List of Abbreviations

CAP Climate Action Plan

CCC Committee on Climate Change

DESNZ Department for Energy Security and Net Zero

DfC Department for Communities

DfE Department for the Economy

DfI Department for Infrastructure

DAERA Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs

ESAP Energy Strategy Action Plan

ESOG Energy Strategy Oversight Group

ESPB Energy Strategy Programme Board

GHG Greenhouse Gas (Emissions)

I-SEM Integrated Single Electricity Market

LAEP Local Area Energy Plan

MSP Managing Successful Programmes

NIAUR Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulation (Utility Regulator)

NISEP Northern Ireland Sustainable Energy Programme

ONS Office for National Statistics

PfG Programme for Government

RAG rating Red-Amber-Green rating

SMR Statistical Methodology Report

ToRs Terms of Reference

UNFCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

Key Facts

2022 - Northern Ireland’s first regional climate change legislation was introduced

2022-30 - Timeframe of Northern Ireland’s Energy Strategy

£107m - Expenditure on energy-related activities since 2020

74 - Total number of actions to support/implement the Energy Strategy

1% - The percentage of the energy savings target which has been achieved

35% - The shortfall against the renewable energy target

Executive Summary

Background

1. The United Kingdom has a requirement to meet certain greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions targets, as set out in the Climate Change Act 2008 and the 2015 Paris Agreement. As a devolved nation within the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland has an obligation to contribute to the successful achievement of these targets. In that context, a climate emergency was declared by the devolved administration in Northern Ireland in February 2020 and in June 2022, the first regional climate change legislation, the Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022, received Royal Assent. It set an ambitious target of net zero emissions by 2050.

2. The context for the Climate Change Act 2008 in Northern Ireland is somewhat different from that of the other United Kingdom jurisdictions. This is due to a number of factors including the proportion of greenhouse gas emissions generated by the agricultural sector, a proportionately larger number of homes dependent on oil heating, a smaller number of homes in public ownership, and the fact that the wholesale electricity market is an all-island market (operating under European Union Internal Electricity Market rules).

3. One of the ways in which the Northern Ireland Executive responded to the legislative requirements under the Climate Change Act 2008 was through the development and publication of an Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland in December 2021 - ‘The Path to Net Zero Energy’. The Department for the Economy (‘the Department’) led the development of the Energy Strategy and is the lead department for its implementation. The Energy Strategy covers the eight-year period 2022 – 2030. The Department committed to a major strategic review of the Energy Strategy every five years, with the first to take place in 2025.

4. The Energy Group was established within the Department in 2020 to take forward the development of the Energy Strategy and its subsequent implementation. The Energy Group has 134 staff, at an annual cost of £8.2 million based on the 2023-24 financial year. It is estimated that the Department has spent approximately £107 million on this area since 2020, with almost £85 million of this being incurred on specific energy-related projects.

Key findings

The Department undertook a lengthy process and consulted widely in developing the Energy Strategy

5. The Department developed the Energy Strategy over a two-year period, liaising with relevant government bodies with responsibility for a range of areas including ‘green growth’, environment, housing and tackling poverty. A number of stakeholder groups were involved in co-design of the strategy and held discussions on issues such as decarbonising energy; the role of the consumer; energy efficiency; energy for heat, power and transport, security of supply, data, energy and the economy, and new skills and technologies. An expert panel was also established to provide advice on the methodology and policy options.

6. The Energy Strategy set a long-term vision of net zero carbon and affordable energy. In order to drive the required changes, it also set out the following three key targets:

- Energy efficiency: Deliver energy savings of 25 per cent from buildings and industry by 2030

- Renewables: Meet at least 70 per cent of electricity consumption from a diverse mix of renewable sources by 2030 (updated to 80 per cent following the introduction of the Climate Change Act NI 2022)

- Green economy: Double the size of our low carbon and renewable energy economy to a turnover of more than £2 billion by 2030

The Energy Strategy also states that it aims to reduce energy-related emissions by 56 per cent by 2030 relative to 1990 levels in line with the Committee on Climate Change (CCC)’s Carbon Budget. This was the baseline set by the Climate Change Act 2008.

There are significant flaws in the Energy Strategy Action Plans (ESAPs)

7. As part of the implementation of the Energy Strategy, the Department produces an annual Energy Strategy Action Plan (ESAP). The first ESAP was published in January 2022, with subsequent ESAPs published in 2023, 2024 and recently in 2025. However, until 2025, the actions listed in the ESAPs were not outcome focused nor were they aligned to the three key targets. Further, some objectives within the Energy Strategy had no obvious actions within the ESAPs. Due to this lack of precision, it is unclear what contribution each of the cited actions was intended to make towards the achievement of the key targets and whether all required actions were included. This has implications for the measurement of performance against planned actions. The absence of clear alignment between planned actions and the key targets contained within the Energy Strategy represents a fundamental flaw in the design of the ESAPs.

8. There were 74 actions included in the four ESAPs produced since the Energy Strategy was published. Many actions were not time-bound or precise about when the action would be completed, were sometimes unclear in terms of what work was actually planned or did not contain specific, measurable outcomes. There is evidence that some of these issues were raised by the members on the expert panel who were tasked to advise on the drafting of the Energy Strategy.

9. We identified instances where incomplete actions were not carried forward to the subsequent year’s action plan. For example, Action Eight from the 2022 ESAP was to launch a non-domestic energy efficiency scheme. The progress report published in relation to the 2022 ESAP noted that the scheme would be launched in 2023, however it was not listed as an action in the 2023 ESAP. There are other similar examples, including a case where an action was outlined in the 2022 ESAP, it did not feature on the 2023 ESAP but re-appeared on the 2024 ESAP. The Department has adjusted its approach to this and, for the first time the 2025 ESAP contained a separate table of incomplete actions from the previous year.

10. The group tasked with oversight of Energy Strategy implementation was the Energy Strategy Programme Board, subsequently renamed the Energy Strategy Oversight Group (ESOG). The above issues would indicate that insufficient attention was paid to the completeness of the annual action plans by the ESOG before their approval.

There has been limited progress on a number of planned actions

11. The first annual ESAP was launched in 2022 and some of the actions contained within it have yet to be completed. When the actions are considered in totality across all the annual action plans, there were found to be two main issues that hindered progress. The first related to the nature of the public consultation / engagement undertaken and the second was that some actions required additional work before being commenced. A tendency towards carrying out further public consultations as the action plans progressed was evident. It is recognised that public consultation is mandatory in some instances and can benefit the policy development process. However, the volume of individual public consultations across a number of the ESAPs indicates that a more strategic overview of the scope and timing of public consultations might have resulted in a reduced number of individual consultation exercises. The approach adopted may have increased the risk of reducing the effectiveness of the process, due to potential confusion and possible consultation fatigue in the groups being consulted.

12. Further, we found that some actions were not progressed because the original action was subsequently not considered feasible and additional steps were required. This would indicate that insufficient advance scrutiny of the feasibility of action points was undertaken before they were committed to, resulting in a delay being incurred in some actions. In addition, the Department advised us that in some cases a decision was taken by senior officers in individual departments not to continue to pursue the completion of an action that had previously been committed to. There is no evidence that such decisions had been approved by the ESOG, which has overall responsibility for delivering the successful implementation of the Energy Strategy.

Despite a complex governance structure, reporting on performance is lacking

13. The ESOG is responsible for monitoring and supporting Energy Strategy delivery while providing challenge and approval on issues affecting progress. The ESOG is chaired by the Head of the Energy Group within the Department, and its membership includes senior officials from the other Northern Ireland Executive departments. The ESOG is supported by the Energy Strategy Action Plan Working Group (ESAPWG), which is chaired by an official from the Department and also includes membership from the other Northern Ireland Executive departments. It has the aim of supporting coordination of initiatives and receiving updates on progress at various points of the year. In relation to monitoring delivery of the Energy Strategy, the ESOG is provided with an annual report on progress in addressing the previous year’s action plan.

