Abbreviations

JJC Juvenile Justice Centre

OBA Outcomes Based Accountability

PfG Programme for Government

PPS Public Prosecution Service

PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland

YJA The Agency/YJA - Youth Justice Agency

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. In Northern Ireland young people aged between 10 and 17 may be held criminally responsible for their actions. The youth justice system is responsible for working with those who offend, their families and carers to help prevent them reoffending.

2. In 2016, an appraisal of how the system in Northern Ireland was working was completed – the Scoping Study into Children in the Justice System. Shortly after this in 2017, we published Managing children who offend. Our report focused primarily on the responsibilities of the Department of Justice (the Department) and the Youth Justice Agency (the Agency) within the wider system, and identified three strategic issues:

- the need for a specific strategy to coordinate the delivery of youth justice services, policy and interventions;

- the need for better measurement and reporting on the impact that the services delivered by the Agency had on the young people it worked with; and

- the need to develop the capacity to identify and apportion the costs of different services delivered by the Agency.

In this report we follow up the progress made by the Department and the Agency since 2017.

3. The youth justice system is in the early stages of a major reform programme, guided by the recommendations made in the Scoping Study. Progress towards developing a programme of action based upon these recommendations was delayed by changes in Ministerial priorities following an Assembly election in May 2016, and subsequently by the absence of a functioning Assembly between 2017 and 2019. In early 2019 the Department and Agency agreed a new strategic plan to implement the changes envisaged in the Scoping Study– Transitioning Youth Justice. Failure to address the issues identified in our previous report is likely to present a significant risk to implementing reform successfully.

Key issues

The youth justice system has been developing new approaches to working with young people who offend

4. Despite the delays which have affected the implementation of a transformation programme for youth justice, the system has begun to work with children in new ways that are more consistent with the vision established by the Scoping Study. Over the course of the last decade the number of young people held in custody has fallen substantially. New approaches for dealing with low-level and first time offences have been developed, and account for a greater

proportion of young people that the Youth Justice Agency works with each year. These approaches are intended to provide quicker resolution, and also earlier identification of cases involving young people who may be at a high risk of falling into a cycle of repeated offending and multiple contacts with the justice system.

Reoffending rates have remained relatively stable since our last report

5. The data shows a general decrease in the volume of young people being dealt with through the traditional formal justice process, but reoffending rates for those that are have remained generally stable year on year. In common with overall reoffending rates, other related significant trends have remained relatively consistent: those who do reoffend tend to do so relatively quickly after exiting the justice system, and a small proportion of prolific offenders go on to commit a significant number of further offences.

Delays within the justice system are detrimental to the young people involved

6. Where a young person falls into a cycle of repeated offending and contact with the justice system this can have a hugely negative impact upon long-term life outcomes, health, wellbeing and welfare. It is therefore imperative that they are dealt with appropriately, provided with any support they need and exit the justice system as quickly as possible. Despite the decreasing volume of cases being processed at court, there is no evidence of a significant improvement in the timeliness of completion, and the most recent figures show generally deteriorating performance since 2014-15.

Children in custody often have the most significant care needs

7. Almost half of young people admitted to Woodlands Juvenile Justice Centre (JJC) in 2016 were involved with mental health services and had a mental health diagnosis. They also had major educational deficits, including moderate to severe learning difficulties, lack of engagement with mainstream education and a significant number with Special Educational Needs Assessments. More than 75 per cent were not currently in any form of education or training. Despite the challenges these often severe levels of need present to staff, the level of care and support provided to young people in the Woodlands JJC has been recognised for its consistently high standard.

Further work is required to fully implement our original recommendations and support an effective reform process

8. Transforming and redesigning complex public services like those provided by the youth justice system is inherently difficult. The Department and the Agency have made progress since our initial report to manage and deliver an effective reform programme. However, the work to date does not meet the strategic needs identified in 2017 because:

- Transitioning Youth Justice is not a fully developed transformation strategy;

- the system does not have a means of measuring and reporting the impact its work has on the young people it deals with; and

- there remains insufficient understanding of costs throughout the youth justice system.

Summary of recommendations

1. The vision outlined in Transitioning Youth Justice should be developed further into a comprehensive strategy. This would:

- provide clarity to stakeholders on the evidence base that supports the proposed reforms;

- define the benefits that will be achieved from successful change; and

- establish a framework for monitoring success.

2. The Agency should continue to develop its performance reporting regime, with greater focus on the impact of its work with children and families, in line with the principles of Outcomes Based Accountability (OBA).

3. The youth justice system should work together to further develop its financial management information in order to better understand the costs of whole-system activities and to link resource inputs to outputs and outcomes.

Overall conclusion

9. In 2017 we highlighted how the ability of any public service to demonstrate it was achieving value for money hinged on its ability to measure, report and analyse the cost of the various activities that taxpayers were funding, and the benefits that resulted from those activities. Progress has undoubtedly been made, but further work is required to build management systems that are capable of demonstrating the value for money of the youth justice system. Until then, we cannot conclude that the system delivers value for money.

