Abbreviations

AD Anaerobic Digestion and/or Anaerobic Digester

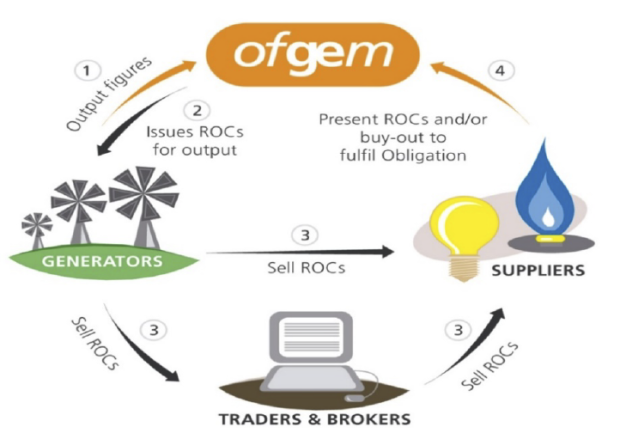

AFBI Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute

BEIS Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

C&AG Comptroller and Auditor General for Northern Ireland

CEPA Cambridge Economic Policy Associates

CfD Contracts for Difference

CfE Call for Evidence

CHP Combined heat and power

DfE Department for the Economy

DETI Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

DoF Department of Finance

DfI Department for Infrastructure

EN Enforcement Notice

EU European Union

FIT Feed-in Tariff

GB Great Britain

ITAR Independent Technical Assurance Report

kW Kilowatt

kWh Kilowatt hour

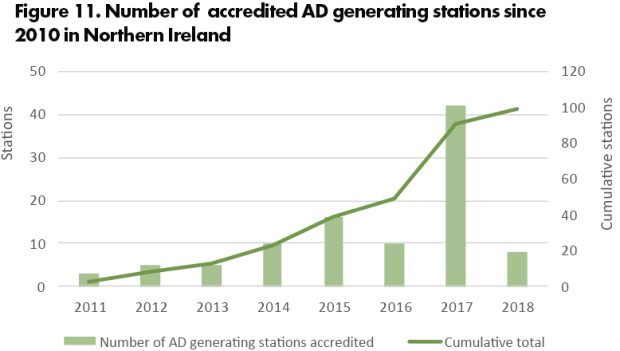

LPS Land and Property Services

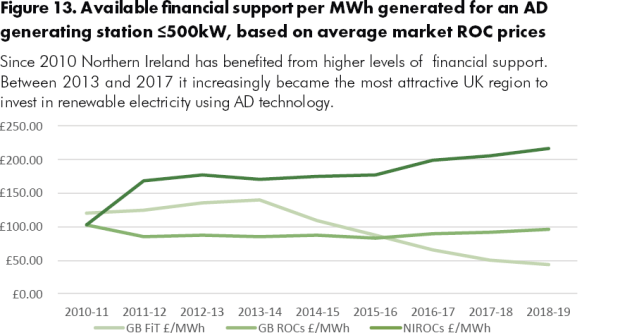

MW Megawatt

MWh Megawatt hour

NI Northern Ireland

NIAUR Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulation

NIEA Northern Ireland Environment Agency

NIRO Northern Ireland Renewables Obligation

NIROC Northern Ireland Renewables Obligation Certificates

OFGEM Office of Gas and Electricity Markets

RO Renewables Obligation

ROC Renewables Obligation Certificate

SN Stop Notice

UK United Kingdom

VAT Value Added Tax

WML Waste Management Licence

Key Facts and Forecasts

40% Northern Ireland’s 2020 target percentage of electricity to be consumed from renewable sources

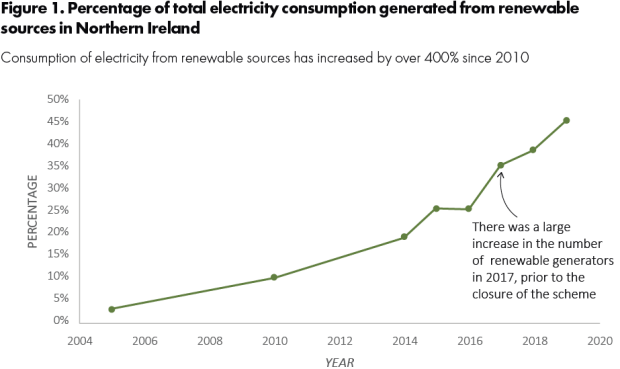

46.8% the actual percentage of electricity consumption generated from renewable sources in Northern Ireland for the 12 month period ending 31 March 2020.

85.4% percentage of renewable electricity generated from onshore wind for the 12 month period ending 31 March 2020

5.3% percentage of renewable electricity generated by biogas for the 12 month period ending 31 March 2020

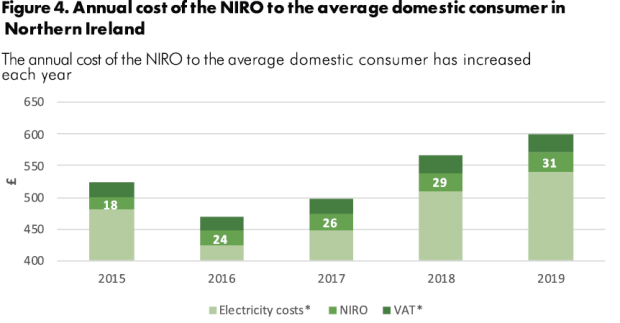

£31 the average cost, to the average domestic electricity consumer in Northern Ireland (5 per cent of the average total electricity bill), of renewable electricity support schemes in 2019

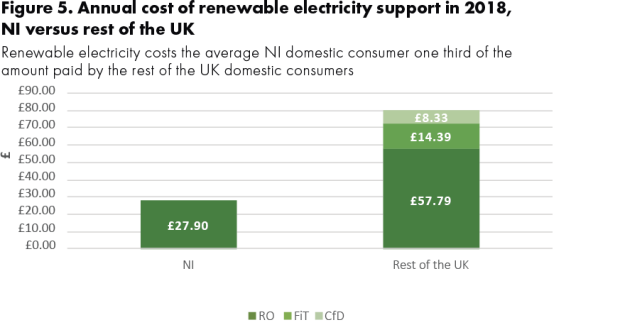

£80 the average cost to the average domestic electricity consumer in Great Britain (7 per cent of the average total electricity bill), of renewable electricity support schemes in 2019

3.5 approximately three and a half times as many AD based generating stations per sq. km of land in Northern Ireland than in Great Britain

3 almost three times as many stand-alone wind turbines per sq. km of land in Northern Ireland than in Great Britain

£1.17 billion the Department for the Economy’s estimated maximum cost to all UK suppliers of purchasing NIROCs to meet the respective renewables obligations in GB and NI from 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2019. In NIAO’s opinion this figure is also a good estimate of the maximum amount that has been received by generators of renewable electricity in Northern Ireland over the same period through the sale of NIROCs under the NIRO scheme. Of this total amount:

• £0.37 billion is the estimated maximum cost to NI electricity suppliers of purchasing NIROCs to meet the renewables obligation in NI from 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2019; and

• £0.8 billion is the estimated maximum cost to GB electricity suppliers of purchasing surplus NIROCs to contribute towards meeting the renewables obligation in GB from 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2019.

£5 billion the NIAO’s forecast of the total maximum cost to all UK suppliers of purchasing NIROCs to meet the respective renewables obligations in NI and in GB from 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2037. In NIAO’s opinion this figure is also a good estimate of the maximum total amount that has been/will be received by generators of renewable electricity in Northern Ireland over the same period through the sale of NIROCs under the NIRO scheme. Of this total amount:

- £1.25 billion is NIAO’s forecast of the maximum cost to all NI electricity suppliers of purchasing NIROCs to meet the renewables obligation in NI up to 31 March 2037; and

- £3.75 billion is NIAO’s forecast of the maximum cost to all GB electricity suppliers of purchasing surplus NIROCs to contribute towards meeting the renewables obligation in GB up to 31 March 2037.

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. The Northern Ireland Renewables Obligation scheme (the NIRO) was established on 1 April 2005 and mirrored other Renewable Obligation schemes in Great Britain (GB). The primary objective in 2005 was to incentivise renewables development and increase the proportion of electricity consumption generated from renewable sources, keeping costs to consumers at a minimum. The Northern Ireland Executive established a target to achieve 40 per cent of all electricity consumed, to be generated from renewable sources by 2020.

