health services. This contact occurs in two main ways.

2.4 The first is when police respond to an incident where an individual is exhibiting behaviour suggestive of mental health issues, to the extent that they are perceived to be a risk to themselves or others. Such events frequently do not involve a criminal offence. The expectation of those reporting the incident is that police will be able to manage and resolve the situation. Typically, the outcome is that officers either detain the person and bring them for appropriate medical attention or convince them to seek attention voluntarily.

2.5 The recorded number of such incidents has steadily increased from 9,000 in 2013 to over 20,000 per year. These calls can impose significant operational demands upon the PSNI, often taking up to half an hour to resolve, imposing greater demands on the call management system. Responding officers can often be involved for between 18 and 30 hours, reducing the PSNI’s operational capacity for that duration.

2.6 The second main way that officers encounter people with mental health issues is when they arrest and detain a subject following a criminal offence. Each year, officers arrest over 20,000 subjects for interview. When arrested, each individual undergoes an assessment process that considers a range of issues that may pose a threat to their safety in police custody, including mental health (Figure 6). Two-thirds of people arrested by the PSNI are identified as having a mental health or potential mental health issue. When the PSNI interviews someone identified as mentally vulnerable, that person is provided with an Appropriate Adult. The Appropriate Adult provides support to the individual whilst they are in custody and being interviewed, ensuring that the detained person understands what is happening to them and their rights

Most offenders are dealt with in court but only a portion receive a custodial or community sentence

2.7 Once the PSNI has gathered sufficient evidence, there are two ways to submit a case to the PPS – by reporting the case without charging the suspect or by charging the suspect, followed by a report to PPS. Following receipt of a file, prosecutions are initiated or continued by the PPS only where it is satisfied that the Test for Prosecution is met. This is a two stage test (Evidential Test and Public Interest Test) and each stage must be considered in turn and passed before a decision to prosecute can be taken. The most serious offences are prosecuted in the Crown Court, whilst the majority of less serious matters are heard in the Magistrates’ Court. There are other options available allowing prosecutors to deal with offenders other than through prosecution, including cautions, informed warnings and youth conferencing.

2.8 The PPS Code for Prosecutors provides guidance relating to mental health considerations in respect of offenders. This outlines the need to balance a suspect’s mental or physical ill-health with the need to safeguard the public or those providing services on behalf of the public. The PPS Code recognises that mental health issues are of considerable, and sometimes crucial, importance. They can feature in the context of the decision as to prosecution, and also when the court is determining criminal responsibility or considering the appropriate sentence. The PPS will normally become aware of a mental health issue relating to an accused person from information provided to it by the PSNI or by the defence. Where a mental health issue is identified and raised with the PPS, prompt consideration must be given as to whether it is necessary to obtain relevant expert evidence. Issues relating to mental health will then be considered and disclosed as required.

2.9 For this part of the process - the prosecutorial decision-making and the entry of cases to the courts - it has not been possible to summarise the number of people with mental health issues. The management information systems used by the PPS and the Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service (NICTS) do not record the prevalence of mental health issues in any useful way. The Causeway system is used to transmit information between justice organisations, but does not currently do so in a way that allows prosecuted individuals with mental health issues to be identified automatically.

Mental health issues and general vulnerability are common amongst convicted offenders

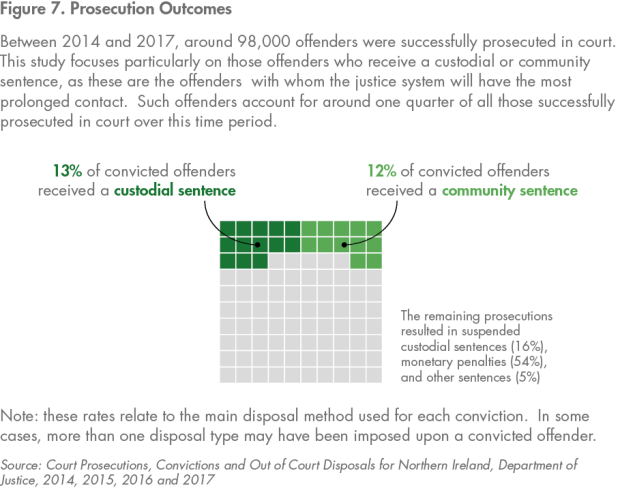

2.10 When a defendant is convicted, there are a number of potential sentences that can be imposed. The most significant sentences in terms of impact upon an individual’s life are custodial or community sentences. This study focuses on the experiences of the subset of offenders who receive a custodial or community sentence (Figure 7). Such offenders willremain in contact with the justice system for a determined period of time, offering the system an opportunity to engage with them and work towards supporting their rehabilitation.

2.11 Custodial sentences are served in one of Northern Ireland’s four prisons, dependent upon the offender’s profile (Figure 8). Offenders who receive a community sentence remain living within the general community, but are placed under the supervision of the Probation Board for Northern Ireland (PBNI) during their sentence. Some offenders may receive a sentence that combines custody and a community element.

Figure 8. Prison estate

|

Establishment |

Description |

2017-18 Average Population |

|---|---|---|

|

Maghaberry |

Maghaberry is a modern high security prison housing both sentenced and remand adult male prisoners |

860 |

|

Magilligan |

Magilligan is a low security prison holding male prisoners who meet the relevant security classification and generally have less than six years to serve |

430 |

|

Hydebank Wood College |

Hydebank Wood houses young offenders between the ages of 18 and 24, and places a focus on education, learning and employment training |

100 |

|

Ash House |

Ash House is a block within the Hydebank Wood complex, and accommodates female remand and sentenced prisoners |

60 |

Source: The Northern Ireland Prison Population 2017-18, Department of Justice

Offenders serving custodial sentences

2.12 Individuals sent to prison, whether under remand or sentence, are initially subject to committal by Prison Service staff. The new prisoner is asked a series of scripted questions designed to identify key risks that prison staff need to be aware of to ensure both the prisoner’s and their own safety. In order to get some indication of the prevalence of mental health issues in Northern Ireland prisons, we reviewed data relating to committals over the four-year period 2014 to 2018. This supports the view that there is a high prevalence of a range of often co-existing vulnerabilities amongst new prisoners. Over one-third reported they were engaged with mental health services at the time of their committal (Figure 9.

