List of Abbreviations

BCS Business Consultancy Services

CAJ Committee on the Administration of Justice

CSCA Children’s Services Co-operation Act

DE Department of Education

DfC Department for Communities

DoH Department of Health

DWP Department for Work and Pensions

FSM Free School Meals

NIAO Northern Ireland Audit Office

NICS Northern Ireland Civil Service

NHS National Health Service

OBA Outcomes Based Accountability

OFMdFM Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister

PfG Programme for Government

TEO The Executive Office

ToR Terms of Reference

Key Facts

18% of NI children living in relative poverty (before housing costs)

11 – 15 years gap in healthy life expectancy between the most and least deprived area

The last Child Poverty Strategy ended in May 2022

0 specific poverty reduction targets in the 2016-22 Child Poverty Strategy

8% of children living in persistent poverty (three of the last four years)

Poor children are four times more likely to develop a mental health problem by the age of 11

£825m - £1bn estimated annual costs of child poverty

24% GSCE attainment gap for children receiving Free School Meals

Over 35,000 emergency food parcels provided for children by the Trussel Trust in NI in 2022-23

£0 ring-fenced budget for Child Poverty Strategy implementation

Executive Summary

Background

1. Around a fifth of Northern Irish children live in relative poverty, before housing costs. Growing up without enough money means that children miss out on opportunities in both the short and long term and are more likely to have poorer health, educational and wellbeing outcomes than their more well-off peers.

2. Poverty rarely has a single cause and it can be difficult to separate causes and effects, however it is clear that factors including low wages, worklessness and rising living costs are significant drivers of child poverty. Family size also has an impact, as almost half of children in relative poverty in Northern Ireland live in families where there are three or more children (based on 2019-20 figures, after housing costs). The absence of affordable childcare is a barrier to allowing parents to work and therefore providing households with more income. Northern Ireland does not currently have a childcare strategy and provides considerably less government support for childcare costs than in England, Scotland

and Wales.

3. Growing up in poverty can have a significant impact on health, education and economic outcomes. Evidence shows that the gap in attainment between children growing up in poverty and their peers starts early and lasts throughout school. By the time they reach primary school, children from low-income families are already up to a year behind middle-income children in terms of cognitive skills. The relationship between health and income levels is also well established. Research has shown that childhood poverty is linked to higher levels of infant mortality and death in early adulthood, as well as poorer mental health, obesity and chronic illness. Children growing up poor are also more likely to continue to experience poverty in adulthood, and so it is important to break the cycle at as early a stage as possible.

4. Tackling poverty is a cross cutting issue and therefore an Executive-wide responsibility. The Northern Ireland Act 1998 requires the Executive to “adopt a strategy setting out how it proposes to tackle poverty, social exclusion and patterns of deprivation based on objective need.” The Executive’s Child Poverty Strategy (the Strategy) was originally developed by the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister (OFMdFM), before being passed to the Department for Communities (the Department). The Department’s role was to monitor and report on activities contained within the Strategy and lead on presenting annual reports to the Executive for approval. The Strategy ran from 2016-20 and was then extended to May 2022, at which point it concluded.

5. Despite the prevalence and impact of child poverty in Northern Ireland, there is currently no anti-poverty strategy in place. It is proposed that child poverty will be included within a new, over-arching anti-poverty strategy. Whilst a significant amount of work has been completed preparing an early outline draft strategy, progress was slowed by the continued absence of an Executive.

Key findings

There has been little sustained improvement in child poverty levels since 2016

6. The aims of the Strategy were to reduce the number of children in poverty and reduce the impact living in poverty has on children’s lives and life chances. Despite the ambition to reduce the number of children living in poverty, no specific targets were set in terms of reduction. Since the Strategy was implemented in 2016 relative poverty levels (before housing costs) have remained relatively stable, however they fell to 18 per cent in 2021-22. Combined low income and material deprivation has fallen from 9 per cent to 7 per cent. Over the same timeframe, relative poverty levels in the UK also remained stagnant.

7. Falling poverty rates do not necessarily reflect sustained improvements in standards of living. For example, Department for Health (DoH) statistics show that gap in healthy life expectancy between the most and least deprived has not significantly changed since 2016-18 and 2020-22, standing at 12.2 years for males and 14.2 years for females. DoH also reports markedly higher rates of premature mortality in the most deprived areas and that over the last five years the inequality gap in the proportion of Primary 1 children classified as obese widened from 45 per cent to 93 per cent due to an increase in obesity rates in the most deprived areas while rates in the least deprived areas saw no notable change.

The costs of dealing with the effects of child poverty are likely to

be significant

8. Several reports have estimated the wider societal costs of child poverty. The Anti-Poverty Expert Panel’s report, which is available on the Department’s website, referenced a report showing that seven years ago the costs of child poverty in NI were estimated to be £825 million per annum, of which £420 million were the direct costs of services. This is because children growing up in poverty typically require a range of compensatory measures because of the disadvantages they face, for example more intervention from social services and greater NHS expenditure to tackle poor health. The remaining costs stem from the fact that adults who grew up in poverty tend to earn less, have a higher risk of unemployment and therefore they pay less tax over their lifetime and are more likely to need public support such as benefits.

9. Despite the very high costs of dealing with the consequences of child poverty, this report notes our concerns around a lack of preventative measures in the Child Poverty Strategy. Feedback from a number of stakeholders was that, in their view, work on prevention is often the first to be impacted by budget cuts. We consider this to be short-sighted and that there is strong argument for investing in long-term preventative measures to save public money in the future. Early intervention and reducing the number of poor children who go on to become poor adults could reduce future economic and social costs significantly.

The Child Poverty Strategy’s outcomes were not clearly supported by specific actions and interventions

10. We reviewed the annual reports on the 2016-2022 Child Poverty Strategy which included details of a vast range of interventions. The links between interventions and child poverty were not always clear and we also noted that several schemes tended to be universal, rather than directed at families experiencing poverty, and participation levels in some schemes were very low. Many of the interventions and initiatives were already being delivered by departments to address child poverty, such as Free School Meals (FSM) and SureStart, rather than having been developed specifically for the Strategy. It has therefore been difficult to assess the effectiveness of the vast range of activities outlined in the annual reports, both on reducing child poverty levels and in mitigating the impact that living in poverty has on children. Whilst poverty is a complex issue with a wide range of causes and effects, we are concerned that this very broad focus may negatively impact the assessment of the effectiveness of specific interventions and the Department’s ability to co-ordinate the approach to a new Executive anti-poverty strategy.

Accountability arrangements relating to the Child Poverty Strategy were not understood by all

11. The Department’s role on the Child Poverty Strategy was to co-ordinate monitoring and reporting activities and lead on presenting the annual reports to the Executive for approval. Child poverty is an Executive-wide policy issue and while overall policy decisions rest with the Executive, delivery of specific actions within the strategy are a matter for individual departments. We found that while the Strategy set out specific delivery responsibilities for other departments and they provided annual updates to the Department on progress against these, accountability and ownership mechanisms for the Strategy were not clearly understood by all.

12. If accountability mechanisms are not understood by all stakeholders, this has the potential to hamper progress in reducing child poverty levels. Whilst we acknowledge the cross-cutting nature of social inclusion strategies, it is essential that roles and responsibilities are clearly understood by all departments with delivery roles.

A lack of joined-up working has hampered the effectiveness of the Child Poverty Strategy

13. Whilst the Child Poverty Strategy was a cross-departmental Executive strategy, we heard feedback from many stakeholders, including departmental officials involved in strategic delivery, that departments often did not work together to deliver interventions.

14. Siloed working can lead to siloed interventions and ultimately to poorer outcomes. Children experiencing poverty interact with multiple services, across both the statutory and voluntary and community sectors, therefore effective partnership working is key to improving outcomes. It is essential that NI Civil Service (NICS) departments work together in a meaningful way to develop and deliver interventions and continue to foster relationships with non-governmental organisations to share information and best practice.

There are limitations with data and measures used to assess and monitor child poverty

15. The annual report on the progress of the Child Poverty Strategy described measures taken by all departments in accordance with the Strategy and how those measures contributed to the Strategy’s aims. In most years the Annual Report was formally presented to the Executive for approval. However, the absence of a functioning Executive meant that this could not happen and the final report, covering 2021-22, was delayed until October 2023, over two years since the previous report. The 2021-22 report provided data available up to the end of March 2022 for each of the strategic indicators. However, time lags in the data meant that many of the figures presented related to earlier years. The impact of Covid-19 also meant that child poverty statistics for 2020-21 were not available. Some of the information contained within the final report is therefore out of date and incomplete in some areas.