2. The NIRO was open to all generators of electricity from a renewable source and closed to new applicants on 31 March 2017. It provides an additional financial return, by issuing a fixed number of Renewable Obligation Certificates (ROCs) for every megawatt hour (MWh) of electricity generated. ROCs are then traded in a single UK-wide market and purchased by UK electricity suppliers. Once a generator became accredited to the scheme they were entitled to claim ROCs for 20 years.

3. The NIRO does not involve any taxpayers’ money being paid directly from Government to investors. Instead, the Government imposes an obligation on licensed electricity suppliers to provide evidence (in the form of ROCs) that a proportion of their electricity is generated from renewable sources, or else face a financial penalty. This provides ROCs with a base monetary value prior to being traded and purchased by the electricity suppliers, as evidence that they have met their renewables obligation. Ultimately the cost of all ROCs, irrespective of origin, is passed on by electricity suppliers to UK consumers as part of their electricity bills.

4. The NIRO has been successful in achieving its aim of promoting investment in, and the generation of, renewable electricity. From virtually a standing start in 2005, electricity consumption from renewable sources reached almost 47 per cent for the 12 month period ended 31 March 2020, and the 40 per cent target by 2020 was exceeded in 2019. The Department for the Economy’s (DfE) view is that without the incentive provided by the NIRO this would not have been possible and that investment in emerging renewable technologies would have occurred at a much slower rate.

5. This report does not criticise the use of renewable sources as a means of electricity generation. There is undoubtedly a significant benefit to the environment and society, by reducing high dependence on fossil fuels, and there is evidence that the availability of renewable electricity can help control overall electricity price levels.

6. However, we identified a significant risk that some investors may be achieving a higher financial return than was required to encourage adoption of the various supported technologies. We also identified that the speed of uptake, (particularly in the two years leading up to the closure of the NIRO) has created significant additional environmental and planning impacts, which could have been avoided had there been better joined up thinking across government.

Background

7. Understanding renewable electricity generation, and how it is publically incentivised, is important as it impacts on the economy, the environment and the security of our future energy supply. In addition, recent high profile concerns relating to the Renewable Heat Incentive scheme (RHI) has led to significantly reduced public confidence in renewable energy schemes, even though the funding model is different, with RHI support paid by tax payers, whilst NIRO support is paid by electricity consumers.

8. Multiple concerns relating to the NIRO have been raised by politicians and members of the public. For example, in 2017 an anonymous letter was sent to the DfE, the Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG) and a number of other parties, setting out serious concerns about the possibility of around 300 small-scale wind turbines, without a grid connection, rushing to join the NIRO. It was alleged that their intention was to claim ROCs without any use of the electricity generated.

9. In late 2018, the media reported the potential existence of a number of ‘phantom plants’. This term related to alleged generating stations in receipt of ROCs, fuelled by biogas produced from Anaerobic Digester (AD) plants (hereafter referred to as AD based generating stations), which did not appear to physically exist. The media also reported important environmental concerns relating to AD plants. At the same time an increasing number of other public concerns were raised with us in relation to planning and environmental matters regarding certain wind turbines and AD plants.

10. Finally, concerns emerged that the level of financial support available for AD based generators in Northern Ireland (NI) was higher than in GB, and that this was attracting GB investment funds. In some cases there were allegations that the pursuit of quick returns on renewable investment could be having negative impacts on the environment. In light of all of this interest the C&AG decided that this was an important subject area to examine and report on.

11. Due to the greater number of concerns raised, the main focus of this report is therefore on small-scale, standalone on-shore wind turbines, AD plants and small scale AD based generating stations. Whilst the bulk of electricity from renewable sources in NI is generated from wind farms, with multiple turbines, these have not generated the same level of public concern.

Key Findings

There have been periods where the financial support from NIRO for small-scale wind and AD based generators in NI has been both higher and lower than the total support available in GB, although in recent periods it has tended to be higher. In addition, because of a lower renewables obligation level NI suppliers (and ultimately consumers) pay significantly less than GB counterparts to support renewable electricity

12. Energy is a devolved matter in NI and therefore policy can and will differ across devolved administrations. Until 2011, NI’s strategic approach and level of financial support to promote renewable electricity generation was broadly in line with GB. However, since then there has been a divergence in the approach towards achieving respective targets. One of the outcomes of this is higher levels of support in NI for investors in small-scale wind (from 2014 until closure in June 2016) and AD based generators (from 2011-12 until closure in 2017). Higher levels of support in GB, for the same technologies, were available before these dates.

13. The full cost of supporting electricity generated from renewable sources via ROCs is spread across all UK electricity suppliers who purchase the ROCs in order to meet a renewable obligation set annually by Government. The cost of meeting this obligation is passed on to consumers through their bills. However, the cost of supporting renewable electricity to the average NI domestic consumer is approximately one third of that paid by the average GB domestic consumer. This is because GB has a wider range of support mechanisms, including ROCs, and also because NI negotiated a lower annual supplier obligation level than GB, due to higher levels of consumer vulnerability and fuel poverty.

14. Despite lower costs passed on to NI consumers, we have found that, for small-scale wind and AD based generating stations (which generate approximately 17 per cent of renewable electricity), returns to those renewables suppliers since 2014 can be significantly higher than in GB. However, financial returns to investors in larger scale technology, who because of their size generate the largest proportion of renewable electricity, are similar to GB.

Northern Ireland has a large number of smaller standalone wind turbines which, since 2014, can achieve higher rates of return

15. The number of smaller, standalone wind turbine based generating stations increased significantly in the last few years of the NIRO. We believe that this is as a result of the higher level of financial support available to these generating stations since 2014, as well as a surge to gain accreditation prior to scheme closure. We estimated these small-scale generating stations could potentially achieve returns on investment of more than 20 per cent per annum. These small standalone wind turbines now make up approximately 94 per cent of all wind generating stations and approximately 16 per cent of potential wind generating capacity.

Accredited generating stations do not have to comply with planning or environmental rules to claim ROCs

16. We identified that the NIRO legislation (as well as the legislation supporting the two GB RO schemes) does not require generating stations to have planning permission, nor does it include a requirement to comply with environmental regulations, prior to being accredited to the NIRO. Our review identified examples of accredited wind based generating stations in receipt of ROCs, without planning permission, or which had not complied with certain conditions set out within their planning approval. We also found instances of accredited AD based generating stations in receipt of ROCs without environmental waste permits or planning permission. It is important to recognise that the primary responsibility for the enforcement of planning and environmental legislation, rests with those bodies tasked with doing this. However, in our opinion there were inherent weaknesses within the NIRO legislation, which if they had been addressed at the outset, could have helped to prevent or limit planning permission and environmental concerns.

There are separate risks in relation to off-grid and zero export generating stations, some of which are under investigation by OFGEM

17. In response to risks relating to off-grid or zero exporting generating stations and an allegation made about 300 off-grid wind turbines wasting electricity (see paragraph 8), we found that the NIRO rules with regard to permitted uses of the electricity were vague and non-specific. While we note that the NIRO legislation mirrors the legislation in GB on this matter and we were told that off-grid developments are a feature throughout the UK, we consider that this makes it difficult to determine what electricity uses were permitted, although the numbers of off-grid stations suggested in the initial allegations were greatly overstated. The DfE told us that at August 2019 there were 54 accredited generating stations (mainly wind based) which were not grid connected, or were not exporting electricity to the grid (zero-export). Since then OFGEM has conducted a programme of audits to gain assurance that these generating stations were operating lawfully and the NIRO Steering Group, which includes representatives from DfE, NIAUR and OFGEM, conducted a detailed risk assessment exercise. This concluded that electricity generated by these stations is being used in a permitted manner and that there was no evidence of wastefulness as suggested by the whistleblower.