2.13 The high levels of existing vulnerabilities disclosed by new prisoners during committal can be compounded by a perception of being unsafe in prison. The process of leaving the community and entering prison can be enormously stressful in itself. It also tends to exacerbate any existing issues. A key challenge for the prison authorities is managing highly distressed, newly arrived prisoners safely.

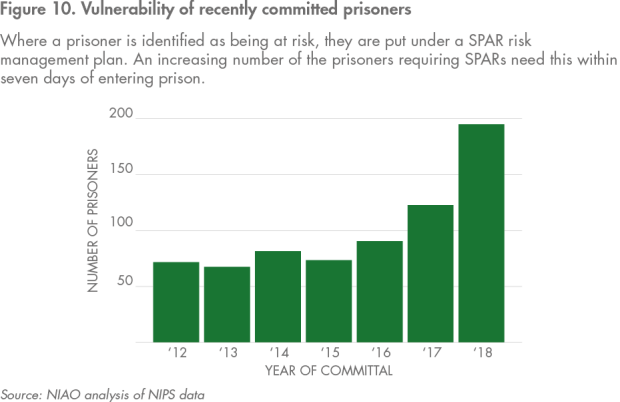

2.14 The process that has been used to manage prisoners at risk is known as SPAR. SPAR is a set of standard operating procedures derived from NIPS’s Suicide and Self-Harm Prevention Strategy. These procedures amount to a short-term crisis management tool, designed to respond to the needs of those deemed to be at risk of suicide or self-harm. Over the last seven years, a growing proportion of SPARs have been applied to prisoners in the first seven days following committal, highlighting the high levels of distress and vulnerability amongst this population (Figure 10).

2.15 In addition to the committal process, newly arrived prisoners are also subject to an assessment by the SEHSCT, which provides healthcare services across all Northern Ireland’s prisons. This is similar to the Prison Service procedure, consisting of a series of questions designed to gather important information about the individual. However, the SEHSCT process is more focused on identifying specific medical issues that affect the individual and require care.

2.16 The SEHSCT was unable to provide detailed records of the information gathered during this process for our review. The results of a health needs assessment exercise carried out in 2016, which analysed all committals over a two-week period in September 2015, found a similar prevalence of issues amongst newly arrived prisoners to Prison Service data (Figure 9), with 31 per cent of new prisoners referred to the prison mental health team upon arrival.

2.17 The vast majority of prisoners who require mental health services can have their needs met within prison. The health needs assessment reported there were 240 patients on the prison mental health service caseload in October 2015. We were not able to verify the current mental health caseload, but other records relating to the ongoing review of arrangements for vulnerable prisoners reported 443 prisoners as having a mental health issue at 1 October 2017, around 30 per cent of the prison population.

2.18 The healthcare facilities available in prison are not equivalent to a full hospital site. Whilst they are sufficient to meet the health needs of most prisoners, some of those with the most significant needs may need transferral to a medical facility. Typically, around 20 prisoners per year transfer to the Shannon Clinic for more intensive mental health care. Should their treatment be effective, they will be returned to prison and managed within that setting whilst they remain under sentence.

Community Sentences

2.19 At the beginning of a community sentence, the majority of offenders undergo an ACE assessment. ACE is a tool used to assess the likelihood that an offender will reoffend within a two-year period. The assessment includes a two-fold consideration of the extent to which a range of different factors cause an offender problems in their day-to-day life and the extent to which these problems may be a contributory factor in the person’s offending behaviour.

2.20 Between May 2014 and April 2018, around 8,600 offenders were subject to an ACE assessment. These were mainly those serving a community sentence, but around 1,500 were serving a custodial sentence. Whilst not a clinical assessment, the results reflect the professional judgement of a Probation Officer on the impact of a range of issues upon the offender’s life generally, and upon the risk of their reoffending. In respect of mental health, the results show that a high proportion of offenders are affected by general mental health issues, and for most of these people these problems contribute in some way to their risk of reoffending (Figure 11).

Part Three: Issues affecting justice system users with mental health issues

3.1 This part of the report identifies the key ways in which the justice system works that can hinder the achievement of positive outcomes for offenders with mental health issues. This is not an exhaustive list but it highlights those areas where the interface between the justice process and other public services, particularly health, have not worked effectively. Our focus is on two key interfaces between health and justice:

- the prevalence of issues amongst those in the community who come into contact with the PSNI; and

- the prevalence of issues amongst those who receive custodial sentences, for whom mental health issues can be a key barrier to effective rehabilitation.

Police officers respond to incidents which are essentially health rather than justice related

3.2 Officers responding to incidents are often confronted by situations requiring skills and experience outside their training. Responding officers are expected to deal quickly and effectively with complex medical issues whilst lacking key information about the individual’s history. Given that such events can occur late at night and outside normal office hours, officers frequently find it difficult to contact key health and social care staff who may have knowledge of the individual.