16. There are concerns that single, narrow measures of child poverty are not necessarily the most useful or aligned with what most people consider being poor. The impact of the cost of living crisis has not been fully reflected in the latest poverty statistics and is likely to lead to worsening poverty levels in Northern Ireland. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has recently resumed work developing an experimental measure of poverty based on the Social Metrics Commission’s work. This will account for the negative impact on people’s weekly income of inescapable costs such as childcare and the impact that disability has on people’s needs; and includes the positive impacts of being able to access liquid assets such as savings, to alleviate immediate poverty. We have recommended that the Department continues to work closely with DWP on this work and expands its monitoring to include measures of persistence and depth of poverty in Northern Ireland.

The NI Executive has committed to producing a new anti-poverty strategy, however issues have been reported with the co-design process to date

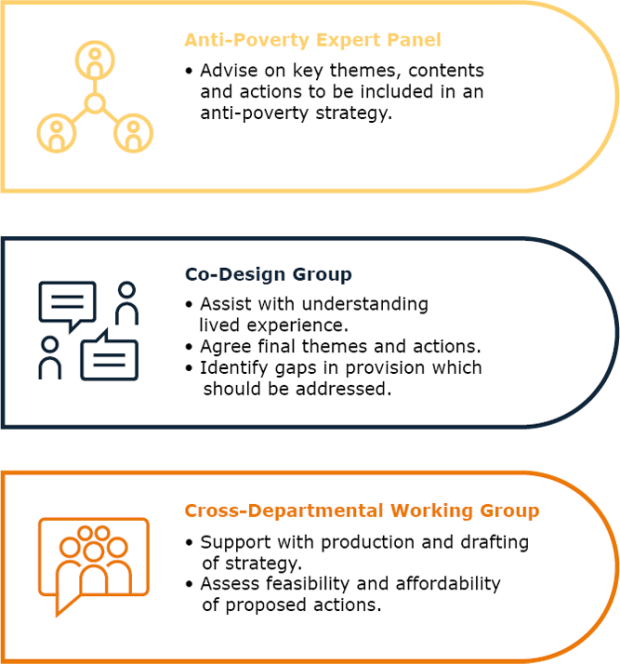

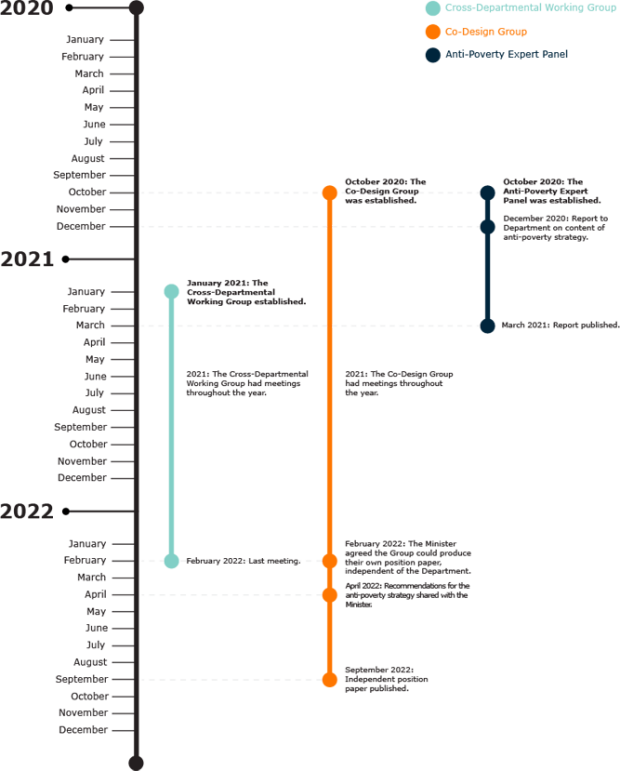

17. Under the New Decade, New Approach agreement in January 2020, the Executive agreed to develop and publish a suite of social inclusion strategies, including an anti-poverty strategy. The Executive also agreed that a co-design approach would be used to develop the strategies, led by the Department. As a result, a number of groups were established to facilitate the co-design process:

- Anti-Poverty Expert Panel – to advise on key themes, contents and actions.

- Co-Design Group – to understand lived experience, agree final themes and actions and identify gaps in provision.

- Cross-Departmental Working Group – to support with production and drafting the anti-poverty strategy and assess the feasibility and affordability of actions.

18. The new strategy presents an opportunity to learn lessons from the Child Poverty Strategy and make improvements in key areas, however we were concerned to hear that there have been issues with the co-design process, in particular in relation to the Co-Design Group. Members of the Group shared their concerns with us, including that there was a fundamental difference in understanding of the process between the Department and the Group, despite there being agreed Terms of Reference in place. As a result of concerns with the process, members of the Co-Design Group approached the Communities Minister directly and produced their own position paper, independently of departmental officials, the work on which was supported by the Department.

19. The Department also engaged consultants from the Department of Finance’s Business Consultancy Services (BCS) to review the co-design process for all of the Social Inclusion Strategies it leads on. The consultants’ findings are consistent with our discussions with stakeholders where it was evident that, by calling the process “co-design”, an expectation was set which was not met and which ultimately led to frustrations and disappointment with the outcome. The community and voluntary sector plays an important role in supporting children experiencing poverty, and it is concerning that relationships have potentially been damaged by issues in the co-design process and misunderstandings on both sides. It is essential that everyone involved learns lessons from the co-design process and that these are shared with the wider public sector in due course.

Conclusions and recommendations

20. It is important to recognise the extensive knowledge and commitment of all those we met while preparing this report, both within central government and non-governmental bodies, however the lack of progress on child poverty and the inconsistent understanding of accountability and ownership arrangements are concerning. We also heard concerns about the ongoing absence of an anti-poverty strategy and the impact this is having on the most vulnerable members of our society. The new strategy presents an important opportunity to learn lessons from the Child Poverty Strategy and to make improvements in several key areas, including accountability, monitoring and partnership working arrangements.

Recommendation 1

An integrated, cross-departmental anti-poverty strategy is urgently needed. As co-ordinating department in this area, when the Department presents a draft strategy to the Executive, it should include an action plan containing clearly defined indicators and targets aimed at quantifying and reducing poverty, including measures of persistent poverty and the poverty gap.

Recommendation 2

In developing the action plan for presentation to the Executive, as co-ordinating department, the Department should work with contributing departments to ensure that the focus is on a number of properly defined and more specific actions, including early intervention and prevention, and that they can demonstrate clear links between actions and reducing the scale and impact of poverty.

Recommendation 3

Collective ownership and accountability arrangements for the new anti-poverty strategy should be clearly outlined and agreed at the outset. The Department should provide the Executive with recommendations regarding an independent monitoring mechanism, which includes key stakeholders, to provide regular independent scrutiny and review of anti-poverty strategic outcomes as well as to identify and address gaps in understanding of the accountability process.

Recommendation 4

In leading on a new anti-poverty strategy, the Department should work with other contributing departments to identify opportunities where delivering interventions in a genuinely cross-departmental way (including the role to be played by non-governmental organisations) would be appropriate and effective, and present these proposals to the Executive for consideration.

Recommendation 5

When the new anti-poverty strategy and action plan is prepared, the Department should work with contributing departments to ensure that, as far as possible, actions included are properly costed to allow the Executive to make decisions on the budget allocations required. To enhance transparency and allow an assessment of the value delivered by publicly funded services, direct spending on new actions within the strategy should be monitored and reported.

Recommendation 6

The Department should present proposals to the Executive for monitoring mechanisms to measure the new anti-poverty strategy’s objectives and outcomes and to enable data to be collated and reported in a timely fashion.

Recommendation 7

The Department should continue to work closely with DWP on their work on developing a new poverty metric to enable it to determine whether a more nuanced poverty measure should be developed and implemented for Northern Ireland.

Recommendation 8

The Department should continue to review lessons learned from the co-design experience, and share the Co-Design Guide with other NICS departments. The Department should also share lessons learned from the co-design process with the wider public sector in due course.

Part One: Introduction and background

A significant number of children in Northern Ireland experience poverty

1.1 Around one in five children in Northern Ireland lives in relative poverty, before housing costs. Growing up without enough money means that children miss out on opportunities in both the short and long term and are more likely to have poorer health, educational and wellbeing outcomes than their more well-off peers.