14. It is important that the pace of progress in implementing the Energy Strategy and delivery against its three key targets is regularly monitored. However, the Energy Strategy does not contain any interim targets or milestones for the measurement and assessment of the pace of progress towards meeting the key targets within its eight-year term, nor have such milestones been developed. We were advised that bi-monthly progress reports are provided by ESAPWG to the ESOG and that these highlight issues that could impact the pace of progress. Without measuring progress against definitive milestones, it is difficult to effectively monitor whether the pace of progress is adequate to effect the required change within the lifespan of the Energy Strategy. It also restricts the Department’s ability to identify areas where progress is slow and to make corrective interventions on a timely basis.

The ESOG only recently measured and published progress towards the key targets

15. The Department publishes an annual report which outlines progress in implementing the actions set out in the prior year’s ESAP. The Department intended to report its progress against the metrics associated with the two pillars supporting the vision of the Energy Strategy rather than against the three key targets. Whilst data was available publicly via the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the Department to assist in measuring performance against two of the three targets, there was no evidence until September 2024 that it was used for this purpose or that performance was reported to the ESOG. Further, there was no evidence that the relevant data in relation to the third key target was available to the ESOG until the September 2024 report was issued. Without performance reporting until three years into the intended Strategy term, the Department is unable to conclude what, if any, progress against the key targets and metrics had been brought about by the actions it has undertaken, and the expenditure incurred.

16. Given that collation of the data and reporting against key targets and metrics first took place in September 2024, it was March 2025 before the Department published its progress towards achieving the three key targets and metrics contained within the Energy Strategy. The published information reflects that progress in relation to achieving the energy savings target is considerably lagging, with 90 GWh (Gigawatt-hours) of energy savings delivered against a target of 8,000 GWh. In addition, the renewable energy target is some 35 per cent short of the 80 per cent target to be achieved by 2030. The size of the low carbon and renewable energy economy was reported as £1.58 billion turnover compared to a target of £2 billion.

The advice from the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) is not considered by the ESOG

17. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) provides independent advice to the United Kingdom and devolved governments. In Northern Ireland, the lead department for corresponding with the CCC is the Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA). In this role, DAERA liaises with the other departments across the Northern Ireland Executive to prepare a response to the CCC advice. There is no statutory requirement to follow the CCC’s advice. The governance arrangements for consideration and decisions around implementation of the CCC advice are not within the remit of the ESOG. However, there was no evidence that the ESOG formally noted or discussed the energy-related CCC advice issued, or the decisions taken elsewhere about whether the recommendations in those advices would be implemented in Northern Ireland. If the CCC advice relating to energy is not subject to review by the ESOG, there is a potential risk that important recommendations are not being given adequate consideration.

Conclusions and recommendations

18. Whilst the Department consulted widely and involved a broad range of stakeholders in developing the Energy Strategy, there have been significant flaws in its subsequent implementation. The Strategy set out the Department’s long-term vision and three key targets to drive the required changes. However, annual action plans have key omissions and actions are not expressed in terms of their contribution to key targets, resulting in an inability to consider which actions were established to meet each of these targets. Monitoring of progress against some of the targets and other defined metrics took place for the first time only in September 2024, almost three years after the Strategy was published.

19. In the absence of regular monitoring and reporting against the key targets and metrics, the Department is unable to conclude what degree of progress against these has been delivered by the actions it has undertaken. It is also difficult for the Department to assess whether progress is at a sufficient pace to meet its 2030 targets. The governance and oversight arrangements around Strategy implementation did not identify these issues.

20. £107 million has been expended since 2020. This includes staff resource costs and capital investment costs related to specific projects, some of which predated the launch of the Energy Strategy. On the basis that it is not possible to assess the impact of the actions, expenditure cannot be confirmed to be an efficient use of resources and represent good value for money.

21. We welcome the recent changes made by the Department in relation to the content of the annual reports in which progress against the three key targets and metrics was published. We have made five recommendations which, if implemented, will address other deficiencies identified in the current action planning and reporting arrangements.

Recommendation 1

As part of the annual planning process, the Department should undertake a strategic assessment of the extent to which proposed actions will deliver progress against the three key targets set out in the Energy Strategy. Planned actions should detail expected outcomes and should contain specific, measurable deliverables as well as the estimated timeframe for completion.

Recommendation 2

Before the Department publishes its annual Energy Strategy Action Plan, a robust feasibility assessment of proposed actions should be undertaken, including the approach to public consultation. The public should be consulted in the most efficient and effective manner, to maximise the return from the consultation.

Recommendation 3

The Department should commission a review of the effectiveness of governance and performance reporting arrangements to ensure a sustained focus on delivery of planned actions, the achievement of key milestones and the pace of progress towards meeting the Energy Strategy key targets.

Recommendation 4

As the body responsible for strategic oversight of the Energy Strategy, the ESOG should examine all energy-related advices from the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) and ensure that the ESOG views on implementation by the Department in Northern Ireland are given appropriate consideration. All accepted CCC advice should be reflected in the annual Energy Strategy Action Plan.

Recommendation 5

The Department should carry out and publish a five-year strategic update review of the Energy Strategy in 2025 as set out in the current Energy Strategy document. Any implications arising from the introduction of the Northern Ireland Climate Change Act

in 2022 should be included within the scope of this review.

Part One: Introduction and Background

Legislative position

1.1 In February 2020, the Northern Ireland Assembly declared a climate emergency and called on the Northern Ireland Executive (‘the Executive’) to ‘fulfill its climate action and environmental commitments’. In June 2022, Northern Ireland saw its first regional climate change legislation – the Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 (‘the NI Climate Change Act’). It sets a clear statutory target of net zero emissions by 2050 and places a duty on all government departments to exercise their functions in a manner that is consistent with achieving that target as far as possible. The legislation also requires each department to monitor and report on progress made in its area of responsibility. Further implications of the NI Climate Change Act are discussed in more detail in Part Four.

1.2 Prior to the NI Climate Change Act targets being introduced, Northern Ireland already played a role in its contribution to the United Kingdom’s overall 2050 emissions reduction target and five-year carbon budgets, which were introduced through the Climate Change Act 2008. The 2015 Paris Agreement made under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) aims to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius above pre-industrial levels and the United Kingdom became the first major country to commit to a legally binding target of ‘net zero emissions’ by 2050. Northern Ireland emissions contribute to this target. The United Kingdom and devolved nations are also subject to a carbon budget. A carbon budget is the planned maximum amount of carbon dioxide emissions that can be released into the atmosphere during a set period of time. The United Kingdom’s Sixth Carbon Budget, published on 9 December 2020, included the pathway for Northern Ireland’s contribution to achieving net zero emissions. The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) within the United Kingdom Government is responsible for submitting the United Kingdom’s greenhouse gas inventory (report) to the UNFCC.

The energy sector in Northern Ireland

1.3 The power to design and implement policies in relation to energy generation, transmission, distribution and supply of electricity are devolved from the United Kingdom Government to the Northern Ireland Assembly. Other devolved matters include:

- oil and gas policy and exploration;

- coal ownership, exploitation and mining;

- production, distribution and supply of heat and cooling;

- energy conservation;

- building standards and ratings;

- energy efficiency schemes, and

- fuel poverty.