3.3 Under the Mental Health (Northern Ireland) Order 1986, officers have three choices in such situations:

- detain the person and convey them to a place of safety (either a hospital emergency department or police custody);

- do not formally detain the person, but accompany them to a hospital emergency department; or

- leave the scene without taking any further action.

3.4 Officers generally consider the third of these options to be unrealistic. Leaving the scene without taking action, even if justifiable given the information available at that time, could have serious consequences, particularly if the situation should deteriorate shortly after their departure.

3.5 Under current legislation, officers are not empowered to detain an individual who is experiencing a crisis within a private premises and where there has been no criminal offence. This means that officers responding to an incident where they have no statutory powers can often spend a long time encouraging the individual to seek care, due to concerns about their welfare.

3.6 Whether an individual is detained and brought for medical care or attends voluntarily, the end result is effectively the same. When arriving at hospital, the individual is triaged and prioritised in the same way as anyone else attending the service. They can therefore encounter the regular delays that occur in emergency departments. The accompanying officers will wait with the person, meaning they are unavailable for other policing duties. Due to the security context in Northern Ireland, the PSNI may also have to despatch more officers to the hospital grounds to provide additional security. This can mean up to four officers being unavailable for general service for up to 30 hours. This has huge implications for the level of service that can be provided to the rest of the community.

3.7 The waiting period can be a volatile situation - the individual may be, at best, attending reluctantly or, at worst, may not wish to receive care at all. Any frustration may be exacerbated by a long waiting time. The individual may themselves be volatile and their behaviour erratic. Incidents often occur, such as assaults on medical staff or the police (Case Study 1). The officers involved have little guidance currently on how to deal with offences committed by people clearly mentally distressed at such times. Officers told us that there was not a consistent approach amongst officers to responding to such incidents, but we were also informed that the PPS has recently invited the PSNI to contribute to a project intended to develop appropriate guidance.

Case Study 1: PSNI conveying individuals in crisis to place of safety

The PSNI received a report of a missing person, who was high risk and had reported suicidal thoughts. Police subsequently located the individual and took them to Knockbracken Wellbeing and Treatment Centre for a psychiatric assessment.

While the individual was initially compliant with officers, they subsequently decided that they wished to leave before the assessment was complete. When officers attempted to persuade the individual to remain, they became agitated and struck three of them.

The individual was then arrested and brought to police custody, where they assaulted two members of the custody team.

The individual has been charged and is being prosecuted in relation to the five incidents of assault.

3.8 While the PSNI sees this issue as a significant strategic one, it acknowledges the need for a more detailed understanding of the overall impact on its operations. Preliminary assessments by the PSNI that indicate potentially large operational impacts are consistent with the experiences of other UK police forces. In November 2018, HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire Rescue Services in England and Wales (HMICFRS) described the widespread involvement of police officers in such incidents across the UK as a “national crisis which should not be allowed to continue”.

3.9 In HMICFRS’s view the cause of this crisis is that the funding pressures on the health system across the UK have affected the ability of mental health services to meet the needs of many vulnerable people. Police forces and officers are being used to plug this gap. This has not only placed significant operational resource demands upon police forces, it has also failed to provide the service that these individuals experiencing crises need – these people need the support of health experts, capable of providing necessary medical attention.

Healthcare arrangements for people detained by the police have been costly and have not delivered the best outcomes

3.10 If an individual is arrested and appears to have a medical issue, the Custody Sergeant summons a Forensic Medical Officer (FMO) to attend the custody suite to make an assessment (Figure 5). FMOs are independent GPs, contracted by the PSNI on a call-off basis, to provide this service. Should the assessment determine a need for medical treatment of any kind, the individual is taken to a hospital emergency department. Once treatment is received the individual is brought back into police custody for interview. The process of taking detained persons to hospital is subject to the same inefficiencies as outlined at paragraphs 3.6 to 3.7.

3.11 The FMO model of medical assessment is expensive compared to nurse-led models used elsewhere. Analysis by the Public Health Agency found that the cost of delivering health care in custody suites in the Greater Manchester area, which used a nurse-led model, was around one quarter of the cost of the FMO model used in Northern Ireland, despite there being nearly twice as many detentions here than in Greater Manchester.

3.12 Despite the relatively high cost of the FMO model, it has not been able to deliver consistently two main objectives of police custody healthcare:

- The assessment of an individual in custody is an opportunity to identify individuals who may have mental health or other needs, but are not engaged with appropriate services. Under the period when the FMO model has been used there has not been an effective mechanism to facilitate these referrals.

- The information gathered during the assessments performed by FMOs should be useful to other health and justice organisations who will be in contact with the suspect as they progress through the justice system.

3.13 A current reform initiative (the Transformation of Custody Healthcare pathfinder) aims to develop a healthcare model for police custody based around the permanent presence of nurses in custody suites and is currently being tested in Musgrave Station, Belfast. This is discussed further in Part 4 (Figure 17).

3.14 Regulatory inspections of the prison system have regularly criticised both the NIPS and the SEHSCT for failing to identify vulnerable prisoners during their initial committal to prison. The NIPS and the SEHSCT argue that the inconsistent quality of the documentation of FMO assessments provided to them is a significant factor. An SEHSCT review reported regular failures to meet national standards of record keeping, which impaired the ability of prison staff to use the information to identify important risks.

Key decisions during the prosecution process are limited by an inadequate range of options

3.15 Once a case arrives at court for prosecution, the prosecutor is required to take account of any relevant change in circumstances which may necessitate reviewing whether to discontinue the proceedings against the defendant, or potentially diverting the case from the courts. Such changes can include issues related to mental health. However, responsibility for case management at court lies with the judge. During the course of a case, the judge will make a number of decisions that can have a significant impact upon the defendant’s wellbeing. Trial judges make these decisions entirely independently of other justice organisations. The two main decisions are whether the individual should be held on remand during a court trail and, if convicted, the nature of the sentence that should be imposed.

