Executive Summary

This report highlights some of the key issues and lessons learned during the development of the Northern Ireland Food Animal Information System (NIFAIS). The NIFAIS contract was awarded in 2016 based on a nine-year term including an initial three-years to build the system. Current expectations are that the system will be complete in 2024, more than five years behind schedule and with less than a year of the contract remaining, although there are options to extend it by up to six years.

The Department has encountered several issues during the course of the development that have contributed to the delay. These give rise to lessons that can be applied to many types of public sector procurement projects.

Summary of findings

Succession planning - a strategy for replacing a computer system (or service) was not established well in advance of the expiry of current contractual arrangements. In this case it took 9 years to complete a procurement process for a business critical system upon which a £5 billion industry relies.

The Intelligent Customer - the Department should have ensured that it had the expertise to identify its own business needs and to evaluate the proposals from suppliers; and sufficient experience of the competitive dialogue procurement process.

Demonstrating commitment - The Department took decisive action on the results of the 2019 Gateway Review. This was an important factor in re-building confidence amongst the key stakeholders. However, earlier intervention at a senior level in the Department may have prevented the project from drifting into failure in the first place.

Team resources - The Project Team should have the right skills and experience to manage the project, supported by a skilled Project Management Office and dedicated User Acceptance Testing Team. For a project of this size and complex nature, staff should be allocated to it in a full-time capacity, and be independent of the day-to day operations to which it relates.

Partnership - A shared commitment and constructive co-operation was essential to advancing the project’s prospects. The Department considers that the project charter, developed jointly with the supplier, was invaluable in this regard.

Flexibility - Being prepared to stop, re-evaluate and proceed with a different approach is often overlooked in favour of pressing on with added vigour when projects don’t go to plan. In this case, flexibility proved to be key to putting NIFAIS back on track.

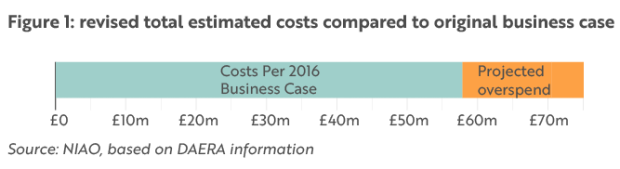

Finances - final costs are expected to be 10% higher than originally planned, albeit DAERA will have (at best) six and a half years of a fully operational system versus the twelve years expected. Although the project was managed well from a commercial cost perspective, internal costs escalated, along with the continued costs of supporting the APHIS system and the business risks this posed to the Department and its customers. The lost opportunity of utilising scarce staff time on other departmental work and the unrealised benefits of having a modern system in place for all its stakeholders, represents poor value for money.

Introduction

1. This report highlights some of the key issues and lessons learned during the development of the Northern Ireland Food Animal Information System (NIFAIS). This was designed to replace the existing Animal Public Health Information System (APHIS), a business-critical digital system in the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (the Department).

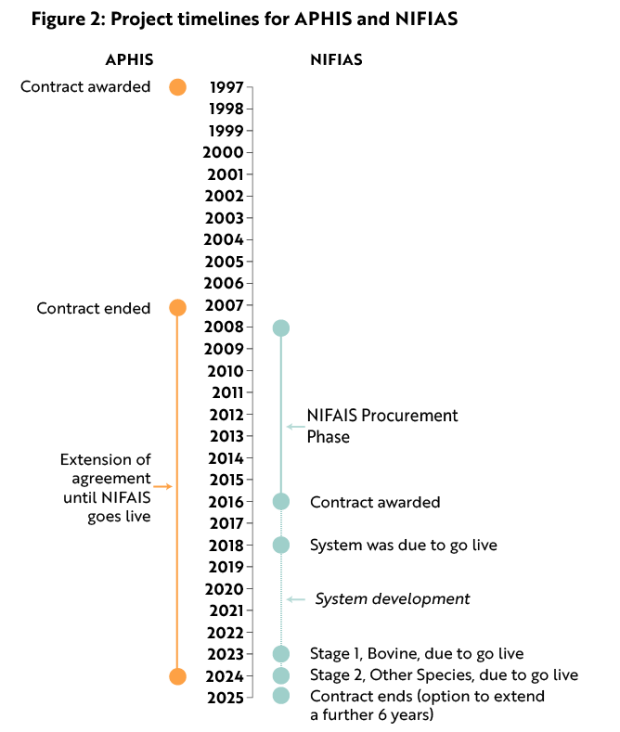

2. The APHIS contract was awarded in 1997 for an initial five-year period, subsequently extended a further 5 years. This system continues to operate, at an annual cost of approximately £0.5 million, whilst its replacement is being built. APHIS has been operating beyond its contract tenure since 2008 and cannot be switched off until NIFAIS is complete. The contract has overrun its terms by 16 years and the Department continues to rely on a technology platform that is over 20 years old.

