List of Abbreviations

CAMEO Customer Access to Maps Electronic Online

CAP Common Agricultural Policy

BT British Telecommunications Group plc

DAERA Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

DE Department of Education

DCAL Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure

DEL Department for Employment and Learning

DfC Department for Communities

DfE Department for the Economy

DfI Department for Infrastructure

DoE Department of the Environment

DoF Department of Finance

DoJ Department of Justice

DRD Department for Regional Development

DSS Digital Shared Services

DTP Digital Transformation Programme

DVLA Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (UK)

DVA Driver and Vehicle Agency

ESS Enterprise Shared Services

GDS Government Digital Service

GeNI Genealogy Project for Northern Ireland

GP General Practitioner

GRONI General Register Office Northern Ireland

HSC Health and Social Care

ICT Information and Communications Technology

HMRC Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs

IA Internal Audit

LPS Land and Property Services

NHS National Health Service

NIAO Northern Ireland Audit Office

NICS Northern Ireland Civil Service

NIDA Northern Ireland Identity Assurance

NIROS Northern Ireland Registration Office System

NAO National Audit Office

NI Northern Ireland

PAC Public Accounts Committee

PACWAC Planning Appeals Commission/Water Appeals Commission

PfG Programme for Government

PPE Post Project Evaluation

PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland

OSNI Ordnance Survey Northern Ireland

SSA Social Security Agency

TEO The Executive Office

UK United Kingdom

Key Facts

Timeline of Digital Transformation Strategic Partner Project

2008

NI Direct (Phase 1)

£5.7 million contract with Steria Limited to demonstrate and quantify the benefits of a single contact centre

2012

NI Direct (Phase 1)

Final expenditure incurred – £6.5 million

NI Direct (Phase 2) Strategic Partner Project

£50 million contract with British Telecommunications (BT) plc to extend the use of the contact centre and procure expertise to develop online services

2014

Digital Transformation Programme commenced in April 2014

2017

NI Direct (Phase 2) Strategic Partner Project

Predicted expenditure to October 2019 – £70 million

2018

NI Direct (Phase 2) Strategic Partner Project

Actual expenditure to 31 March 2018 – £62 million

Predicted expenditure to October 2019 – £77 million

2019

NI Direct (Phase 2) Strategic Partner Project

Extended to October 2022

2022

NI Direct (Phase 2) Strategic Partner Project

Predicted expenditure to October 2022 – £110 million – more than twice the original contract

Executive Summary

1. In 2008, the NI Direct Phase 1 contract (£6.5 million) transformed the Northern Ireland Customer Interaction Centre from an exclusively switchboard service into a modern customer contact centre providing information and simple transactional services on behalf of various public sector service providers.

2. The NI Direct Phase 2 contract, a £50 million Strategic Partner Project with British Telecommunications plc (BT) let in 2012, facilitated extending use of the contact centre across the broader public sector, the consolidation of central government (and Arm’s Length Bodies) websites through nidirect.gov.uk and provided a route to procurement for departments developing or refreshing programmes involving online or telephone interaction.

3. In September 2012, all departments were notified that, when developing or refreshing programmes involving online or telephone interaction, there should be a presumption in favour of using the Strategic Partner Project unless the approved business case determined an alternative option.

4. Responsibility for managing individual projects procured through the Strategic Partner Project contract fell to individual departments. The Department of Finance (DoF) was responsible for overall management of this contract – reviewing and challenging BT costs. Despite criticisms from internal audit and external consultants, DoF failed to put sufficiently strong financial controls in place to manage the Strategic Partner Project until 2018, six years after the start of the contract.

5. It is unacceptable that spend was not more closely monitored, tracked and controlled and that, prior to September 2018, DoF was not in a position to supply details of total costs by individual project. As a result of the inclusion of additional projects and individual project cost overruns (due to project add‐ons and extensions), DoF now estimates that total spend through the Strategic Partner Project will be in the region of £110 million – more than twice the original contract value of £50 million.

6. DoF, with overall responsibility for managing the Strategic Partner Project, should have had stronger controls in place to monitor and control spend through the Strategic Partner Project on individual projects. We welcome the “deep-dive” review undertaken by the Department’s Audit and Risk Assurance Committee in October 2018 which explored the financial and contractual position with the Strategic Partner Project. Following that review, the Accounting Officer approved a three-year contract extension (to October 2022) and approved the revised cost estimate of £110 million.

7. Despite the contract value of £50 million on the Strategic Partner Project, projects identified for procurement through the Strategic Partner Project related primarily to central government services rather than those public services which are most valued by the public (for example, health services). The rationale was unclear for procuring several early projects through the Strategic Partner Project which involved replacing out-of-date legacy systems; were relevant to limited users; or offered little citizen interaction. The absence of collaborative working across government departments and public sector bodies has hindered the implementation of transformational, citizen‐centred projects.

8. Digital transformation has the potential to significantly reduce costs. It is disappointing that business cases supporting early projects procured through the Strategic Partner Project, made no mention of the expected level of savings while only four (of a total of 12) projects reported that savings had been made. DoF (as contract manager) should have been proactive in collating and validating savings information from departments.

Scope of this Report

9. This report examines the extent to which expenditure under the optional services element of the NI Direct Strategic Partner Project (originally estimated to cost £30 million) was well managed, achieved value for money and was successful in achieving channel shift and moving citizen services online:

- Part 1 sets out the background to the area and outlines the costs incurred through the NI Direct Strategic Partner Project;

- Part 2 examines the adequacy of arrangements in place for managing the contract with BT;

- Part 3 considers the arrangements for selecting and prioritising projects for inclusion in the Strategic Partner Project; and

- Part 4 examines the benefits derived through use of the Strategic Partner Project.

Report Methodology

10. In order to complete this report we:

- Issued a questionnaire to each department asking for a range of information in relation to each digital transformation project;

- Reviewed various documentation provided by departments and DoF;

- Undertook interviews with relevant staff within departments;

- Considered the work of DoF’s Internal Audit and other relevant reports; and

- Took steps to confirm the total value of financial transactions under the contract with BT.

Value for Money Conclusion

11. In our opinion, it is not possible to conclude that digital transformation to date through the Strategic Partner Project has delivered value for money for citizens across Northern Ireland.

12. In more general terms, we acknowledge that progress has been made on Northern Ireland’s journey to the digital transformation of public services. DoF accepts that there is a long way to go before Northern Ireland public services are fully citizen-centred and transformed. Its current digital strategies focus on leveraging innovative technologies to improve public service provision. DoF explains that its initial approach was to concentrate on central government services to demonstrate the benefits of transformation and then develop the journey into wider public service areas. By starting small and building on success to deliver the best outcomes, its ambition has been to embed culture change across public service providers. DoF recognises the importance of developing public sector staff to build capacity and capability and address the existing reliance on the private sector.

Summary of Key Points

13. In 2012, DoF appointed British Telecommunication Group plc (BT) as its Strategic Partner to deliver Phase 2 of NI Direct (the Strategic Partner Project) which involved extending use of the contact centre across the broader public sector and procuring expertise (Information Technology solutions, skills and capabilities) to support Northern Ireland public bodies develop online services.

14. The Strategic Partner Project commenced on October 2012 for a period of 84 months (to October 2019) with an option to extend for three years (to October 2022). Funding was to be maintained within £50 million. Departments and agencies developing or redesigning services, were to ensure that digital online services became the primary means of interacting with citizens, to provide access to online services through the NI Direct portal and were mandated to favour procurement through the Strategic Partner Project (except where an approved business case determined an alternative).