18. However, since this conclusion, a serious issue arose, which in our opinion cast significant doubt on the reliability of one of the primary pieces of evidence used to reach it. This specifically related to thirty one ‘Independent Technical Assurance Reports’ (ITARs) submitted to OFGEM, whose independence, content and authorship were in doubt. OFGEM suspended NIROCs to the generating stations connected to these ITAR reports pending further investigation. In June 2020 OFGEM told us it had concluded that twenty two of the operators had provided alternative contemporaneous evidence to support the generating stations commissioned date and the issuing of NIROCS recommenced for these stations. The remaining nine stations continue to be under investigation by OFGEM with NIROCs suspended. However, OFGEM has told us that it was able to conclude that the information related to how the electricity was being used had already been verified by a site visit from an independent auditor appointed by them.

There were a large number of accredited generating stations which had not been assessed for rates and as a result were not subject to them

19. During our review we identified a significant number of accredited wind based and AD based generating stations which had not been assessed for rates. This has primarily arisen because neither the NIRO (nor the ROs in GB) require evidence of registration for rates as part of the accreditation process. The NIAUR told us that they assume that registration was not sought by some generators and that they are entirely supportive of the need to ensure rates are paid. However, the Energy Order places a duty of confidentiality on the NIAUR which overrides the requirement for public bodies to inform LPS in accordance with the Rates (NI) Order 1977. Based on data sets from OFGEM and LPS, we originally estimated that there was a potential annual loss of £2.1 million. Once we alerted LPS to this issue they were able to begin an exercise (using published information that NIAUR was able to direct them to) to assess the outstanding generating stations and recoup outstanding rate debts. We understand that by the end of our review significant progress had been made to address the matter and that the potential annual loss has been reduced to £0.1 million.

Financial returns for small-scale AD based generating stations appear excessive, possibly due to the limited data available to government at the time levels of support were decided

20. There has been a significant increase in the number of accredited AD based generators since 2011, when the level of ROCs was significantly increased for smaller generators following a call for evidence and consultation process. This high level of financial support for small-scale AD based generating stations, (when combined with a larger agricultural industry and the additional availability of renewable energy resources, relative to GB), has resulted in approximately three and a half times as many AD based generating stations per sq. km, compared to GB.

21. The vast majority of accredited AD based generating stations are classed as small-scale, and under the NIRO, the level of potential financial support available to these stations from 2011 onwards became increasingly higher (see Figure 13) than the level of financial support available to equivalent stations in GB under the equivalent scheme at the time.

22. The level of support provided to promote and support AD technology from 2011 was decided by the then Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (DETI), based on an adapted financial model provided by independent consultants. The model calculated the number of ROCs required based on theoretical evidence submitted to DETI through a public call for evidence.

23. We noted that much of the theoretical evidence submitted came from organisations which stood to benefit financially from any increase in the level of support at that time. We also found that the model assumed that any AD based generating stations installed would be made up of a wide range of generating outputs. In reality, the vast majority of investors commissioned AD stations with a generating capacity at the maximum permissible level of the band, offering the highest level of ROCs. This enabled investors to achieve the highest available financial return and as a result it is our opinion that these potential returns are greater than DETI had originally anticipated.

The allegation of ‘Phantom AD plants’ was not substantiated

24. The allegation of ‘phantom plants’, that is, ROCs being issued to AD based generating stations which did not in fact exist, was not found to be true as OFGEM’s investigation found that all AD based generating stations in receipt of ROCs did actually exist. The allegation may have arisen from a misinterpretation of how the NIRO operates. It is the generating station fuelled by biogas, rather than the AD plant supplying the biogas, that is accredited and a single AD plant can supply gas to more than one generating station. However, the allegations did lead to the identification of an issue of ‘gaming’ at two generating stations in close proximity, with OFGEM concluding that the stations should be accredited as one station.

Concluding remarks

25. Since 2010, the deployment of renewable generating stations proceeded at a fast pace. In our opinion the supporting governance structures and policies required to proactively identify and manage the risks associated with them should have been more robust. As the NIRO is a government scheme funded through consumers’ electricity bills, rather than by taxpayers’ funds, it is the responsibility of government, in particular the DfE, to ensure that NIRO delivers value for money.

26. The DfE has commenced a post-project evaluation exercise of the NIRO scheme, which we understand will include a value for money assessment of the scheme. As part of this exercise we believe that it will need to assess the actual rates of return to renewable electricity investors. The results of this exercise are expected later this year.

27. It is clear that the scheme has been successful in achieving its primary objective of meeting renewable electricity targets. It is also clear that the significant increase in renewable electricity generated, (which now meets almost half of Northern Ireland’s demand for electricity) has contributed to greater diversity of our electricity supplies and brings other benefits such as cleaner air and a reduction of our impact on the greenhouse effect. However, we consider that the same results might have been achieved more efficiently, at less cost and with less impact on the local natural environment.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

The Department for the Economy should take a lead role in strengthening and formalising partnership arrangements across all relevant public bodies, to ensure that any future renewable electricity or energy schemes are supported by a more proactive and joined up approach to accreditation, monitoring and enforcement.

Recommendation 2

In any future schemes which support electricity generated from renewable sources, the supporting legislation should be more specific about permitted uses of the electricity generated, particularly if it is not exported to the grid. It should also include a requirement to demonstrate that, if electricity usage was not being met by renewables, it would otherwise be met by electricity from fossil fuel sources.

Recommendation 3

When drafting new legislation, all Departments need to take into account the wider public interest. In particular, the need to disclose and share information between public bodies should not be prevented by confidentiality clauses within new legislation.

Recommendation 4

There is a need for a more strategic and formal approach to encourage and enable all public bodies to be more proactive in their duty to inform the District Valuer of additions, or changes, to the Non-Domestic Valuation List. This is a project that should be led by the Department of Finance.

Recommendation 5

Land and Property Services should complete their exercise to ensure that all rateable renewable generating stations are identified, assessed and that all payments due are collected.

Recommendation 6

The Department for the Economy should carry out a review of all types of renewable generators to ensure that current levels of financial support and the actual rates of return that are being achieved are compatible with the original projections and State Aid rules. Future schemes should project rates of return across a range of outputs and, in setting any bandings, should assume that investors will usually seek to maximise their returns by choosing the most favourable output within that banding.

Part One: Introduction

Electricity generated from renewable energy sources – overview and background

Renewable energy sources used to generate electricity are reducing Northern Ireland’s historical high dependency on fossil fuels, are sustainable and support the economy

1.1 Sustainable, renewable sources of energy, such as solar, wind and biogas (produced from material such as animal and food waste) are used to generate electricity, supplementing and gradually reducing society’s reliance on traditional fossil and nuclear fuels. In line with the rest of the European Union (EU), the UK government established legislation and policy to encourage and support the deployment of renewable electricity generating stations and in 2002, the ‘Renewables Obligation’ schemes were established in Great Britain (GB), with the Northern Ireland Renewables Obligation (NIRO) introduced in 2005.

1.2 Until then, Northern Ireland (NI) had depended almost entirely on importing fossil fuels, such as gas and coal, to generate electricity. This high dependency created uncertainty in terms of security of supply, exposing NI to the volatility of world energy prices. In addition, the high dependency on fossil based fuels in the energy mix created a significant carbon footprint, contributing to the problems associated with climate change.

1.3 Using renewable sources of energy, in place of fossil fuels, reduces this dependency. This in turn reduces exposure to volatile fuel prices, reduces carbon emissions, reduces wholesale electricity costs and avoids EU compliance costs. The most available local source of renewable power has been wind energy, however, there has been an increasing adoption of other renewables, such as solar and biogas.

The current rate and scale of renewable electricity generation deployment would not have been possible without government intervention and support. Until 2010, Northern Ireland’s strategic approach and level of financial support was broadly in line with the rest of the United Kingdom

1.4 Energy is a devolved matter and the NIRO’s primary objective was to incentivise renewables development and increase the proportion of electricity consumption generated from renewable sources, keeping costs to consumers at a minimum. Secondary objectives included the encouragement of small scale development. The NIRO provided financial support for a range of renewable technologies, for example on-shore wind, solar, anaerobic digestion and biomass. Cost barriers associated with newer renewable technologies meant that these could not otherwise compete with traditional technologies. The NIRO remained the main support mechanism for renewable electricity until 2017, when the scheme closed to new applicants, and is discussed in more detail in Part Two.