3. The NIFAIS contract was awarded in 2016 based on a nine-year term including an initial three-years to build the system. NIFAIS was due to be operational in December 2018; however, it will not be ready until 2024, more than five years behind schedule and with less than a year of the contract remaining, although there are options to extend it by up to six years.

4. The Department encountered several issues during the course of the system’s development that have contributed to its delay. These give rise to lessons that can be applied to many types of public sector procurement projects.

Delay has presented some risks

5. The contract for the development and operation of APHIS was signed in February 1997 initially for a five-year term. Following advice from the Central Procurement Directorate (CPD), it was extended for a further five years. In 2008, CPD advised the Department to procure a new system to comply with Public Contract Regulations 2006.

6. The Department finally completed a procurement process in 2016 with a contract to build a replacement system, 9 years after the APHIS contract expired. The winning bidder was the company that built APHIS and it committed to build a new system in three years. Despite the supplier’s experience in developing and maintaining APHIS, it struggled to deliver the software and in 2020 the Department paused the project for approximately a year. After re-evaluation, the Department negotiated a revised delivery plan with the supplier and the system is planned to be completed in October 2024.

7. In the meantime, APHIS has been maintained and remains essential to the delivery of the Department’s business objectives. The APHIS system will be operating at least 16 years beyond its original 10-year term. The technology is well over 20 years old, placing the Department’s ability to deliver its operations at greater risk and significantly reduces its business efficiency.

8. The cost to the taxpayer is considerable. At the point the project was considered to have failed, the Department calculated its costs at £25.2 million. It estimated a further £50 million was needed to complete the project: a total project cost of £75 million. The revised total included £11 million of projected costs for a potential 5 year contract extension period, not covered by original business case (the original business case estimated costs of £58 million).

Scope and methodology

9. The review focused on the planning, procuring and project management of the NIFAIS project. It included:

- reviewing key documentation on strategic planning for the replacement for APHIS and the associated business cases prepared;

- interviewing NIFAIS project board members, the suppliers and other key stakeholders in the procurement and decision-making process;

- examining Gateway Reviews on the project; and

- reviewing cost information prepared by the Department.

“The Animal Public Health Information System will be operating at least 16 years beyond its original 10-year term… placing the Department’s ability to deliver its operations at greater risk and significantly reduces its business efficiency.” – Northern Ireland Audit Office

Replacing APHIS and developing NIFAIS

APHIS has been a success

10. The system contains real time information on animal movements and animal health and is used by the Department’s Veterinary Service and Animal Health Group to:

- operate disease control programmes, (for example, TB, Brucellosis, Aujeszky’s Disease, etc.);

- rapidly trace movements in the event of an exotic disease outbreak, (for example, Foot and Mouth Disease, Bluetongue, etc.);

- provide public health and trade assurances for the safety of Northern Ireland meat and pork from being able to trace livestock products back to their origin;

- provide information to monitor pesticide residues in food;

- ensure cross compliance requirements are met for Single Farm Payments (SFP) purposes; and

- to demonstrate farm to fork traceability and to provide assurance to secure new export markets.

11. The system holds records for farmed species of cattle, sheep, pigs, poultry, goats and horses, as well as details of registered establishments and operators within the livestock industry in Northern Ireland. The Department and the agricultural industry are heavily reliant on APHIS to provide evidence of compliance with legislation for local agri-food businesses covering such as disease control programmes, the farm quality assurance scheme, cross-inspection information and post-mortem data from meat plants which is communicated back to producers, meat plants and veterinary surgeons.

12. However, such unique functionality took quite some time to build. The initial software development for Phase I of APHIS began in 1998, designed primarily to replace an earlier animal health system. The project included a second phase with a vision for the system to support all Veterinary Service’s major farm animal business areas. Its aim was to help the Department meet the requirements of EU legislation, the needs of agri-food industry and the needs of consumers in a more efficient manner.

13. From 2002 to 2007, Phase II was developed to add new functionality and to interface with various departmental systems. It then developed significantly further from 2007 to 2020 whilst the Department procured a replacement solution. Complexity accumulated as each application was added and built to fit into existing arrangements, including the extremely intricate business rules operated in Veterinary Services to meet legislative requirements. Overall, this development included approximately 60 major application introductions along with various upgrades and enhancements to existing functions. The result was a highly complex, convoluted software architecture.