Remand

3.16 Remand is a process whereby a defendant is held in custody during the prosecution of that case. Remand prisoners are generally subject to the same regime as convicted offenders. They will be escorted from prison to court each day they are required to attend, and brought back to prison at the day’s end.

3.17 In some cases, a defendant may be held on remand specifically for a mental health assessment (commonly referred to as Article 51 detentions). Since January 2017, 23 individuals have been committed to prison using this process. Whilst this is a relatively small number, this practice is entirely inappropriate and does not serve the health needs of those individuals. Instead, where such assessments were required they should be delivered within a health setting. The SEHSCT told us that in the vast majority of these cases the assessment did not result in a diagnosis that would support the need to detain the individual on health grounds, however we were not able to review evidence of this.

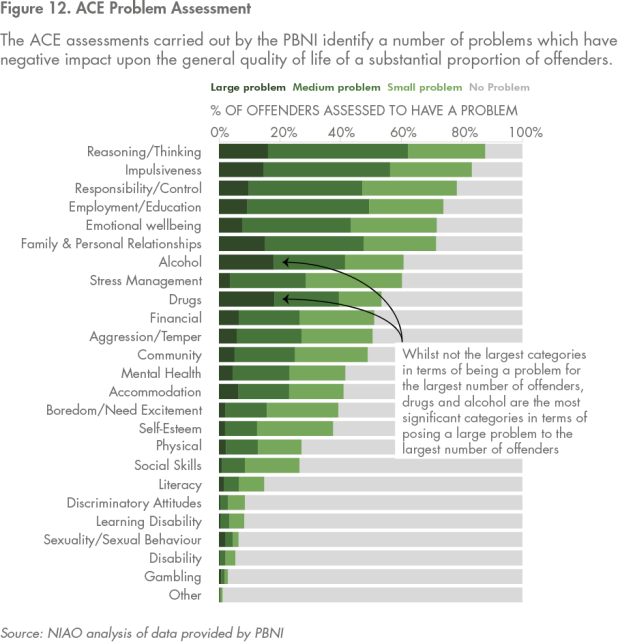

3.18 In other cases, the link between vulnerability and decisions to use remand may be less explicit. ACE assessment results cover a wide range of factors and show a high prevalence of a range of vulnerabilities and problems amongst those assessed (Figure 12).

3.19 In cases where an individual presents with an apparent general sense of vulnerability and poor connection to key support services, there may seem no effective alternative to the use of prison as a short-term place of safety, in the absence of other options (Case Study 2). However, justice and health professionals consider that this approach delivers poor outcomes for the individual.

Case Study 2: The use of remand as a place of safety

Police received a report concerning a woman acting in a potentially suicidal manner on a bridge. The responding officers took the woman to a ital emergency department where she refused treatment.

The woman’s actions were determined to be in breach of existing bail conditions to which she was subject. As a result, the woman was brought to court for a hearing, where she admitted being in breach of her bail conditions.

At the hearing the PSNI requested that the woman be detained on remand, primarily as a safety measure. Whilst recognising the dilemma the PSNI officers felt themselves to be in, the judge rejected the request to hold the individual on remand on the grounds it would not provide a positive outcome. Whilst making his ruling the judge voiced his dissatisfaction at the level of care available to the woman involved, and people in similar circumstances, and criticised an attitude of leaving the justice system to resolve such difficult cases.

Sentencing

3.20 Following conviction a defendant is sentenced by the trial judge. This decision is made within a legislative framework providing different options in respect of different offences. The judge also considers a number of different factors, such as the offender’s criminal history and their apparent level of contrition, in picking the most appropriate option. The information provided to the judge will include details of any identified mental health issues. Custodial sentences tend to be used in respect of the most serious offences, or for those individuals who may not have committed serious offences but have a significant offending history and show no sign that less significant sentences in the past have had an impact upon their conduct.

3.21 The vast majority of custodial sentences imposed in Northern Ireland are for a relatively short period of time (Figure 13). This is despite a general consensus amongst justice organisations that short sentences do not support effective rehabilitative work. Many of the stakeholders we engaged with during our fieldwork referred to the absence of step-up/step-down facilities as a key gap in the current framework of options. Such facilities would offer a level between community supervision and prison detention, where offenders could be more effectively managed.

Providing a healthy prison environment for vulnerable offenders is difficult

3.22 Given that custodial sentences are imposed upon those committing the most serious offences and upon the most prolific and consistent offenders, it is important that the environment in which they are detained is sufficiently safe and healthy to support effective rehabilitative work. This has proven challenging to the justice system.

3.23 The basic structure of prison life, both in terms of the physical environment and the daily social regime imposed on prisoners, can pose a threat to an individual’s mental wellbeing. The needs and vulnerabilities of the prison population tend to represent a high concentration of the needs and vulnerabilities that affect the general population. For those people with underlying mental health issues who enter prison, there is a risk that the stresses of prison life can cause distress and a deterioration in their condition. Many of the strategies recommended to a person in the general community to help manage their condition are hard to apply within a prison environment. As a result, the NIPS works alongside a wide range of statutory and community partner organisations to provide mental health related services and interventions for the prison population. Whilst the NIPS is involved in the delivery of some therapeutic programmes, responsibility for the provision of mental health and addiction services rests with the SEHSCT.