15. By 2017, predicted expenditure (to September 2019) totalled £70 million (40 per cent in excess of the original contract value (£50 million)). Following legal advice, the contract value was increased to £70 million; no further projects were approved for funding under the contract. By October 2018, it transpired that actual expenditure through the Strategic Partner Project over the period to October 2019 was likely to be in region of £77 million (as opposed to the predicted £70 million). In addition, DoF needed to extend the contract for the additional three year period (to October 2022) since alternative mechanisms for service provision had not been put in place. DoF estimates that expenditure to October 2022 will reach £110 million – more than twice the original contract value.

16. DoF’s failure to put effective financial controls in place to manage the contract was identified in several reviews of the Strategic Partner Project:

- In 2016, DoF’s Internal Audit (IA) provided a limited audit opinion on control management arrangements surrounding the Strategic Partner Project. IA was critical that DoF had overcommitted expenditure, could not provide details of actual spend against the contract and was not actively managing the contract, and had not received (or reviewed) BT annual audited project accounts.

- In 2017, external consultants concluded that, since costs through the Strategic Partner Project across each component were within the market range and below the market average, value for money had been achieved. However, the consultants were critical of the lack of project prioritisation, issues which impacted on the realisation of anticipated benefits and of the limited contract management arrangements within DoF.

- In our audit of the 2016-17 DoF Financial Statements, we highlighted that the capital costs associated with the Strategic Partner Project exceeded the amount in the original business case by almost £2 million. We also noted that the latest estimates of total costs under the £50 million contract were likely to be in the region of £80 million. We recommended that DoF develop more robust mechanisms to monitor the expenditure on contracts. In our 2017-18 audit, we noted that despite the significant time already spent developing an improved monitoring system, DoF was unable to fully attribute all costs under the Strategic Partner Project to individual projects.

17. Despite these criticisms, DoF was not in a position to provide us with a breakdown of costs by project until September 2018.

18. By 31 March 2018, actual expenditure of £62 million had been incurred against the £50 million in the Strategic Partner Project. Most of the expenditure related to 13 major development and application solutions (including one project which is not yet completed), two major consultancy projects and a suite of cross-cutting, reusable applications available across the public sector. Costs relating to three of the 12 completed digital development projects and two major consultancy projects exceeded estimates contained in the original business cases while five digital development projects experienced delivery delays. This is indicative of poor project specification and monitoring by individual departments (associated with the traditional (rather than agile) delivery model). In addition, in our view, as contract owners, DoF should have been much more involved in ensuring costs were controlled.

19. A Gateway review produced in January 2016 identified that “there [were] causes to question whether the contract as written continues to fit with the business being conducted” and concluded that “… there [was] growing evidence that the contract, as let, may have outlived its usefulness and the [Northern Ireland Civil Service] … might be better served by a more agile approach”. The review team was also critical of the lack of transparency by the Strategic Partner and of the extent to which DoF was aware of whether it was entitled to gain share settlements for any of the years since commencement of the contract. It identified that “innovation received from the Strategic Partner was ’patchy’ with the bulk of innovation coming either from the subcontractors or from within the Northern Ireland Civil Service”.

20. With an original contract value of £50 million (including £20 million relating to the costs of the contact centre), it was inevitable that all Northern Ireland public sector services could not be digitally transformed through the Strategic Partner Project. We were surprised that projects in the health, local government, welfare and policing sectors were not prioritised and moved forward through this or any other procurement route. Further, the rationale for procuring several projects through the Strategic Partner Project was unclear. For example, early procured projects included:

- Upgrades and replacement of out-of-date (or contract) legacy systems rather than transformational projects;

- A number of services which have limited users; and

- Services providing little interaction with citizens.

21. To be effective in developing citizen-centred service solutions, public bodies need to break down organisational barriers, share information and work together to provide a seamless, ‘joined-up’ service. In terms of projects procured through the Strategic Partner Project, there was little evidence of public bodies working together, or with their counterparts in Great Britain, to identify innovative, transformational citizen-centred projects. DoF acknowledges this but highlighted that it has engaged with the Government Digital Service in Whitehall and various other Great Britain government departments.

22. While business cases were produced for each of the 12 completed major development and application solutions, a number of individual departmental business cases made no mention of the potential to generate financial savings. Only four of the 12 completed projects reported that savings had been generated. DoF (using an average cost per transaction) claims that savings of £99 million have been generated as a result of the move to online services. However, this is a notional figure. DoF does not undertake any work to collate (and verify) actual savings generated. DoF pointed out that offering online access has allowed public service providers to maintain services despite suffering staff losses through voluntary exit schemes.

23. Post project evaluations (PPEs) are useful in assessing the success of projects by comparing actual costs and benefits against estimates. While we note that the Construction and Procurement Delivery unit within DoF routinely collates all PPEs and circulates information on key learning points, we would have expected that the contract owners (NI Direct/ Digital Transformation Programme team) would also have reviewed PPEs specific to the Strategic Partner Project to ensure lessons were learned not just in DoF but across the wider public sector. Completed post project evaluations highlighted that projects progressed in the early stages of the Strategic Partner Project experienced some teething problems, mainly in relation to governance arrangements, confusion over the individual project requirements and a lack of cohesion between suppliers.

Summary of Recommendations

- Lessons must be learned for any future contracts. We recommend that all departments ensure that strong financial management controls are in place to ensure that appropriate monitoring of expenditure is embedded in management processes. To ensure this, departments managing contracts must ensure that sufficient expert resources (for example, financial management staff) are retained throughout the duration of the contract.

- Where individual contracts are used by several departments, we recommend that a central record of key financial data is maintained by the contract owner.

- DoF must consider how digital transformation can be advanced across the entire public sector. In order to maximise the benefits for citizens, services must work seamlessly across existing organisational barriers.

- We acknowledge the role of individual departments in completing PPEs to assess and learn from the success or otherwise of individual projects. We recommend that, for future contracts, the contract owners ensure that they are fully sighted on all PPEs so that they can ensure that key lessons are learned. We recommend that DoF creates a central register of lessons learned and makes this easily accessible to all public bodies embarking on transformation projects.

- While we acknowledge that much good practice guidance on contract and project management exists across the public sector, we recommend that DoF develops a short guide to assist those progressing digital transformation projects. In our view, this would help ensure adherence to best practice.

- We recommend that DoF undertakes a review of transformation activities across the Northern Ireland public sector and uses the results to ensure that future transformation is taken forward in a strategic and co-ordinated way.

- We recommend that DoF mandates that best possible re-use is made of code, components, tools, applications and data across central government to avoid duplication of effort. NI Direct should be the single portal for all digital government services. DoF should also explore opportunities for development across the local government sector.

- Given that citizens want a “tell me once approach” to services and verification, we recommend that DoF progresses work on the Mydirect portal at pace. This involves considering the concept of citizen identification and verification, exploring the option of a single identifier and exploiting use of inter-connected registers so that users do not have to re-submit data. In addition, DoF should continue to pursue opportunities for new technologies (such as Artificial Intelligence and Robotic Process Automation) for future digital transformation.

- DoF has benefited from working with the Government Digital Service in Whitehall and Estonia in relation to digital transformation. We therefore recommend that it considers creating a new partnership with a progressive government leading the way on digital transformation as an opportunity to learn and develop best practice and strategic analysis.

- We recommend that, in line with best practice, departments ensure that all business cases provide clear and robust baselines in terms of staff and resource costs along with realisation savings targets. This involves disclosing the unit cost of the existing provision so that actual savings realised can be calculated accurately.