1.5 Following a relatively slow uptake of the NIRO, the then Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (DETI) published ‘Energy - A Strategic Framework for Northern Ireland’ in 2010. The framework established the need to move rapidly to much higher levels of renewable electricity consumption and confirmed the Executive’s target of 40 per cent renewable electricity by 2020.

1.6 Since the scheme’s introduction, it has been subject to a number of amendments (see Appendix One), the most significant being:

- the introduction of banding in 2009;

- introduction of higher banding levels for small scale wind in 2010 and AD related stations in 2011;

- the retention of subsidy levels in 2014; and

- scheme closure to new applicants for all technologies in 2017.

Initially support levels in GB were similar to NI in most cases and slightly higher or lower in others, such as small scale wind and small scale AD based technologies. From 2014 the equivalent levels of support for certain categories of small scale renewable technologies in GB began to fall significantly, making NI the most attractive UK region in which to invest in small scale wind based technologies and small scale anaerobic digestion (AD) based technologies.

1.7 The Department for the Economy (DfE) now has overall responsibility for renewable electricity policy and legislation, including the NIRO. The responsibility for its administration rests with the Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulation (NIAUR), which it fulfils through an Agency Services Agreement with the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (OFGEM).

From 2014 Northern Ireland became the most attractive UK region in which to invest in certain small scale renewable technologies

1.8 The introduction and retention of higher levels of subsidy in NI for certain small scale technologies, than in the rest of the UK, (which required separate EU State Aid approval), led to the rapid deployment of renewable electricity generators in NI in these technologies. This exceeded (relative to land size) deployment in the rest of the UK and it contributed to a large increase in the amount of electricity consumption generated from a renewable source in 2017 (see Figure 1). The NIRO was therefore successful in achieving its primary objective of attracting investment to facilitate renewable electricity generation and consumption of 40 per cent by 2020 (46.8 per cent was achieved for the 12 month period ended 31 March 2020).

1.9 The NIRO scheme closed to new applicants in 2017 following a decision by the UK Government. Between January 2017 and January 2020, the absence of a sitting Executive and Assembly prevented any legislation from being introduced to encourage and support any new investment in renewable energy. GB has two other renewable energy schemes – Feed-in Tariffs (FIT) scheme for small scale generation up to 5MW and Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme for large scale generation over 5MW. The FIT scheme closed on 31 March 2019, but the CfD scheme continues to provide ongoing support for existing and new generation. This means that NI is the only UK region without an incentivisation mechanism for large scale renewable electricity generation. A new Energy Strategy is currently being drafted by the DfE following a call for evidence in December 2019.

Source: Northern Ireland Statistical Research Agency

In 2017, concerns relating to renewable electricity began to emerge and since then the NIAO has identified further risks

1.10 In 2017, concerns relating to the operation of small- scale wind generators which were not connected to the grid (off-grid generators) were brought to the attention of the Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG) and the DfE by an anonymous source. Following this, and prompted by a NI Assembly debate on the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme, the Minister for the Economy tasked his Department with producing a risk assessment and audit plan of “other aspects of renewable energy”. This was to ensure that all potential vulnerabilities could be identified and proportionate action planned and executed to ensure that public confidence in the system was restored.

1.11 In response, the DfE established the ‘NIRO Assurance and Risk Management Steering Group’ (the Steering Group - comprising the DfE, the NIAUR and OFGEM) to identify, understand and address risks associated with the NIRO scheme. Subsequently, a number of concerns associated with possible abuse of the NIRO by some accredited generating stations fuelled by biogas produced from AD began to emerge in the media towards the end of 2018. In addition, following concerns from the Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA) and the Department for Infrastructure (DfI) that they did not have all the data required to identify operating AD plants, the DfE instigated a review of all AD plants in March 2019. This engaged the NIAUR, OFGEM, the NIEA and the DfI (with assistance from the local councils) to compile a list of all AD plants and generating stations, in order to identify the environmental and planning requirements for each one. Prior to this review there had been some informal engagement between the NIEA and the DfI, but this was the first time all of these public bodies had got together to share information and work as a single group.

Structure

1.12 We have focused our commentary on the facts relating to certain aspects of renewable electricity, the influence of the NIRO scheme and the risks and concerns that have emerged. Our commentary also provides context, considering why these risks have emerged and what central and local government bodies have done to manage them and, going forward, what could be done to prevent them arising again.

1.13 This report does not make any criticism of renewable electricity as a replacement for traditional electricity generation. The fact that NI has exceeded its target of 40 per cent of electricity consumption from renewables before 2020 is a considerable achievement. This achievement has given rise to positive impacts in several areas such as the price of electricity, jobs and reductions in emissions, which fall outside the scope of this report. However it is important to recognise that this has been achieved at a considerable financial cost and also in unforeseen impacts on the local natural environment.

1.14 The report is structured in the following way: Part Two presents a factual overview of the NIRO scheme, how it is funded and its contribution to the growth of renewable electricity generation and consumption. It also provides a summary of how renewable generators become accredited to the scheme and the overall cost of the scheme to electricity consumers.

Part Three focuses on wind technology, support for which has changed during the lifetime of the NIRO, offering higher levels of support than the rest of the UK. It also focuses on some of the key risks and concerns which have emerged. Areas looked at include:

- an explanation of wind renewable energy;

- comparison of financial support for wind technology in GB and NI;

- how NI funding bands have encouraged smaller single turbines;

- planning and environmental concerns and a lack of joined up thinking;

- off-grid and zero-export generators; and

- failure to charge rates for some wind turbines and anaerobic digesters.

Part Four focuses on the financial support to promote the uptake of anaerobic digester based technologies, which has also changed during the lifetime of the NIRO, offering higher levels of support than the rest of the United Kingdom. The chapter focuses on:

- how the biogas produced from the anaerobic digestion process can be used to generate electricity;

- investment and uptake of anaerobic digestion technology;

- the level of returns which, based on evidence in 2010, may have been too high;

- planning issues;

- lack of waste management licences at some anaerobic digester plants;

- handling of digestate waste from anaerobic digester plants; and

- concerns raised in the media relating to ‘phantom plants.’

Methodology

1.15 Our investigation has used a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to gather evidence. Our assessment of electricity from renewable energy and the NIRO, and how the direct and indirect risks associated with them have been identified and addressed, was informed by discussions with key staff at:

- Department for the Economy (DfE);

- Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulation (NIAUR);

- Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (OFGEM);

- Northern Ireland Environment Agency (NIEA);

- Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI);

- Department for Infrastructure (DfI);

- Department of Finance (DoF);

- Land Property Services (LPS); and

- local councils.

1.16 We also engaged extensively with a wide range of other third parties, including renewable electricity station operators, elected representatives, industry representatives, environmental groups and campaigners, journalists and concerned citizens. We reviewed documents from a wide range of sources and analysed published and unpublished data and other information held by the government and other private sources.

Part Two: The Northern Ireland Renewables Obligation scheme – how it is funded and its contribution to the growth of renewable electricity generation

The Northern Ireland Renewables Obligation has been the main support mechanism to encourage investment in renewable electricity and is part of a wider UK system that is ultimately paid for by all UK electricity consumers

2.1 Since 2005 the NIRO scheme has been the main support mechanism for encouraging increased renewable electricity generation in NI. In conjunction with the support mechanisms in the rest of the UK it ensures that NI contributes to UK wide targets in respect of renewable electricity and it also contributes to secondary policy objectives, such as encouraging the participation of small scale generators and greater diversification. It is part of a wider UK scheme which places a legal requirement on all licensed electricity suppliers to account for a specified and increasing proportion of their electricity (obligation levels) as having been supplied from renewable energy sources, or to pay a buy-out fee for any shortfall in fulfilling its obligation. Income from the buy-out fee is used to fund the administration of the NIRO, minimising any costs to the public purse.

2.2 Operators of accredited renewable generating stations (accredited generators) are given Renewables Obligation Certificates (ROCs) for each megawatt-hour (MWh) of eligible output. These certificates can then be traded and bought by electricity suppliers who can use them to provide evidence towards their compliance with the renewable obligation level that has been set by government.

2.3 ROCs issued in NI are tradable along with ROCs issued in England, Scotland and Wales in a UK-wide market for ROCs. Normal market forces mean that electricity suppliers will compete with each other to meet their obligation at the lowest cost possible, by sourcing competitively priced ROCs, (or by paying a buy-out fee) to fulfil their obligation. In any given year, the cost of meeting the obligation will depend on the supply of ROCs available from renewable generators and the demand for ROCs from electricity suppliers.