1.2 There is no single definition of poverty, however it generally means not having enough resources to meet basic needs, after the cost of living is considered. The most common ways of measuring poverty are based on income, however there are other methods, for example material deprivation, which considers whether people can afford certain items, services or activities that are deemed essential. The most commonly used poverty measures are set out below, including those used by the Department (relative and absolute poverty). Poverty can be measured before or after housing costs are deducted.

Figure 1: Measurement of poverty

Relative poverty

People are considered to be living in relative income poverty if the income of their household is less than 60 per cent of the UK median household income in the current

year. This is a measure of whether those in the lowest income households are keeping

pace with the growth of incomes in the population as a whole. This measure does not reflect the significant cost of living increases that many households are currently facing.

Absolute poverty

People are considered to be in absolute income poverty if the income of their household is less than 60 per cent of the UK median household income for 2010-11, adjusted year on year for inflation. This is a measure of whether those in the lowest income households are seeing their incomes rise in real terms. Rises in the costs of living are reflected in this measure.

Combined low income and material deprivation

This is a measure of the proportion of children living in low-income households (less

than 70 per cent of the current median) that cannot afford basic goods and activities that society considers essential at a given point in time, such as a warm winter coat or going on a school trip. This measure provides an insight into children’s living standards that is not solely based on income. Rises in costs of living are reflected in this measure.

Persistent poverty

The most common definition of persistent poverty is when a family experiences relative income poverty for at least three years out of four. Rises in the cost of living are not reflected in this measure. Persistent poverty is not currently published in Northern

Ireland, however statistics are available from DWP.

1.3 Poverty rarely has a single cause but is a consequence of a range of factors including rising living costs, low pay, lack of work and inadequate social security benefits. In 2014, a DWP review found that parental worklessness and low earnings were key factors driving child poverty. It also found that childhood poverty increases the risk of poverty in adulthood, because of its link to educational attainment.

The Child Poverty Strategy ended in 2022 and so Northern Ireland does not currently have a child poverty strategy or an anti-poverty strategy

1.4 There is a statutory obligation within Section 28E of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 for the NI Executive to “adopt a strategy setting out how it proposes to tackle poverty, social exclusion and patterns of deprivation based on objective need.” Unlike other regions in the UK, Northern Ireland does not have an anti-poverty strategy in place. In June 2015, following a judicial review taken by the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ), the High Court ruled that the NI Executive had acted unlawfully in failing to adopt a strategy to tackle poverty, social inclusion and patterns of deprivation on the basis of objective need. More than eight years later, Northern Ireland still has no anti-poverty strategy. The Department told us that the lack of a local Assembly and Ministers for approximately half of this time period had severely limited the ability to develop an anti-poverty strategy.

1.5 Tackling deprivation and disadvantage is a theme that runs throughout the Draft Programme for Government (PfG) Outcomes 2016-21. Outcome 12 states that “we give our children and young people the best start in life”. The Executive published its last Child Poverty Strategy (the Strategy) in March 2016, setting out its vision to eradicate child poverty in the future. The aims of the Strategy were to reduce the number of children in poverty and reduce the impact living in poverty has on children’s lives and life chances. The Strategy set out the Executive’s goals to ensure programmes and policies provided extra support for children in poverty, improved outcomes for children in low-income families and took children out of poverty. Despite the ambition to reduce the number of children living in poverty, no specific targets were set in terms of reduction.

1.6 Progress on the Strategy and Action Plan was reported annually, with the last report covering the 2021-22 financial year. The Department took the lead on this, and poverty policy development.

1.7 In March 2020, the legislative requirement to have a standalone child poverty strategy lapsed, however, the Executive agreed to extend the Strategy to May 2022, at which point it concluded. It is proposed that, subject to the agreement of the Minister and Executive, child poverty will be subsumed into a new, overarching anti-poverty strategy.

Work on developing an anti-poverty strategy is ongoing

1.8 Delivering a fair and compassionate society that supports families and the most vulnerable in society was a key priority of the New Decade, New Approach deal published in January 2020 and the Executive has committed to developing and implementing an

anti-poverty strategy.

1.9 The then Communities Minister appointed an Anti-Poverty Expert Panel in October 2020, and tasked it with preparing key recommendations on the themes and actions an anti-poverty strategy should include. The Panel delivered its extensive report, including over 100 recommendations, in December 2020 which the Department published in March 2021. The Panel recommended that the Assembly passes an Anti-Poverty Act which includes a duty to reduce child poverty, setting targets and timetables for 2030 and beyond. The Panel also advocated for a new, non-taxable weekly Child Payment for all 0–4-year-olds and for 5–15-year-olds who are in receipt of Free School Meals. The Panel estimated that this would cost between £122 and £146 million per year. A similar scheme exists in Scotland, where families getting certain benefits receive £20 per week for every child under the age of six.

1.10 In December 2020, the Department established an Anti-Poverty Co-Design Group whose purpose was to advise it on the development and drafting of a new anti-poverty strategy. The Co-Design Group comprises members from 27 voluntary and community and advisory organisations with a presence in NI that represent the breadth of work in the sector. We met with several Co-Design Group members who expressed concerns about the process and development of a draft strategy (see Part Five). Members of the group have subsequently published their own recommendations, independent of the Department.

1.11 Work on drafting the anti-poverty strategy is ongoing, and an early outline draft representing work to date on the Strategy was presented to the previous Communities Minister before she left office in October 2022.

Scope and structure

1.12 This report provides an opportunity to review the effectiveness of the 2016-2022 Child Poverty Strategy, assessing progress against the four high-level strategy outcomes and considering the potential impacts of not achieving these, both economically and socially. The report considers both achievements and limitations of the Child Poverty Strategy and is structured as follows:

- Part Two outlines the scale of child poverty in Northern Ireland and its impact on outcomes for children;

- Part Three details delivery of the Child Poverty Strategy 2016-2022 and progress towards the four main strategic outcomes;

- Part Four considers some of the systemic issues affecting progress on child poverty; and

- Part Five provides an overview of the ongoing development of an anti-poverty strategy for Northern Ireland.

1.13 Our methodology included review and analysis of publicly available information on child poverty levels, including the Department’s statistics as well as reports published by other bodies. We also engaged with other departments, stakeholders and third sector organisations involved in this area.

Part Two: Scale and impact of child poverty in Northern Ireland

Child poverty levels have scarcely changed since 2016

2.1 The latest available data shows that overall poverty levels in Northern Ireland are amongst the lowest in the UK. Headline poverty levels in Northern Ireland fell in the decade before the Covid-19 pandemic, as income and employment rates rose, coupled with the relative affordability of housing in Northern Ireland.

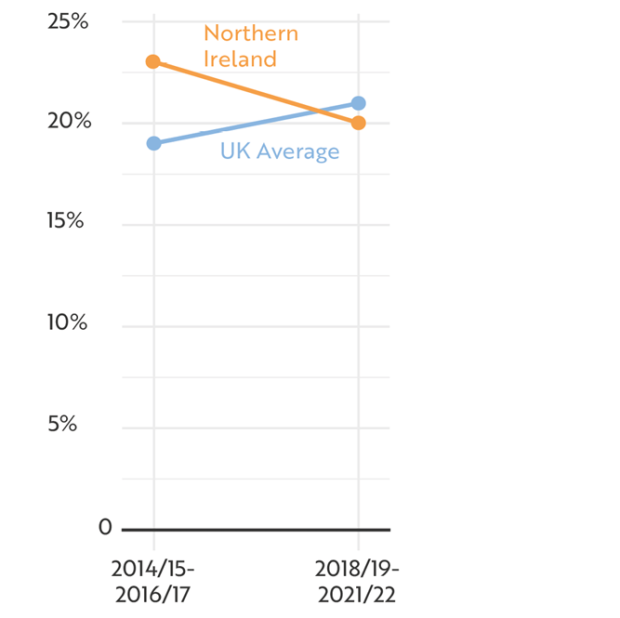

Figure 2: Children living in relative poverty, before housing costs

Source: DWP Households Below Average Income/DfC NI Poverty and Income Inequality Reports

2.2 Relative poverty is the most commonly used measure to report on child poverty levels. The statistics available since 2016 show that relative child poverty levels have changed very little since the Child Poverty Strategy was implemented. Data collection in 2020-21 was impacted by Covid-19 restrictions, leading to uncertainty around estimates and so child poverty statistics are not available for this period. The impact of the ongoing cost of living crisis is not reflected in the latest available statistics, which cover the period to 2021-22.