1.4 There is political commitment to addressing climate change in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland’s contribution to the statutory target of net zero carbon by 2050 is a priority referenced in the New Decade New Approach document. In addition, the Executive’s Programme for Government, (‘PfG’) ‘Our Plan: Doing What Matters Most’ published on 25 February 2025, contains the priority ‘Grow a Globally Competitive and Sustainable Economy’ and states ‘the Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland is continuing to create the right market conditions to deliver investment in our low carbon and renewable energy economy, whilst aiming to protect consumers from cost shocks, and ensuring that communities also benefit from a just transition.’

The energy sector in Northern Ireland is unique

1.5 The context for the Climate Change Act in Northern Ireland is somewhat different from that of the other United Kingdom jurisdictions. This is due to a number of factors, including, but not restricted to:

- the relative proportion of emissions in Northern Ireland generated by the agricultural sector.

- The large number of homes and businesses that are dependent on oil for heating.

- The comparatively fewer number of homes in public ownership when considered in the United Kingdom context.

- Northern Ireland is connected to the all-island Integrated Single Electricity Market (I-SEM) which is the wholesale electricity market for Ireland and Northern Ireland, a system which crosses two jurisdictions and a European Union to non-European Union boundary.

1.6 The energy sector is a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in Northern Ireland. The electricity sector accounted for approximately 14 per cent of total emissions in 2022. The domestic transport sector contributed over 18 per cent and the buildings and product uses sector over 15 per cent as shown below.

Figure 1: The energy sector is a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emmissions in Northern Ireland

Domestic Transport = 18%

Agriculture = 29%

Electricity Supply = 14%

Buildings = 15%

Industry = 10%

Land = 10%

Waste = 4%

Source: NISRA: Northern Ireland Greenhouse Gas Emissions 2022

The Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland is one part of the strategic response to legislative requirements

1.7 The requirements contained within the NI Climate Change Act are underpinned by the following strategic drivers which aim to contribute to the overall target of achieving net zero emissions by 2050:

- draft Green Growth Strategy for Northern Ireland

- draft Environment Strategy

- Environmental Improvement Plan

- Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland

- Energy Management Strategy

- draft Circular Economy Strategy

- UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

1.8 In December 2021, the Executive launched the Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland - ‘Path to Net Zero Energy’ (‘the Energy Strategy’), which superseded the Strategic Energy Framework published by the then Department for Enterprise, Trade and Investment in 2010. The Energy Strategy predated the NI Climate Change Act and set out the Executive’s long-term vision of net zero carbon and affordable energy for Northern Ireland. The lead department for the Energy Strategy is the Department for the Economy (‘the Department’) and the Energy Strategy outlined ‘[the Department] will provide leadership across the energy landscape’. Some of the other strategic drivers referred to above remain in draft form. The Energy Strategy covers the nine-year period 2021 – 2030. The Department committed to a major strategic update review of the Strategy every five years, with the first to take place in 2025.

1.9 The Energy Strategy identifies three key targets to drive change:

- Energy efficiency: Deliver energy savings of 25 per cent from buildings and industry by 2030

- Renewables: Meet at least 70 per cent (updated to 80 per cent following the Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022) of electricity consumption from a diverse mix of renewable sources by 2030

- Green economy: Double the size of our low carbon and renewable energy economy to a turnover of more than £2 billion by 2030

The Energy Strategy also states that it aims to reduce energy-related emissions by 56 per cent by 2030 relative to 1990 levels.

Scope and Structure

1.10 This report considers the Energy Strategy and evaluates the efficiency and effectiveness of the approach taken to implement it.

- Part Two considers the design of the Energy Strategy Action Plans, progress against the actions contained within them and trends arising from the data available

- Part Three examines the governance, accountability and monitoring arrangements regarding the Energy Strategy and associated action plans, and considers their effectiveness

- Part Four looks at the impact of the NI Climate Change Act on the operation of the Energy Strategy and other issues of note

1.11 Important factors that will impact on the ultimate success of the Northern Ireland Energy Strategy are the arrangements being developed to improve Northern Ireland’s energy storage infrastructure and the role of the Great Britain to Northern Ireland electricity interconnector. These two aspects are not within the scope of this current study but may well be incorporated into future NIAO reviews.

1.12 Our methodology included review and analysis of both published and unpublished information held by the Department as the lead department for implementation of the Energy Strategy. We also examined official statistical publications and engaged with the Department, and other departments of the Northern Ireland Executive. We took advice from a reference partner who has experience working within the energy sector with the United Kingdom Government.

Part Two: Energy Strategy Action Plan (ESAP) design

The Energy Strategy was developed over a two-year period

2.1 The Energy Strategy exists within a complex legal and policy environment. The initiation of the project to design an Energy Strategy was commenced by the Department, however, it is recognised that responsibility for its implementation and the impact of actions arising are felt across many departments of the Northern Ireland Executive, in particular those with responsibility for ‘green growth’, environment, agriculture, housing and poverty.

2.2 The Energy Strategy was developed in conjunction with eight stakeholder groups, each with a themed focus:

- Gas Stakeholders Group

- Electricity Stakeholders Group

- Energy Strategy Government Stakeholders Group

- Heat Working Group

- Power Working Group

- Energy Efficiency Working Group

- Consumers Working Group

- Transport Working Group (established by Department for Infrastructure)

An Energy Strategy Government Stakeholders Group was established and included membership from the other nine Northern Ireland Executive departments.

2.3 The following provides a timeline of the progress towards the development of the Energy Strategy:

| Date | Progress |

|---|---|

| 17 December 2019 | Call for Evidence opened |

| 18-28 February 2020 | Call for Evidence workshops |

| 3 April 2020 | Call for Evidence closed (extended due to COVID-19 pandemic) |

| 30 June 2020 | Call for Evidence report published |

| 31 March 2021 | Options Consultation opened |

| 15-18 June 2021 | Options Consultation events |

| 2 July 2021 | Options Consultation closed |

| 16 December 2021 | Energy Strategy published |

2.4 The Call for Evidence was the first step in developing a new Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland. It sought data and evidence in relation to key issues such as decarbonisng energy, including the role of the consumer; energy efficiency; energy for heat, power and transport; security of supply; data; energy and the economy, and new skills and technologies. This stage of the process also involved thematic workshops. The Options Consultation put forward a framework as the basis for the Energy Strategy and explored a range of potential future policy options.

2.5 As part of the process in developing the Energy Strategy, a panel of experts was established to provide advice on the methodology and policy options available to the Department. The Expert Panel on the Future of Energy (‘the Expert Panel’) was chaired by the Department’s Permanent Secretary. The Expert Panel first met on 2 September 2020 and was stood down on 10 September 2021.

2.6 As outlined in Part One, the Energy Strategy contains 3 key targets:

- Energy efficiency: Deliver energy savings of 25 per cent from buildings and industry by 2030

- Renewables: Meet at least 70 per cent of electricity consumption from a diverse mix of renewable sources by 2030 (increased to 80 per cent by the NI Climate Change Act)

- Green economy: Double the size of our low carbon and renewable energy economy to a turnover of more than £2 billion by 2030

2.7 The Energy Strategy also contains what is described as an aim ‘to reduce energy-related emissions by 56% by 2030 relative to 1990 levels in line with the Climate Change Committee’s Carbon Budget’. It is noted that the carbon budget was set prior to the NI Climate Change Act coming into force and is not an Energy Strategy-specific target. It is clear that any action taken in relation to the Energy Strategy may have an impact on achieving this aim. However, for the purposes of this study, focus is on the three specific targets outlined in paragraph 2.6 above.

2.8 The Energy Strategy is underpinned by an annual Energy Strategy Action Plan (ESAP). The Department told us that the first ESAP was developed by the Energy Strategy team following the Energy Strategy Options Consultation. This was endorsed by the Energy Strategy Programme Board (ESPB), the forum responsible for challenge and approval of issues affecting the Energy Strategy. The role of the Programme Board is discussed in more detail in Part Three. The first ESAP was subsequently approved by the then Minister and published on 20 January 2022. Since then, three further ESAPs have been published, in March 2023, March 2024 (when the Northern Ireland Assembly was restored) and more recently in March 2025.