Part One: Background and Introduction

The majority of Northern Ireland citizens frequently use the internet

1.1 The digital revolution is transforming the way we live. Recent research indicates that internet use across the United Kingdom (UK) is high and is rising. The increase seems set to continue with the rise in popularity of smartphones and tablets and the wide availability of fast internet connectivity. Virtually all UK adults aged 16 to 34 years (99 per cent) regularly use the internet. Internet use in the 65 to 74 age group increased to 80 per cent in 2018 (compared to 52 per cent in 2011). By 2018, the number of recent internet users aged 75 years and over had increased to 44 per cent (compared to 20 per cent in 2011). In overall terms, internet use in Northern Ireland (86 per cent) is marginally lower than other UK regions (90 per cent) but the gap is reducing.

1.2 Digital technology is increasingly becoming the default method for viewing information, streaming entertainment, shopping and interacting socially. As people make increasing use of digital technology, they expect public services to be available online so that they can access information and do business with government 24 hours a day. Individuals expect the same good quality, safe online experience from government as they do from online retailers and private sector businesses.

1.3 Continuing to provide government services exclusively through traditional channels (i.e. face-to- face, by telephone and mail) is no longer acceptable. It incurs additional costs, often provides a poor citizen experience and can create inefficiencies and delays. By identifying more innovative, efficient and smarter service provision, public bodies can improve the customer experience and generate savings.

1.4 Citizens needs do not always align with the complex organisational structures and boundaries of government. As a result, transformed services will increasingly need to span departments and public bodies. By developing efficient shared services and increasing collaboration, the public sector has the opportunity to release significant financial savings. The cost of an online transaction is thought to be in the region of 5 per cent of the cost of a face-to-face transaction. The Northern Ireland Executive is committed to ensuring that 70 per cent of all citizen transactions with government services are delivered using an online channel by 2019. The Department of Finance (DoF) confirmed that, at January 2019, 74 per cent of transactions were delivered online.

In 2018, the European Commission reported that Denmark, Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands have the most advanced digital economies in the European Union followed by Luxembourg, Estonia, the United Kingdom and Ireland

1.5 The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) is a composite index produced by the European Commission (the Commission) which summarises relevant indicators on Europe’s digital performance and tracks the progress of EU Member States in digital competitiveness.

1.6 In its 2018 publication, the Commission identified that Denmark, Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands have the most advanced digital economies in the European Union followed by Luxembourg, Estonia, the United Kingdom and Ireland. Romania, Greece, Bulgaria and Italy had the lowest scores on the index.

1.7 DESI reported that in Estonia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Lithuania, more than 80 per cent of internet users who need to submit forms to the public administration choose to do so through governmental portals. In the United Kingdom the percentage was slightly less than 80 per cent. Percentages in Italy, the Czech Republic, Greece and Germany were below 40 per cent.

1.8 Online service completion measures the extent to which administrative steps relating to major life events can be done online. Malta, Portugal, Estonia, Austria, Lithuania, Denmark, Spain and Finland were the best performing countries (scoring 90 points out of 100). The United Kingdom scored just under 80 points out 100. Romania had the lowest score with less than 60 points out of 100.

1.9 Inter-connected registers ensure that users do not have to re-submit data. DESI identified that their use is not yet widespread. While pre-filled forms are available, in the majority of Member States, the amount of data available in public services’ online forms was judged as “not satisfactory”. DESI reported that Member States are working towards improving the provision of pre-filled forms, noting a small increase compared to 2016, with Malta, Estonia, Finland and Latvia leading.

1.10 In the 12 months prior to the survey, only 18 per cent of EU citizens accessed health and care services online without having to go to a hospital or a doctor’s surgery (for example, by getting a prescription or a consultation online). Finland and Estonia had the higher usage of eHealth services (at just under 40 per cent). The percentage in the UK was around 25 per cent.

In 2015 DoF established a Concordat with Estonia given that it was considered to be among the most digitally advanced countries in the world

1.11 In 2015, the results of a global survey revealed that while there is a wide spectrum of digital maturity across public sector bodies worldwide, there are a common set of issues and barriers which hamper change – culture, procurement, workforce, leadership and strategy. The survey concluded that successful public bodies tend to be flexible and can adapt to the “one constant of the new digital age – change itself”.

1.12 Estonia is considered to be among the most digitally advanced countries in the world. Given that it has a small population of only 1.3 million (less than Northern Ireland at 1.8 million) spread over an area more than three times the size of Northern Ireland, the most cost-effective approach to reaching all citizens is to provide services online. Almost all (99.97 per cent) interactions between the Estonia government and citizens are now digital. A 2018 article explained how digital developments in Estonia have brought benefits for citizens and improved security across healthcare, education, voting, law enforcement and many other areas.

1.13 Estonia’s success is attributed to the introduction of a single citizen identity card and a strong trust between private sector companies, citizens and government which ensures transparency, allows dataset combination and enables systems to be connected. This approach allows the government, in real time, to monitor how industries are performing, to compare the success of specific regions and to explore expenditure trends. Citizens are asked only once for information – data exchange is pursued across Ministries. Given its success, DoF established a Concordat with Estonia in 2015.

1.14 Even UK systems considered to be digitally advanced fall short of arrangements in Estonia. In the UK, the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) tax portal for completing tax returns is considered to be successful. Estonia has taken arrangements a step further so that the citizen can authorise the bank to share financial data with the government which then completes the return on behalf of the citizen. Estonian schools must use a platform which connects students, teachers and parents. Parents (using an app) can monitor their child’s performance in real time becoming more engaged with their child’s development. Other successes within Estonia include thee-Residency scheme and the electronic voting system.

Digital transformation has the potential to join up government agencies and provide citizen access to services through a single portal

1.15 Across the UK public sector, the journey to digital transformation has begun. Digital self-services introduced by HMRC and the Driver and Vehicle Licence Agency (DVLA) are probably the best known examples. At the end of the journey, the public expects a joined-up digital experience across all government agencies, accessed through a single portal, which encompasses all aspects of the citizen’s life, from tax to healthcare to local government services. Over time, the number of website interactions should be reducing (rather than increasing) as unnecessary contact with government is reduced. A consolidation of Northern Ireland Government websites was completed in 2016. All Northern Ireland central government services (including ALBs) can now be accessed through nidirect.gov.uk. This substantially reduced the number of websites and simplified the citizen experience.

While UK citizens recognise that the public sector is increasing the number of digital services available and simplifying digital tools, many worry about the security of information provided

1.16 A report published in 2017 highlighted the results of a survey of 4,000 citizens across four countries (UK, France, Germany and Norway). Over half (58 per cent) believed that providing digital access has had a positive impact on the quality of public services. Over three-quarters (80 per cent) recognised that the public sector has increased the number of digital services available and two-thirds (66 per cent) considered that digital tools and services are increasingly easy to use. Taxation was judged the most advanced online public service.

1.17 Three quarters of UK citizens interviewed said it was a priority for government to provide more digital public services in the future. Health was judged as the most important UK public service to digitise.

1.18 UK citizen frustrations with existing government systems include the need to provide the same information several times (40 per cent), the complication of systems (35 per cent) and problems identifying the correct website to commence queries (24 per cent). Almost half of UK citizens (48 per cent) were worried that others may be able to access their online information and only 4 per cent of citizens considered that government has both the will and capacity to digitally transform services.

1.19 DoF told us that it’s Cyber Security: A Strategic Framework for Action addresses the issue of information trust and security with a Cyber Leadership Board taking the lead on three themes, Defend, Deter and Develop for the wider public sector.

An independent report published in 2016 identified the need for more innovation to enhance the “citizen-centeredness” of service design and delivery in Northern Ireland

1.20 A report published in 2016 highlighted that Northern Ireland was “well positioned to take advantage of the opportunities created by digital and innovative service delivery”. While recognising the work going on across the public sector, the report highlighted the need to “ensure that online services are developed with a ‘digital by design’ mind-set, not merely adding a layer of ‘digital paint’ on top of existing processes”.