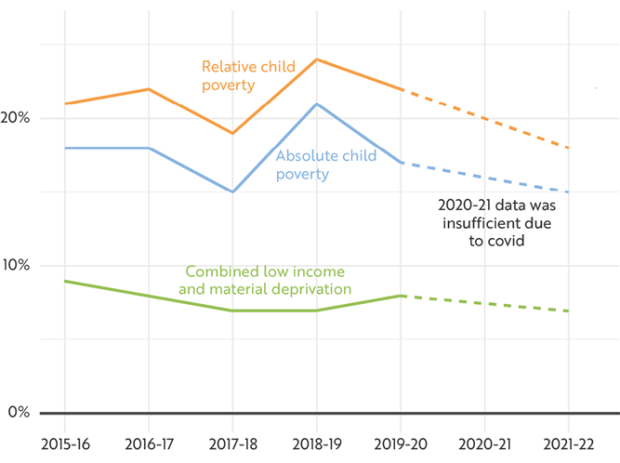

Figure 3: Headline child poverty figures, before housing costs, have changed very little since 2016

Source: DfC Child Poverty Annual Report 2021-22

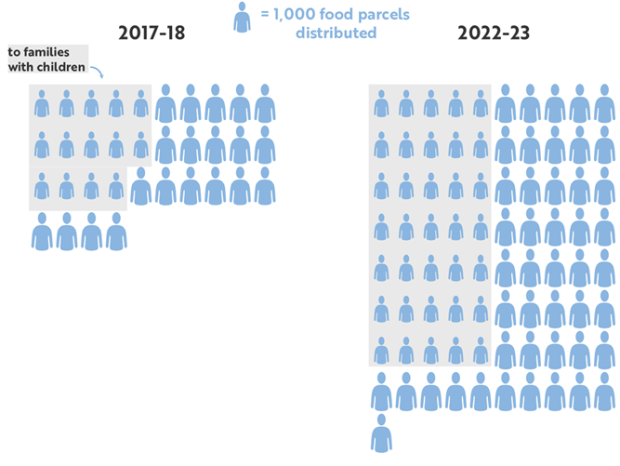

2.3 Falling poverty rates do not necessarily reflect significant improvements in standards of living. The most recent statistics released by the Trussell Trust show that the number of food parcels distributed in Northern Ireland has more than doubled in five years. The amount distributed in 2022-23 was greater than that during the pandemic, and an increase of almost 30 per cent since the prior year. Over 35,000 food parcels were provided for children in 2022-23. The Trussell Trust also highlights that foodbanks in Northern Ireland have seen the greatest long-term increase in need of any region and that one-fifth of those using foodbanks are from a working household.

Figure 4: The number of food parcels distributed by The Trussel Trust within Northern Ireland, including to families with children, has more than doubled in 5 years

Note 1: There are other food banks operational in Northern Ireland, and so, these figures do not reflect the total demand on food banks in either year.

Source: The Trussel Trust, Emergency food parcel distribution in Northern Ireland: April 2022 - March 2023

Persistent poverty levels were not routinely reported in Northern Ireland child poverty publications

2.4 Persistent poverty is defined as experiencing relative poverty for three years within a four year period. The effects of persistent poverty are more severe than short-term instances of poverty and can lead to longer-term health and wellbeing impacts. The longer that children live in poverty, the longer they go without essential items such as food, heating and clothing. Despite data being available from DWP in its Income Dynamics publication, levels of persistent poverty were not included within the annual Child Poverty Strategy reports. The most recent DWP statistics show that 8 per cent of children in Northern Ireland experienced persistent poverty (before housing costs). Depth of poverty or the “poverty gap”, i.e. how far below the relative income poverty line people are in any year, was also not reported in the annual Child Poverty Strategy reports. The Anti-Poverty Expert Panel recommended that persistent poverty and the poverty gap should be included in a suite of measures and targets in the new anti-poverty strategy.

The causes of poverty are complex and interlinked

2.5 Poverty rarely has a single cause but is a consequence of a range of factors including rising living costs, low pay, lack of work and inadequate social security benefits. In 2014, a DWP review found that parental worklessness and low earnings were key factors driving child poverty. Whilst the unemployment rate in Northern Ireland is relatively low at just over two per cent, economic inactivity levels in Northern Ireland are amongst the highest in the UK. The inactivity rate (the proportion of people aged 16 to 64 who are not working and not seeking or available to work) in Northern Ireland is 26 per cent, compared to 21 per cent in England, 22 per cent in Scotland and 26 per cent in Wales.

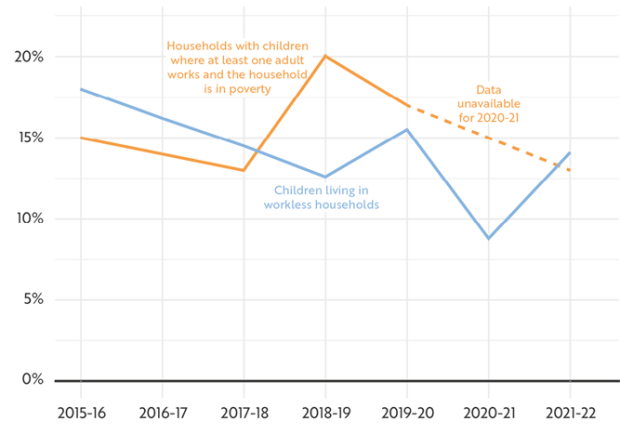

2.6 The number of children in poverty in Northern Ireland who live in a household where at least one adult works is significant. Therefore, the quality of jobs and low wages play an important role in keeping children in poverty. The Social Mobility Commission reports that qualification levels, wages, the proportion of high-paid jobs and the rate of job creation are all lower in NI than the UK average, and that one quarter of jobs here pay less than the Real Living Wage. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation reports that lone parents have the highest level of in-work poverty of all family types and are likely to face barriers such as working in a low-wage sector, working fewer hours and being restricted by access to childcare and transport.

Figure 5: Children living in working households experience poverty

Source: DfC Child Poverty Annual Report 2021-22

2.7 Families in Northern Ireland tend to be larger than those in the rest of the UK. Around 21 per cent of families in Northern Ireland have three or more children, compared to just under 15 per cent of families in the UK as a whole. It has been suggested therefore that the two-child limit, which restricts the child element of social security benefits to the first two children in a family (born after 2017), has had a disproportionate effect on families in Northern Ireland. Almost half of children in relative poverty in Northern Ireland live in families where there are three or more children (based on 2019-20 figures, after housing costs).

In the absence of a childcare strategy and affordable childcare options, many parents struggle to access work

2.8 Additional income is required to avoid poverty when there are more children, yet high costs of childcare may prevent parents of large families from working and increasing their income. We consistently heard that the absence of affordable childcare is a barrier to allowing parents to work and therefore providing households with more income. A survey by Employers for Childcare found that the average cost of a full-time childcare place in Northern Ireland is £193 per week. This is more than one third of the average NI household income in 2021-22 (before housing costs) and for low-income families this would represent an even more significant portion of their disposable income. The report states that 90 per cent of mothers and 75 per cent of fathers have changed their working arrangements due to the cost of childcare.

2.9 There is less government support for childcare costs for working families in Northern Ireland than in the rest of the UK. Northern Ireland does not provide 30 hours of free childcare for working parents of three- and four-year-olds, whereas England, Scotland and Wales do provide free childcare for these groups. Northern Ireland is also the only area of the UK not to have a childcare strategy in place, despite this being a key commitment of the New Decade, New Approach Deal agreed in January 2020.

Children living in poverty experience greater inequalities

2.10 The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child highlighted that an adequate standard of living is essential for a child’s physical and social needs and to support their development. Separating the causes and consequences of poverty is not always straightforward, especially when considered over the long term. Whilst attribution and measurement are difficult, childhood poverty is inextricably linked to other outcomes, such as health, education, and the economy. In 2021, the Department for Work and Pensions Committee in Westminster heard that child poverty is associated with increased engagement with children’s services, and poorer educational and health outcomes.

At every stage of education poorer children experience poorer outcomes

2.11 The NI Executive’s Children and Young People’s Strategy notes that “social disadvantage has the greatest single impact on educational attainment”. It also reports that by the age of three, children from low-income families have heard on average 30 million fewer words and have half the vocabulary of children in higher income families. This attainment gap widens as children get older.