2.4 Unlike other renewable energy schemes in NI, for example RHI, the NIRO is not funded by taxpayers. It is part of a UK wide market-based Renewable Obligation certificate system, which is ultimately paid for by all UK electricity consumers. The overall cost to consumers (see paragraphs 2.12 - 2.16) is primarily determined by government via a number of complex mechanisms, which include setting obligation levels, the ROC buy-out price for electricity suppliers and setting the number of ROCs to be awarded to accredited generators.

2.5 The NIRO has been subject to a number of changes since its introduction (see timeline in Appendix 1) and on 31 March 2017, following a decision to close the scheme in GB, it closed to new applications. There were exceptions for applicants meeting certain criteria for grace periods, however these grace periods have now passed and the scheme is now fully closed.

Figure 2. How the NIRO works

Source: Image courtesy of OFGEM

2.6 Income from selling ROCs provides accredited generators with a relatively stable revenue stream for a period of twenty years, or until 31 March 2037, whichever is earlier. Government considered that a long term revenue stream was necessary to stimulate investment, by providing accredited generators and their investors with a sufficiently attractive return on their investment (see Part Four).

Most renewable electricity is generated by on-shore wind turbines

2.7 OFGEM is responsible for assessing applications to the scheme, with all applicants having to meet eligibility conditions and criteria to be granted accreditation. At 31 March 2019 there were 23,682 renewable generating stations accredited to the NIRO. Whilst solar stations account for approximately 94 per cent of all accredited stations, significantly outnumbering all other technologies, they are mostly micro generators, accounting for less than 7 per cent of renewable electricity generated. Most generation comes from on-shore wind turbines (85.4 per cent), with fuelled generating stations (which includes AD based generating stations) accounting for 10.6 per cent (see Figure 3). This report focuses on small scale wind and AD based renewable electricity sources.

Figure 3. Accredited renewable generating stations and generating capacity by type

|

Generating station type |

Number of stations |

% of stations |

% of renewable electricity generated in 2019-20 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Solar |

22,196 |

94 |

3.3 |

|

Wind |

1,282 |

5 |

85.4 |

|

Fuelled (includes biomass /AD biogas and landfill gas) |

126 |

<1 |

10.6 |

|

Hydro & Tidal |

86 |

<1 |

0.6 |

|

Total |

23,690 |

100 |

100.0 |

Source: The number of stations comes from OFGEM’s latest published data at 31 March 2019 and the percentage of electricity generated comes from Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency rolling 12 month data from April 2019 to March 2020.

2.8 Once accredited and operational, accredited generators submit output data to OFGEM, which is used to calculate the number of ROCs to be issued. There is a responsibility on accredited generators to submit accurate, non-fraudulent data to OFGEM. However, there are inevitably some risks associated with accrediting generating stations and issuing ROCs to generators who are motivated to maximise revenue from their assets. To manage these risks, OFGEM conducts a programme of generating station audits to verify the submitted data and information.

2.9 The objectives of these audits can be summarised as follows:

- verify generated output data submissions (based on which ROCs are issued);

- assure accreditation information is correct;

- detect fraud and non-compliance;

- deter the fraudulent or careless submission of inaccurate data; and

- detect departures from good practice.

2.10 OFGEM told us that it compares the generation data submitted to it from accredited generators against data provided by Northern Ireland Electricity Networks Limited which shows how much renewable electricity has been uploaded to the grid, and it investigates any anomalies. Based on the findings from this work, OFGEM has the power to withhold or revoke ROCs, or to revoke accreditation from a generating station. It also has a dedicated Counter Fraud team which provides fraud prevention, detection and investigation support to the NIRO.

2.11 In 2018 OFGEM also carried out an additional programme of audit and verification checks (including 100 per cent on-site audits of off-grid or zero-exporting stations) in response to allegations relating to a small number of generating stations which were at risk of gaming the system. These allegations, along with other emerging risks, are discussed in more detail in Parts Three and Four.

The cost of the NIRO and GBRO schemes are borne by all UK consumers but the lower obligation level in NI means that the impact on consumers here will be less than in GB

2.12 The costs associated with all of the RO schemes are initially paid for by UK electricity suppliers, who then pass on these costs to electricity consumers, through their electricity bills. Suppliers are obliged to source a proportion of the electricity they supply from renewable sources and to evidence that they have done so by submitting a certain number of ROCs (or a cost equivalent) as a proportion of the amount of annual electricity provided to their customers. ROCs are purchased directly from accredited generators or from a central trading market. The proportion of electricity that suppliers must source from renewables is known as the renewables obligation level and this is set in advance each year by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) for all UK regions.

2.13 At the outset of the scheme, a significantly lower annual obligation level was agreed for NI, which took into account its higher levels of consumer vulnerability, particularly as a result of higher levels of fuel poverty compared to other UK regions. In 2020-21, for example:

- NI electricity suppliers will be required to submit 0.185 ROCs for each MWh supplied; whereas

- GB electricity suppliers will be required to submit 0.471 ROCs for each MWh supplied.

2.14 Since all ROCs are tradable within a single UK-wide market, the costs associated with them are socialised, meaning they are spread across all UK electricity consumers. As a result, the lower obligation level in NI results in lower costs for NI suppliers relative to GB and ultimately lower renewable electricity costs for electricity consumers in NI. In addition to this, more ROCs are issued to NI renewable electricity generators than NI suppliers require to meet their obligation and any surplus NIROCs are purchased by GB electricity suppliers who then present them to meet their GB obligation. Our calculations indicated that approximately 75 per cent of NIROCs are purchased by GB electricity suppliers, who then pass on these costs to GB consumers.

2.15 However, the DfE and the NIAUR have told us that it is important to note that they consider this is not an additional cost to GB consumers. This is because GB suppliers are required to comply with their respective obligations regardless of the availability of NIROCs and are likely to purchase NIROCs only where doing so is the most commercially advantageous method of meeting their own obligations. They also advised that the separate renewables obligations in the devolved administrations were always intended to run as if it was one UK wide scheme, thus contributing to both local and UK national targets, with renewables locating throughout the UK where renewable resource is available and ROCs traded throughout the UK in accordance with supplier demand.

2.16 An outcome from this is a net positive transfer from GB to NI. By way of an example, in 2017-18, the total value of ROCs issued to NI generators was around £259 million, while we have estimated that the cost to NI consumers was approximately £68 million.

2.17 The annual cost of the NIRO to the average NI domestic consumer increased from approximately £18 in 2015 to almost £31 in 2019 (see Figure 4). This equates to a percentage increase from 3.5 per cent to 5.1 per cent of the total average bill. GB domestic consumers pay a higher amount as a result of having a higher obligation level. In addition, GB has another two renewable electricity schemes (FIT and CfD, which were not extended to NI – see Paragraph 1.9). For example, in 2018 the average GB domestic consumer paid just over £80 to support renewable electricity (including almost £58 relating to the ROCs scheme), compared to the average NI customer who paid almost £29 (see Figure 4).

Source: NIAUR

* Electricity costs include generation, supply and distribution costs. * VAT is applied to all costs, including the NIRO element, at a rate of 5 per cent. * Annual costs have been rounded up to the nearest £.

2.18 The lower obligation level means that NI consumers pay less for the NIRO than GB consumers pay for the RO schemes. If NI operated a separate renewable electricity scheme independent from GB, the total cost to the NI consumer to achieve the same outcomes would be significantly higher. However, we accept that if NI was not part of the overall UK scheme this would not necessarily reduce costs for GB suppliers and consumers unless the obligation level for renewables in GB was also reduced.

2.19 Due to the complexity of the scheme, including how costs are met by suppliers and what element of these costs are passed on to consumers, it is not possible to accurately estimate the consumer cost of the scheme to date, nor predict its final cost in the future. Based on the annual number of ROCs issued to accredited renewable NI generators since 2005 and the annual buy-out fee the DfE estimated that, from 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2019 the maximum cost of the NIRO scheme to all NI electricity suppliers is approximately £0.37 billion and the cost to all GB suppliers of purchasing surplus NIROCs to contribute towards compliance with the obligation level in GB would have been approximately £0.8 billion27 which represents a significant contribution to the NI economy. We estimated that over the whole life of the scheme, from 2005 to 2037, the total cost could be £5 billion, three quarters of which could be met by GB suppliers purchasing NIROCS to comply with their obligation level.