There are significant omissions in the ESAPs

2.9 Our analysis of the published ESAPs found that many of the actions listed were not time-bound, in that they did not state a specific timeframe by which they would be completed, beyond the ESAPs generally stating that the actions listed would be ‘taken forward’ during that particular year. The Department said that the annual action plan is not a comprehensive workplan for the delivery of the Energy Strategy, but a ‘shop window’ for the public and stakeholders on some key elements of delivery in each year and that it was always anticipated that ‘not all targets would be completed within the first calendar year’. The minutes of the ESPB meeting on 14 December 2021 indicate that a potential concern was identified by members that the action plan only identifies actions for completion within 2022/23. Further, an action point emerged that SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Timebound) targets were to be considered for measurement against actions. However, the evidence from the first and subsequent ESAPs is that that this was not adequately addressed.

2.10 In relation to the principle ‘do more with less’, the Energy Strategy states the following objectives linked to this include:

- Deliver energy savings of 25 per cent from buildings and industry by 2030

- Ensure all new buildings are net zero ready by 2026/27 (earlier if practicable)

- Reduce the distance people travel in private vehicles

2.11 The Energy Strategy also states ‘we may have to retrofit approximately 50,000 buildings each year – around three times the current level – with an increased whole building approach to retrofit’. This assertion followed research commissioned by the Department in October 2020. The importance of a focus on retrofitting is also something that has been raised by the CCC in its advice. However, there was no correlating target found within the ESAPs in relation to a target number of buildings for retrofitting. Target-driven actions, which took account of the expertise commissioned, ought to have been a feature of the ESAPs in order to fully implement the Energy Strategy. Similarly, despite setting out an intention to reduce travel distances in private vehicles, no corresponding action is contained within the ESAPs to implement this, nor is there any reference to other departmental strategies that may deal with this. The recent NIAO study, ‘Managing the Schools’ Estate’, published in November 2024, highlighted that new schools continue to be built that are not net zero ready.

Actions in the ESAPs are not aligned to the key targets in the Energy Strategy

2.12 Across the four ESAPs which have been published to date, there were 74 actions in total. However, the actions were not aligned to the three key targets contained within the Energy Strategy. It is therefore unclear what contribution, if any, each of the actions will make towards the achievement of the key targets. The absence of a clear alignment between the planned actions and the targets contained within the Energy Strategy represents a fundamental flaw in the design of the ESAPs.

Some actions are inconsistently cited and lack precision

2.13 The first ESAP (2022) contained 22 activities, with each having text contained under the headings ‘action’ and ‘detail of action’. This format is repeated in the subsequent ESAPs. The Department said that the ‘action’ is the workstream target for a particular policy and the ‘detail of action’ provides further information and context on what will be progressed and the outcome, so that the reader can further understand the work to be undertaken. In some instances, we found inconsistencies in this approach. For example in relation to Action Ten in the 2022 ESAP, the action stated is ‘establish minimum energy efficiency standards in the domestic private rented sector’. The ‘detail of action’ is ‘construct and deliver a plan in 2022 to take this forward’. This appears to outline what the Department intends to do, that is, deliver a plan to bring forward new standards, not actually establish new standards. In contrast, Action Four in the same ESAP states ‘deliver £10m of funding through a new Green Innovation Challenge Fund’ and ‘detail of action’ states ‘the fund will support green technology innovation to support the growth of the low carbon and renewable energy economy’. This simply outlines the purpose of the action and reflects a lack of clarity about how the action will be taken forward. The inconsistency in citing actions has implications when it comes to the Department providing updates on the progress achieved.

Recommendation 1

As part of the annual planning process, the Department should undertake a strategic assessment of the extent to which proposed actions will deliver progress against the three key targets set out in the Energy Strategy. Planned actions should detail expected outcomes and should contain specific, measurable deliverables as well as the estimated timeframe for completion.

There has been limited progress on a number of planned actions

2.14 As previously stated, the first ESAP was launched in 2022 and the Department said that it was not intended that all actions would be completed in the first year. The monitoring of the performance of the Department against these actions is discussed in more detail in Part Three. However, some of the actions contained within the first ESAP have yet to be realised. Where limited progress against actions was noted, two of the main reasons were: further public consultation or engagement having been carried out, and the actions required further work.

2.15 The Department stated that the purpose of the ESAPs was to detail policies to be developed over the forthcoming year and that consultation is a fundamental part of policymaking, therefore it was aware that further public consultation may be necessary. We consider that it ought to have been made clear in the first and subsequent ESAPs in each instance if, and when the Department anticipated that further public consultation was required, as was the case in respect of Action 12 of the first ESAP (‘consult on a renewable electricity support scheme in 2022 for delivery in 2023’).

2.16 The Department told us that formal consultation is often a recommended part of the policy process. NICS Effective Policy Making (published in June 2007) sets out when and how it is advised to consult in the policy development cycle. Section 5.2 of the document states:

‘A formal consultation exercise is required:

- On matters to which the statutory duties (equality) are likely to be relevant;

- On equality schemes;

- On the impact of policies.

Formal consultation should be undertaken at least once during the development of the policy. However, formal consultation is also required with regard to proposals for legislation, even where consultation has previously been undertaken on the associated policy area.’

The NICS Guide to Making Policy that Works (published May 2023) states ‘if it is not clear how you are going to implement your action plan, there must be a problem with the action plan; an action plan, by definition, sets out what you and your partners are going to do.’

Set out below is a short case study. It gives a summary of the detail included in ESAPs and the subsequent reporting on them in relation to the action to set up a ‘one stop shop’ service that would provide information, advice and support to consumers on energy decarbonisation issues:

‘One Stop Shop’

Action One in the 2022 ESAP - ‘Produce a detailed plan with timescales for establishment of a one stop shop for energy information advice and support schemed delivery’.

Annual report on 2022 ESAP - ‘The Department published the Consultation on Policy Options for the Energy One Stop Shop Implementation Plan on 27 October [2022]’.

Action One in the 2023 ESAP – ‘Launch the Energy Decarbonisation Information, Advice and Support Service to Consumers’. The detail of action also added ‘we will finalise a multi-year Implementation Plan for the service reflecting the outcome of the One Stop Shop consultation’. As part of the study, the Department was asked to provide the outcome report on the public consultation it carried out. The Department responded that the consultation response will be completed and issued when the workstream is resourced and resumed. Therefore, we are unable to reflect how many responses were received and are influencing this decision.

Annual Report on 2023 ESAP – ‘Consultation closed in early 2023 and identified provision in a number of areas. Respondents indicated the need for the One Stop Shop to be linked to a financial support mechanism related to the advice given. Decision taken that progress on the One Stop Shop should be deferred and linked to the delivery of domestic energy efficiency, low carbon heat and other support schemes’. There is no reference to the One Stop Shop in the 2024 ESAP.

2.17 Public consultation is an important and valuable aspect of how Departments develop policies and strategies to help improve outcomes for people and is mandatory in certain circumstances, for example when new legislation is proposed. In developing the Energy Strategy, the Department carried out extensive public consultation and in subsequent ESAPs public consultation was a common feature of planned actions. For example, in the 2024 ESAP, 11 of the 21 actions involved some form of public consultation/engagement or a commitment to publish the outcome of same. In three of the public consultations, less than 55 responses were received by the Department. The volume of individual public consultations across the ESAPs indicates that a more strategic overview of the scope and timing of public consultations might have resulted in a reduced number of individual consultation exercises. The approach adopted increased the risk of the process being ineffective, due to potential confusion and possible consultation fatigue in the groups being consulted.