2.12 Save the Children reports growing evidence across the UK and internationally that there is a strong link between poverty and cognitive outcomes in the early years. The evidence shows that the gap in attainment between children growing up in poverty and their peers starts early and lasts throughout school. By the time they reach primary school, children from low-income families are already up to a year behind middle-income children in terms of cognitive skills, while the gap between the poorest and the most advantaged tenth of children is as much as 19 months. The Child Poverty Action Group reports that children who have lived in persistent poverty during their first seven years have cognitive development scores on average 20 per cent below those of children who have never experienced poverty.

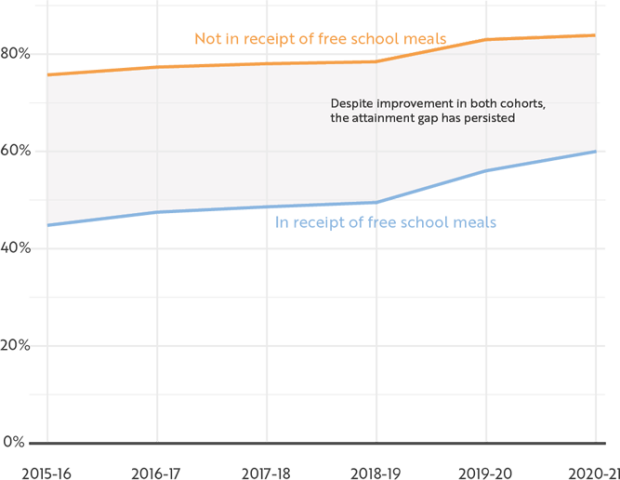

2.13 Our 2021 report on Social Deprivation and Links to Educational Attainment found that despite the significant funding provided by the Department of Education to address educational underachievement, an analysis of performance data indicates that the attainment gap between non-Free School Meals (FSM) and FSM pupils increases as they progress through compulsory education. Children receiving Free School Meals are twice as likely to leave school with no GCSEs as their more affluent peers. Whilst the proportion of children achieving five or more GCSEs at grades A* to C has generally increased, the attainment gap between pupils in receipt of FSM and other children remained relatively constant at around 30 per cent until 2021-22 when it was 24 per cent (see Figure 7).

Poverty negatively affects children’s physical and mental health

2.14 The relationship between health and income levels is well established. Research has shown that childhood poverty is linked to higher levels of infant mortality and death in early adulthood, as well as poorer mental health, obesity and chronic illness. Families living with low incomes may not be able to afford the resources needed to live a healthy lifestyle, for example healthy food, good-quality housing and sufficient heating.

2.15 The Department of Health publishes statistics on health inequalities in Northern Ireland. The most recent of these shows that in the most deprived areas, boys can expect to live

11 fewer years in ‘good’ health, and girls 15 fewer years, than children in the least

deprived areas.

2.16 The stress of living in poverty can also have an impact on both parents and children. The Millennium Cohort Study, which follows the lives of 19,000 young people born across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2000 to 2002, shows that poor children are four times more likely to develop a mental health problem by the age of 11. Their research also found that young people from more disadvantaged families, in the lowest 40 per cent of the income distribution, were twice as likely to report having attempted suicide compared to their more advantaged counterparts. The proportion experiencing psychological distress was also higher among those from lower income families.

Growing up in poverty can lead to long-term economic and social disadvantage

2.17 DWP research suggests that poverty is cyclical in nature and that children living in poverty are much more likely to become poor adults. This is because of the link between poverty and educational attainment, with higher educational attainment associated with substantially higher earnings and employment prospects in adulthood. The Anti-Poverty Expert Panel pointed to the “lifelong impact of adversity in childhood, including child poverty, and the cost of compensating for that impact” as a reason to prioritise the reduction of child poverty in Northern Ireland.

The costs of dealing with the effects of child poverty are significant

2.18 Several reports have estimated the wider societal costs of child poverty. The Child Poverty Action Group estimates that child poverty cost the UK almost £40 billion per year in 2023. Around half of this amount is because children growing up in poverty typically require a range of compensatory measures because of the disadvantages they face, for example more intervention from social services and greater NHS expenditure to tackle poor health. The remaining costs stem from the fact that adults who grew up in poverty tend to earn less, have a higher risk of unemployment and therefore they pay less tax and are more likely to need public support such as welfare benefits.

2.19 The Anti-Poverty Expert Panel, appointed by the Department, reports that five years ago the costs of child poverty in NI were estimated to be £825 million per annum, of which £420 million were the direct costs of services. A high level calculation, similar to that used by Audit Scotland in their recent briefing report on child poverty, would put the current cost of dealing with child poverty in Northern Ireland at approximately £1 billion per year. In our view, an investment in reducing child poverty has the potential to result in significant long-term savings for the public purse as well as mitigating future harms caused to children as a result of growing up in poverty. However, in Part Three of this report, we note concerns around the lack of preventative measures in the Child Poverty Strategy and feedback from a number of stakeholders that, in their view, early intervention projects are often the first to be impacted by budget cuts.

Part Three: Delivery of the Child Poverty Strategy 2016-22

The NI Executive’s Child Poverty Strategy was published in March 2016

3.1 The purpose of the Strategy was to “tackle the issues faced by children and families impacted by poverty, with the Government working collectively and in collaboration with its partners in the voluntary and community sectors and in local government”. The Strategy had two overarching aims:

- Aim 1 - Reduce the number of children in poverty; and

- Aim 2 - Reduce the impact of poverty on children.

3.2 The Strategy used an outcomes-based approach and indicators were used to measure the achievement of this work. The two official measures of child poverty (before housing costs) – absolute and relative poverty – were used to measure the achievement of Aim 1. The goal was to “turn the curve” and change the data in the right direction. No specific poverty reduction target was set.

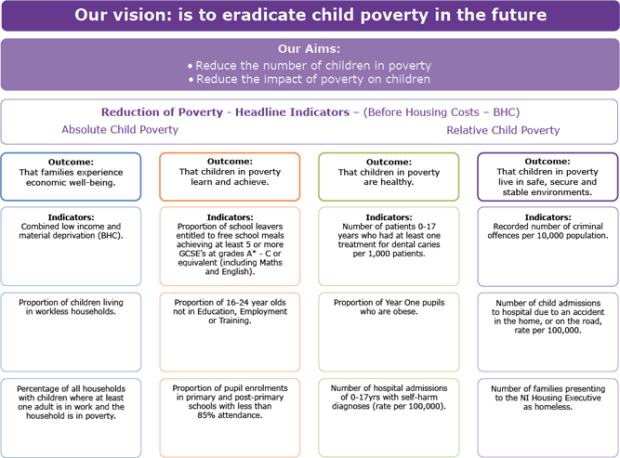

3.3 The Strategy focused on four high level outcomes:

- Families experience economic wellbeing;

- Children in poverty learn and achieve;

- Children in poverty are healthy; and

- Children in poverty live in safe, secure and stable environments.

For each outcome, three population level indicators were used to determine whether they had been achieved.

Figure 6: Extract from Executive’s Child Poverty Strategy

Source: Child Poverty Strategy 2016-2022

There was little sustained progress against most of the main poverty indicators

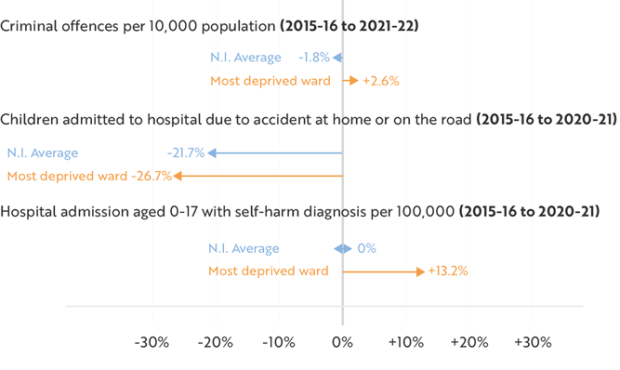

3.4 The Department produced five annual reports on progress on the Strategy, which were laid before the Assembly. The reports outlined the measures taken by departments in accordance with the Strategy and described the effects of these measures. The latest report was published in October 2023 and provided the data available at the end of March 2022, however there was a significant time lag in the data available for some poverty measures and so some of the figures presented related to the 2020-21 year. We consider issues with the quality and timeliness of the data in Part Four. The report demonstrates that there has been little sustained progress against many of the main poverty indicators. For example, Figure 3 shows that both relative and absolute poverty levels (before housing costs) and combined low income and material deprivation levels have all fluctuated around a relatively narrow band since 2015-16. In addition to this, other indicators showing little progress include those around educational attainment (Figure 7) and health and safety (Figure 8).