Part One: Introduction

The youth justice system

1.1 In Northern Ireland young people aged between 10 and 17 may be held criminally responsible for their actions. The youth justice system is responsible for working with those who offend, their families and carers to help prevent them reoffending. The system is made up of a number of different organisations, each with its own role and responsibilities.

Figure 1. Organisations involved in the youth justice system

|

Organisation |

Responsibilities |

|---|---|

|

Department of Justice |

Providing a legislative and policy framework for and resourcing the justice system |

|

Police Service of Northern Ireland |

Investigating reported crimes, gathering evidence and identifying a person suspected of committing the offence |

|

Public Prosecution Service |

Deciding whether a suspect should be prosecuted for having committed an offence |

|

Northern Ireland Courts and Tribunals Service |

Managing the court estate and supporting the judiciary in its role of managing cases |

|

Youth Justice Agency |

Responsible for making communities safer by helping children stop offending through the delivery of a range of support services to young people within the community and within a custodial setting. |

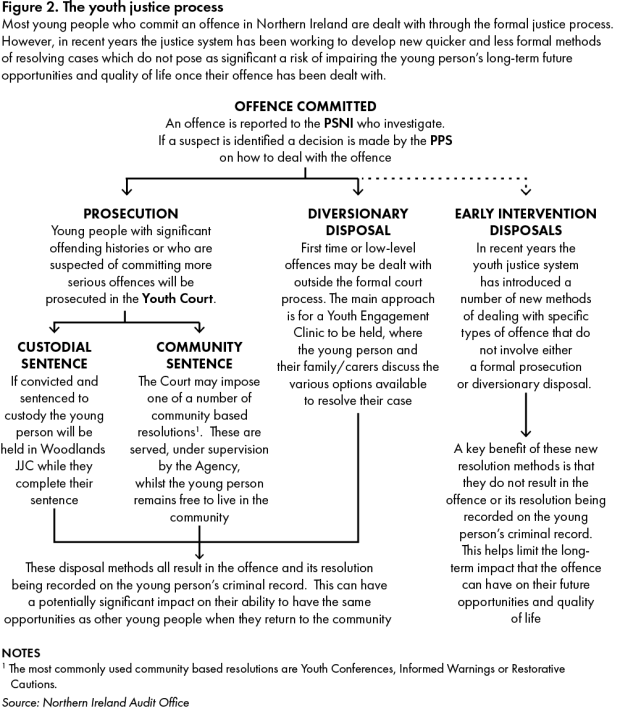

1.2 The justice system can deal with young people who commit an offence in a number of different ways (Figure 2). Young people who commit more serious offences, or who have histories of repeat offending, will be prosecuted in the youth court. First time and low level offenders can be dealt with through a number of different diversionary disposal methods which are available to allow for criminal incidents to be resolved in a proportionate and efficient way that avoids the need for a full court hearing.

1.3 Young people convicted in court may be subject to either a custodial or community based sentence. Any custodial sentence will be served in Woodlands Juvenile Justice Centre, under the care of staff from the Youth Justice Agency (the Agency) Custodial Services Directorate. Those receiving a community-based sentence will complete it under the supervision of staff from the Agency’s Youth Justice Services Directorate. Youth Justice Services are also responsible for working with those young people whose case is resolved through the use of a diversionary disposal.

The youth justice system is in the early stages of a major reform programme

1.4 In 2016, the youth justice system undertook an appraisal of how the system in Northern Ireland was working – the Scoping Study into Children in the Justice System. This review was initiated to examine whether the youth justice system was fit for purpose, and make recommendations that would enhance how the system worked to improve outcomes for young people who came into contact with it. The group responsible for undertaking the work engaged with a range of statutory and non-statutory organisations, and reported a general consensus that change was needed to improve the effectiveness of the system:

The fundamental question asked throughout the Scoping Study process, to policy makers, practitioners, the children, their families, victims’ representatives and the voluntary and community sector was: “What do we want to happen to children who have committed offences?” The response was clear: children and young people should be held accountable for their actions, but within a system which provides them with the interventions and support they need to change their behaviour and return to normal life.

The follow-up question was: “Does the youth justice system as currently configured allow this to happen?” The sheer scale of the proposals for necessary change put forward from the statutory organisations involved in the Scoping Study shows that it does not.

1.5 To make the system more effective, the Scoping Study argued that the justice system needed to move away from an operating model that treats children who offend as offenders first, to one that treats them as children first. In practice, this means recognising that their offending behaviours may potentially be only one of a number of issues they have. The justice system should facilitate and assist the young person to access appropriate support for other non-justice needs at the same time as dealing with the offence(s) they have committed. Doing this well would require the justice system and other key public services, for example health and education, to work together to have a positive impact on individual children.