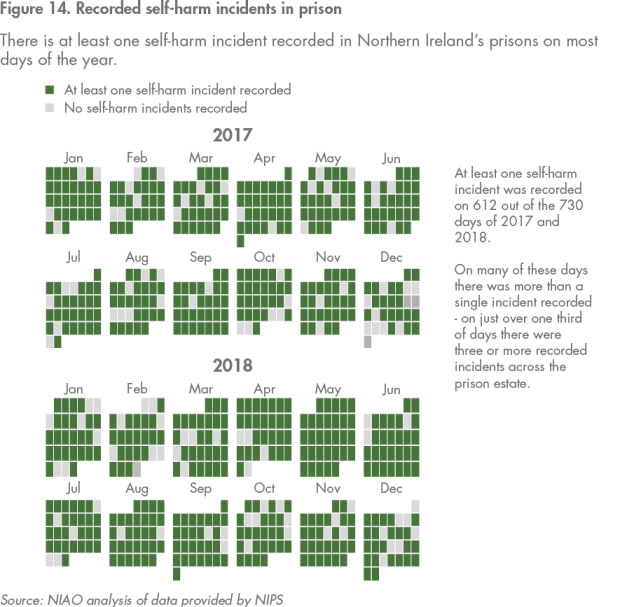

3.24 At the most basic level, ensuring a safe and healthy environment depends on the application of intelligent risk management and protective processes for prisoners considered vulnerable or at risk of harm. Since 2011-12, there have been 18 confirmed or suspected suicides amongst the prison population and 5,217 recorded incidents of self-harm. Self-harm is a near daily occurrence, with more than one incident being recorded on most days (Figure 14).

3.25 Self-harm is a focus of significant public and media interest but is also a complicated issue. NIPS has consistently asserted that it should not be assumed that all those who self-harm in prison are vulnerable - there are myriad reasons why people in prison self-harm, not all of which relate to vulnerability or mental health issues. Furthermore, self-harm incidents can range from the infliction of superficial to catastrophic injuries. Current processes for recording of self-harm incidents within prison do not include an assessment or recording of the seriousness of incidents, meaning it was not possible for us to investigate this issue more thoroughly.

3.26 Beyond immediate risk management, a safe and healthy prison also depends on managing a number of other environmental issues effectively. These include the provision of health care services; a culture where prisoners are treated respectfully; the availability of purposeful activities; and a robust system to guide prisoner’s rehabilitative work. Failure to ensure these makes it more likely that prisoners will become vulnerable and more difficult to support.

3.27 Whilst responsibility for the overall environment lies primarily with the NIPS, delivery of the various elements involves a number of different statutory and community organisations. For example, the NIPS and the PBNI deliver jointly the Prisoner Development Model that directs the rehabilitative work prisoners complete in custody. The SEHSCT is responsible for the provision of healthcare for prisoners.

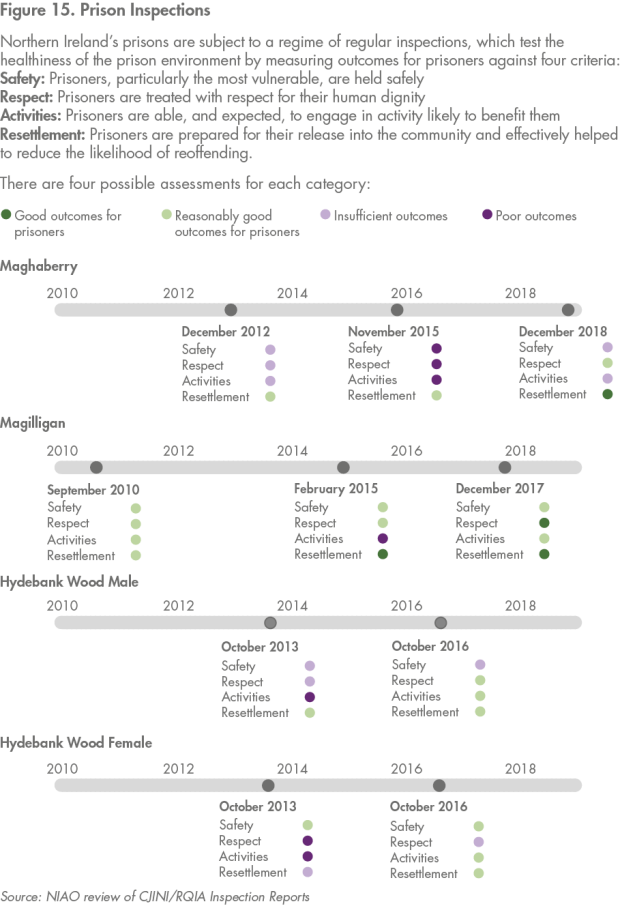

3.28 The extent to which a safe and healthy environment is provided is subject to regular inspections conducted jointly by the CJINI and HM Inspectorate of Prisons, with support from the Regulation Quality and Improvement Authority (see Figure 15). Historically, these inspections have raised concerns about the safety and health of the prison environment.

3.29 In particular, the inspections of Maghaberry, Northern Ireland’s largest prison, have consistently identified a range of issues:

- inadequacies in the committal process and failure to provide medication to new prisoners in the first days after they enter custody;

- high levels of violence and bullying;

- the availability of drugs;

- the number and quality of purposeful activities available to prisoners to develop themselves; and,

- a lack of sophistication in the implementation of the SPAR system used to support and protect vulnerable prisoners.

They have also regularly included issues around the provision of general and mental health services and medication to prisoners.

3.30 A key historic issue has been a difficult working relationship between the NIPS and the SEHSCT over much of the last decade. The delivery of healthcare in prison is complex, and basic medical practices can be difficult to manage within such a unique environment. For example, there are significant risks in the distribution of certain medicines to prisoners, which may be abused by the prisoner or put them at risk of bullying by other prisoners keen to extort their medication. Overcoming the obstacles depends upon the SEHSCT and the NIPS being able to work together to devise agreed solutions. For many years this proved difficult, affecting all areas of health care, including mental health.