Figure 7: Proportion of school leavers receiving achieving more than 5 GCSE grades A*-C

Note: Figures for 2021-22 were not available in the last Child Poverty Annual Report

Source: DfC Child Poverty Annual Report 2021-22

Figure 8: A comparison of the movements in indicators between Northern Ireland average and the most deprived ward

Source: DfC Child Poverty Annual Report 2021-22

The Child Poverty Strategy did not set any specific poverty reduction targets

3.5 As noted in Part Two, the Child Poverty Strategy did not include any specific targets for child poverty levels in Northern Ireland, instead the ambition was to “turn the curve”. We heard conflicting views on the usefulness of specific targets in relation to poverty levels. Most third-party stakeholders told us that having ambitious targets focuses minds and provides a mechanism to hold organisations to account. This is supported by recent publications and research papers.

3.6 The United Nations’ Committee on the Rights of the Child recently noted concerns with the large number of children living in poverty in Great Britain and Northern Ireland and recommended that state parties develop existing policies “with clear targets, measurable indicators and robust monitoring and accountability mechanisms to end child poverty…”.

3.7 In its 2021 review of child poverty measures and targets, the DWP Committee stopped short of recommending specific targets, however it did recommend that a new child poverty strategy should include a broad set of targets including “clear, ambitious and measurable objectives and plans for reducing child poverty” and that progress on these objectives and plans should be reported annually. The Anti-Poverty Expert panel recommended that the NI Assembly should establish an Anti-Poverty Act, establishing a legal duty to reduce child poverty, including targets and timetables for 2030 and beyond.

3.8 In contrast, the Department told us that while targets may be useful, they can provide perverse incentives or unintended consequences. It added that this is a complex issue and where targets are set this must be undertaken carefully and with a view to broader, long-term outcomes. It also commented that a pure focus on raising incomes above a certain level risks pushing officials towards interventions which only raise income, while other interventions such as helping children achieve high levels of education or improve their physical and mental wellbeing may be overlooked. We were not fully convinced by this argument and consider that the 2016-22 Child Poverty Strategy indicators and outcomes were not sufficiently clear, ambitious and measurable, and that the new anti-poverty strategy presents an opportunity to rectify this. Well planned, considered targets can focus minds, improve performance and increase accountability. Regular review of targets would allow the Department to consider if they are having unintended consequences and need to be amended.

Recommendation 1

An integrated, cross-departmental anti-poverty strategy is urgently needed. As co-ordinating department in this area, when the Department presents a draft strategy to the Executive, it should include an action plan containing clearly defined indicators and targets aimed at quantifying and reducing poverty, including measures of persistent poverty and the poverty gap.

Strategic outcomes were not clearly supported by specific actions and interventions

3.9 The annual child poverty reporting focused on recording a huge range of interventions, with a short section on progress towards reducing child poverty levels. In our view, the links between individual interventions and how they impacted child poverty levels could have been made clearer. For example, the 2020-21 report included details of the following:

- Covid-19 Infection Prevention and Control Training Resource for Childcare Settings.

- DfC Summer Reading Challenge.

- DE Family Sign Language courses.

- Home Economics lessons in Healthy Eating provided to Key Stage 3 pupils.

- DoH Bee Safe scheme, teaching primary school children how to prevent accidents and dangerous situations.

We also note that these tended to be universal schemes, rather than being targeted towards children in poverty.

3.10 Participation levels in some interventions appeared low, for example:

- 171 children participated in the Cycling Proficiency Scheme.

- 174 people, all aged over 18, participated in a DfC work experience programme from 2017 to 2020.

- 12 schools delivered a “Roots of Empathy” programme of which 3 are in deprived areas.

- 45 teachers participated in a “Mindfulness in Schools” programme, 15 per cent were from schools in deprived areas.

3.11 Whilst we acknowledge that the absence of a ring-fenced budget for strategy implementation contributed to this, many interventions and initiatives aimed at addressing disadvantage were developed in advance of the creation of the Strategy. Examples include:

- Free School Meals and uniform grants.

- DE’s Careers Service for year 12s.

- SureStart – introduced in Northern Ireland in 2000-01.

- DE Extended Schools programme – launched May 2006.

- TEO’s T:BUC Uniting Communities Programme launched May 2013.

- Bright Start School Age Childcare Grant Scheme – launched March 2014.

- DfC Affordable Warmth Scheme – launched September 2014.

3.12 In fact, several departments confirmed that they would have delivered these actions regardless of the Strategy. Stakeholders also expressed some cynicism about the volume and relevance of actions recorded in the annual reports. Not everyone we spoke to was convinced that all the actions make an impact. The Department commented that an important role of a strategy can be to better co-ordinate existing initiatives and so strategies do not necessarily need to involve only new interventions. It added that often they are about continuing to deliver, develop and improve existing strategies and interventions in a co-ordinated and complementary way.

3.13 It has therefore been difficult to assess the effectiveness of the vast range of activities outlined in the annual reports, both on reducing child poverty levels and in mitigating the impact that living in poverty has on children. For annual reporting to be meaningful and useful, it should capture relevant information and clearly demonstrate the impact of specific actions on children experiencing poverty. We do not consider that the monitoring and annual reporting on the Child Poverty Strategy achieved this sufficiently. We are also concerned that this very broad focus may negatively impact the Department’s ability to assess the effectiveness of specific interventions, and to inform the approach for a new anti-poverty strategy.

There has been a lack of focus on early intervention and prevention measures

3.14 The impact of poverty is felt from a very early stage in a child’s development. Stakeholders from both central government and non-governmental organisations emphasised that prevention and early intervention are key to reducing the long-term effects of childhood poverty. However, many of the actions in the Strategy focused on improving the health and wellbeing of children already living in poverty, rather than aiming to prevent them from falling into poverty in the first place. We appreciate that health and wellbeing outcomes are important, but the ultimate aim should be to reduce the number of children experiencing poverty in the first place.

3.15 The Heckman Curve summarises research by American economist James Heckman on the long-term impact of public expenditure on early childhood education and care. It shows that the highest rate of economic return comes from investment at the earliest stages of a child’s life (from birth to age five) and argues that the best way to improve outcomes is to invest in early childhood development for disadvantaged children. Heckman’s research contends that short-term costs are offset by the long-term reduction in the need for special education and social services, better health outcomes, lower criminal justice costs and increased productivity. Officials from several departments suggested that early intervention spending is often the first to be cut in the context of the current constrained, one-year budget cycles, as it is difficult to demonstrate the immediate impact of this spending and benefits are generally seen over a much longer timeframe. In our view, this is short-sighted, and we consider that there is strong argument for investing in long-term measures to save public money in the future. Early intervention and reducing the number of poor children who go on to become poor adults could reduce future economic and social costs significantly.

Recommendation 2

In developing the action plan for presentation to the Executive, as co-ordinating Department, the Department should work with contributing departments so that the focus is on a number of properly defined and more specific actions, including early intervention and prevention, and that they can demonstrate clear links between actions and reducing the scale and impact of poverty.

Scotland appears to have the most clearly structured strategy to reduce child poverty

3.16 While it is too soon to see obvious impacts from its strategy, Scotland is perhaps the region of the UK with the clearest strategy for reducing child poverty and with the most defined targets. The Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017 sets out four specific, measurable child poverty reduction targets to be achieved by 2030, with interim targets to be met by 2023-24. The Scottish Government sets out its plans to achieve the targets in its Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan. The second of these plans, “Best Start, Bright Futures”, covers the period from 2022 to 2026 and focuses on the three main drivers of poverty: income from employment, living costs and income from social security. The delivery plan also sets a clear intention to focus actions on the families most at risk of poverty, including lone parents, larger families and young mothers.

3.17 Scotland’s delivery plan is structured into actions, their anticipated impact and the resources available to implement them. This structure makes it clear what the ambition is, how many people are likely to be impacted and what funding will be allocated to specific actions. This is in contrast with the lack of specific, tangible, costed actions in the Northern Ireland Child Poverty Strategy. Although we recognise that Scotland has more extensive powers in some areas, such as social security, we consider that the existence and structure of a delivery plan represents good practice. Scottish Government modelling also tracks progress against the child poverty targets, predicting whether these are likely to be achieved by both the interim and final target dates. This enhances accountability and focuses minds on reducing poverty as well as providing an opportunity to correct the course of action if it becomes clear that targets are unlikely to be achieved.