1.6 The Department, Agency and other partners are in the early stages of implementing the reforms to address these issues, affecting various parts of the justice system.

In 2017 we published our review of the youth justice system

1.7 Shortly after the completion of the Scoping Study, we published Managing children who offend. This report focused primarily on the responsibilities of the Department of Justice and the Youth Justice Agency within the wider system, and identified three strategic issues:

- the need for a specific strategy to coordinate the delivery of youth justice services, policy and interventions;

- the need for better measurement and reporting on the impact that the services delivered by the Youth Justice Agency had on the young people it worked with; and

- the need to develop the capacity to identify and apportion the costs of different services delivered by the Agency.

Failing to address these issues could present a significant risk to implementing an effective transformation programme.

Scope and structure

1.8 In this report we follow up the progress made by the Department and the Agency since 2017. The structure of the report is:

- Part Two considers the major trends in youth justice since 2017; and

- Part Three provides an update on the key issues in our report.

Part Two: Evolving the youth justice system

Substantial reform of the youth justice system has been subject to delay

2.1 In March 2016 the Minister reported the proposals made in the Scoping Study to the Assembly, which fell across three themes:

- putting welfare at the heart of the justice system;

- maximising community involvement and increasing exit points from the justice system; and

- developing the disposal options available to the judiciary whilst also reducing the use of custody to make it truly a measure of last resort.

2.2 However, progress towards developing a programme of action was delayed first by changes in Ministerial priorities following an Assembly election in May 2016 and then the absence of a functioning Assembly between 2017 and 2019. In early 2019 the Department and Agency agreed a new strategic plan to implement the changes envisaged in the Scoping Study – Transitioning Youth Justice. The youth justice system is still in the early stages of implementing these reforms.

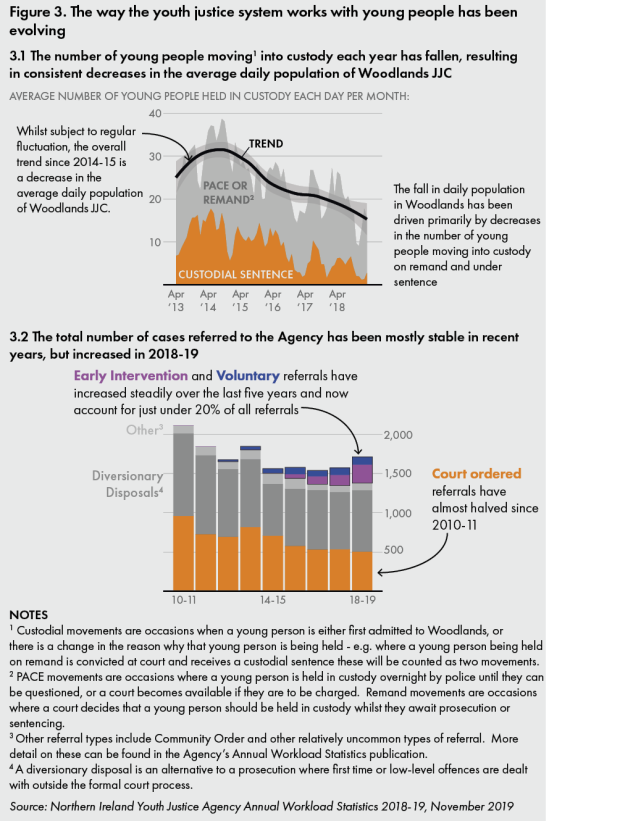

2.3 Despite the time taken to develop a formal transformation programme, in recent years the system has been attempting to evolve, as much as it can within existing legislative and operational constraints, to work in ways that are more consistent with the issues identified in the Scoping Study. One feature of this evolution has been the decreasing numbers of young people entering and being held in Woodlands JJC on remand or as a result of a custodial sentence. Within the Agency’s Youth Justice Services directorate, there has been a steady growth of Early Intervention initiatives which are dealing with a greater number of young people each year (Figure 3). More detail on how early intervention works in Northern Ireland, and on the specific initiatives that have been developed, is available at Appendix 1.