2.18 A number of the actions listed in the first ESAP were not progressed as the action was not considered feasible and additional steps were required. An example of this is in Action Seven, ‘launch a domestic energy efficiency scheme’. The Department stated that this was intended to be a pilot scheme which later ‘was not feasible to be delivered in 2022’. The Department told us that the first ESAP was discussed and reviewed at the ESPB and feasibility of the action points was subject to very senior scrutiny in advance of publication. The minutes of the ESPB did not indicate that there was scrutiny in relation to subsequent ESAP actions. The Department said that senior officials from the specific department which contributes the action are responsible for assessing feasibility as part of their policy development and delivery process. In circumstances where action points have been distilled following input from a wide range of sources, it is important that prior to committing to an action, its feasibility is examined and is supported by evidence. The ESPB as the oversight body for the Energy Strategy implementation ought to have taken a more active role in ensuring the feasibility of actions and the approach to public consultation before approving the annual action plans for publication. The role of the ESPB is explored in more detail in Part Three.

Recommendation 2

Before the Department publishes its Energy Strategy Action Plan, a robust feasibility assessment of proposed actions should be undertaken, including the approach to public consultation. The public should be consulted in the most efficient and effective manner to maximise the return from the consultation process.

There were weaknesses in the action planning process

2.19 We note that the Energy Strategy states ‘to support the longer-term phase out of gas we are already taking the necessary steps to facilitate injection of biomethane into the gas network by mid-2022’. The Department told us that biomethane was injected into the gas grid on 16 November 2023. However, there were no correlating actions relating to this work contained within the Energy Strategy prior to 2025. Following a Call for Evidence exercise in 2024, the actions within the 2025 ESAP include progressing support mechanisms, consulting on options for gas network connection costs and investigating standards/certifications. This highlights a weakness in the action planning process as well as a disconnect between the Energy Strategy and the action plans developed to deliver it.

2.20 Domestic transport accounts for 18 per cent of GHG emissions in Northern Ireland and electricity supply 14 per cent. Having reflected on the work being progressed in other jurisdictions, the absence of actions in the Northern Ireland ESAPs in relation to increasing the use of electric vehicles and encouraging an uptake on the installation of heat pumps as a source of energy in homes and businesses were noted. The importance of low carbon heating measures is reflected in the CCC reporting which combines such measures with energy efficiency measures and is given priority in the energy-related strategies of other jurisdictions. For example, in Wales, the Heat Strategy sits at the heart of its response to achieving its net zero commitment. We note that targeting the installation of heat pumps is being prioritized in Belfast at local government level. This is discussed in more detail in Part Four. The Department advised that some of the measures described would have the effect of lowering emissions in some sectors (buildings and transport) and increasing emissions in electricity sector and there is a balance to be achieved in any measures introduced.

Part Three: Governance, monitoring and reporting

Governance

Since 2020, the Department has spent over £107 million on the Energy Strategy and related initiatives

3.1 The Energy Group within the Department was established in 2020 to oversee the final stages of the draft Energy Strategy and its subsequent implementation. The Energy Group currently has 134 members of staff in post, with the majority of those individuals working on Energy Strategy implementation. The Department told us that some staff are also working on operational and legacy policy work areas. The staff resource expenditure for the Energy Group in 2023-24 was £8.2 million. In addition to staffing costs, the Department told us that to date, almost £85 million has been spent on capital projects related to the Energy Strategy, including expenditure on the following projects:

- Northern Ireland Sustainable Energy Programme (NISEP) – £3.5 million

- Energy and Resource Efficiency Programme for Businesses – £0.86 million

- Invest to Save Fund – £73 million (the Invest to Save Fund predated the Energy Strategy launch)

- Green Innovation Challenge Fund – £4.5 million

- GeoEnergy NI Project (geothermal energy) – £3 million

The governance arrangements relating to the Energy Strategy are complex

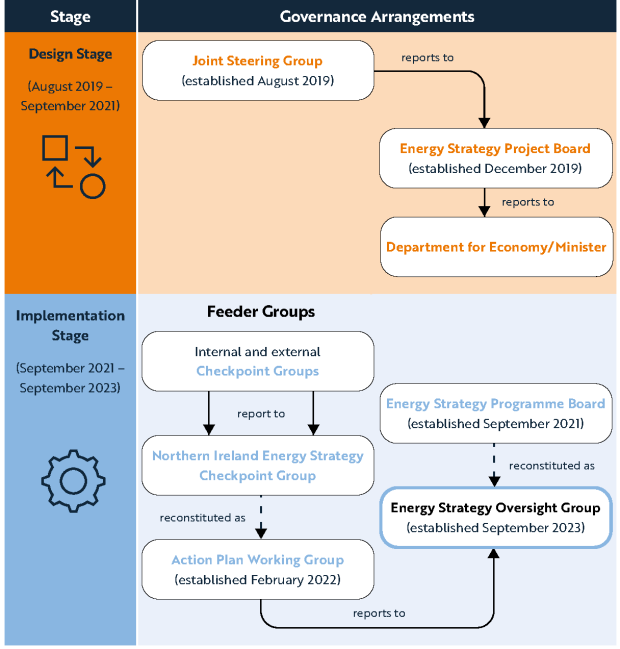

3.2 The governance arrangements for the Energy Strategy are summarised in Figure 2. At the inception stages of the Energy Strategy, an Energy Strategy Project Board (‘the Project Board’) was formed to oversee and direct the development of the draft Energy Strategy. The Terms of Reference (‘ToR’) of the Project Board outlined the ambition to provide a draft Energy Strategy by December 2020 for approval by the Departmental Board. The Project Board comprised senior officials from the Department, Northern Ireland Authority for Utility Regulation (‘Utility Regulator’) and the Consumer Council for Northern Ireland. It first met on 2 December 2019 and was chaired by the Department’s Permanent Secretary.

3.3 A Departmental/Utility Regulator Joint Steering Group (‘the Joint Steering Group’) was established to ‘deal’ with the Department’s approach to developing an Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland. The Joint Steering Group’s Terms of Reference (ToR) state its objective was to ‘oversee, guide and develop the new draft Energy Strategy for consideration by the Project Board’. The ToR also states that the two parties will ‘work collaboratively through the Joint Steering Group to provide substantive material to the Project Board’. The Joint Steering Group first met on 8 August 2019 and was stood down following a meeting on 20 August 2020 when it was deemed to have fulfilled its role in producing the Call for Evidence in relation to the Energy Strategy.

3.4 In September 2021, the Energy Strategy Programme Board (ESPB) was established. This replaced the Project Board and was chaired by the head of the Energy Group within the Department. The ToR of this group state that its objective was to ‘monitor and support the delivery of the new Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland and support the Senior Responsible Owner to make decisions while providing both challenge and approval on issues affecting the progress of the programme’. Membership of the ESPB included officials from the other Northern Ireland Executive departments. The ESPB continued to meet following the publication of the Energy Strategy and was reconstituted to the Energy Strategy Oversight Group (ESOG) with unchanged membership in September 2023. The Department told us that this was due to governance moving from an MSP Programme model (Managing Successful Programmes – a methodology that comprises a set of principles and processes for use when managing a programme) to a strategic planning and reporting model with the delivery of the plan managed by individual departments.

3.5 In addition, in 2022 two Energy Strategy Strategic Checkpoint Groups (one internal Departmental group and one external to other departments) were established to contribute to the delivery of the Energy Strategy and monitor progress of actions within relevant departments/organisations. The Department told us that these groups initially worked together and were later formally amalgamated, at which point the Group became known as the Energy Strategy Action Plan Working Group (ESAPWG). Its objective was to ‘monitor and support the coordinated delivery of the annual Energy Strategy Action Plan’. The ESAPWG reports to the ESOG as and when required and membership comprises individuals identified as Action Leads from departments and organisations responsible for actions.