1.21 The report identified that, in the absence of clear central guidance, co-ordination and standards, individual departments remain responsible for determining many of the implementation details for online services. It was suggested that this may lead to “siloed implementation”, with departments failing to fully capitalise on the potential to rethink and redesign service delivery. DoF told us that it challenges the silo behaviour which exists as a result of political, local and central government structures, but has no authority to force change.

The Digital Transformation Programme is led by the Department of Finance and aims to improve access to government services

1.22 The NI Direct Programme was established in 2008 as part of the response to a government target to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of public services. The target aimed to deliver wider public sector reform and generate efficiency savings while bringing government closer to people, revitalising public services and responding to the increasingly diverse nature of society. Public services were to be more accessible, accountable and responsive to individual needs and lifestyles. The target acknowledged that improving the public services experience and outcomes for everyone benefits society by removing administrative boundaries and promote working together.

1.23 The NI Direct Programme sought to improve access to government services by developing a multi-channel approach utilising the web, telephone and Short Message Service (SMS) text channels. It represented the response to a series of key strategic reform initiatives and transformation proposals across the United Kingdom which aimed to modernise government and improve the commonality and accessibility of information for the customer while delivering a more efficient service for the customer and taxpayer. Responsibility for delivering the NI Direct Programme fell to the Delivery and Innovation Division within DoF.

In 2008, DoF entered into a £5.7 million contract to deliver NI Direct Phase 1 of the programme. Four years later, it entered into a 7 year, £50 million Strategic Partner Project with British Telecommunications plc (BT) for delivery of Phase 2

1.24 The NI Direct Phase 1 contract was awarded in July 2008 as a two year contract with options to extend on a yearly basis up to four years. The original contract value was £5.7 million. The contract was formally extended twice, up to July 2011 and July 2012, and a further short-term extension was negotiated up to October 2012 to enable a new Strategic Partner Procurement contract to be put in place. Total cost under the NI Direct Phase 1 contract amounted to £6.5 million (14 per cent over estimate).

1.25 NI Direct Phase 1 allowed DoF to take a step forward in transforming the Northern Ireland Customer Interaction Centre (NICIC) from an exclusively switchboard service into a modern customer contact centre, providing information and simple transactional services on behalf of a number of anchor tenants.

1.26 Four years later, in October 2012, DoF agreed a £50 million contract (the Strategic Partner Project) with British Telecommunication Group plc (BT) to provide Information Technology (IT) solutions, skills and capabilities to support Northern Ireland departments and organisations move citizen services online. The contract period (or initial term) was specified as 84 months (7 years) from the commencement date (October 2012). The contract included an option to extend the initial term for one further period of 3 years (to October 2022) on the same terms. In order to extend the contract, DoF was required to notify BT no later than 12 months prior to the end of the initial term (that is, by October 2018).

1.27 The contract included £20 million to cover the cost of the NI Direct contact centre. The remaining £30 million was intended to cover:

- Service Management services;

- Managed Information Communications Technology (ICT) Services;

- Business Development Services; and

- Optional Specialist Business and ICT services designed to supplement internal resources such as channel migration, business transformation, process design, business change, ICT development services etc.

The 16 by 16 initiative sought to ensure that at least 16 digitally transformed services were delivered by March 2016

1.28 In May 2013, DoF produced the Citizen Contact Strategy. It confirmed that all departmental public services with over 10,000 transactions each year should meet the new ‘digital first’ standards, with digital online as the primary means of interacting with citizens or businesses. The Citizen Contact Strategy recommended that every department/public sector organisation undertake a detailed landscape review of its citizen contact.

1.29 In December 2013, DoF produced a high level Landscape Review to highlight those areas where the Northern Ireland Civil Service and the wider public sector could significantly improve the public’s experience of contacting government. Ultimately, the exercise was intended to prioritise projects and produce a roadmap for digital transformation. As part of its work to produce the Landscape Review, DoF reviewed over 120 citizen-facing services across 12 departments. That review identified 18 services with potential for improvement through digital delivery (Appendix 1).

1.30 DoF recognised that the focus of the NI Direct Programme needed to shift toward digital transformation. New governance structures were introduced and, in January 2014 a DoF Director of Digital Transformation was appointed. In April 2014, a strategic programme “Digital Transformation Programme” (DTP) was established with key targets (the delivery of the 16x16 initiative), whereby at least 16 digitally transformed services were to be delivered by March 2016 and the number of digital transactions was to be increased to 3.5 million (part of the Stormont House Agreement). Not all projects undertaken to achieve this target were procured through the Strategic Partner Project. Figure 1.1 shows that, by March 2016, 4.5 million digital transactions were completed across 20 online services.

Figure 1.1 Number of online services available and digital transactions completed

|

DTP Targets: |

Progress by March 2016: |

Progress by March 2019: |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Source: DoF

Note: These performance figures include those services procured through the NI Direct Strategic Partner Project and those procured through various other procurement routes.

1.31 The Digital Transformation Programme sought to transform citizen-facing service delivery across Northern Ireland public sector organisations and, as a result, provide a more efficient service for both customer and taxpayer. It involves:

- Digital First: where departments and agencies must ensure that digital online services are the primary means of interacting with citizens when developing new services or reviewing existing provision;

- NI Direct Preferred: where departments and agencies, when they are developing or reviewing service provision involving online or telephone interaction with citizens, will favour use of the …[Strategic Partner Project] unless the approved business case determines an alternative option; and

- NI Direct Portal: where citizens must be able to use the NI Direct web portal to access all online services provided by departments and agencies even in exceptional cases where such services are hosted elsewhere. The nidirect.gov.uk website was launched in March 2009.

A Strategy for Digital Transformation of Public Services was published in 2017

1.32 On 30 November 2017, DoF published a digital transformation strategy. The Strategy was designed “to help deliver more modernised services to the public and businesses through the better use of technology, work processes and investment in people”, took account of the findings of external reviews of Northern Ireland public sector Digital Transformation Programmes and was aligned with the eHealth and Care Strategy for Northern Ireland. The Strategy reported that the DTP was aligned to the PfG commitment to deliver 70 per cent of all citizen transactions with government online by 2019.

1.33 The Strategy is underpinned by a Digital Transformation Programme Strategic Delivery Plan for the period 2017–2021, Delivering Better Public Services through Technology (the Northern Ireland Civil Service ICT Strategy 2017-2021) and Cyber Security: A Strategic Framework for Action 2017-2021.

In June 2017, it was recognised that expenditure through the Strategic Partner Project would exceed the estimated contract value. By 31 March 2018, actual expenditure under the Strategic Partner Project contract amounted to almost £62 million (against the original contract value of £50 million)

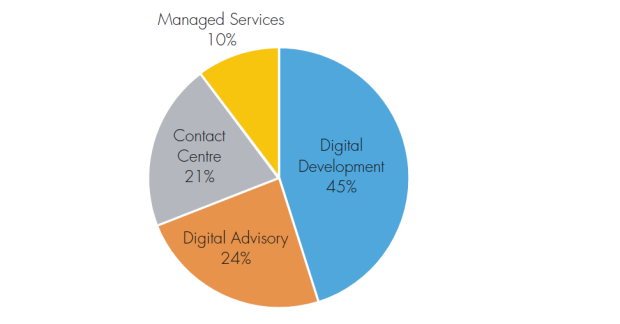

1.34 By 31 March 2018, actual expenditure under the Strategic Partner Project amounted to £62 million against the original contract value of £50 million. Figure 1.2 shows that 45 per cent (almost £28 million) was spent developing applications and solutions (Digital Development), 24 per cent was incurred on Discovery Phase and Consultancy costs, 21 per cent related to the costs of managing the contact centre and the remaining 10 per cent related to the cost of managing applications hosted on the NI Direct platform.