Reoffending rates have remained relatively stable

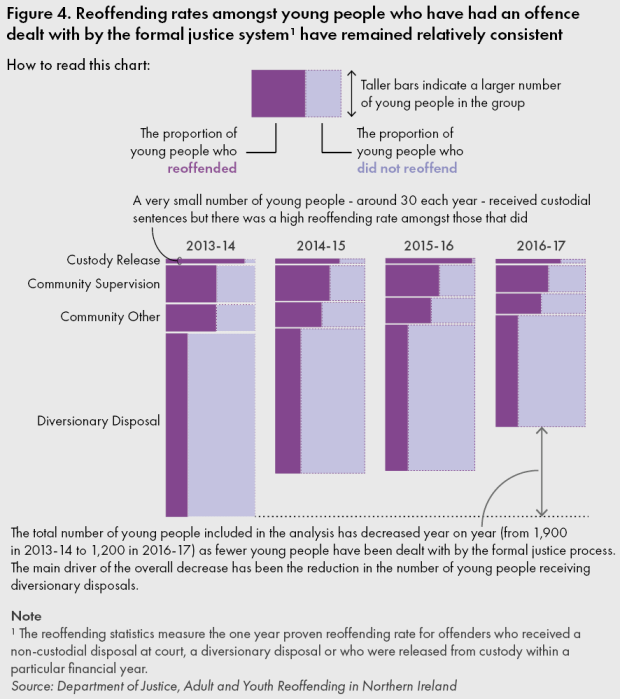

2.4 Due to the need to allow time for reoffending to occur and be proven, reoffending statistics lag behind other key performance statistics about the justice system. At the time of our previous report the most up to date analysis of reoffending rates amongst young people covered 2013-14. Since then, updates have been produced for 2014-15, 2015-16 and 2016-17.

2.5 These figures reflect a general decrease in the volume of young people being dealt with through the traditional formal justice process, but reoffending rates have remained generally stable year on year for those that are (Figure 4). In common with overall reoffending rates, other related significant trends have remained relatively consistent: those who do reoffend tend to do so relatively quickly after exiting the justice system, and a small proportion of prolific offenders go on to commit a significant number of further offences.

Delays in the justice process are detrimental to the young people involved

2.6 The speed with which crimes are investigated and dealt with is a key issue for the entire justice system. The quicker the process, the sooner victims can see that justice has been done and the sooner that those convicted can serve their sentence, begin rehabilitation and depart the system ready to reintegrate into the community without reoffending.

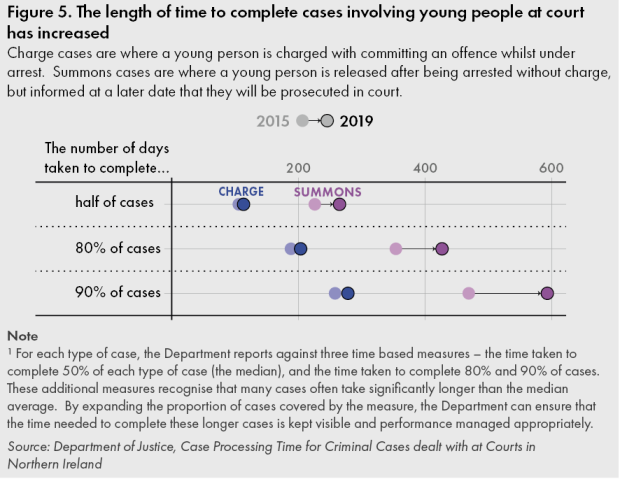

2.7 This is particularly important for children who offend. Quicker disposal allows for substantive rehabilitative work to commence sooner. Delays in the completion of a prosecution or diversionary disposal process mean that a young person can potentially commit many further offences before their original offence is dealt with. Where a young person falls into a cycle of repeated offending and multiple contacts with the justice system, this can have a hugely negative impact upon long-term life outcomes, health, wellbeing and welfare. It is therefore imperative that they are dealt with appropriately, provided with any support they need and exit the justice system as quickly as possible. Despite the decreasing volume of cases being processed at court, there has been no evidence of a significant improvement in timeliness and the most recent figures show generally deteriorating performance since 2014-15 – the first year that detailed measurements were compiled (Figure 5).

2.8 One of the benefits that diversionary disposals are believed to offer over court based disposals is that they are quicker. This can mitigate against the risks discussed above associated with long drawn out court processes. Whilst the Department has begun to publish an annual analysis of diversionary disposals which includes an assessment of the time they take, this does not cover the same period covered by the statistics used above. It is therefore not possible to assess the degree to which these are quicker than court processes. The Department told us that it is not possible to carry out this analysis.

The Agency’s funding has fallen significantly

2.9 There are a range of different organisations across the justice system who work with young people who offend. These include the Youth Justice Agency, the PSNI, the PPS, the NICTS, and the Department. The Agency works solely with young people and it is therefore straightforward to identify this component of the total cost of dealing with young people who offend. However, across the wider system there is no reliable measure or estimate of the costs incurred in other organisations.