3.18 Further scrutiny is provided by Scotland’s Poverty and Inequality Commission which was established in July 2019. The Commission functions as an advisory non-departmental public body which provides independent advice and scrutiny to Ministers. It has specific responsibilities, set out in legislation, requiring it to provide advice to Ministers on Child Poverty Delivery Plans and monitoring progress on reducing poverty. It produces an annual Child Poverty Scrutiny Report, setting out progress towards meeting child poverty targets. Scottish Ministers must also consult the Commission as part of their annual child poverty reporting process. Whilst the Commission does not have staff or a formal budget, the Scottish Government makes resources available for its work. Commission members are appointed and accountable to Scottish Ministers and through ministers to Parliament. The Commission is supported by a panel of Experts by Experience, who have lived experience of poverty and inequality.

3.19 The Commission’s most recent report highlighted the lack of progress against key actions and the risk that the targets may not be met if current trends continue. This level of independent scrutiny draws attention to potential issues, weaknesses in delivery and gives policy makers the opportunity and impetus to respond. The Anti-Poverty Expert Panel appointed by the Department recommended a similar monitoring mechanism should be established in Northern Ireland. We have raised concerns with the current accountability and monitoring arrangements throughout this report and make a similar recommendation in Part Four.

3.20 Whilst we recognise the restrictions imposed by the Northern Ireland budget situation at present and the limitations imposed by a series of one-year budgets, we nevertheless consider that any future strategy addressing child poverty needs to be more ambitious. In particular, this should involve investment in the early years of children’s lives and the setting of clear measurable targets. The Department told us that officials regularly engage with their counterparts in Scotland to discuss progress and best practice. We would encourage the Department to continue to review best practice and benchmark progress with other jurisdictions, including a comparison of indicators and measures.

Part Four: Systemic issues affecting progress

Accountability arrangements for delivery of the Child Poverty Strategy were not understood by all

4.1 During our stakeholder engagement, we encountered different views about who was responsible for delivery of both the Strategy and a future anti-poverty strategy. In relation to the Strategy, the Department told us that its role was to co-ordinate monitoring and reporting activities from individual departments on progress against actions within the Strategy, and lead on presenting the annual reports to the Executive for approval. The Department has consistently emphasised that child poverty is an Executive-wide policy and it is not responsible for the actions or outcomes delivered by other departments. Instead, overall responsibility rests with the Executive, and delivery of specific actions is a matter for individual departments who provide annual Scorecard updates on progress. In our discussions with nominated officials from a number of contributing departments, understanding of the accountability and ownership mechanisms for the Strategy was not always clear. In our view, it is important that processes and accountability arrangements for Executive strategies are clearly understood and regularly refreshed for all involved in delivery.

4.2 The Department also emphasised that while it is responsible for leading the development of the new anti-poverty strategy, delivery of actions and outcomes will be a matter for all departments. However, it appears to us that Terms of Reference (ToR) agreed between the Department and various working groups in relation to developing the new anti-poverty strategy perpetuate confusion concerning accountability. For example, the ToR agreed with the Co-Design Group stated that “final decisions on the content of the Strategy and the actions associated with it will be the responsibility of DfC and the Minister for Communities prior to the draft Strategy being presented for public consultation and Executive agreement.” This seems to set the expectation that development of the new anti-poverty strategy and its actions are largely the Department’s responsibility, and it is perhaps not surprising that other public sector bodies would also expect the Department to therefore be accountable for outcomes. The Department accepts that the wording in the ToR could have been clearer, however it pointed out that these were considered by Co-Design Group members and discussed with officials before the Group commenced its work.

4.3 Whilst we acknowledge the cross-cutting nature of social inclusion strategies, and the need to involve all departments, it is essential that accountability arrangements are understood by all and that there are robust mechanisms in place to regularly reinforce collective responsibility and monitoring. The new anti-poverty strategy presents an opportunity to improve ownership and monitoring mechanisms.

Recommendation 3

Collective ownership and accountability arrangements for the new anti-poverty strategy should be clearly outlined and agreed at the outset. The Department should provide the Executive with recommendations regarding an independent monitoring mechanism, which includes key stakeholders, to provide regular independent scrutiny and review of anti-poverty strategic outcomes as well as to identify and address gaps in understanding of the accountability process.

An Outcomes Based Accountability approach has been poorly implemented

4.4 Outcomes Based Accountability (OBA) seeks to place the wellbeing of the population at the centre of policy and decision-making. OBA seeks to define agreed outcomes for a population and drive work towards progressing these outcomes. The OBA approach works on two levels: population accountability, which is concerned with the wellbeing of whole populations, for example the whole of Northern Ireland; and performance accountability, which looks at the wellbeing of specific sub-populations. Population outcomes are generally broad and aspirational, and progress is measured by developing and monitoring indicators over the longer term. The aim is to “turn the curve” on the indicators. The Executive recognised the difficulty of progressing population outcomes in its 2016-21 PfG consultation document and committed instead to tracking progress at a population level and using performance accountability for individual programmes and policies.

4.5 Performance accountability assesses specific interventions and measures by asking: how much did we do, how well did we do it and is anyone better off? Impacts and benefits are generally meant to be more immediate and identifiable. Under New Decade, New Approach, all parties agreed to retain an outcomes-based Programme for Government, meaning that public sector work, including the Child Poverty Strategy, should be directed at a set of agreed outcomes.

4.6 We consider that an OBA approach could have been better implemented in delivering the Child Poverty Strategy. Firstly, as noted in Part Two, the Child Poverty Strategy outcomes were not designed to prevent, eradicate or significantly improve child poverty levels, but rather sought to improve the wellbeing of children already experiencing poverty. Secondly, in our view, population level indicators set for each outcome (see Figure 6) were not clearly and directly aligned with child poverty reduction. For example, the number of children with dental cavities, self-harm hospital admissions and obesity rates in year one of primary school are used to represent children’s health. These do not necessarily demonstrate the population level outcome that children living in poverty are healthy. We therefore consider that the outcomes are too general while the indicators are too narrowly prescribed with little in the way of clear links or explanations as to how indicators demonstrate outcomes have been achieved.

A lack of joined-up working has hampered the effectiveness of the Child Poverty Strategy

4.7 The Department consistently emphasised that anti-poverty is an Executive-wide issue, and that the Child Poverty Strategy was a cross-departmental strategy, however we heard feedback from many stakeholders, including departmental officials involved in strategic delivery, that departments rarely worked together to deliver interventions. Instead, individual departments and agencies delivered their allocated actions and reported back to the Department annually.

4.8 The Children’s Services Co-operation Act 2015 (CSCA) sets out the requirement for departments and other public sector organisations to work together when developing and delivering children’s services, as well as providing the authority to share resources and pool funds for these services. However, this does not appear to be happening in practice and implementation of the CSCA has not been monitored due to the absence of an Executive. When we asked officials from various departments about the CSCA, they told us that while there is guidance setting out the contents and principles of the CSCA, it is still very difficult to implement joint services, particularly with no new funding available to do so.

4.9 A lack of joined-up working is a common finding in NIAO reports, and we are disappointed to note it once again here. In our view, siloed working leads to siloed interventions and ultimately to poorer outcomes. Children experiencing poverty interact with multiple services, across both the statutory and voluntary and community sectors, therefore effective partnership working is key to improving outcomes. It is essential that the Department works with other NICS bodies in a meaningful way to develop and deliver interventions and continues to foster relationships with non-governmental organisations to share information and best practice.

Recommendation 4

In leading on a new anti-poverty strategy the Department should work with other contributing departments to identify opportunities where delivering interventions in a genuinely cross-departmental way (including the role to be played by non-governmental organisations) would be appropriate and effective, and present these proposals to the Executive.

There are no ring-fenced budgets to deliver any of the Executive’s social inclusion strategies

4.10 Many stakeholders highlighted the lack of ring-fenced budget for Child Poverty Strategy implementation. The Department told us that this is the case for the four Executive Social Inclusions Strategies that it leads on. The Department must therefore try to address poverty within its existing, highly constrained budget. This means it was almost impossible to implement new, targeted interventions to tackle child poverty. This is likely to continue as it is not anticipated that any significant new funding will be available to implement the new anti-poverty strategy. We also note that there is no publicly available information on public spending on the specific interventions included within the Strategy.

4.11 When we asked the Department about the budget situation, it told us that ring-fenced budgets specifically for early intervention actions might be useful. It also outlined the difficulties of implementing significant strategic plans, especially early intervention actions within the current one-year funding cycle process.