2.20 Whatever the overall cost turns out to be, it needs to be balanced against wider sustainable benefits arising from the scheme, such as the impact on wholesale electricity prices, job creation, emission reductions from reduced reliance on fossil fuels, together with the increased resilience of supply. Note: Figure 5 costs are based on an average usage of 3.1 MW p.a. to enable a direct comparison with the rest of the UK.

Source: Department for the Economy

While higher levels of NIRO financial support to a small number of small scale technology types since 2014 has contributed to achieving Northern Ireland’s renewable electricity targets, this may have been at a higher cost than was necessary. The extent of renewables investment has also contributed to a number of planning and environmental concerns

2.21 Since 2014 financial support from the NIRO for some small scale onshore wind and AD related technologies has generally been higher in NI than the rest of the UK (see Part Four). This higher level of support has attracted increased investment in the generation of renewable electricity in NI which has contributed to the achievement of the 40 per cent renewable electricity target, as well as the associated benefits to the environment and to the renewables and agriculture industries. However, the increase in investment in small-scale wind and AD based renewable electricity, particularly after the announcement of the closure of the NIRO scheme to new applicants, has contributed to a number of planning and environment related concerns which are discussed in Part Three of this report.

Part Three: Wind turbine technology together with planning, environmental and other emerging risks relating to all renewable electricity generation

Introduction to and uptake of on-shore wind turbine technology

On-shore wind generating stations provide approximately 85 per cent of all renewable electricity generated in Northern Ireland

3.1 Wind generating stations located on land (on-shore) harness the energy of moving air to generate renewable electricity using one or more wind turbines. Along with Scotland and Wales, NI has a particularly good wind resource which, when combined with financial support from the NIRO, has made the uptake of this technology popular since 2005 (see Figure 6).

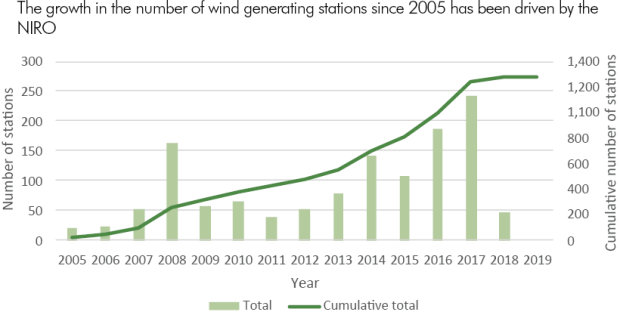

Figure 6. The number of accredited wind generating stations since 2005 in Northern Ireland

Note: OFGEM accredits single and multiple turbines grouped together and treats them as a single station. This graph shows the number of wind generating stations, rather than the number of individual turbines. The number of individual turbines is approximately 1,700. The spike in accreditations in 2008 can be attributed to the introduction of agents to the NIRO, which made the process easier and more straightforward for micro-generators to accredit to the scheme.

Source: OFGEM

3.2 Wind generating stations can range from very small-scale single, micro turbines of around 4kW, costing a few thousand pounds, to multi-MW wind farms with multiple turbine stations costing millions of pounds. While there are a number of cost factors unique to each wind generating station, for example commissioning costs, grid connection costs and groundwork costs, the range and complexity of these capital costs are much less than those associated with generating stations fuelled by biogas produced from AD. (Anaerobic Digester (AD) plants are discussed in Part Four). The day to day operating costs are also significantly less.

3.3 Being an older and more popular renewable technology than AD, more accurate financial data was available to DETI to forecast the level of financial support required to stimulate investment in wind generation and, as a result, the risk of overcompensating investors should have been significantly less than with AD.

Since 2014 a higher level of support for smaller standalone wind turbines, compared to GB, has led to a significant number of them in Northern Ireland

3.4 NI has significant numbers of smaller wind turbine generators with a capacity of less than 250kW (see Figure 7) accounting for a third of on-shore wind ROCs issued. This has been primarily driven by the higher levels of ROCs per 1MWh for the smaller generators and has led to a much larger proportion of smaller standalone wind turbines in NI than in GB; approximately three times as many by geographical area.

Figure 7. Analysis of accredited wind generating stations in Northern Ireland at 31 March 2019

|

Wind generating station generating capacity |

Number of ROCs awarded per 1MWh generated (since 2010) |

Number of accredited wind generating stations in Northern Ireland |

|---|---|---|

|

≤250 kWh |

4 |

1,209 |

|

250kWh - 5MWh |

1 |

20 |

|

>5MWh |

0.9 |

53 |

|

Total |

- |

1,282 |

Note: > than 250 and above 5MW often consist of consist of larger windfarms with up to 20 individual turbines.

Source: OFGEM

3.5 As was the case with AD technology, the divergence in government financial support for small scale wind technology between NI and the rest of the UK stimulated the successful uptake of the technology, particularly after the NIRO closure was announced.

3.6 In 2014, the DfE carried out a review of banding levels which indicated that capital costs were marginally increasing and decided therefore to maintain 2010 support levels. Apart from this review, we are not aware of any regular monitoring process which could have alerted the Department to the risk of higher (or lower) returns being made by wind generating stations, prior to the closure of the NIRO to small scale wind on 30 June 2016.

3.7 We have calculated that the ROCs paid for a typical 225kW standalone wind turbine with a 24 per cent load factor (the percentage of time the turbine generates electricity) would give an annual return in excess of 20 per cent and a payback time on the original investment of less than 4 years. Therefore, in our opinion the rate of ROCs paid for turbines with capacity less than 250kWh appears to have been excessive.

Smaller standalone wind turbines generate a relatively small amount of electricity but account for a much larger number of ROCs issued

3.8 The 2019 deployment profiles of on-shore wind generated electricity (see Figure 8) show that 84 per cent of potential wind generating capacity is provided by generators in the over 5MW band. Typically these will be large windfarms with many turbines, although for the purposes of NIRO accreditation they are categorised as single stations. As renewable electricity generated in this band only earns 0.9 ROC per MWh generated (compared to 4 ROCs per MWh generated by smaller turbines up to 250 kW), it provides better value for money to the consumer.

3.9 As an illustration, a standalone 225kW turbine accredited since March 2010, generating 473 MW of electricity in 2019, will receive 1,892 ROCs, which is worth approximately £95,000. However, the same amount of electricity produced by a same size turbine which is part of a larger windfarm will result in the issue of 426 ROCs, worth approximately £21,000.

Figure 8. Analysis of the deployment of accredited wind generating stations in Northern Ireland at 31 March 2019

|

Capacity |

Deployment percentages in 2019 |

Deployment percentages in 2014 |

Percentage change |

|---|---|---|---|

|

<5 kW |

<0.1% |

< 0.1% |

- |

|

5-50 kW |

< 1% |

1% |

- |

|

50-500 kW* |

13% |

3% |

+ 10% |

|

500-5,000 kW |

3% |

3% |

- |

|

>5,000 kW |

84% |

93% |

-9% |

* As per Figure 7 there are only 20 stations with a capacity between 250 and 500kw. 98.4 per cent of stations in this band are less than or equal too 250kW.

Source: 2019 deployment percentages calculated from OFGEM 2019 data. 2014 deployment percentages taken from “Review of RO banding for small scale renewables” – Cambridge Economic Policy Associates and Parsons Brinckerhoff, January 2014.

3.10 Figure 8 indicates that since the 2014 decision to retain higher levels of ROCs and the subsequent divergence from GB support via the FIT (see Part Four, paragraph 4.19), there has been a decrease in the percentage of capacity at the >5MWband, with a corresponding increase in capacity at the 50-500 kW band. This change in generating deployment since 2014 means that smaller standalone turbines (up to 250 kW), which are capable of generating around 13 per cent of on-shore wind generation, account for approximately 40 per cent of the total NIRO cost associated with wind generation. This compares to around 60 per cent of the cost supporting almost 87 per cent of wind generation for > 500kW.