3.31 While the Maghaberry report in 2015 was an undeniable low point, it also served as a catalyst for substantial efforts to improve the quality of the prison environment and the working relationship between the Prison Service and the SEHSCT. Stakeholders identified significant improvements and a far more constructive relationship. A variety of initiatives have been implemented across the prison estate and recent inspection reports have demonstrated improvements in outcomes for prisoners in at least some areas, compared to the previous inspection report for all prisons. The most recent full inspection of Maghaberry reported significant improvements across all four healthy prison criteria, compared to 2015. The foreword to the Inspection Report commends the work undertaken to date, and notes that it is rare to see a prison make this level of progression.

Many offenders leave the justice system vulnerable or at risk and pathways to support services can be problematic

3.32 The final stage of the justice process is when the offender has completed their sentence and resettles in the community. It is the system’s objective that individuals departing are successfully rehabilitated and will not reoffend.

3.33 However, a substantial number of offenders reoffend within one year of being released from custody, or within one year of being given a community supervision sentence. The most recent analysis completed by the Department, which covers both adult and youth offenders, found 41 per cent of those who had completed a custodial sentence reoffended within one year, and 35 per cent of those who received a community sentence reoffended within one year.

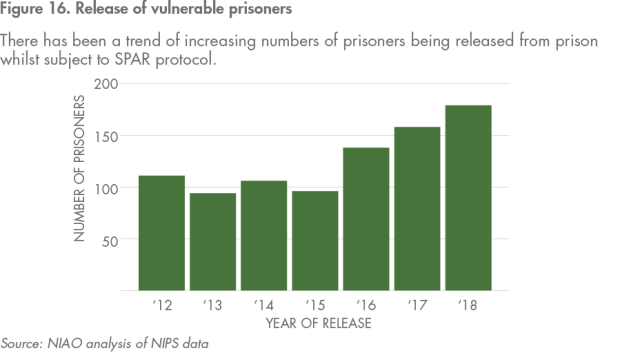

3.34 The vast majority of offenders serve their sentence over a relatively short period of time. This provides little time for rehabilitative or psychological work to address their offending. While not quantified, vulnerable prisoners regularly leave prison unexpectedly, with no means of planning for their departure. This applies, for example, to those held on remand whose court case collapses unexpectedly. Overall, there has been a trend of increasing numbers of people leaving prison whilst under a SPAR (Figure 16).

3.35 Some offenders may lack supportive family or social networks to help them through the early stages of their release. This can cause significant concern to the authorities who may have no effective course of action in these circumstances (Case Study 3). Currently, there is no outreach system for health or social services to help manage the safe return of these individuals to the community.

Case Study 3: Continuity of care

Prison staff had serious concerns about the impending release of a prisoner considered to be at risk and cared for under the SPAR process. Normally healthcare staff would contact the individual’s next of kin or GP to make them aware of the issues that affected the person whilst in custody. However, in this particular case, the prisoner was not registered with a GP and a next of kin had not been recorded or provided.

In similar circumstances in the past, prison staff had informed the PSNI of the release, and officers had called in on recently released prisoners. However, the PSNI’s ability to do this is constrained by operational pressures at the time such notifications are presented. On this occasion officers were not able to visit the individual.

3.36 A number of issues can affect how prisoners who may not be at risk, but who continue to be affected by mental health issues and who would benefit from ongoing treatment or engagement with key services, are able to access these services after departure from the justice system. Some ex-offenders may have fairly low-level mental health issues unrelated to a diagnosable clinical condition, but which still affect their ability to live productively in mainstream society and avoid becoming involved in criminal activity. Within prison, these people may have been receiving higher levels of treatment or intervention than would be provided in the community for someone with similar problems. Practitioners described prisoners referred for further work after their release being assessed and almost immediately discharged by local community health services as a regular occurrence.

3.37 Where an individual has a diagnosed medical condition, they should be able to access general health services. However, even those who continue to have access to health and social services can experience a steep drop off in the intensity of their contact. Leaving prison to return to a chaotic living environment or lifestyle can make even basic attendance at health appointments very challenging. In prison, individuals who do not attend a session may have someone come to their cell to coax them into going. This level of outreach is unlikely in the community. If the individual begins to disengage from key services in the community, there can be an increased risk of regression in their condition and the undoing of progress which had been made while in custody.

3.38 A common barrier is when an individual is not registered with a GP and does not have permanent living accommodation. An individual must have an address in order to register with a GP, with the GP then acting as the gateway to other health services. Analysis of the information gathered by Prisoner Needs Profile questionnaires completed in 2017 reported that nine per cent of the prisoners who responded said that they were not registered with a GP when they entered prison. Nineteen per cent reported they were either homeless or living in a hostel at the time they entered prison, and 26 per cent that they had no accommodation to go to upon release.

3.39 We have no equivalent data covering the point of departure from prison. Nevertheless, it is widely accepted that there are a number of offenders who enter prison with no fixed address, and who struggle to find suitable accommodation when released. Their behaviour and other issues can make them too much of a challenge to accommodate in hostels or sheltered accommodation, which may not have the necessary level of expertise to deal with these often complex individuals safely. This can leave them without the means to access the essential support services, needed to build upon any progress that had been made while in custody. The need for suitable facilities to house such challenging individuals was a recurring theme throughout our review.