Figure 2: Summary of Energy Strategy governance arrangements

3.6 The above demonstrates a complex and changing landscape in the governance of the Energy Strategy, involving a large number of individuals at various levels and a significant amount of work preparing for and attending meetings relating to it. Given our findings in relation to the design of the action plans, the ESPB is not deemed to have been effective in meeting its objective. However, we note that there does appear to have been a clearer focus on implementation and reporting against actions since the governance was somewhat streamlined.

Despite the complex governance, there is no published assessment of whether actions have been met

3.7 Since the first ESAP was published in 2022, there have been three annual reports issued by the Department in relation to completion of the published actions. The first one was in February 2023, which reported on the initial ESAP, the second in February 2024, which reported on the 2023 ESAP, and the third in March 2025 which reported on the 2024 ESAP. It is the Department’s practice to publish the report on the previous year alongside the action plan for the incoming year. We considered the three annual reports in detail and noted that an update is provided in relation to what steps have been taken in relation to each of the actions specified in the action plan. However, the reports do not specify if the planned action was achieved in full within that year. The Department was asked about this and said that the explanatory text in the annual report ‘demonstrates whether the action was achieved or not achieved’. However, our assessment is that it is not always clear if the action was fully achieved nor is it always clear exactly what remains outstanding.

There is little correlation between action plans, and there is a lack of follow-up on incomplete actions

3.8 In our analysis of the annual reports related to the ESAPs, we identified actions which we consider were not completed within the respective year based on the published narrative.

We found instances where an incomplete action was not carried forward to the subsequent year’s action plan, examples of which are detailed below:

Action 8 (2022 Action Plan): Launch a non-domestic energy efficiency scheme

The action plan stated that this would deliver a new energy efficiency support scheme for Northern Ireland businesses. The annual report in relation to this action stated:

A new energy efficiency support programme for businesses has not been launched in 2022.

During 2022, there has been an ongoing period of evidence gathering and stakeholder engagement through surveys, workshops, and discussions with other jurisdictions to ensure a robust evidence base for scheme design.

The new scheme will be launched in 2023 providing financial support for eligible businesses, and will be accompanied by live support including advice and technical consultancy relating to energy efficiency and decarbonisation.

Despite the narrative in the annual report, the launch of a non-domestic energy efficiency scheme was not an action within the subsequent (2023) ESAP.

Action 16 (2022 Action Plan): Develop and commence delivery of a geothermal demonstrator project

In the action plan, the ‘action’ was stated that the Department would develop and commence delivery of a geothermal demonstrator project. Under ‘detail of action’ it stated ‘undertake feasibility studies to inform future decisions on suitable locations…’ The annual report stated:

During 2022 the Department for the Economy created a business case, carried out premarket engagement and is currently in the procurement phase of feasibility studies and pre-drill activities for one deep geothermal project and one shallow geothermal project. The delivery of these projects will continue in 2023.

These projects will help inform future policy in relation to geothermal energy and help develop the appropriate frameworks for geothermal heat. The Department for the Economy will commence public engagement to improve public understanding of the technology. It is expected that the projects will also encourage private sector investment in geothermal technologies to establish them as part of a wider roll out of heat networks.

However, the development and commencement of delivery of a geothermal demonstrator project was not an action within the subsequent (2023) ESAP. The 2024 ESAP, however, included an action to publish the outcome of feasibility studies. This highlights the difficulties when monitoring progress of actions which have no published expected outcome as it is not clear if any outcome (related to the Energy Strategy itself) has been achieved.

Action 10 (2023 Action Plan): Develop a plan for decarbonisation of Rathlin Island

In the action plan, it stated that the Department for Infrastructure (‘DfI’) would develop a cohesive plan to decarbonise Rathlin Island. The annual report for 2023 stated:

Work is nearing completion with the Rathlin Development Community Association (RDCA) to produce a Rathlin Island Climate Action Plan and is expected to be finalised in early 2024. The plan will build on the findings of the recent Rathlin Carbon Audit report.

Two consultation events on the draft plan were held with the island community and other key stakeholders on 29th November and 12th December to identify and prioritise community actions for decarbonising the island.

However, the further development and/or publication of a decarbonisation plan for Rathlin Island was not an action listed in the 2024 ESAP.

3.9 In our consideration of the action plans and annual reporting, we also identified an example where the action was followed through from a previous action plan but regressed between action plans:

Action 7 (2022 Action Plan): Launch a domestic energy efficiency scheme

| Action | Detail | Owner | |

| 7 | Launch a domestic energy efficiency scheme | This will deliver an area-based enery efficiency pilot scheme in 2022. It will support investment in improved energy efficiency measures in domestic buildings and inform the roll-out of a longer-term programme. It will also include access, where relevant, to low-carbon heating support. | DfE |

In the 2022 Action Plan report, the narrative in relation to this action states:

Unfortunately, following significant engagement with stakeholders, it emerged that the delivery of a pilot domestic energy efficient scheme would not be feasible in 2022. However, it also became clear that more urgent action at a larger scale is needed across Northern Ireland.

Officials are now progressing the development of a multi-year Energy Efficiency Intervention Programme that would scale up quickly to deliver the volume of high-quality retrofits required to both meet our net zero commitments and tackle the cost-of-living crisis. We are urgently determining the appropriate levels of support and the funding required.

The action to launch a domestic energy efficiency scheme was not carried through to the 2023 ESAP, however the 2024 ESAP includes an action to publish a consultation on the future of domestic energy efficiency support and delivery. This appears to be a significant regression of the action initially stated almost three years previously. The lack of continuity from one year to the next makes it very difficult to follow actual progress being made and increases the risk that uncompleted actions could be overlooked in future planned activities.

3.10 We asked the Department what regard was given to lessons learned from the setting of prior actions, and the decision-making process behind whether an action was carried forward or discontinued. The Department informed us that senior officials from the relevant departments on the ESOG had input into the annual report in respect of the actions owned by their department and are responsible for monitoring and considering lessons learned when formulating new actions. Similarly, the Department stated that those senior officials decide whether their department’s actions should be carried forward or discontinued. This is outside the governance arrangements whereby the ESOG should approve the action plans. It is noted that the 2025 ESAP specifies five actions which were ‘rolled over’ from the 2024 ESAP and we welcome the progress in clarity this brings.

Monitoring and reporting

The Department’s focus is on updating against the two pillars of the Energy Strategy vision, rather than against its key targets

3.11 Despite the publication of three distinct key targets within the Energy Strategy, the Department’s focus is on measurement of progress against the two pillars contained within the vision: ‘net zero carbon energy’ and ‘affordable energy’. The Energy Strategy outlines more detail on this vision and how it will measure success:

| Vision | |

|---|---|

| Net zero carbon and affordable energy | |

| Net Zero Carbon Energy | Affordable Energy |

| What this means | What this means |

| Net zero carbon energy means that overall greenhouse gas emissions from energy are zero. It means reducing emissions from the energy we use for transport, electricity generation, industry and our built environment, as well as removing any remaining emissions with schemes that offset an equivalent amount from the atmosphere. | Energy provides value in enabling our comfort, leisure, and basic needs. However, affordable energy can mean different things to different groups of consumers, for example energy bills can be a major concern for households on lower incomes, or help to ensure that businesses can be competitive in challenging markets. |

| How we will measure success | How we will measure success |

We will monitor greenhouse gas emissions from energy-related sectors: • Business • Energy Supply • Industrial Process • Public • Residential • Transport | We will measure three key indicators to support our assessment of affordability: • Business • Households in fuel poverty • Business energy purchases relative to turnover |

Source: Department for the Economy, ‘The Path to Net Zero Energy’

There are a number of data sources involved

3.12 The Energy Strategy outlines that GHG emissions for energy-related sectors will be tracked to monitor progress on the ‘net zero carbon energy’ aspect. In relation to the aspect of the vision on ‘affordable energy’, the Energy Strategy identifies three ‘key metrics’ which it states will be tracked as part of the Energy Strategy: household energy expenditure relative to all expenditure; households in fuel poverty, and business energy purchases relative to turnover.