Recommendation 5

When the new anti-poverty strategy and action plan is prepared, the Department should work with contributing departments to ensure that, as far as possible, actions included are properly costed to allow the Executive to make decisions on the budget allocations required. To enhance transparency and allow an assessment of the value delivered by publicly funded services, direct spending on new actions within the strategy should be monitored and reported.

Limitations with data make it difficult to plan and assess interventions

4.12 Good quality, timely data is essential for measurement of child poverty levels, assessing the impact of strategic interventions and planning future actions. The Department produced an annual report on the progress of the Child Poverty Strategy. The report described measures taken by all departments in accordance with the Strategy and how those measures contributed to the Strategy’s aims. The most recent report, covering 2021-22, was published in October 2023 and provided data available up to the end of March 2022 for each of the strategic indicators. In the main, the information presented relates to the reporting year 2021-22. However, time lags in the data meant that some of the information was not readily available at the time of publication and so data relating to earlier years is presented. Data collection in 2020-21 was also impacted by Covid-19 restrictions and as a result child poverty statistics are not available for this year. Some of the information contained within the final report was therefore out of date by the time it was published. The impact of the continuing cost of living crisis has not been fully reflected in any poverty statistics to date and is likely to have led to worsening poverty levels in Northern Ireland.

4.13 Other publications produced by the Department include the annual NI Poverty and Income Inequality report. This is the primary source for data and information about poverty and income inequality in Northern Ireland and was last published in March 2023, based on statistics from 2021-22. Much of the reporting on poverty levels relies on the Family Resources Survey. This is an interview-based survey and typically around 2,000 households are included from a Northern Ireland total of over 768,000 households. This means that around 0.26 per cent of households are included in the survey results. Data obtained from surveys has inherent limitations, as it tends to exclude people from specific demographics and circumstances who are likely to experience the most severe levels of poverty such as the homeless population and people living in institutions.

Recommendation 6

The Department should present proposals to the Executive for monitoring mechanisms to measure the new anti-poverty strategy’s objectives and outcomes and to enable data to be collated and reported in a timely fashion.

4.14 There are concerns that single, narrow measures of child poverty are not necessarily the most useful, or aligned with what most people consider being poor. DWP has recently resumed work developing an experimental measure of poverty based on the Social Metrics Commission’s work. The Commission advocates for a new metric accounting for the negative impact on people’s weekly income of inescapable costs such as childcare and the impact that disability has on people’s needs; and includes the positive impacts of being able to access liquid assets such as savings, to alleviate immediate poverty. The Commission’s metric also included groups of people previously omitted from poverty statistics, like those who are homeless and those just above the low-income threshold but in overcrowded housing. An Experimental Statistics Senior Steering Group and Expert Advisory Group have been established by DWP to oversee the development of new experimental poverty statistics based on the Social Metric Commission’s work, and the Department is a member of both groups. First analyses and a consultation on how to improve the measure have recently been published.

Recommendation 7

The Department should continue to work closely with DWP on their work on developing a new poverty metric to enable it to determine whether a more nuanced poverty measure should be developed and implemented for Northern Ireland.

The Department has undertaken research on sources and availability of poverty data

4.15 The Department has produced a number of research reports as part of its Economic and Social Research Programme. Following a scoping review of the literature on poverty in Northern Ireland and a study of the key sources of poverty data in Northern Ireland the Department committed to examining the risk and depth of income poverty for households in Northern Ireland using administrative data (including social security benefit data and HMRC employment records). As a result, the Department has recently published the findings of a research study examining the risk and depth of income poverty for Northern Ireland households. The study concluded that the analysis presented can be used to shape interventions to assist households in or at risk of falling into poverty. It can be utilised by policy areas, for example, to find locations with a high proportion of households in poverty and address this through various outreach options. It also found that expanding upon this research would allow for the examination of additional household factors which may contribute to the number of households in Northern Ireland in poverty. We welcome these more recent reports and encourage the Department to continue its research on poverty data in Northern Ireland, ensuring the findings are made publicly available and implementing any improvements identified, particularly in the development of new anti-poverty actions in line with Recommendation 2.

Part Five: Developing an anti-poverty strategy

The NI Executive has committed to producing a new anti-poverty strategy

5.1 In line with commitments made under the New Decade, New Approach agreement in January 2020, the NI Executive agreed to the development and publication of a suite of social inclusion strategies, including an anti-poverty strategy. The Executive also agreed that a co-design approach would be used to develop the strategies, led by the Department. As a result, a number of groups were established to facilitate the co-design process.

Figure 9: The co-design process for a new anti-poverty strategy

The Anti-Poverty Expert Panel delivered its recommendations in March 2021

5.2 The Department established an Anti-Poverty Expert Panel (the Panel) in October 2020.

The Panel consisted of four members, selected on the basis of their experience and knowledge in this area. Its role was to advise the Department on strategic direction and to make recommendations on the themes, content and key actions that an anti-poverty strategy should contain. The Panel’s report was submitted to the Department in December 2020 and published in March 2021, alongside reports from the other Social Inclusion Strategies Expert Advisory Panels.

5.3 The Panel made extensive recommendations, the majority of which focus on enabling people to undertake paid work and improving social security for those who cannot work. It also recommended that the Assembly passes an Anti-Poverty Act which includes a duty to reduce child poverty, setting targets and timetables for 2030 and beyond. This would include a duty to review plans and progress against targets every five years, using 2015-16 as the baseline. The Panel also advocated for a new, non-taxable weekly Child Payment for all 0–4-year-olds and for 5–15-year-olds who receive Free School Meals, estimating that this would cost between £122 and £146 million per year.

5.4 The Department has stated that it will, in conjunction with other departments, consider the contents of the Panel’s report closely and that it will be used to inform the Executive’s consideration of the draft anti-poverty strategy.

The Anti-Poverty Co-Design Group has expressed concerns around development of an anti-poverty strategy

5.5 The Department appointed an Anti-Poverty Strategy Co-Design Group in October 2020, consisting of representatives from the community and voluntary sector, faith-based organisations, Trade Unions, and the offices of the Children’s Commissioner and the Equality Commission. The Co-Design Group was tasked with preparing a report setting out key themes and actions the anti-poverty strategy should include and the gaps in provision that it should seek to address.

5.6 The Co-Design Group understood that its role was to work alongside the Department in developing and drafting a new anti-poverty strategy, which would be evidence-based and targeted to address objective need, and in developing a supporting action plan. The Co-Design Group met throughout 2021, facilitated by the Department, providing evidence, insight and expertise, as well as sharing the views of those with lived experience of poverty.

5.7 We met with members of the Co-Design Group as part of our work on this report, many of whom shared concerns about the co-design process with us. These included that:

- Members felt there was a fundamental difference in understanding of co-design as a process between the Department and group members. Members described it as being more like engagement or pre-consultation.

- Members perceived a reluctance on the part of officials to meaningfully engage with people with a lived experience of poverty.

- At a facilitated engagement session, members told us that officials presented objectives which were mainly initiatives that could be delivered within their existing budgetary and economic constraints, rather than discussing potential new actions.

- Co-Design Group members noted the continued prevalence of silo-working in strategy development.

- Members told us they were disappointed with the absence of additional or ring-fenced budget to implement a future strategy, meaning that it will be almost impossible to develop and implement new, targeted interventions.

5.8 As a result of concerns with the process, members of the Co-Design Group approached the Communities Minister directly, and agreed to produce their own position paper, supported by Departmental officials. This paper, outlining their recommendations for an anti-poverty strategy, has been shared with the Minister and her officials and shared with the Ministerial Steering Group in April 2022. The Co-Design Group has continued to meet independently of the Department to further refine and finalise its recommendations, with the aim of wider dissemination. The paper was published in September 2022. The Department told us that the Co-Design Group’s findings will be reflected in the overall themes and vision of the

new strategy.

The Cross-Departmental Working Group no longer meets regularly

5.9 As part of the co-design approach, the Department also established a Cross-Departmental Working Group in January 2021, comprising senior representatives from across all central government departments. This group’s purpose was to support the Department to develop and draft a new anti-poverty strategy and action plan which will be outcomes-based and aligned to the Programme for Government. It was also tasked with assisting the Department in assessing the feasibility and affordability of delivering the recommendations of the Expert Panel and Co-Design Group. Officials we spoke to told us that this group had been useful and that they would not have been aware of the extent of what other departments were doing in relation to anti-poverty without it.