1.35 Figure 1.3 provides a breakdown of the major components of the Strategic Partner Project expenditure to 31 March 2018. These include the costs of the contact centre, developing 13 major applications and solutions, two major consultancy projects and developing a number of cross- cutting applications. Appendix 2 provides background on the nature of the 13 major individual projects.

1.36 In our audit of DoF’s 2016-17 financial statements, we had highlighted that the capital costs associated with the Strategic Partner Project exceeded the amount in the original business case by almost £2 million. We had also noted that the latest estimates of total expenditure through the £50 million contract were likely to be in the region of £80 million. We recommended that DoF develop more robust mechanisms to monitor the expenditure on contracts.

1.37 In our audit of DoF’s 2017-18 financial statements, we noted that despite the significant time already spent developing an improved monitoring system, DoF was unable to fully attribute all expenditure under the Strategic Partner Project to individual projects.

Figure 1.2: Breakdown of Strategic Partner Project Expenditure to 31 March 2018

Figure 1.3: Breakdown of costs through the Strategic Partner Project (Figures provided from the DoF Tracking System)

|

Major Digital Development Projects Funded |

Capital Costs to 31 March 2018 (£s) |

Advisory Costs to 31 March 2018 (£s) |

Managed Service Costs to 31 March 2018 (£s) |

Total Expenditure to 31 March 2018 (£s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Driving Vehicle Agency Transformation Project |

5,980,100 |

1,177,700 |

816,300 |

7,974,100 |

|

2. Apply for life event certificates – NIROS Project |

3,170,900 |

– |

742,800 |

3,913,700 |

|

3. Rates Rebate Application |

3,098,200 |

402,900 |

– |

3,501,100 |

|

4. Apply for Access NI checks |

2,027,600 |

– |

651,500 |

2,679,100 |

|

5. Tourism NI Technology Platform |

1,550,800 |

174,200 |

1,135,400 |

2,860,400 |

|

6. Compensation for criminal injuries and criminal damage |

1,663,700 |

91,600 |

312,100 |

2,067,400 |

|

7. OSNI Map Shop– CAMEOII Project |

973,000 |

– |

441,400 |

1,414,400 |

|

8. Research Family History – GeNI Project |

1,008,100 |

117,000 |

509,200 |

1,634,300 |

|

9. Landlord Registration |

867,200 |

– |

361,200 |

1,228,400 |

|

10. Purchase a fishing licence/permit |

1,125,300 |

116,500 |

200,700 |

1,442,500 |

|

11. Pay Rates |

185,100 |

– |

702,500 |

887,600 |

|

12. Submit a Planning/Water Appeal (PACWAC) |

652,000 |

– |

92,500 |

744,500 |

|

13. Digitisation of Legal Aid |

4,504,500 |

367,300 |

– |

4,871,800 |

|

Total |

26,806,500 |

2,447,200 |

5,965,600 |

35,219,300 |

| Other (covering various smaller payments across several projects) |

1,149,900 |

12,401,900 |

377,800 |

13,929,600 |

| Contact Centre Costs |

|

|

|

12,808,400 |

|

Overall Total |

27,956,400 |

14,849,100 |

6,343,400 |

61,957,300 |

|

Major Digital Advisory Service Projects |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Debt Transformation |

1,541,400 |

||

|

2. Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Reform |

5,013,000 |

||

|

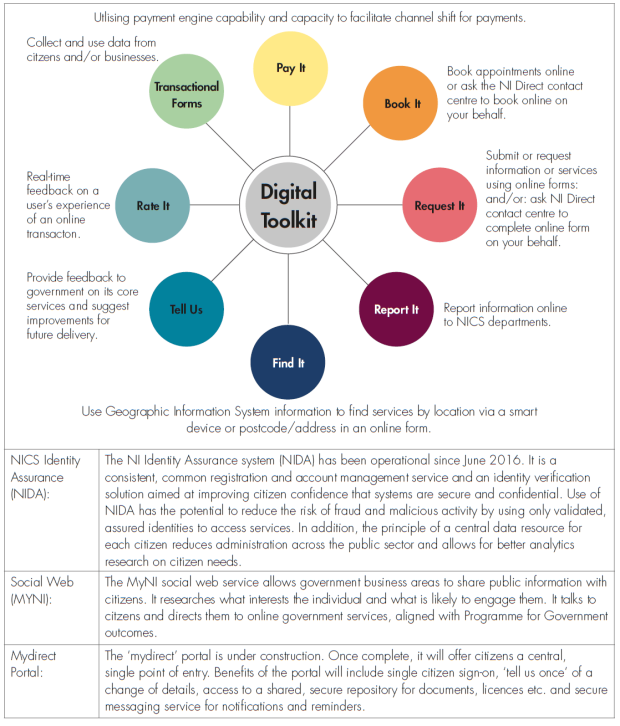

3. Cross-cutting Applications: |

Digital Toolkit |

1,378,400 |

3,077,900 |

|

NI Civil Service Identity Assurance |

812,900 |

||

|

Mydirect Portal |

644,400 |

||

|

Social Web |

242,200 |

||

| Other |

2,769,600 |

||

|

Total Other |

12,401,900 |

||

| Advisory Costs relating to Major Projects (breakdown provided above) |

2,447,200 |

||

|

Total |

14,849,100 |

Source: DoF

Our previous public reporting work has highlighted concerns similar to those identified in this report

Electronic Service Delivery within Northern Ireland Departments

1.38 In 2007, we published a report examining Electronic Service Delivery within Northern Ireland Government Departments. That report considered progress in achieving a Northern Ireland Executive target to have 100 per cent of key services capable of being electronically delivered by the end of 2005.

1.39 In that report, we were critical of the limited extent to which departments had complied with the guidance issued by the Northern Ireland e-Government Unit - a Unit set up to promote, monitor and report on electronic service delivery. We found that departments had not initially carried out a baseline audit of all services provided, had not prioritised services by volume, frequency, cost and value of transaction and had not consulted with customers/service users before including services in the target.

Transforming Land Registers: The LandWeb Project

1.40 In 2008, we published a report on Transforming Land Registers: The LandWeb Project. That report examined the arrangements surrounding a 1999 Land Registers Northern Ireland Agreement with British Telecom (acting as Strategic Private Finance Initiative, Information Computer Technology partner).

1.41 We concluded that the project had delivered significant improvements to the Land Registers’ operations and had benefited customers. We were, however, critical of the fact that the Agreement precluded Land Registers from obtaining information on the make-up of BT charges, costs, overhead and profits. In addition, we were concerned that a full benefits realisation/post- implementation review had not been completed at the time of our review. We noted that the scope of the initial project had been expanded, resulting in additional payments of £19.2 million to British Telecom, and found little evidence to support over £9 million in changes to the Agreement. In addition, one of the key drivers for the project, reducing fees to customers, had not been realised.

1.42 That report was considered by the Public Accounts Committee (PAC). Its report (dated 30 May 2010) raised concerns over DoF’s justification for increasing the contract price with BT from £17.5 million (over ten years) to £46 million (over 17 years) in the space of eight months. The PAC concluded that the deal negotiated, with its incremental implementation approach, had been more lucrative to British Telecom than originally envisaged. DoF acknowledged that its negotiations could probably have been better. The PAC identified evidence of poor project management, short comings in risk management and a lack of necessary skills and experience in the Land Register’s project team before, during and after the procurement and was not convinced that the market was tested properly.