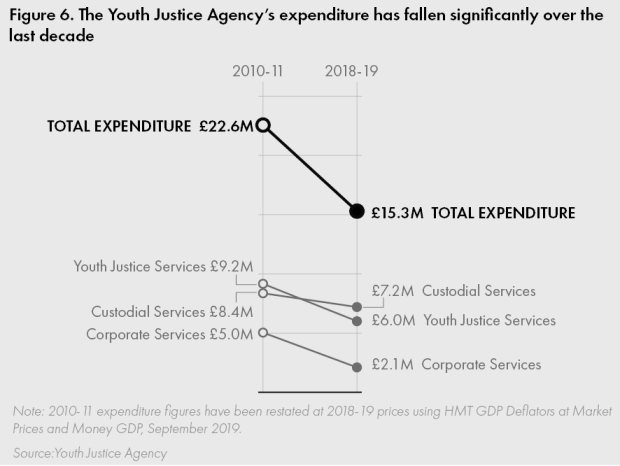

2.10 The Agency’s funding has been steadily decreasing since 2010-11, to the extent that it fell by a third in real terms to 2018-19 (Figure 6). Nevertheless, despite the sustained reduction in the number of young people entering and being held in custody, the Custodial Services Directorate has been subject to the lowest level of expenditure reductions over the decade. This is a consequence of a large proportion of costs of this facility being fixed in nature, and not driven by the volume of young people entering or held in the centre. The recognition of the increased under-utilisation of this significant resource has been one of the considerations contributing to ongoing work intended to repurpose the facility.

Children in custody often have the most significant care needs

2.11 Children in custody are held in Woodlands JJC. They can enter in three ways:

- when a young person is arrested, but unable to be brought before a court until the next working day, legislation requires that they should be held in a place of safety if they cannot be released on bail. Whilst a number of potential places of safety are identified, in practice young people in Northern Ireland are either held in Woodlands JJC or a police custody suite;

- if charged with a serious offence a young person may be held in Woodlands whilst they are prosecuted; or

- as a result of a custodial sentence in court.

2.12 It is generally accepted that those sent to Woodlands often have the most significant care needs and face the most adversity in their lives. An assessment carried out on 147 young people admitted during 2016 found that almost half were involved with mental health services and had a mental health diagnosis. The assessment also highlighted major educational deficits, including moderate to severe learning difficulties, lack of engagement with mainstream education and a significant number with Special Educational Needs Assessments. More than 75 per cent were not in any form of education or training. Despite the challenges these often severe levels of need present to staff, the level of care and support provided to young people in Woodlands has been recognised as being of a consistently high standard (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Inspections

Inspections have reported a high standard of care

May 2015 “Since opening in 2007, the JJC has significantly improved the child custody system in Northern Ireland. The design and fabric of the building, the progressive regime and the commitment of a large staff group all contributed to a providing a safe, secure and caring environment for the children committed to custody.”

June 2018 “This cyclical inspection of Woodlands JJC confirms that it remains the ‘jewel in the crown’ for the Department of Justice and is the envy of neighbouring jurisdictions.”

Source: CJINI

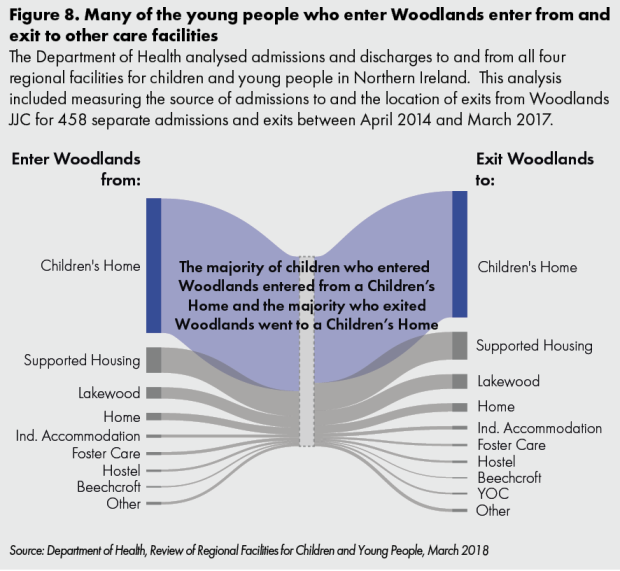

2.13 Given these levels of need, and the relatively short duration of children’s residence in Woodlands, there is only so much progress staff can make when working with young people. Many who enter custody are trapped in a “revolving door”, moving between health and social care facilities and Woodlands. A significant proportion of young people committed to custody come from and exit to the social care system (Figure 8). It has been difficult to sustain the level of support offered to children in Woodlands once they move into other care settings.

2.14 Transitioning Youth Justice included two major objectives in terms of changing how custody is used in the youth justice system:

- repurposing of Woodlands JJC away from being a solely justice-based facility; and

- ensuring that custody was only used as a last resort.

Part Three: Progress on key issues

Further work is required to fully implement our original recommendations and support an effective reform process

3.1 In our 2017 report we highlighted how the ability of the youth justice system to demonstrate it was achieving value for money hinged on its ability to measure, report and analyse the cost of the various activities that taxpayers were funding, and the benefits that resulted from those activities. Being able to measure, analyse and report such information is also essential to support the effective management of a reform programme.

3.2 We found that the arrangements in place to deliver these functions were not effective, and made recommendations intended to help improve those arrangements. In particular we identified three main strategic issues that needed to be addressed:

- the need for a specific strategy to coordinate the delivery of youth justice services, policy and interventions;

- the need for better measurement and reporting of the impact that the services delivered by the Agency had on the young people it worked with; and

- the need to develop the capacity to identify and apportion the costs of different services delivered by the Agency.