3.13 Alongside the Energy Strategy, the Department published a document entitled Energy Strategy Metrics : Statistical Methodology Report (‘the SMR’). It states that its purpose is to ‘outline current definitions, data sources and methodologies for each strategic metric that will be examined alongside the Energy Strategy for Northern Ireland’. This document also states that an additional two metrics will be used to ‘link in’ with two of the five key principles contained in the Energy Strategy. The two metrics are:

- Employment and turnover in the low carbon and renewable energy economy (linked to principle ‘Grow the green economy’)

- Relative electricity and gas prices (linked to principle ‘Replace fossil fuels with renewable energy’)

3.14 As part of the study, we asked the Department to detail the progress reporting and monitoring arrangements put in place when the Energy Strategy was launched in relation to the metrics outlined. The Department referred to three information sources:

- The Low Carbon and Renewable Energy Economy which is monitored by the Office for National Statistics (‘ONS’)

- Renewable Energy Generation and electricity consumption in Northern Ireland produced by Analytical Services Division within the Department

- Data from the subnational final energy consumption produced by the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (‘DESNZ’) within the United Kingdom Government was initially considered. However, the Department outlined that it was subsequently considered that it would be more appropriate for data on each scheme aimed at reducing energy consumption to be the source for the information on energy saved. This is further discussed below.

There is limited data available to measure progress against one of the three key targets

3.15 When the Energy Strategy was first published, a baseline figure of 32,000 GWh (Gigawatt-hours) per year was estimated for the heat and power demand in buildings and industry. This figure was derived from United Kingdom Government statistics and used an average over the years 2016-2018. The Department initially intended to use these statistics to track progress, however a decision was taken at the ESOG in 2024 to discontinue the use of this data to monitor energy savings. The reason cited for this decision is that, due to the methodology deployed in publishing the statistics, which included retrospectively amending historical data, energy savings gained may be ‘masked’ by growth in consumption due to population or economic growth. However, we found no evidence that the Department used this data to track or measure progress, even prior to this decision being taken. The Department told us that this was due to the lag time in the data being published. The decision was taken that as an alternative, the source of information on energy savings should be from the contribution of individual government funded schemes. The original baseline of 32,000 GWh was retained. As outlined above, the target was initially expressed as a 25 per cent reduction in energy consumed but is now expressed in GWh (8,000) rather than a percentage. The Department stated this approach is consistent with activities detailed in the draft Climate Action Plan, which was issued for public consultation on 19 June 2025. The Department accepts that it is dependent on the data being published by the relevant government owner, and there are time lags of 18 to 24 months associated with this data. As a result, despite being four years into the Strategy term, there is extremely limited data available in relation to one of the three targets.

The ESOG only recently measured and published progress towards the key targets in the Energy Strategy

3.16 Despite the level of detail in the documents setting out what the Department intended to measure alongside the Energy Strategy, and the changes in what data was intended to be tracked, this study was unable to uncover evidence of any published report by the Department that showed performance against any of the metrics or targets it had committed to until September 2024, almost three years into the Energy Strategy term. At that point, the ESOG was presented with an Energy Strategy Targets and Metrics paper, which collated the published statistics from multiple sources as outlined above. Importantly, it assessed how this compared against the key targets and metrics that had been set. Prior to this, data in relation to renewable energy production and estimated turnover in the low carbon and renewable energy economy, published by the Department and ONS respectively, was directly available and could have been used by the ESOG to measure and report performance against the targets. However, there is no evidence that it was used for this purpose. Without clear, published tracking of performance against targets, there was a clear gap in the process between strategy development and implementation, leaving the Department unable to conclude what, if any, progress against the key targets and metrics was being brought about by the actions undertaken and the expenditure incurred. The Department states that it intends to update the paper as future data is published.

There was no consideration given to monitoring the pace of progress being made

3.17 Our work revealed that the Energy Strategy did not contain any milestones for the measurement and assessment of the pace of progress towards meeting the three key targets within its eight-year lifetime. The Department told us that pace of progress is reported on through policy leads from across departments at the ESAPWG, that each policy lead is required to produce a bi-monthly progress update indicating Red-Amber-Green (RAG) rating and any issues with risks, including those that will impact pace of progress. The Department added that progress updates are provided to the ESOG, whose members ‘consider and provide strategic leadership across departments to address issues impacting pace of progress’. However, it is noted that monitoring of the pace of progress towards the Energy Strategy key targets is not contained within the ToRs of the ESAPWG and its role is considered to be less strategic, providing operational updates on actions and a co-ordination function. We also consider that without regular monitoring of the relevant data, including the effective use of milestones, it is difficult to ascertain the pace of progress.

3.18 It is noted that the pace of progress towards the net zero targets is something that has

been raised by the CCC in its advice report on Northern Ireland’s Fourth Carbon Budget

in March 2025.

Publication of performance against the targets contained within the Energy Strategy only recently commenced

3.19 The Department’s published annual reports provided an update on actions which were listed in the respective ESAPs. However, before the annual report published in March 2025, the Department did not publish progress towards achieving the three key Energy Strategy targets in its annual reporting. As a reminder, the Energy Strategy set out the following three key targets:

- Energy efficiency: Deliver energy savings of 25 per cent from buildings and industry

by 2030 - Renewables: Meet at least 70 per cent of electricity consumption from a diverse mix of renewable sources by 2030 (amended to 80 per cent by Climate Change Act (NI) 2022).

- Green economy: Double the size of our low carbon and renewable energy economy to a turnover of more than £2 billion by 2030

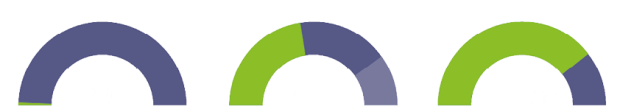

3.20 The chart below is an extract from the most recent Annual Report in March 2025 and shows the published performance against the three targets:

Overview of Targets – Current position against target

Source: DfE Energy Strategy Action Plan 2024 Report

3.21 The chart demonstrates the progress towards the three targets as published in the Energy Strategy Targets and Metrics paper that was presented to the ESOG in September 2024. The recent development in reporting progress towards the three targets is welcomed. This reflects the extent of the lack of progress in relation to delivering the energy savings target, having achieved just over one per cent of its target to date. We consider that regularly and openly tracking progress towards the key targets by those tasked with oversight is a critical aspect of effective policy implementation.

3.22 Due to the lack of specific reporting on progress against these targets, there was no information published by the Department to inform external stakeholders regarding the Department’s performance in this area. Therefore, information was not readily available to enable stakeholders to form an assessment of the effectiveness of the measures taken to date in contributing positively to the targets.

Recommendation 3

The Department should commission a review of the effectiveness of governance and performance reporting arrangements to ensure a sustained focus on delivery of planned actions, the achievement of key milestones and the pace of progress towards meeting the Energy Strategy key targets.

Future challenges

Legislative changes have shifted the focus

4.1 As referred to in Part One, the Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 (‘the NI Climate Change Act’) brought about significant legislative change in this area. It received Royal Assent on 6 June 2022, approximately six months after the publication of the Energy Strategy. It sets an overall target of 100 per cent reduction in net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and an interim target of 48 per cent reduction by 2030. The NI Climate Change Act places a legal requirement on all Northern Ireland departments to exercise their functions, in so far as is possible, in a manner consistent with the achievement of the targets contained within it.