The National Audit Office has issued a number of reports on digital developments in England

1.43 In 2011, the National Audit Office (NAO) issued a report on the cost and performance of Gateway (which enables users of public bodies’ online services to connect, exchange personal information securely and undertake financial transactions integral to the services) and two government services (Directgov and Business.gov). The report concluded that progress had been made in making it easier for people to access government information and services online but highlighted that, in the absence of robust data on the costs and benefits of spending, no conclusion could be made on the extent to which value for money had been achieved.

1.44 Less than two years later, the NAO issued a second report in this area which tested the assumptions made about users in the government digital strategy. The NAO noted that, since it had last reported, government plans had moved from the consolidation of websites to the “more fundamental need to redesign public services with users at the heart”. The NAO concluded that there was scope for using online public services more and that the government’s desire to make public services “digital by design” was broadly acceptable to people and small and medium-sized businesses. The report identified that the government needs to put plans into action to help those people who did not identify online as their preferred access channel.

1.45 In 2017, the NAO issued its latest report in this area, highlighting that some improvements had been made but cautioning that digital transformation had had a mixed track record across government and had not yet provided a level of change that will allow government to further reduce costs while still meeting people’s needs. The report concluded that there is still a long way to go.

1.46 The 2017 report reviewed the role of the Government Digital Service (GDS) in supporting transformation and the use of technology across government. It identified that the GDS has successfully reshaped government’s approach to technology and transformation but had found it difficult to redefine its role as it has grown and transformation has progressed. The NAO noted that the GDS has now adopted a more collaborative and flexible approach with departments and has established strong controls over spending. The NAO considered that the combination of strict controls and uncertainty about guidance made it difficult for departments to understand assurance requirements.

Part Two: Contract Management of the Strategic Partner Project by the Department of Finance

Phase 1 of the NI Direct Programme demonstrated and quantified the benefits of a single NI Direct contact centre

2.1 The purpose of the Phase 1 contract was to demonstrate and quantify the benefits of a single contact centre (to replace the old switchboard service (the Northern Ireland Customer Interaction Centre)). The total value of the contract was £5.7 million and the contract was awarded for an initial two years (with two annual options to extend). The contract was extended for the specified two additional years (up to July 2012) and subsequently for a further short period until the new Strategic Partner Project Contract was in place.

2.2 Phase 1 was completed by October 2012 at a cost of £6.5 million (14 per cent over estimate). As a result of Phase 1, several public sector service provider telephone numbers were consolidated, the number of first call resolutions was improved, and an intelligent directory service was created which directs more difficult queries to the most appropriate person.

2.3 A DoF Post Project evaluation of Phase 1 was completed in April 2011 and concluded that the project had been managed well and was within time and budget requirements. The project had virtually met all of its objectives and made significant progress in the realisation of benefits.

Phase 2 extended use of the NI Direct contact centre across the broader Northern Ireland public sector and its use was mandated across departments to improve telephone and online access to government services

2.4 Phase 2 of the NI Direct Programme, enabled through the Strategic Partner Project, involved extending use of the contact centre across the broader Northern Ireland public sector and procuring expertise to develop online services. In September 2012, all departments were notified that the Permanent Secretaries’ Group had agreed that, when developing or refreshing programmes involving online or telephone interaction, there should be a presumption in favour of using the Strategic Partner Project unless the approved business case determined an alternative option. In October 2012, DoF appointed BT as its Strategic Partner.

2.5 The Strategic Partner Project had a contract value of £50 million; £20 million was to cover the cost of the NI Direct contact centre which handles around two million public sector calls each year - services include the Flooding Incident Line, provision of child maintenance support, advice and guidance and assisted digital services to support Landlord Registration. Following the 2012 direction, the contact centre customer base increased substantially. Despite this, call traffic has remained constant showing a slight decreasing trend in 2018.

2.6 The remaining £30 million was allocated for ‘optional services’ which include Digital Development, Digital Advisory and Managed Services. In effect, in line with a direction from the Permanent Secretaries’ Group, expenditure under the optional services element of the contract was to be considered the preferred procurement option for developing or refreshing programmes involving online or telephone interaction with the public, unless the business case determined an alternative option.

2.7 All payments to BT under the Strategic Partner Project are made by DoF. In cases where the costs relate to services received by departments and/or agencies other than DoF, amounts due are recouped from the relevant body. Responsibility for monitoring the overall costs incurred under the contract falls to DoF while responsibility for managing individual projects falls to the relevant body. DoF had specific responsibility for:

- Managing the BT contract;

- Managing the relationship with BT and relevant customers;

- Reviewing and challenging BT costs; and

- Assessing the value for money of proposals provided by BT, arranging independent assessment and benchmarking of costs where necessary.

Expenditure through the Strategic Partner Project has significantly exceeded estimates and the contract value

2.8 By June 2017, expenditure predicted to October 2019 was estimated to be in the region of £70 million; £20 million (40 per cent) in excess of the total contract value. We note that DoF sought legal advice which recommended that “given that the situation is not clear cut, it would be sensible for the Department to seek to keep the overall contractual value at the lower end of the current range of forecast spend [£66 million]”. Having received advice, the DoF Accounting Officer approved an increase in the overall contract value to the predicted £70 million. At that stage, DoF intended to terminate the contract at the end of the 84 month period specified in the contract (that is, October 2019). The increase allowed DoF to ensure continued use of the contact centre and managed services but, given the expenditure through the Strategic Partner Project, no further new transformational projects were procured through the Strategic Partner Project.

2.9 By October 2018, it transpired that expenditure up to the end of the contract (October 2019) was likely to be in the region of £77 million, rather than the previous estimate of £70 million. At this stage, DoF stated that the contract duration was for a period of 10 years (to October 2022) with an optional break point in October 2019. However, we identified that the original contract terms clearly state that the contract was for an initial period of 84 months (to October 2019) with an option to extend for three years (to October 2022).

2.10 In October 2018, DoF stated that it would not be possible to terminate the Strategic Partner Project in October 2019, because alternative arrangements have not been put in place to ensure continuity of services. We welcome the “deep-dive” review undertaken by the Department’s Audit and Risk Assurance Committee at that time which explored the financial and contractual position with the Strategic Partner Project. Following that review, the Accounting Officer approved the three year contract extension (to October 2022). By October 2022, Departmental officials expect that total expenditure incurred will amount to £110 million – over twice the original contract value.

2.11 Figure 2.1 provides a breakdown of the actual costs to 31 March 2018, anticipated costs to 31 October 2019 and anticipated costs to the end of the agreed extension period (31 October 2022).

Figure 2.1: Strategic Partner Project Costs

|

Cost Category |

Description of Costs |

Actual Costs to31 March 2018£ million |

Original Estimated Costs (to 31 October 2019)£ million |

Predicted Costs to 31 October 2019£ million |

Predicted Costs to 31 October 2022£ million |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Contact Centre |

Charges relating to the operation of the contact centre |

12.81 |

20.00 |

16.60 |

|

|

Managed Services |

Running costs for applications hosted on the BT platform |

6.34 |

Total Costs across these categories were estimated at £30 million. |

10.90 |

|

|

Optional Services:Digital Development |

Capital costs for developing applications and solutions |

27.96 |

33.30 |

|

|

|

Optional Services: Digital Advisory |

Resource costs for solution development – relating mainly to Discovery and Consultancy costs |

14.85 |

16.70 |

|

|

|

Other Costs (including Exit Costs) |

|||||

|

Total |

61.96 |

50.00 |

77.50 |

110.00 |

Source: DoF

In January 2016, a Gateway review questioned whether the contract had outlived its usefulness and welcomed the move to a more agile approach

2.12 In January 2016, a Gateway review of the Strategic Partner Project identified that “there are causes to question whether the contract as written continues to fit with the business being conducted” and concluded that “… there is growing evidence that the contract, as let, may have outlived its usefulness and the [Northern Ireland Civil Service] … might be better served by a more agile approach”. DoF told us that, at the time, the Gateway Review team was aware that it was working with BT and had changed to a more agile approach to meet customer needs.