Since then the Department and the Agency have begun working towards addressing these issues, at the same time as reforming the way the youth justice system works, to better meet the needs of young people.

3.3 The Department and Agency have made progress towards implementing these recommendations over the last three years. However, the work to date does not fully meet the needs identified in our previous report. Without addressing these strategic issues, the Department and the Agency risk falling short on their ambitious agenda.

Transitioning Youth Justice presents a vision of how youth justice should work but is not a fully developed transformation strategy

3.4 The development of Transitioning Youth Justice represents the first step in designing a cross-Executive system for managing children who offend. The Department, Agency and other organisations have established shared principles that should dictate how operational practices should be structured. The youth justice system has sought to ensure that these principles emphasise the needs of service users. The operational changes proposed are consistent with the vision set out in Transitioning Youth Justice, and the earlier Scoping Study and Ministerial Statement.

3.5 However, these principles and the emerging strategy have not been supported by a robust and documented preliminary quantitative analysis of how the system works. In the context of reforming the youth justice system, there is a need to map fully and measure how the system is working, and to identify and quantify the impact of problems throughout the system. A good deal of the performance data necessary is already available within different parts of the youth justice system and we refer to it in this report, for example, custodial movements and delays in court. This information, brought together, should provide the basis for developing a prioritised, sequenced programme of work to change the system and deliver a better overall process.

3.6 At the time the Scoping Study was undertaken, the type of management information needed to support this type of exercise was not readily available. Instead, detailed analysis is being carried out on particular issues as and when they are being addressed. For example, work on the repurposing of Woodlands JJC is being developed with reference to a detailed review carried out during in 2018. This review included detailed analysis of how the network of secure care facilities for young people in Northern Ireland worked, and the issues that young people who came within that network encountered. The paper which emerged from this review is a good example of the type of exercise we would have expected to initiate the reform programme and support long-term planning for reform.

3.7 Other than the completion of the repurposing of Woodlands JJC by 2022, there is currently no clearly defined end-state design for how the entire youth justice system will work. The Agency told us that instead, the youth justice system would strive to constantly improve how it works with young people, based on the application of evolving research and best practice and in line with the principles set out in Transitioning Youth Justice. Detailed project plans, which included specific objectives and timescales, would be established when necessary in respect of individual activities, such as the repurposing of Woodlands.

3.8 Given the broad high level objectives of Transitioning Youth Justice, there is a risk this approach will make it difficult to measure and report the full impact of the programme across the entire system and the benefits that are derived as the programme unfolds.

3.9 During our fieldwork we were told that the success of the reform programme would be measured primarily in terms of changes in the volume of young people coming into contact with the justice system each year. For those children that do come into contact with the system, the ability of the Agency to support more positive outcomes for them is to be measured using a newly developed Outcomes Based Accountability-based performance management system. However, the new performance system is not yet developed sufficiently to provide this level of information.

Recommendation 1

The vision outlined in Transitioning Youth Justice should be developed further into a comprehensive strategy. This would:

- provide clarity to stakeholders on the evidence base that supports the proposed reforms;

- define the benefits that will be achieved from successful change; and

- establish a framework for monitoring success.

Measuring and reporting the impact that the work of the youth justice system has on the young people it deals with remains a challenge

3.10 As part of its Programme for Government (PfG), the Northern Ireland Executive has developed a new system for designing and delivering public services based on the principles of Outcomes Based Accountability (Figure 9). Under this system all public organisations should be able to demonstrate the impact that the services they deliver have upon those who receive them, and thus show the benefits that those services bring to citizens.

Figure 9. Outcomes Based Accountability

In 2014 the Northern Ireland Executive asked the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to assess its public sector reform agenda. A key recommendation in the resulting report produced by the OECD was that the Executive should “prepare and implement a multi-year strategy, outcomes based Programme for Government”.

Following this recommendation a multi-year PfG was developed, comprising 12 desired outcomes of overall societal well-being that public organisations should work to achieve. Each year an Annual Delivery Plan is produced which details specific actions which will be undertaken by organisations to work towards realising these outcomes.

Under these long and shorter term frameworks there are two systems of accountability. In order to measure long-term progress towards the realisation of the PfG’s outcomes, a number of population accountability indicators are used to validate whether the actions of public organisations are having an impact. Improving performance as measured by a particular indicator will often require a number of different public organisations to work in collaboration to ensure that services between different departments are coordinated and joined up.

The resources that organisations use to deliver services are provided each year by the Assembly. The management of these organisations are responsible for ensuring that these resources are used on activities that will support the objectives of the PfG. It is essential that they monitor and report to key stakeholders – the Assembly and the taxpayer - how they have used the resources granted to them, and the resulting impact on client populations. Under the OBA framework, this is known as performance accountability, and requires that organisations are able to measure different programmes or services they deliver against three main questions:

- How much did we do?