The need for a replacement was recognised many years ago

14. In 2008 the Department was advised to procure a new animal health system in order to comply with procurement regulations. Alongside this, APHIS’ technology needed updating and was becoming increasingly costly to maintain. As well as a modern platform and streamlined design, the new system needed to interact with other NICS ICT, including the Government Gateway interface and developing mobile technology such as smartphones and tablets.

Succession planning

A strategy for replacing a computer system (or service) should be established well in advance of the expiry of current contractual arrangements. The extensions of the APHIS contract so far beyond the original terms placed the Department at higher risk of:

- business failure from its dependence on old technology;

- breach of procurement legislation; and

- increased difficulty and costs for maintaining old technology.

15. The Department prepared a Procurement Strategy Report in September 2009 which included a draft Outline Business Case. This was only finalised and formally approved by the Department of Finance in June 2011, recommending the option of a technology upgrade for APHIS. This option remained the preferred route as each Business Case was re-evaluated. The Department said that: “the delay in getting to this stage appears to have been due to the level of expenditure and the due diligence required in terms of market research, drafting and obtaining the various approvals.”

16. The aspiration was to build a system with similar functionality to APHIS on a modern platform. It should be a flexible, innovative solution that supports the efficient and effective delivery of current and future food animal information services. It should also meet the Department’s and the agri-food industry’s needs and be capable of adapting to ensure compliance with legislation, technological developments, NICS structures and standards. However, the Department’s business processes also needed to be streamlined: reviewing these before replacing APHIS would potentially have delivered a more effective system.

The procurement process was slow

17. From June 2011, the Department spent time drafting its business requirements in preparation to go to the market, performing pre-market engagement exercises, establishing a Project Board, and buying in commercial and legal expertise from the private sector to fill gaps in capability. CPD advised that the best market approach was to use a competitive dialogue process and in July 2014 the Department advertised the project in the OJEU. Prior to going to the market, it also revised the Outline Business Case.

18. The competitive dialogue process proved intensive, taking eighteen months to complete. The Department acknowledges that the loss of key staff from Veterinary Services over time led to a significant gap in understanding of APHIS’ functionality when developing its user requirements. Consequently, it did not have sufficient expertise to challenge the assumptions and proposed technical solutions put forward by the prospective supplier(s).

The Intelligent Customer

The Department accepts that more should have been done to retain and build capacity and capability in Veterinary Services to reduce the loss of knowledge over time of this critical business system. This could also have been mitigated by developing and maintaining comprehensive systems documentation.

To be an intelligent customer, the Department should have ensured that it had:

- the expertise to identify its business needs and to evaluate the proposals from the supplier(s); and

- sufficient experience of the competitive dialogue procurement process.

19. The supplier was appointed in April 2016 and was the same company that developed and maintained APHIS. The contract included a 33-month development window and a ‘go live’ date in December 2018. Development was on a modular basis, with nine sub-stages (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Project delivery

Only one sub-stage has been delivered.

|

Stages |

Species |

Sub Stage |

Deliverable |

Planned date |

Actual date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stage 1 |

Bovine only |

1.1 |

Keeper Registration and Tag Suppliers |

30 Nov 2016 |

June 2017 |

|

1.2 |

Bovine Disease and Tracing |

31 Mar 2017 |

Was due in June 2023, now postponed a number of months |

||

|

1.3 |

Valuation, Authorise Payments, AccountNI |

31 Mar 2017 |

|||

|

1.4 |

AFIB and Cross Compliance |

30 Jun 2017 |

|||

|

1.5 |

I&R and Movements |

25 Aug 2017 |

|||

|

1.6 |

Veterinary Public Health Programme and LMC |

22 Sep 2017 |

|||

|

Stage 2 |

Multi species & remaining bovine |

2.1 |

I&R, Movements, Trade and Tracing |

23 Feb 2018 |

Due October 2024 |

|

2.2 |

Disease, VPHU, Enforcements and Tracing |

28 Sep 2018 |

|||

|

2.3 |

Welfare National Plan, Residues & AFIB |

28 Sep 2018 |

Source: NIAO, based on DAERA information.

20. Difficulties in coding Stages 1.2 to 1.4 have been a particular problem. Currently, there is an agreement to complete Stage 1 as a package, and this was due to go live in June 2023, however this has now been postponed for a number of months. The planned completion date for Stage 2 is October 2024.