2.13 The Gateway review team was critical that the Strategic Partner (BT) was failing to provide transparency of their annual accounts despite a contractual undertaking to provide the information and for “open book accountancy”. As a consequence, the review team concluded that DoF was uninformed as to whether it was entitled to gain share settlements for any of the years since commencement of the contract. BT commented that, whilst the failure to comply with this contractual obligation in the past is highly regrettable, reviews indicate that no gain share will be invoked. In 2008, we raised similar concerns in relation to the LandWeb project.

2.14 The review team acknowledged that the move from waterfall to agile development was welcome but questioned whether the additional cost of layering BT above subcontractors added any project value. Further, it identified that “innovation received from the Strategic Partner was ’patchy’ with the bulk of innovation coming either from the subcontractors or from within the Northern Ireland Civil Service”.

In 2016, DoF’s Internal Audit Service was critical of DoF’s management of the Strategic Partner Project Contract

2.15 In 2016, DoF Internal Audit (IA) reported the results of its review of the project management of the Strategic Partner Project. IA identified a number of areas where controls were not effective and provided a ‘limited’ audit opinion making a total of 27 recommendations. In broad terms, Internal Audit was critical that:

- DoF had overcommitted expenditure against the contract by £17.2 million (34 per cent over the original budget) by August 2016 and prior approval for this had not been obtained.

- DoF was not in a position to provide details of actual spend against the contract and was not actively managing the contract with BT.

- DoF had not received (or reviewed) BT annual audited project accounts, gain share calculations and Certificate of Costs and Benefits (in accordance with the Agreement).

- The scalability of the financial modelling and resource compliment had not been considered during the discovery and statement of requirement phases of the contract.

2.16 IA published the results of a follow-up review in September 2017 and confirmed that 12 (of the 27) recommendations had been fully implemented, 14 recommendations had been partially implemented and one recommendation had not been implemented. On the basis of the follow-up review, IA collated its previous work and made a further 15 recommendations. By March 2018, DoF advised that all but one of the remaining recommendations had been implemented.

2.17 In relation to the receipt and review of audited BT project accounts, IA noted that accounts had been received for the periods to 31 March 2013 and 2014 but had not been reviewed by DoF. Accounts for the periods to 31 March 2015 and 2016 remained outstanding. BT told us that it is working on providing accounts for 2016 and 2017 as soon as possible and confirmed that, going forward, all accounts will be provided within the timeframe stipulated in the contract. In a report we issued in 2008 (Transforming Land Registers: The LandWeb Project) we raised similar concerns in relation to obtaining information from BT.

In 2017, external consultants reported that the Strategic Partner Project had delivered value for money but highlighted a number of concerns

2.18 DoF commissioned Gartner Consulting to undertake an Independent Post Project Evaluation on the success of the Strategic Partner Project with BT. Gartner produced a report in November 2017 which concluded that, since costs across each component were within the market range and below the market average, value for money had been achieved. The review identified that DoF had provided value-adding services to the projects and that use of the agile development methodology had a positive impact on projects and ensured greater user involvement during the development process. A summary of the findings and recommendations is provided at Appendix 3.

2.19 For each of the three projects Gartner examined, it confirmed that, where a project had been completed, project objectives had been met. Some issues with external ID verification functionality and the contractual spend limit had “seriously impacted on a couple of projects, requiring additional procurements and delays to realising functionality and, therefore, the realisation of benefits”. Given this, the consultants recommended that “[DoF] establish a portfolio view of quantified benefits to justify its on-going value”. The consultants were also critical that there did not appear to be any project prioritisation process to ensure that the initiatives of greatest benefit were progressed.

2.20 The consultants confirmed that DoF had a strong relationship with BT. While this was seen as a strength, the consultants highlighted that, because of this, regular cross-checking to contract document had been less of a focus. They commented that, given the length of the contract (at over 1,000 pages) and its failure to fully apportion roles and responsibilities, additional effort was required to manage and ensure compliance. They considered that the absence of a dedicated and skilled contract management resource was a deficiency in DoF’s approach.

2.21 As a result of the review, the consultants highlighted the following:

- Ensure future contracts set out the roles, responsibilities (particularly between DoF and departments), metrics and outcomes;

- Define a regular, formalised management process to understand the strategic needs of departments and other stakeholders;

- Implement formalised contract management processes;

- Through communication and training, ensure that departments and other stakeholders are aware of the contract usage and mechanisms;

- Ensure sharing of lessons; and

- Consider inclusion of project break points.

2.22 DoF told us that it has taken on board all of the consultants’ recommendations and other lessons to inform the new Strategic Partner Project (due for implementation in 2022). DoF has put new mechanisms in place within the Digital NI Enabling Programme to ensure new contractual arrangements are clear and concise with Service Level Agreements which drive effective contractor behaviour.

DoF struggled to provide us with a breakdown of costs by individual project

2.23 In 2016 (four years after Phase 2 was awarded to BT) (see paragraph 2.15), Internal Audit noted, at the outset of its audit, that despite DoF’s tracking system (introduced in 2014), it was not able to provide details of actual spend against the contract and was not actively managing the contract with BT. One year later, the external consultants were critical of the absence of a dedicated and skilled contract management resource within DoF.

2.24 In response to the criticisms, DoF obtained a dedicated resource to track payments, however, when we asked for a breakdown of total costs paid to BT, DoF was still not in a position to provide complete cost records. The breakdown (by category and project) was prepared retrospectively and was finally available by September 2018.

2.25 DoF accepts that its existing system (the Tracker) is not a viable long term solution for financial monitoring of expenditure.

Capital expenditure on a number of projects procured through the Strategic Partner Project exceeded original estimates

Digital Development projects

2.26 Figure 1.3 shows that almost £28 million was incurred on the digital development of solutions and applications. This included 13 major digital development projects procured through the Strategic Partner Project at a cost of almost £27 million. The DoF Tracker provides additional information on the estimated and actual costs incurred on individual projects. This relates only to capital costs passed through the Strategic Partner Project. It does not include advisory or managed service costs through the Strategic Partner Project or additional project costs incurred by departments.

2.27 We reviewed the Tracker information and noted that the capital costs on three (of the 12 completed) major digital development projects exceeded original estimates by 10 per cent or more (see Figure 2.2). DoF explained that project expenditure increases occurred for a number of reasons including, for example, scope change identified during the discovery phase and pointed out that additional spend is subject to revised business case approvals. DoF told us that the change from waterfall to agile has ensured visibility of potential overspend allowing impact to be assessed and decisions to be made. BT told us that delivery delays and cost overruns were, in most cases, caused by changes in scope and additional functionality requirements from the client which resulted in incremental time to delivery.

Figure 2.2 Capital overspends on major Digital Development Projects funded through the Strategic Partner Project

|

Digital Development Project |

Total Strategic Partner Project Costs (£s) |

Estimated Capital Cost(Note 1) (£s) |

Actual Capital Costs (£s) |

Capital Overspend (£s) |

Percentage Overspend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fishing Licence |

1,442,500 |

945,000 |

1,125,300 |

180,300 |

19% |

|

Research Family History – GeNI Project |

1,634,300 |

889,000 |

1,008,100 |

119,100 |

14% |

|

Compensation for criminal injuries and criminal damage |

2,067,400 |

1,490,900 |

1,663,700 |

172,800 |

12% |

Source: DoF

Note 1: Estimated Capital Costs were obtained from individual departmental business cases.