- How well did we do it?

- Is anyone better off as a result?

For more information on OBA, see our best practice guide: Performance Management for Outcomes

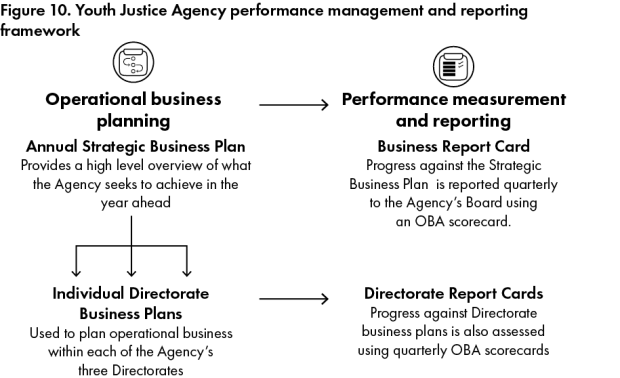

3.11 In 2017 the performance measurement and reporting systems used by the Agency were characterised by the use of numerous measures describing activities and achievements, but with little reference to the outcome of that activity for those served. Since then, the Agency has worked to implement a new system of performance management and reporting based on the principles of OBA (Figure 10). We used one of the Agency’s scorecards as an example of good practice in our good practice guide, published in 2019.

3.12 Nevertheless, there is more to do. Measuring, reporting and analysing the impact that various activities have on service users is essential for both accountability and effective long-term governance of the youth justice system and its reform. While senior management can readily articulate examples of progress, performance measurement does not yet provide a clear and comprehensive understanding of the impact of the Agency’s work on the lives and offending behaviour of the young people it deals with. Often, measures included with the intention of reporting impact were more appropriate as measures of quality: for example, results of satisfaction surveys from young people and their families. In some cases, appropriate measures or indicators have yet to be developed. It is important that work towards the development of a fully realised OBA-based performance management system is sustained.

3.13 One of the challenges that the Agency faces in gathering the management information needed to support effective performance reporting is the lack of a dedicated case management system. In 2017 information about programmes delivered to young people was not held in a format that facilitated summary analysis. Records were also often incomplete.

3.14 The Agency has now established new arrangements to improve record keeping. While the quality of these processes is undoubtedly better, these arrangements are a work-around in the absence of a case management system. The Agency recognises that they are no substitute for such a system, which would be more likely to provide efficient support for a sophisticated and flexible performance measurement and reporting regime.

Recommendation 2

The Agency should continue to develop its performance reporting regime with greater focus on the impact of its work with children and families, in line with the principles of OBA.

There continues to be insufficient understanding of costs throughout the youth justice system

3.15 In 2017 the organisations within the youth justice system lacked the capacity to identify and apportion the cost of the different services they provided. Consequently, the system as a whole could not measure the total cost of youth justice. Little progress has been made towards addressing either of these issues.

3.16 Across the youth justice system, there remains a view that any attempt to disaggregate costs relating to youth justice from other costs of those agencies who deal with both adults and children is difficult and in itself, likely to be cost prohibitive. The Agency has made no substantive progress in improving the quality of information available about the unit cost of the different services it delivers.

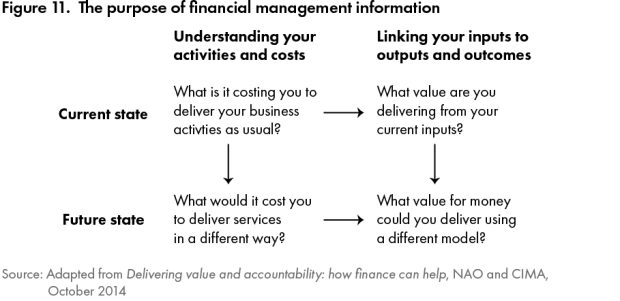

3.17 The absence of detailed financial information is a significant omission in both the Agency’s performance management system and in the documentation relating to the transformation programme that we reviewed. An effective financial management system should be able to readily provide detailed information that supports both effective performance reporting and change management (Figure 11). As part of an OBA-based system, understanding the resource cost of particular activities is an essential component of the how much did we do measure. The absence of costing information makes it impossible to understand the resource cost of the activity being reported on.

3.18 Inadequate financial data also poses a risk to the planning and management of reform. The provision or use of detailed financial information has not been evident so far in the development of strategies and transformation plans. There remains little evidence of the full financial impact of planned changes even in those parts of the reform programme that are furthest developed.

3.19 For example, one of the most developed strands of work is the repurposing of Woodlands JJC. In early 2019, the Departments of Health and Justice established a Programme Board to develop plans for the implementation of a new joint health and justice facility on the existing Woodlands. In January 2020, the Ministers of Health and Justice approved a design model outlining how the new facility would work, and how it would connect with community based services. At the same time, staff were working on preparing a public consultation exercise based on this model, which was delayed due to the Coronavirus outbreak. We were told that the Programme Board is still working towards a project completion date of March 2022.