A Gateway Review identified several problems

21. The Gateway Project Assurance Review (PAR) in February 2019 awarded the programme a Red Delivery Confidence Assessment, which is defined by the Panel as: “Successful delivery … appears to be unachievable – without a change of approach. There are major issues on success including definition, quality, schedule, budget required and benefits delivery, which at this stage (at the date of this PAR) do not appear to be manageable or resolvable. The programme will need re-baselining and/or overall viability re-assessed within 5-6 months.”

22. Figure 4 summarises the Panel’s conclusions.

Figure 4: Gateway Review

Several issues put the project at risk.

|

Conclusion |

Evidence |

|---|---|

|

Functionality was too complex and not understood |

Only the first sub-stage was completed successfully. Coding for the next 3 sub-stages failed to pass user acceptance testing despite many attempts at fixing the issues identified. The supplier was taken over by a larger company in 2016 and in 2017 it ‘off-shored’ much of the NIFAIS software development to India. The new team was not adequately briefed and struggled to understand the complexities of the Department’s business processes and consequently the coding supplied was not fit for purpose. |

|

Good communication and collaboration broke down when serious issues arose |

The Department managed the project closely to the terms of the contract. When a rectification plan was proposed, the supplier and the Department had difficulty reaching agreement. Frustration and anxiety grew for both parties. The Gateway Review recognised that relations were badly damaged. |

|

Appropriately skilled people were not appointed to the project full-time |

The Senior Responsible Officer and Project Director were senior staff in Veterinary Services, tasked with delivering this project in addition to their normal business activities. Replacing the APHIS system is a large project, with significant complexity. It needed fulltime, dedicated staff experienced in delivering IT projects, qualified in recognised project management methodologies and well-versed in the business area requirements. |

Source: NIAO, based on Gateway Project Assurance Review

The Department responded promptly to these issues

23. The Departmental Board took the decision to change the project’s leadership. In its place, the Department assigned senior staff experienced and qualified in project management and on a fulltime basis. Other members of the team were rotated. Subsequently, the project was paused in January 2020 for re-evaluation.

24. The Department engaged the services of the Strategic Investment Board to put forward feasibility options. The 2016 Business Case was revisited, and the options appraised. The appraisal concluded that the best value for money option was to continue with the project.

25. Whilst the positive action taken is commendable, it is concerning that it took the Department so long to take decisive action. The system was due to go live by the end of 2018, but the Department’ leadership did not respond until 2020 and took another year to get the project up and running again. The appropriate governance of such a business critical function was not in place from the start of the project and risks were not escalated and responded to when delays in delivery materialised.

Demonstrating commitment

The Department took decisive action on the results of the 2019 Gateway Review. This was an important factor in re-building confidence amongst the key stakeholders. However, earlier intervention at a senior level in the Department may have prevented the project from drifting into failure in the first place.

Team resources

The Project Team should have the right skills and experience to manage the project. Formal training, such as accredited Project Management Methodologies should be a requirement for key roles.

An effective Project Team needs to have appropriate administrative support, with a skilled Project Management Office. In addition, a dedicated Test Team is needed to build expertise in User Acceptance Testing so that software performance issues can be identified at an early stage.

For a project of this size and complexity, staff should be allocated for the duration in a full-time capacity, as necessary. They should be independent of the day-to day operations to which the project relates to avoid conflicting pressures and resourcing constraints.

“The Department took decisive action on the results of the 2019 Gateway Review. This was an important factor in re-building confidence amongst the key stakeholders. However, earlier intervention… may have prevented the project from drifting into failure in the first place.” – Northern Ireland Audit Office

Recovering the NIFAIS project

Better communication and a collaborative approach put NIFAIS back on track

26. The new project team showed an important change in attitude towards the supplier, prioritising collaboration and common purpose over strict compliance with the contract terms. A project charter was compiled jointly to establish a shared vision, values and behaviours. The parties also agreed a rectification plan, including a root cause analysis of where things had gone wrong, as well as a more agile development approach which gave the Department some assurance as to the quality of the new software being produced.

27. While the delay and delivery problems made the project financially unviable, the supplier nevertheless remained committed to its success. At this point the supplier had been paid £0.7 million for the only section of the project completed, Substage 1.1 (see Figure 1). The supplier recognised the project’s importance to the agri-food sector and acknowledged its own errors in delivery to date. Perhaps most notably, it took the risk of re-writing elements of the software during the project pause from January 2020, with no assurance that the project would continue. This action provided valuable insight into business processes and how to meet the users’ business needs.