3.11 We conclude from this that the high levels of investment in small scale wind generating stations, was driven by the potential for more favourable financial returns, when compared to the potential returns available to large scale wind generating stations. The retention of more favourable returns in 2014 combined with the announced closure of the scheme accelerated this level of investment, leading to a reduction in value for money to the electricity consumer.

Planning and environmental emerging risks

The primary responsibility for planning and environmental matters rests with the bodies tasked with doing this. However it was surprising that there was no provision in NIRO legislation to revoke accreditation or withhold ROCs from generating stations which do not meet planning or environmental requirements

3.12 Since 2015 councils have been responsible for local planning, with the DfI retaining regional oversight and planning responsibilities for larger projects of regional significance. This is often referred to as a two tier planning system. The DfI also has reserved power to take local planning enforcement action, but this is only intended to be exercised in exceptional circumstances and, to date, has not been exercised in local renewable electricity planning developments.

3.13 AD plants and wind turbines normally require planning approval which must be acquired prior to construction, and developers are required to comply with any conditions set out within the approval. Where appropriate, environmental impacts associated with the construction and operation of a generating station fuelled by biogas produced from an AD plant or wind turbine are built into the planning process.

3.14 When it was announced that the NIRO was closing on 31 March 2017, there was a large increase in applications to the scheme. In order to secure NIRO accreditation by particular dates, some developers proceeded to construct their AD plants and wind turbines without securing the necessary grant of planning permission or other consents (where this was required).

3.15 There is no requirement in the NIRO legislation for planning and environmental regulations to be complied with in order for a generating station to be accredited and receive ROCs. As a result a large number of wind turbines (and AD plants with a generating station – see Part 4) were built and started claiming ROCs despite not having planning permission. In many cases planning permission was then sought retrospectively.

3.16 The Planning Act (Northern Ireland) 2011 provides planning enforcement powers, whereby if a council considers that there has been a breach of planning control, it may take enforcement action. In determining the most appropriate course of action in response to alleged breaches of planning control, planning authorities take into account the extent of the breach and its potential impact. If a council determines that a wind turbine (or AD plant) has not complied with planning laws, either by not seeking approval before building or not following the stipulations in its planning approval, then the developer may have an opportunity to regularise the development. This can be achieved by complying with the original planning approval, by submitting a revised planning application, or if no planning application had previously been submitted, by seeking retrospective approval. Failure to do one of these can lead to the wind turbine (or AD plant) being categorised as ‘unauthorised development’ or a breach of planning control and subject to formal enforcement action, such as the service of an Enforcement Notice (EN), Stop Notice (SN) or Breach of Condition Notice (BOCN).

3.17 While an EN may ultimately prove effective in remedying a breach of planning control, it does not lead to immediate action. The combined effect of legislation and planning policies can often lead to considerable delay between the date of issue of an EN and the date on which non-compliance becomes a criminal offence. This is because the EN may be appealed and a council must wait until an appeal is heard and determined. Appendix 3 details an example of an EN being issued to an AD Plant as a result of a breach in planning regulations.

3.18 During this period, a non-compliant or unauthorised wind turbine/AD plant with a generating station will continue to earn ROCs, as there is no provision within the NIRO legislation to enable the NIAUR or OFGEM to revoke accreditation or to stop or reclaim ROCs payments made to generating stations which are not complying with planning or environmental laws. If the NIAUR or OFGEM were to attempt to withhold NIROCs due to a planning issue, it could result in a potential claim for compensation from the developer which would not only be costly, but the developer could be successful as there is no legal basis for them to do so.

3.19 Councils also have the power to issue a SN alongside an EN, which will compel an AD or wind turbine developer to cease operations. However, this must be given careful consideration, as it can result in a legal challenge and a potential claim for compensation, which can be extremely costly to a council. As a result, councils only consider issuing a SN if there is demonstrable harm to the environment as a result of the alleged breach.

3.20 There have been a number of compliance breaches associated with AD plants and wind turbines. Most breaches are deemed minor and were usually resolved by negotiation or were not expedient to pursue. However, a small number of generating stations have had more complex or persistent concerns which have resulted in ENs (and to a lesser extent SNs) being issued. Examples ranged from breaching of specific planning conditions, through to unauthorised AD plants or wind turbines.

3.21 NIAUR and OFGEM told us that they have no vires in respect of AD plants or related planning matters and therefore they place full reliance on councils and DfI to ensure that both AD plants (which supply biogas to AD based generating stations) and wind turbines have appropriate planning approval and that this is enforced in accordance with the requirements of planning legislation.

3.22 We noted that in renewable developments with more than one occurrence of non-compliance, or with a history of non-compliance, follow-up checks are not performed by councils. We understand that the onus is on developers to satisfy themselves that the development on site has been carried out in accordance with the approval and that council planning staff do not have the resources to check, or follow up, on all non-compliance matters. As with all other areas of planning, reliance is placed on members of the public or other third parties to bring potential matters of non-compliance to a council’s attention.

3.23 To date, two councils have each issued a single SN to wind turbine developments. No generating stations fuelled by biogas produced from AD have been issued with a SN. Even when a SN is issued to a generator, its developers would still be entitled to all ROCs earned (and previous ROCs earned) up to the point at which operations ceased, even if the plant is found to have operated illegally.

The NIRO legislation did not take account of planning and environmental risks. Engagement with other agencies and departments at an earlier stage would likely have supported greater joined up thinking in the design of the scheme

3.24 In our opinion, a small number of AD and wind turbine developers appear to have taken advantage of a number of regulatory systems which:

- were not designed from the outset to identify and manage the complexities and risks of renewable technology development;

- faced a surge in applications for planning, waste management licences (WML) and accreditation to the NIRO, which was not entirely forecast;

- are reliant on self-compliance by developers;

- were not operating in partnership from the outset of the NIRO scheme; and

- lacked adequate, joined-up sanctions to deal with non-compliance.

3.25 The concerns in relation to the NIRO could have been avoided if:

- formal partnership arrangements had been in place between all public bodies connected to the NIRO, to align renewables development policies and strengthen regulatory enforcement powers, as well as sharing of information;

- the legislation had enabled NIAUR and OFGEM complementary enforcement powers to withhold and revoke ROCs from AD based generating stations (using biogas from a non-compliant or unauthorised AD plant) and non-compliant or unauthorised wind turbines; and

- the legislation had enabled OFGEM to ensure that planning approval and WML were in place prior to granting accreditation to an AD based generating station (physically connected to and located with an AD plant).

Recommendation 1

The Department for the Economy should take a lead role in strengthening and formalising partnership arrangements across all relevant public bodies, to ensure that any future renewable electricity or energy schemes are supported by a more proactive and joined up approach to accreditation, monitoring and enforcement.

A small number of renewable generators are not connected to the electricity grid. This leads to a risk that electricity could be generated just to collect ROCs and used in a wasteful manner

3.26 All accredited UK RO scheme generators can claim ROCs so long as the renewable electricity generated is supplied by a licensed electricity supplier to customers or is used in a “Permitted Way”. Prior to the introduction of “Permitted Ways” in 2009, there was no scope for generators operating off-grid to claim ROCs. Since 2009, the NIRO legislation, which mirrors the RO legislation in GB, has not required an accredited generating station to be connected to the main grid. Some stations consume all electricity generated onsite or sell it to a third party via a private line and therefore would not require a grid connection.

3.27 In early 2016, OFGEM alerted NIAUR and the DfE that prospective participants were making enquiries about off-grid and zero-export stations. In such cases, operators would use the power generated for purposes such as drying wood and keeping livestock warm. Whilst there was nothing in the NIRO Order to prevent this type of usage, there was a concern regarding the lack of independent commissioning evidence. OFGEM used its powers of information request to ask prospective generators to provide an independent report attesting to the fact that the generating station had been commissioned and explaining how the power generated was being used. These reports are known as Independent Technical Assurance Reports (ITARs).

3.28 In January 2017, the C&AG and DfE received an anonymous letter setting out concerns that an estimated 300 small on-shore wind projects would rush to accredit to the NIRO prior to the closure of the scheme, for the sole purpose of claiming ROCs, with no intention of connecting to the grid, and would use electricity unnecessarily.