3.20 There is currently no robust financial analysis of the cost of the proposed model. We were told that the Programme Board had intended from the outset that the new facility would be, as far as practicable, cost –neutral relative to the cost of current service provision. Whilst there had been some preliminary analysis of costs, there is no detailed analysis of the current cost of all the activities that will be subsumed in the new arrangements, nor the estimated cost of the future service model.

3.21 We were also told that the forthcoming consultation exercise is intended to help provide solutions to important issues where the final detail of how the new facility will work remains uncertain. They include questions about how the joint campus will fit within existing departmental boundaries and where ownership will lie, what the appropriate level of staffing will be (in terms of training, skills mix and support staff), and the cost of the new service model. It is likely that these issues will have cost implications which have not been explored fully so far.

Recommendation 3

The youth justice system should work together to further develop its financial management information in order to better understand the costs of whole-system activities and to link resource inputs to outputs and outcomes.

Appendix 1: Early Intervention

Overview of early intervention

Early intervention in youth justice is focused on two groups of young people. The first group are young people who have committed a single low level offence and have no significant related health or social issues. Often these young people, and the wider community, are served best by a quick justice process that exits or diverts them from the formal process as quickly as possible. Doing this successfully means that justice can be dispensed as efficiently as possible in terms of time and cost and that potential long-term impacts on the young person’s life outcomes are minimised.

The other, smaller group are those young people who have begun to offend and are identified as having complex needs that, without considerable support and intervention, may contribute to the risk of a cycle of repeat offending and prolonged involvement with the justice system.

For these young people, sustained interaction with the justice system can itself be a barrier to improving their likely long-term life outcomes and impose an increased risk to reoffending in the future. Factors such as being labelled a criminal, a negative reputation amongst their family and community and having a criminal record can in themselves be further barriers to the young person reintegrating into the community and desisting from offending behaviour.

Often it is only through contact with the Youth Justice Agency that these young people and their families are directed to appropriate statutory and voluntary services that can help them deal with the issues they face. In such cases, early intervention is about being able to identify young people with needs at an earlier stage of their offending behaviour than currently being achieved, and delivering or directing them towards support and interventions to help address these issues to mitigate the risk of repeat offending.

Operationally, this has been implemented through the incremental growth of specific schemes introducing early intervention principles into discrete areas of work.

Growth of early intervention initiatives

|

Early Stage Intervention |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Early Intervention Transformation Funding |

In 2015, the YJA secured extraordinary funding of around £150,000 per year for three years from the Early Intervention Transformation Programme to help initiate new early intervention work with its service users. This money was used in two ways:

Since external funding for this project elapsed in 2017-18, the Agency has continued to maintain the services that were provided, meeting the costs through its regular annual funding allocation. |

|

Community Resolution Notice Referral Schemes |

Community Resolution Notices are a means of dealing with minor offences by allowing PSNI officers at the scene to facilitate an agreement between the victim of the offence and the offender as to how the offender can make good on the harm caused to the victim without incurring a criminal record. This avoids the need for a lengthy formal justice process to resolve the incident. In March 2018, the YJA commenced a pilot in its Belfast and Southern areas whereby young people receiving a CRN could, where their offence was related to alcohol or drugs use and deemed appropriate, be offered the chance to participate voluntarily in a drug and alcohol awareness programme. In November 2018 this pilot was extended to cover drugs and alcohol related offences across the whole of Northern Ireland. Between February and July 2019 a further pilot, testing the effectiveness and capacity of the YJA to deliver such referrals across all other types of offence within the Belfast and Southern areas, was completed. Following evaluation of the results of this, it was decided that the approach should be applied to cover all offences across all of Northern Ireland from November 2019. |

|

Sexting Referral Scheme |

Since November 2019, the YJA and the PSNI have been piloting a Sexting Referral Scheme in the Belfast and Southern regions. This scheme allows for PSNI Youth Diversion Officers to refer children involved in minor “sexting” type offences to an awareness programme delivered by YJA staff, intended to reduce their likelihood of becoming involved in similar incidents in the future. |

|

Child Diversion Forum |

The Child Diversion Forum is a new multi-agency initiative that it is hoped will contribute to continued lower numbers of young people entering the formal justice system over time. The group will be made up of staff from the YJA, the PSNI, social services and Education Welfare Service. They will receive referrals about young people, primarily from the PSNI, who are on the cusp of being involved or have been involved in low level offending but have not yet become involved with the formal justice system – either through having been subject to a diversionary disposal or a court order. The Forum will share information about children who are referred with partner organisations and make decisions about any interventions/support that may be useful in helping reduce their risk of (re)offending. It is currently intended that a pilot exercise will run in early 2020, with a view to potential large scale roll-out across Northern Ireland sometime in late 2020. |