28. In getting to this point, the Department had considered all its options, including termination of the contract, financial redress and legal proceedings against the supplier. However, legal and procurement advice was that they were unlikely to be successful. It was acknowledged that the Department had itself also contributed to the project’s failure. An Implementation Plan was proposed by the supplier and agreed. It was at this point that the Department took appropriate control of the project and steered it in the right direction.

Partnership

While it is a given that the respective parties acted professionally towards each other, it was the shared commitment and constructive co-operation that proved essential to advancing the project’s prospects. The Department considers that the project charter was invaluable in this regard.

Changing the delivery model had clear benefits

29. The supplier originally adopted a ‘waterfall’ approach to developing the system, which meant building the software for each module, quality testing it and then presenting it to the customer for User Acceptance Testing (UAT). In effect, the Department did not have any input until the build was complete and UAT testing performed. It was only then that the quality issues came to light. The modular approach ultimately proved to be inappropriate due to the co-dependencies between the modules and was abandoned.

30. The rectification plan changed the delivery model to a more agile approach. This involved developing software in two-week sprints, which was then quality tested by the supplier and the Department meaning that issues were highlighted quickly. This helped to gain earlier assurance of the quality of the software being produced while reducing the Department’s risk exposure and helping to build confidence in the supplier’s delivery. Equally, the supplier benefited from timely feedback and a greater understanding of the Department’s processes and functionality requirements.

Flexibility

The Department and the supplier resisted the temptation to persist with a failed delivery model. Being prepared to stop, re-evaluate and proceed with a different approach is often overlooked in favour of pressing on with added vigour when projects don’t go to plan. In this case, flexibility proved to be key to putting NIFAIS back on track.

31. The NIFAIS project Stage 1: Bovine is currently forecast to go live sometime in the latter half of 2023, over seven years after the contract was awarded in 2016, and 15 years after the Department was advised to procure a new system in 2008. Albeit belatedly, this will be a significant achievement.

Delay comes with significant cost

32. Given the time lag from when the project was first put to the market in 2014 to when it restarted in 2021 there were developments in business processes as well as advances in technology, which had to be dealt with through contract variations. To progress the delivery of the project, the commercial impact of these changes was subject to separate negotiation with the supplier in terms of whether it met conditions already included in the contract or whether it was a new addition to be funded.

33. Although this was a potential risk in cost terms, this worked well in practice and allowed the technical team to move forward without distraction and maintain the project’s momentum. The Department and the supplier negotiated amicably and the additional commercial costs proved minor.

34. This though was one of few positive outcomes in cost terms. Total costs are expected to be in the region of £75 million, of which £22 million is contracted to the supplier. The balance relates to in-house staff costs of £36m, APHIS running costs of £12m and other costs of £4.5m. The Department calculated ‘sunk’ costs of £25 million were incurred before the project was turned around. Much of the ‘sunk’ costs did not contribute to achieving the project’s objectives and cannot be recovered.

35. Aside from financial overruns, the Department and its stakeholders lost out on receiving the benefits expected from having a modern system in place to conduct its agri-food business. There were also opportunities lost in modernising the Department’s business processes before digitalising them. It will take many more years to evolve business processes and build them into the software.

Finances

Final costs are expected to be 10% higher than originally planned, albeit DAERA will have (at best) six and a half years of a fully operation system versus the twelve years expected. Although the project was managed well from a commercial cost perspective, internal costs escalated, along with the continued costs in supporting the APHIS system and the business risks this posed to the department and its customers. The lost opportunity of utilising scarce staff time on other work and the unrealised benefits of having a modern system in place for all its stakeholders, represents poor value for money.

Appendix 1: Further reading

NAO Delivering Successful IT-Enabled Business Change: Case studies of success (2006)

Three core principles and activities to success are noted:

- Ensuring senior level engagement

- Demonstrating commitment to the change

- Prioritising the programme and project portfolio in line with business objectives

- Creating mechanisms for clear and effective decision making

- Realising the benefits

- Selling the benefits to users

- Optimising the benefits

- Winning the support of wider stakeholders

- Acting as an intelligent client

- Managing the risks of the IT solution

- Designing and managing the business change

- Building capacity and capability

- Creating constructive relationships with suppliers

NAO: Initiating Successful Projects 2011

The quality of project initiation is highly predictive of project success:

Purpose – having clarity on the overall priorities and desired outcomes;

Affordability – understanding what delivery will cost and not being over-optimistic;

Pre-commitment – having robust internal assessment and challenge to establish if the project is feasible;

Project set-up – the detailed specification, procurement, contract and incentive design; and

Delivery and variation management – maintaining delivery pressure throughout the life of the contract and flexibility to recover the integrity of the project in light of unanticipated events or significant variations from the original plan.