Part Four: Managing an effective reform process

4.1 This part of the report describes the approach the justice and health systems have taken to address issues identified in this report. These reforms are to be welcomed, particularly the commitment of the justice and health systems to work in collaboration. However, there are key areas where further work is needed to develop this progress into a more effective, outcome-based response.

The justice system has begun to implement reforms involving significant collaboration with health

4.2 The launch of the Outcomes Delivery Plan in 2018 represented a new approach to delivering public services in Northern Ireland, placing an emphasis upon the outcomes that public services are intended to achieve, with less emphasis on individual organisational inputs, processes and outputs. A key intended outcome is improving the way in which the justice system interacts with key demographic groups that the system, as it currently works, does not serve well. This includes offenders with mental health issues.

4.3 Within the Delivery Plan, the Department of Justice has primary responsibility for the delivery of Outcome 7: ‘we have a safe community where we respect the law, and each other’. There are two main components of the Plan related to the issues raised in this report: the adoption of a Problem Solving justice model, and implementation of the Health in Justice Strategy and Action Plan.

4.4 Problem Solving Justice is a framework for tailoring certain aspects of the justice process to ensure that it is effective in meeting critical needs of key users. Failing to address these needs means that they can act as a barrier to effective rehabilitation of the offender. Mental health issues are one such area of need.

4.5 The Health in Justice Strategy and Action Plan is the result of an intensive joint effort between the Departments of Justice and Health, and a range of agencies within both sectors, to ensure that those in contact with the justice system received the highest attainable standard of health and wellbeing.

4.6 Alongside these reforms, the Department is also undertaking a review of sentencing policy in Northern Ireland. Currently, proposals are being developed with the intention of a public consultation exercise to be completed in 2019. This consultation will include consideration of the potential benefits of community disposals, including how they compare to short-term custodial sentences (see paragraph 3.21).

4.7 Figure 17 provides an overview of some of the most significant individual operational reforms currently being implemented in the context of this report. This list is not exhaustive, but provides evidence that the system is attempting to address issues arising throughout the justice process.

Figure 17. Reform Initiatives

|

Reform Initiative |

Lead Agency |

Detail |

Cost |

Expected Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mental Health Triage |

PSNI, SEHSCT, NIAS, PHA |

The establishment of a triage team consisting of a police officer, a community psychiatric nurse and a paramedic who will be available to respond to reported incidents of people experiencing emotional crisis. Currently being piloted in the SEHSCT area. |

£930,000(2017-21) |

It is expected that this model will prove a more cost effective method of responding to emotional crisis incidents than relying primarily on the PSNI. It is also expected this model will be more effective in directing individuals to relevant care pathways. |

|

Transformation of custody healthcare |

PSNI, BHSCT, PHA |

The development of a healthcare model for police custody based around the permanent presence of nurses in custody suites, including specialist mental health nurses. |

£450,000(2018-19) |

Improved care pathways for detainees in need of immediate emergency care, as well as improved referral pathways for individuals requiring mental health care. |

|

Community Support Hubs |

DOJ |

Support Hubs will be established in each local government area, bringing together key professionals from justice and health organisations to share information about vulnerable individuals who present repeatedly to organisations, in need of help. |

£91,000(2018-21) |

The Hubs will be able to support early interventions to direct people away from the justice system towards other statutory and voluntary organisations who can provide the individual with support to improve their circumstances. |

|

Enhanced Combination Orders (ECOs) |

PBNI, OLCJ |

An attempt to develop an intensive community sentence within the existing legislative framework, which can act as an effective alternative to short custodial sentences, which are considered to be ineffective in supporting rehabilitation of offenders. |

Unknown |

The ECOs were expected to provide an effective community-based alternative to short custodial sentences. Still in pilot, and whilst some evaluation has been undertaken to date, this has not been comprehensive or conclusive. |

|

Mental Health courts |

PBNI, DOJ, NICTS |

At the time of writing the proposals for the mental health court remain in development. |

Unknown |

Whilst still in development, it is expected that the Mental Health courts will support new sentencing options appropriate for offenders with mental health issues, and enable earlier engagement with such offenders before they fall into a cycle of reoffending. |

Effective long-term reform requires collaboration and realignment of key services, both of which are difficult to achieve

4.8 While collaborative reforms are welcome, securing key agreements between the justice and health systems has often been difficult and involved significant delays. For example, the Health in Justice Strategy and Action Plan originates from a recommendation in the Prison Review Team report in 2011. Whilst a draft was completed in 2016, Ministerial approvals had not been obtained prior to the Assembly being dissolved in early 2017. Delays have also impacted on the Review of the Arrangements for Vulnerable Prisoners, announced by the Ministers of Health and Justice in late 2016, but which remains a work in progress.

4.9 The justice and health systems in Northern Ireland are highly complex and getting various parts of the different systems to work collaboratively is extremely challenging. The absence of an Executive and fully functioning Assembly has undoubtedly hindered progress on the reforms, but the delays are symptomatic of a more general issue of public bodies not collaborating effectively.

4.10 At an operational level, an evaluation of the ECOs pilot by the PBNI illustrates how individual reforms are reliant upon key structural elements within other public services working effectively (Figure 18). In particular, the rehabilitative work in the justice system places heavy reliance on other areas such as health, housing and employment. Where these services are not ready to work effectively with new practices, they limit the potential impact of these reform programmes in terms of rehabilitation and reoffending.

4.11 Structural obstacles to collaboration remain a continuing threat, even in areas where positive progress is made. Falling back into old practices and poor outcomes is a persistent risk that needs consistent careful management. For example, in May 2018 the Criminal Justice Inspector reported on a deterioration in the quality of the collaborative working between the Prison Service and the PBNI in delivering the Prisoner Development Model, having previously welcomed this initiative.