3.29 In response to these concerns, the Steering Group (see paragraph 1.11) carried out a desk based risk assessment exercise of the risks associated with both off-grid and zero-export stations. In addition to this exercise, OFGEM introduced additional accreditation assurances and onsite audits of all off-grid stations, to ensure that any electricity generated and used was in accordance with scheme requirements and had a genuine purpose.

3.30 As at August 2019 there were 54 ‘zero-export’ or ‘off-grid’ generating stations, which do not export any electricity to the grid. This is because either all electricity generated is consumed on site, exported to a third party, or in some cases the grid infrastructure was at full capacity and no further connections were available. The Steering Group identified 10 stations of high risk, with a further 12 warranting further consideration.

3.31 The Steering Group concluded, on the basis of its exercise and the additional audit work undertaken by OFGEM, that all stations were using electricity generated in a manner which was consistent with the provisions of the NIRO and that there was no evidence to demonstrate that any of these stations can be shown to be using the electricity generated in a deliberately wasteful manner.

3.32 Following the Steering Group’s conclusion and towards the end of our review, we became aware of an issue in relation to the authenticity and authorship of 31 of the ITAR reports which, unknown to OFGEM at the time of submission, were compiled and signed by persons other than the stated independent energy consultant. OFGEM suspended NIROCs to the generating stations connected to these ITAR reports pending further investigation. In June 2020, OFGEM concluded that the ITAR was a material piece of evidence, amongst a range of information, on which they relied upon to grant accreditation to these generating stations. However, 22 operators provided alternative contemporaneous evidence to support the generating stations commissioned date. As such NIROC issue recommenced for these stations. The remaining 9 stations continue to be under investigation by OFGEM with NIROCs suspended. If OFGEM are not satisfied that accurate and reliable information has been provided in respect of the generating stations in question, they may take further compliance action.

3.33 We understand that the Steering Group will continue to monitor off-grid and zero-export stations. We reviewed the Steering Group’s programme of work to date and are content that, together with the ongoing work, it is proportionate to the risk that remains. However, it is our opinion that the Steering Group should not place reliance on any of the ITAR reports unless their authenticity, authorship and independence can be confirmed.

Recommendation 2

In any future schemes which support electricity generated from renewable sources, the supporting legislation should be more specific about permitted uses of the electricity generated, particularly if it is not exported to the grid. It should also include a requirement to demonstrate that, if electricity usage was not being met by renewables, it would otherwise be met by electricity from fossil fuel sources.

A significant number of generating stations had not been identified for a rates assessment, however progress has been made to address the issue

3.34 All renewable generating stations over 50kW are subject to a non-domestic rates assessment to determine if they are eligible or exempt from rates. Types of exemptions include farm based generators and/or those not exporting electricity for sale to a third party. The amount of rates payable is calculated on a valuation which takes into account the income and expenditure of the generating station.

3.35 Legislation puts a duty on all public bodies to inform Land and Property Services (LPS) of any relevant information that they come across during the exercise of their functions which may require an alteration to the rates valuation list. LPS has traditionally relied on local councils’ building control teams to inform them of new properties that are subject to non-domestic rates. However, all renewable generating stations are exempt from building control and therefore in the absence of notifications from other public bodies, LPS has had to rely on alternative sources, such as notifications from generating station owners or other third parties.

3.36 We conducted a high level matching exercise of separate datasets held by OFGEM and LPS and identified a significant difference in the total number of operating accredited generating stations and the number either being charged rates, awaiting valuation, or exempt from rates (see Figure 9). Prior to this exercise LPS had been unaware of a significant number of AD based and wind generating stations and as a result these had not been assessed. This has primarily arisen because neither the NIRO nor the ROs in GB require evidence of registration for rates as part of the accreditation process. The NIAUR told us that they assume that registration for rates was not sought by some generators and that they are entirely supportive of the need to ensure rates are paid. However, the Energy Order places a duty of confidentiality on the NIAUR which overrides the requirement for public bodies to inform LPS in accordance with the Rates (NI) Order 1977.

Recommendation 3

When drafting new legislation, all Departments need to take into account the wider public interest. In particular, the need to disclose and share information between public bodies should not be prevented by confidentiality clauses within new legislation.

3.37 Once we alerted LPS to this issue, they were able to begin an exercise, with the assistance of published information that NIAUR were able to provide, to assess the outstanding generating stations and recoup outstanding rates debts. As set out below, considerable progress had been made in resolving this issue by the time this report was finalised.

Figure 9. Total number of operating accredited stations >50kW versus total number assessed by LPS

|

Generating station type |

Number of operating accredited stations |

Number charged rates by LPS |

Number of stations either awaiting valuation or exempt |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Single wind turbines |

702 |

676 (458) |

26 (1) |

|

Wind farms |

66 |

66 (66) |

1 (1) |

|

AD generating stations |

88 |

88 (41) |

0 (5) |

|

Total |

856 |

830 (565) |

27 (7) |

Source: OFGEM and LPS

Note: Numbers in brackets relate to the status at December 2019 with non-bracketed numbers indicating status at June 2020.

Recommendation 4

There is a need for a more strategic and formal approach to encourage and enable all public bodies to be more proactive in their duty to inform the District Valuer of additions, or changes, to the Non-Domestic Valuation List. This is a project that should be led by the Department of Finance.

3.38 We performed a high level calculation based on average rates paid by each generator type in 2019-20 and those generating stations which had not yet been assessed. This indicated that until we brought this information to the attention of LPS, the potential annual loss to the public purse could have been around £2.1 million. As a result of the progress made by LPS since then to assess previously unidentified generating stations, it has calculated that the potential annual loss has been significantly reduced to just under £0.1 million.

Recommendation 5

Land and Property Services should complete their exercise to ensure that all rateable renewable generating stations are identified, assessed and that all payments due are collected.

Part Four: Financial support to promote the uptake of anaerobic digester based technologies

Introduction to anaerobic digestion technology

Anaerobic digester plants produce biogas which, when combusted, can generate renewable electricity

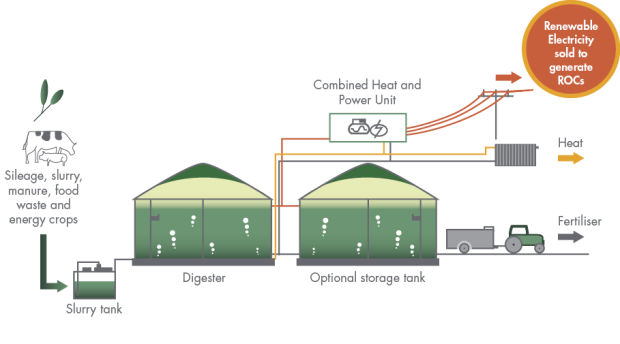

4.1 Anaerobic digestion is a natural process, involving the breakdown (digestion) of biomass (organic matter from plants and animals) by bacteria, in the absence of oxygen (anaerobic). Methane gas is produced which is collected in a membrane and combusted in a nearby combined heat and power (CHP) unit, which powers a generator, producing renewable electricity and heat.

4.2 AD plants typically use a combination of slurry, silage, energy crops, food waste and animal by-products (collectively called ‘feedstock’) which are digested in a large concrete or steel tank. This process can be managed and controlled in an anaerobic digester (AD) plant (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Example of a typical anaerobic digester plant

4.3 The CHP unit and generator are collectively referred to as a ‘generating station’ and it is this station that is accredited by OFGEM for the purposes of the NIRO scheme and not the AD plant creating the biogas.

4.4 Typically, some of the electricity generated is used on site, with the surplus sold to the grid (or over a private wire) and, together with income from ROCs awarded and sold, provides the primary income for an AD plant and/or generating station. The amount of heat produced by both the AD plant and the CHP unit is very significant and could potentially be used on-site or sold. However, in the absence of any district heating infrastructure in NI and the absence of any financial incentivisation (as is the case in GB), heat may be wasted.

4.5 The leftover material from the process, digestate, is rich in certain nutrients and can be used as a fertiliser to be spread on agricultural land. Despite its potential as a fertiliser, we found no evidence indicating that digestate had a market value. Whilst digestate, if spread correctly, is considered less hazardous to the environment than raw slurry, there are some environmental concerns in relation to the types and quantities of digestate and where it is being spread.