Audit Scotland Principles for a digital Future: Lessons Learned from Public Sector ICT Projects (May 2017)

Principles for Success:

- Comprehensive planning setting out what you want to achieve and how you will do it

- Active governance providing appropriate control and oversight

- Putting users at the heart of the project

- Clear leadership that sets the tone and culture and provides accountability

- Individual projects are set in a central framework of strategic oversight and assurance

NIAO: LandWeb Project: An Update (2019)

- For future Agreements strong contract management controls should be in place to ensure any procurement process is completed before an Agreement expires.

- Agreements should clarify the mechanisms for Value for Money and be included as contractual conditions.

From PAC Report, 2020

Contract Management must be improved to safeguard against the continuous need for contract extensions and strengthen the Department’s negotiating position

NIAO: Management of the NI Direct Strategic Partner Project – helping to deliver Digital Transformation (2020)

- Lessons must be learned for any future contracts. We recommend that all departments ensure that strong financial management controls are in place to ensure that appropriate monitoring of expenditure is embedded in management processes. To ensure this, departments managing contracts must ensure that sufficient expert resources (for example, financial management staff) are retained throughout the duration of the contract.

- Where individual contracts are used by several departments, we recommend that a central record of key financial data is maintained by the contract owner.

- DoF must consider how digital transformation can be advanced across the entire public sector. In order to maximise the benefits for citizens, services must work seamlessly across existing organisational barriers.

- We acknowledge the role of individual departments in completing PPEs to assess and learn from the success or otherwise of individual projects. We recommend that, for future contracts, the contract owners ensure that they are fully sighted on all PPEs so that they can ensure that key lessons are learned. We recommend that DoF creates a central register of lessons learned and makes this easily accessible to all public bodies embarking on transformation projects.

- While we acknowledge that much good practice guidance on contract and project management exists across the public sector, we recommend that DoF develops a short guide to assist those progressing digital transformation projects. In our view, this would help ensure adherence to best practice.

- We recommend that DoF undertakes a review of transformation activities across the Northern Ireland public sector and uses the results to ensure that future transformation is taken forward in a strategic and co-ordinated way.

- We recommend that DoF mandates that best possible re-use is made of code, components, tools, applications and data across central government to avoid duplication of effort. NI Direct should be the single portal for all digital government services. DoF should also explore opportunities for development across the local government sector.

- Given that citizens want a “tell me once approach” to services and verification, we recommend that DoF progresses work on the Mydirect portal at pace. This involves considering the concept of citizen identification and verification, exploring the option of a single identifier and exploiting use of inter-connected registers so that users do not have to re-submit data. In addition, DoF should continue to pursue opportunities for new technologies (such as Artificial Intelligence and Robotic Process Automation) for future digital transformation.

- DoF has benefited from working with the Government Digital Service in Whitehall and Estonia in relation to digital transformation. We therefore recommend that it considers creating a new partnership with a progressive government leading the way on digital transformation as an opportunity to learn and develop best practice and strategic analysis.

- We recommend that, in line with best practice, departments ensure that all business cases provide clear and robust baselines in terms of staff and resource costs along with realisation savings targets. This involves disclosing the unit cost of the existing provision so that actual savings realised can be calculated accurately.

NAO: The Challenges in implementing digital change (2021)

The things to get right at the outset:

- Understanding aims, ambitions, risks

- Engaging commercial partners

- Approach to legacy systems and data

- Using the right mix of capability

- Choice of delivery method

- Effective funding mechanisms

NAO Insight, Lessons Learned: Resetting major programmes (2023)

Key insights for decision-makers to help determine whether to do a reset and how to increase the chances of its success.

Assess the need for a reset as soon as possible:

- Identify as soon as possible when a reset is needed, or is being undertaken without being identified

- Assess whether a reset is the right thing to do

Develop a shared understanding of how a reset will be done

- Have a clear and shared appreciation of what the reset needs to achieve

- Ensure the right culture and behaviours exist within and beyond the reset

- Explicitly consider suppliers and delivery partners

Put in place the necessary processes and skills

- Allow enough time and space

- Be clear on the governance and processes needed to support the reset

- Identify and recruit the specific skills required