4.2 The Climate Change Act includes several important provisions related to energy:

- Sectoral Plans (Section 14): requires the Department to develop and publish a sectoral plan for the energy sector, setting out how the sector will contribute to the achievement of the 2030, 2040 and 2050 carbon reduction targets contained within the legislation. Sectoral plans for energy must include proposals and policies for energy production and the supply for private and public heating and cooling systems.

- Renewable Energy Targets (Section 15): sets a target for at least 80 per cent of electricity consumption in Northern Ireland to come from renewable sources by 2030. This target supersedes the renewable electricity target contained within the Energy Strategy.

- Carbon Budgets (Section 23): requires DAERA to set carbon budgets, which are the maximum total amount of greenhouse gas emissions permitted for specific five yearly periods. These budgets must align with the overall emissions reduction targets, of 2030, 2040 and 2050.

- Climate Action Plan (Section 51): the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) is required to produce a five-year Climate Action Plan (CAP) to set out the policies and proposals that Northern Ireland departments will implement to meet the corresponding carbon budget requirements and how the emissions reduction targets will be achieved. The NI Climate Change Act stated that this must be done within 24 months of the legislation receiving Royal Assent (6 June 2024). In addition, Section 29(7) of the NI Climate Change Act states that this must be completed by the end of the first year of the carbon budget period (31 December 2023). A Climate Action Plan for Northern Ireland has not yet been produced.

4.3 The Department told us that representatives on the ESOG are responsible for aligning their Energy Strategy input with the requirements set out in the NI Climate Change Act. It also said that all departments support DAERA in developing the CAP by putting forward policies and proposals that are consistent with achieving the targets within the carbon budget period. The Department established a Climate Change Oversight Group to provide governance in the exercising of its own functions.

4.4 The Department is of the view that the NI Climate Change Act has been very helpful in dealing with the difficulties around data to support energy savings measures. Work has been taken forward to align the monitoring of the energy savings target with those policies and proposals which were put forward across the Northern Ireland Executive in relation to the emissions reduction pathway. We note that, to date, the energy sectoral plan has not been published. The Department stated it is concentrating on its contribution to the CAP ‘as an immediate priority…we will then focus on the sector plan which will include input from other departments’. It is positive that the passing of the NI Climate Change Act in 2022 appears to have incentivised efforts around reporting and monitoring and the input of other departments. We await with anticipation the launch of the CAP and encourage all departments involved to act expeditiously in their efforts to progress this.

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC)

4.5 The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) was established in 2008 to provide independent advice to the United Kingdom and devolved governments on setting and meeting carbon budgets and preparing for climate change. The CCC’s role with respect to Northern Ireland involves advising on carbon budgets, publishing regular progress reports (with the first progress report due to be published before the end of 2027), and advising on adaptation strategies to assist the Northern Ireland Executive.

4.6 In Northern Ireland, the Climate Change Act refers to statutory interactions between the CCC and DAERA as the lead department. The NI Climate Change Act requires DAERA to prepare a response to the points raised by each progress report of the CCC within six months of receipt, and all departments of the Northern Ireland Executive are required to provide assistance to DAERA in the preparation of these progress responses. As part of the study, we engaged with officials from DAERA who outlined to us the process involved in responding to the CCC’s progress reports. Officials outlined that an advance copy of progress reports is shared at ministerial level between DESNZ and DAERA, following which DAERA shares the report with the other departments of the Northern Ireland Executive. Officials advised that recommendations of the CCC are advisory, there is no follow-up on recommendations and advice, and if recommendations are not followed, they will be repeated in the subsequent CCC report or advisory note. Officials informed us that actions are carried through the departmental structures. However, we found no evidence to support this in the Departmental Board or Audit and Risk Committee minutes or reflected in the ESAP plans published after the advice or recommendations were received.

4.7 The Department told us that the CCC’s advice to Northern Ireland was considered by DAERA during the legislative process of setting the first three carbon budgets, and the 2040 and 2050 greenhouse gas emissions targets. Following public consultation, the carbon budgets were passed into law in 2024. The Department also said that CCC advice on carbon budgets, broken down to a sectoral level, has been used to ensure individual sectors meet their respective carbon budget. It is positive to see that the CCC’s high level advice in relation to the direction of travel is utilised. However, we did not find evidence that the CCC’s specific advice was taken into account at a strategic level when considered in the context of the energy sector. An example of this is outlined in the paragraphs that follow.

The CCC advised that actions should be accelerated

4.8 In the letter from the CCC Chairman on 25 March 2022 (referred to above), specific elements of policy and the implications of the net zero target were highlighted. The following extract is relevant to the energy sector:

‘It may be instructive to consider the implications of our previous advice. These might now be considered minimum requirements under the new legislation.

- Energy generation. Deployment of renewable energy generation is required at scale, with appropriate energy storage and decarbonised back-up solutions (e.g. gas turbines burning hydrogen manufactured from low carbon sources) to allow the carbon-intensity of electricity generation across the Irish electricity system to fall to around 50gCO2 /kWh by 2030, on the way to fully phasing out unabated fossil-fired generation by 2035. Demand for electricity will grow, perhaps doubling by 2050, given the crucial role of electrification to replace fossil fuels. Production or imports of hydrogen from low carbon sources will also be important, for use in industry, electricity generation and more widely.’

4.9 In our engagement with DAERA officials, we attempted to ascertain how this clear advice to escalate progress in relation to renewable electricity generation was actioned. DAERA officials advised that as the energy sector lead, the Department for the Economy has responsibility. However, the Department referred us to the energy production sector stakeholder consultation, that was ongoing as part of the Climate Action Plan. Our work did not find evidence of weight being given to the CCC’s sectoral specific advice in relation to the energy sector either by the ESOG or the Department. There was no evidence of a focus on escalation or urgency of activities in the way that CCC outlined.

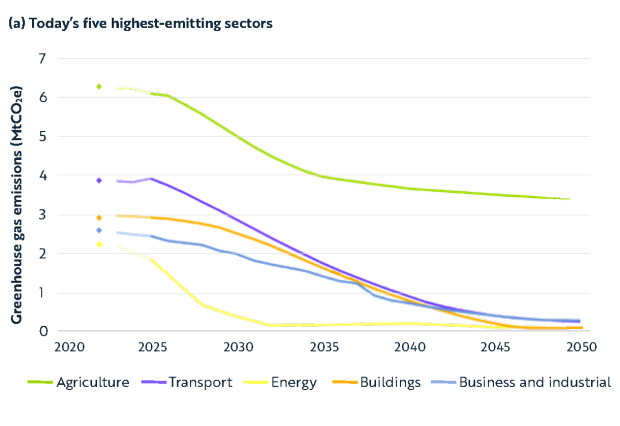

4.10 The most recent advice on the fourth carbon budget for Northern Ireland was published on 19 March 2025. The Department told us that officials from the Energy team have met with the CCC since its publication, to understand the assumptions behind the modelling outlined in the report. In the advice, the CCC comments that ‘the pace of emissions reduction [in Northern Ireland] will need to significantly increase to achieve the first three carbon budgets…’ The advice provided a breakdown of the current and budgeted emissions per sector:

Recommendation 4

As the body responsible for strategic oversight of the Energy Strategy, the ESOG should examine all energy-related advices from the Climate Change Committee (CCC) and ensure that the ESOG views on implementation by the Department in Northern Ireland are given appropriate consideration. All accepted CCC advice should be reflected in the annual Energy Strategy Action Plan.

Belfast City Council has published its own Local Area Energy Plan