4.12 A feature of previous reform initiatives is that there is a high level of dependence on the personal relationships of key staff at partner organisations. The quality of these relationships has a significant impact on the quality of the engagement between organisations. A heavy reliance on these relationships is inherently volatile and increases the risk of regression should the personnel involved change, or relationships deteriorate.

4.13 Finally, recognition must be made of the challenging economic climate in which reform initiatives are being designed and implemented. The impact of public expenditure constraints over the last decade cannot be overstated and there remains a high degree of uncertainty around funding in the short to medium term. Developing new models of service delivery can increase costs in the short-term and any costs or savings achieved can be unevenly balanced between different justice organisations, and between the justice and health systems. Apportioning these will be difficult, given the general financial pressure both systems currently face.

Figure 18: Enhanced Combination Orders (ECOs) Evaluation

The Enhanced Combination Order pilot exercise commenced on 1 October 2015. ECOs were designed as part of an attempt to develop an intensive community based sentence that could serve as an alternative to short custodial sentences. All the offenders involved were required to:

- complete unpaid work within local communities at an accelerated pace compared to a standard community sentence;

- participate in victim focused work;

- undergo assessment and, if appropriate, mental health interventions with PBNI psychology staff. If issues were identified, there would be a treatment plan or referral to an appropriate health provider as part of an intervention;

- complete an accredited programme, if appropriate; and

- undertake intensive offending-focused work with their Probation Officer.

In June 2017, the PBNI completed a preliminary evaluation of the results achieved for those who had undertaken the programme at that point. This identified a number of key areas where the ability to support the rehabilitation of offenders with mental health or other complex needs depended on certain structural factors and effective links with other public services and community organisations:

- Access to mental health services was a barrier to client progress. There were particular difficulties with participants who didn’t have formal diagnoses. Additionally, GP referrals could take a long time and cases where individuals missed appointments for either health or addiction services could lead to discharge and set back the client’s progress. In some cases there was a feeling amongst staff delivering the ECOs that there was a lack of services in the community for participants.

- There were difficulties in securing appropriate community service placements. In addition to a perceived reluctance amongst some organisations to take particular participants, it was felt that mental health and lifestyle issues were barriers to placement. Some staff reported that they felt that a lack of resources was hindering the establishment of links with organisations who would potentially be willing to accommodate participants.

- ECOs involved the imposition of significant expectations on participants from the outset. Participants frequently had complex needs and chaotic lifestyles. In such cases there was a need to prioritise their work so they weren’t overwhelmed, and resist the temptation to rush through the requirements. Yet the delivery of the programme was affected by funding uncertainties that led to participants being signed up to multiple initiatives/interventions at times when funds were available, and not necessarily when most needed or beneficial, due to fears funds would not be available at a later date.

Providing a framework where reforms can be effective will require strong and consistent leadership

4.14 Building and managing a collaborative approach to the delivery of PfG outcomes requires dedicated staff with specific skills to coordinate the activities of justice and health bodies. The cross-cutting nature of the issues and the necessity of realigning services for offenders with mental health issues across departmental and organisational boundaries, highlights the need for these staff to be supported by the senior leadership of the justice and health systems.

4.15 There is currently no formal leadership group responsible for coordinating a joint response to mental health and other broad Problem Solving Justice issues. The Criminal Justice Board (CJB) performs such a role in respect of cross cutting issues within the justice system in relation to justice specific issues, for example, taking a lead in coordinating the response to the issue of avoidable delays in the justice system. The Pathfinder for Healthcare in Police Custody provides a useful example of the potential that the commitment of strong high-level leadership can have in overcoming barriers that are hindering the development of a cross-cutting service at the level of an individual project (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Transformation of Custody Healthcare

The creation of the Pathfinder for Healthcare in Police Custody provides an illustration of how top-level buy-in can overcome barriers and facilitate reform initiatives. The project was developed by a Regional Task and Finish Group. This Group consisted of officials from both health and justice organisations. A Steering Group, consisting of the Accounting Officers from Health and Justice and the Chief Constable, was subsequently established to provide oversight of the Task and Finish Group’s work.

The organisations involved in the project share a view that the oversight from the Steering Group has brought continued momentum to the programme of work, ensuring that significant challenges are addressed in a timely manner. The Group has benefited from applying learning gained during the transfer of prison healthcare to the SEHSCT, as well as benchmarking with similar programmes of work in England and Scotland.

4.16 A high-level leadership group being able to provide oversight, challenge and direction for the implementation of reforms across the entire justice system holds significant value. The positive outcomes achieved by high level involvement in the pathfinder project have led to initial discussions around the formation of a similar group to oversee other reforms related to the interface between the health and justice systems. This would be a welcome development.

Recommendation 1

Establish a justice/health leadership group, with dedicated staff with specific skills to coordinate the activities of justice and health bodies to embed cross-sector communication, alignment, and the collaboration necessary to address mental health and other Problem Solving Justice issues.

There is a need for greater clarity on what success looks like and how progress will be measured and monitored

4.17 The objectives of the current reform programme are consistent with the principles of the PfG and the Outcomes Delivery Plan. The key PfG indicators that will be used to measure progress against the PfG are those related to Outcome 7. These represent long-term strategic objectives for the justice sector. Achieving them will depend upon the aggregation of a number of different operational areas delivering positive outcomes (Figure 20).

Figure 20. Outcome 7 Indicators

The aspiration expressed in Outcome 7 is that we have a safe community where we respect the law and each other.

The extent to which this is being achieved will be measured according to:

- the proportion of the population who were victims of crime as measured by NI Crime Survey;

- the criminal reoffending rate;