Digital Advisory projects

2.28 Figure 1.3 shows that total expenditure on Digital Advisory costs to 31 March 2018 amounted to £14.85 million. This includes just over £5 million relating to the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs’ (DAERA) Common Agricultural Programme (CAP) Reform work and just over £1.54 million relating to the Debt Transformation Programme within the Social Security Agency. Actual costs (to date) for both these projects have considerably exceeded original estimates.

- DAERA CAP Reform: £5,013,000

DAERA used the Strategic Partner Project to procure assistance with aspects of its CAP Reform Programme (introduced in 2015). This allowed DAERA to embed ICT specialists into its agile software development teams. The reform project integrated components from the NI Digital Toolkit rather than duplicating code or functionality. We analysed payments made through the Strategic Partner Project to 31 March 2018 and noted that CAP Reform payments of £2,791,852 were made under the original agreement with a further £2,221,212 paid in relation to contract extension since December 2015. Total funding paid therefore amounted to £5,013,000 (under Discovery and Consultancy Costs) – that is almost twice the amount originally estimated for procurement through the Strategic Partner Project. -

Social Security Agency Debt Transformation Project: £1,541,400

The Social Security Agency (SSA) (now part of the Department for Communities) used the Strategic Partner Project to procure assistance with the development and implementation of a new Debt Strategy. The project was intended to build capacity and modernise systems, processes and structures in order to maximise the recovery of Government Debt whilst providing support to citizens in need. As a result of the UK Welfare Reform programme, the value of DfC’s debt book was predicted to increase from around £146 million in 2016 to around £413 million in 2020-21. The debt transformation programme (of which this consultancy work was a small part) enabled DfC to absorb these policy changes, manage greater levels of debt recoveries and deal with the resultant increase in customer contact without needing to significantly increase numbers of staff.At the initial development stage, the SSA identified the need to secure additional resources, estimated to be in the region of £726,000. In 2013, the SSA engaged a team of external contractors through the Strategic Partner Project on both a consultancy and staff substitution basis. Following a series of extensions to the project, actual costs (at £1,541,400) were more than twice the amount originally estimated for procurement through the Strategic Partner Project. While DfC acknowledges the overspend, it considers that the project delivered a positive outcome when set against the scale of the organisational challenge and change programme.

As a result of overspends, funding for elements of one programme was terminated

2.29 The Driver and Vehicle Agency (DVA) had identified an urgent need to replace the 30 year old legacy application for providing driving licences and applied to use the Strategic Partner Project as a procurement vehicle. In August 2013, DoF advised the DVA that it “would not be in a position to provide the total solution [DVA] require[s] through the [Strategic Partner Project] contract due to the estimated total value of £7.9 million set-up with £85 0,000 per annum revenue”.

2.30 In the Department’s Landscape Review, Driver Licensing was identified as a service with potential for inclusion in the 16 by 16 initiative. In April 2014, DoF wrote to DVA to advise that the NICS Assessment Panel had reviewed the Driver Licensing Statement of Requirements and concluded that a “different approach needs to be taken”. DoF offered to invest support, including the use of the NI Direct Strategic Partner contract, “into a new approach which should ensure a digitally transformed service for the citizen”. This offer was accepted by DVA and work commenced. The Driver and Vehicle Agency initiated a major transformation programme across all its services. The transformation programme involved the following projects:

- Driver licensing system;

- Compliance and enforcement system;

- Commercial licensing;

- Driver and vehicle testing; and

- Booking and rostering.

2.31 During the preliminary phases of these projects, the DVA had an understanding that all DVA planned work could be delivered through the Strategic Partner Project. However, in May 2017, DoF informed DVA that it could make no further use of the contract because the financial ceiling had been reached. We noted that despite the 2013 DoF decision not to progress this project through the Strategic Partner Project on the basis of the high cost, a total of £7,974,100 has been spent on DVA transformation.

2.32 The DVA assessed the position and concluded that the outstanding work (relating to Enforcement and Compliance, Operator Licensing and Testing and designing the Corporate Data model) was so far advanced that it was not possible for the work to pass to a different supplier. As a result, the DVA entered into a two year, £7.2 million direct award contract with the original contractor (BT). The Booking and Rostering project had not progressed to the same extent and the contract was awarded through open procurement.

2.33 The decision by DVA to enter into a direct award contract with BT (for elements which were well progressed) is understandable, however the use of such contracts is not encouraged because it is difficult to demonstrate the extent to which they offer value for money.

We noted that time delays were experienced with five projects

2.34 Effective project management involves planning and controlling resources to ensure delivery of the required product within agreed time and cost parameters. We compared delivery for each project (in terms of time and cost) against the original plans outlined in the project business cases. Eight of the digital development projects procured through the Strategic Partner Project were delivered within the agreed timescales. The remaining five (including three projects which pre-dated the introduction of the Digital Transformation Programme) experienced delivery delays as follows:

- Tourism NI

The website development phase was delayed by almost two years as a result of scoping, technology, internal resourcing, supply chain and content issues. DfE also informed us that, external consultants who reviewed the project identified that while there were issues with the technical capability and availability of staff in Tourism NI, BT had failed to proactively engage and manage project delivery (specifically managing third party suppliers). - Compensation Services

Go-live for the project was delayed by 18 months due to issues which included securing verification centres. - Planning Appeals Commission and Water Appeals Commission (PACWAC)

Slippage of 8 months was experienced with this project due to disagreements around functional specifications. Search portal availability, reporting modules and letter modules were not working as anticipated. - Online mapping products (CAMEO II)

Project was slightly delayed (by 7 weeks) because of an under estimation of development time required by the contractors/sub contractors. - Digitisation of Legal Aid

Digital Account Creation went live in January 2019 and the Case Management system, is expected to go-live in July 2019 (that is, 22 months later than originally anticipated). Initial delays arose because of limited resources within the Department of Justice. Further delays arose due to client concerns over the quotes for the work, the identification of key concerns following an internal peer review of the project and concern about stakeholder readiness. In addition, the original business case was reworked to ensure the project was fully transformational and that staff savings were maximised.

We identified from various departmental reports that some teething problems arose with early projects procured through the Strategic Partner Project

2.35 Completion of post project evaluations (PPEs) ensures that lessons (positive and negative) are learned from individual projects. In relation to the 12 major, completed, digital development projects we examined, seven had a completed PPE. In two cases (Compensation Services and Driver Licence Replacement) it was too early to expect a PPE. In two cases (Pay Rates and Landlord Registration) no PPE had been prepared.

2.36 The first project progressed was the Genealogy Project for Northern Ireland (GeNI). This was a DoF project designed to upgrade online and public search room access to a selection of historical records and images, and provide a more sophisticated and secure online certificate ordering system. The PPE report highlighted several issues which impacted on delivery of the proposed end to end solution. In particular, it noted that:

- At the outset BT did not provide a detailed, technical build that constituted a full end-to-end solution;

- Governance arrangements and roles were not sufficiently robust;

- Engagement with all key players happened too late in the process; and

- The project was brought on board while the NI Direct infrastructure was still being developed.

2.37 The next major project to be commissioned was online mapping system (CAMEO I). This project involved replacing and enhancing the existing CAMEOI (also known as Ordnance Survey Northern Ireland (OSNI) online map shop) which provided online purchase or licence of Ordnance Survey mapping products and was at the end of its contract life. The PPE confirmed that in general, the arrangements with BT worked well but it highlighted that:

- BT underestimated the development requirements of such a major project;

- The contractor, on occasion, was inflexible (and charged) to make changes; and

- Tension arose over BT’s interpretation of the agile method – this led to confusion over agreed changes.